As Nelson Algren wrote in the opening lines of The Man with the Golden Arm, we’re in “that smoke-colored season between Indian summer and December’s first true snow,” a season of “leaden…twilight.” It’s the best description of late autumn in Chicago ever committed to paper, maybe the best description of Chicago weather at any time of year. That makes this a good time to talk about Algren — specifically, why we’re still talking about Algren.

I’ve been a Nelson Algren fan ever since I discovered a pulp paperback copy of A Walk on the Wild Side on a carousel in my high school English class. The lurid comic tale of an illiterate Texas drifter who ends up starring in sex shows at a New Orleans brothel was not the usual earnest American literature fare — which may be why I enjoyed it so much.

In 1989, eight years after Algren’s death, Bettina Drew published Nelson Algren: A Life on the Wild Side, which made Algren out to be as much of a sad sack as the down-and-out characters in his fiction: washed up as a writer at 40, hustled out of his material by Hollywood, unable to keep a wife, shunned by publishers, broke from gambling away his money in poker games and at the track or spending it in bars and brothels. A briefly brilliant career followed by a long, bitter decline to a seedy end. In one anecdote, a 67-year-old Algren is running for a train after winning $236 at a New York City racetrack. He’s wearing the only pair of pants that fits over his belly, but has to hold them up so they don’t fall around his ankles, because they won’t zip: “I hold them together with a horse-sized safety pin and wear my shirt outside to cover the pin.”

For nearly 30 years, that was the only Algren biography. Did we need another? While Algren is revered in Chicago — the Chicago Tribune named its short story prize after him, and there’s a fountain dedicated to Algren in Wicker Park where he lived and set many of his stories — but he’s not a canonical author like his contemporaries Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, and William Faulkner, or his local contemporary Saul Bellow, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Even during his lifetime, he was considered out of fashion, a writer whose sensibilities were shaped by his days riding trains during the Great Depression, and who persisted in writing about the noir worlds of drug addicts, prostitutes, and thieves even during the prosperous years of post-World War II America. “The bard of the stumblebum,” mocked critic Leslie Fielder. “The Last of the Proletarian Writers.”

Yet in recent years we’ve gotten two more Algren biographies: Algren, by former Tribune reporter Mary Wisniewski, published in 2017, and Never A Lovely So Real, by Colin Asher, published by 2019. (Asher’s title comes from Algren’s assessment of Chicago in Chicago: City on the Make — “Loving Chicago is like loving a woman with a broken nose. There may be lovelier lovelies, but never a lovely so real.”) Both are more flattering to Algren’s life and work than Drew’s book. Why so much continuing attention to an author once dismissed as a period piece of local interest only?

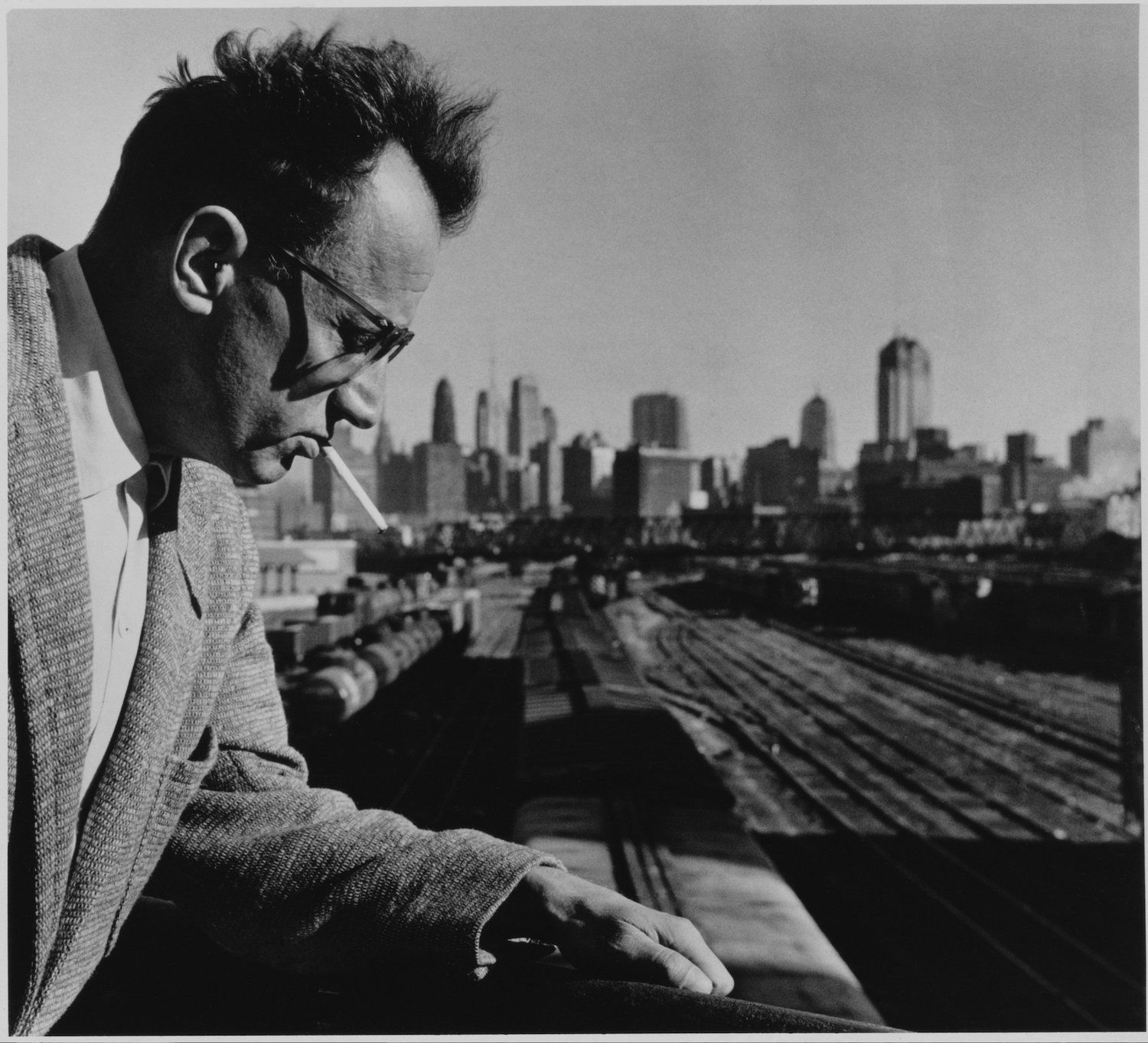

A couple reasons. First, writers love writing about Algren because Algren was a writer’s writer, never allowing money, love, status, or comfort to distract him from the pursuit of his art. After coming home from World War II, he could have bought a comfortable house with GI Bill money. Instead, he stayed close to his material by living in a flat on Wabansia Avenue, with, Winsiewski writes, “a desk with a typewriter and a reading lamp, piles of typed paper, and a record player.” (This was where he began his famous affair with French author Simone de Beauvoir.) Kurt Vonnegut, who taught with Algren at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, once said that his “enthusiasm for writing, reading and gambling left little time for the duties of a married man.”

Another reason is that while Algren’s reputation went into eclipse during the middle class moment of mid-century America, his work once again seems timely as the underclass he wrote about has re-emerged. The Man with the Golden Arm, whose main character is a morphine-addicted card dealer, was self-consciously behind the times. Set in the 1940s, its characters remain trapped in Chicago’s decaying ethnic ghettos while all their smart neighbors move to the suburbs. Frankie Machine and his sidekick Sparrow “had merely emerged from the wrong side of the billboards.” On the other hand, the book was unconsciously ahead of the times, anticipating the drug culture of the 1960s, and the enormous wealth inequalities of the 21st century.

“Today,” writes Asher, “the book doesn’t seem outre — it seems prescient…By the time Nelson began writing Arm, he had realized that the lives lived by people surviving at the margins of society provided a glimpse of the future.”

(Asher’s book also challenges the notion of Algren as a starving artist. He sold the paperback rights to Arm for $25,000 — equivalent to $286,000 today. Algren was never wealthy, but he never had to work for The Man, and he had the time and money to accompany Beauvoir to Mexico and France. Living most of his life as a childless bachelor helped, no doubt.)

If there was a tragic aspect to Algren’s life, it was that he peaked as an artist at the worst possible moment for his art: just before the middle-class conformity and the Red Scare of the 1950s. (The FBI investigated Algren on suspicion that he was a communist, which Asher believes contributed to the diminishment of his literary output.) Algren may not have been a writer for those times, but he’s a writer for ours.