ABC’s six-episode series, Women of the Movement, explores the events surrounding 14-year-old Emmett Till’s death from the perspective of his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley. Till, a Black boy from Chicago, was brutally murdered in 1955 in Mississippi — and his death would help ignite the Civil Rights movement.

Women of the Movement was created by Marissa Jo Cerar, who worked on The Handmaid’s Tale, and was co-produced by Jay-Z and Will Smith. Viewers watch Mamie decide to open her son’s casket to the public, testify at his murder trial before an all-white Mississippi jury, and her journey into activism.

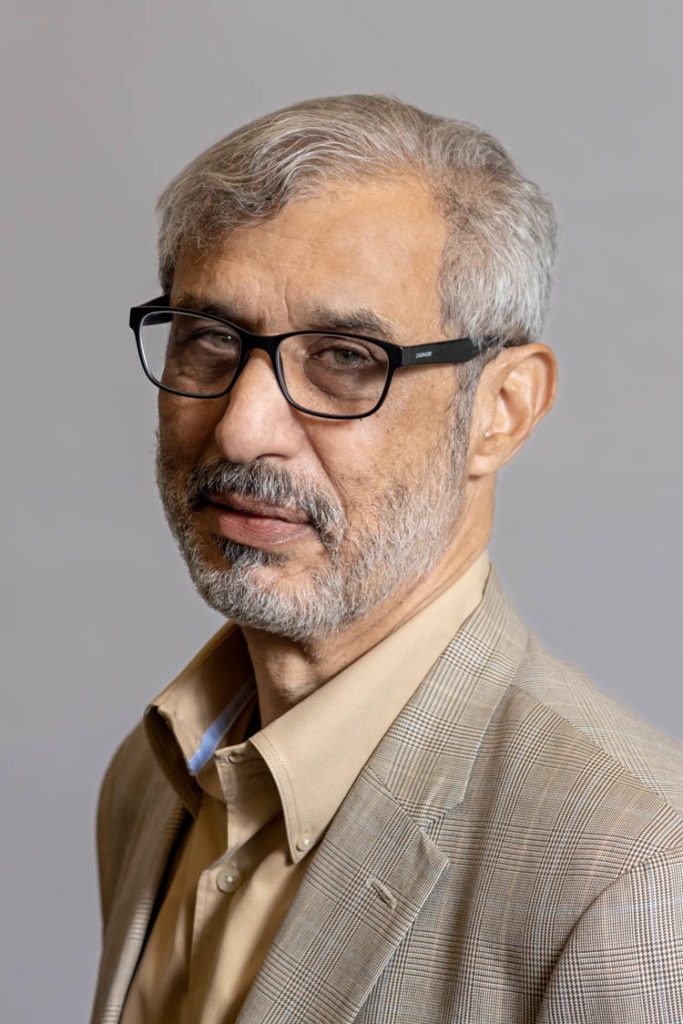

The series is based on the book Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America, which Till-Mobley co-authored with Northwestern University journalism professor and author Christopher Benson before she died in 2003. Benson worked as a consultant on the show, which first aired on the anniversary of Till-Mobley’s death on Jan. 6, 2022. Benson is now writing a new book with Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr. — Emmett’s cousin — about the FBI’s investigation into Emmett’s murder.

Benson spoke to Chicago magazine about writing a book with Till-Mobley, the show’s portrayal of events in their book, and Till-Mobley’s monumental decision to let people see her son’s body after his murder.

How did you come to co-author Death of Innocence?

I met Mamie Till-Mobley in June 2002. Some mutual friends of mine brought me into conversation with her because they were planning to develop a motion picture based on the Emmett Till story. They knew that I was a writer of long-form narrative, and they wanted me to be in the conversation. She found out I wrote a novel, and then suddenly, the conversation shifted. She said, “I always wanted to write a book.” When we left, I said to my friends that I would pitch the book idea to my agent. And we could use the book as a platform to do the motion picture or TV series, or whatever it was going to develop.

It’s interesting because I was about to get started on my second novel. And I decided — basically in a split second — that this would be the most important project I could undertake. I could easily have said to Mamie Till-Mobley that I’ll get back to her in about six months after I finished the other book. As it turned out, this was the beginning of the last six months of her life. We worked together during that period to make sure that her story would live on past her. If I had waited six months, we would have lost the story forever.

The research that I did really opened my eyes to the impact of not only journalism, but particularly Black journalism in doing what journalism was supposed to do — and that was to go after the truth.

Were there particular parts of the story that you and Mamie wrote that the producers wanted to make sure weren’t left out?

I think to their credit, they wanted to do what I had set out to do with her. And that was to present the story of Emmett Till as a story of more than an icon, a martyr in a movement, to fully humanize him and their relationship so that we feel the loss of this wonderful kid. We see it in the context that we tried to infuse the book with, to show how this was not just a random act of violence.

This was not just an act of racial violence, committed by some people in Mississippi against another person. This was part of the structure of race in our country. It was something that we talked about in the book, with respect to the pushback against the implementation of Brown v. Board of Education and a whole new way of life, if you will, for the South, for the entire country. Brown v. Board of Education marked the end of apartheid in this country. And there were people who resisted that. I think they effectively captured that theme of the book, and I think did justice to our story.

Mamie’s decision to open the casket and let people see Emmet’s body was a defining moment in the show and in real life. Where do you think her resolve came from to do that?

It was really a powerful moment. Up to this tragedy, her mother was really the strong person in their relationship. And she described her relationship with Emmett — and others have described the relationship — as more like brother and sister than mother and son, because her mother was the matriarch of the family. But then, at the point of this tragedy, her mother collapsed emotionally and was no longer that strong rock of stability. And she felt that she needed to do something. All the experience of living with a strong woman, her mother, bubbled up in her at that moment — it was sort of dormant. Even though she had been submissive in that relationship, she rose to the occasion.

There’s also the spiritual part of this. They were a deeply religious family. And I think she felt that she was getting a message from God that she needed to go out and do this. In effect, she wound up mining her grief for a mission in life, a sense of purpose that propelled her forward.

Related Content

There’s also another unknown practical aspect of this: Suddenly, she found herself surrounded by a number of politically active people in the labor union, elected officials, and other family members who have been politically active. And I’m sure they had a great impact on her resolve as well. By the time Emmett’s body was recovered, there were several days of conversations with all of these people. And I’m sure that strengthened her as well.

Can you talk about the trial and what was going on inside and outside of the courtroom that Women of the Movement tried to convey?

One of the things that I really appreciated about the rendering of the trial was the treatment of the Black press. We saw the depiction of Simeon Booker, a mentor of mine. I was a Washington editor of Ebony and he was the bureau chief. We talked about Emmett Till and what it was like for him to cover the trial. When I was writing the book, I went back to him and discovered things that he had written not just in Jet magazine, but he also had been a Nieman Fellow and wrote an account for the Nieman Report.

I came to really fully appreciate the role of the Black advocacy press in our country. I did that through talking to him and a couple of other Black reporters who had covered the trial. The research that I did really opened my eyes to the impact of not only journalism, but particularly Black journalism in doing what journalism was supposed to do — and that was to go after the truth. I really appreciated the way the scripted series treated the Black press as being involved not only in covering the story, but also in helping to find evidence. In some ways, [it was] stepping over the line of our journalistic ethics to get involved with doing that, [but it was] because the system was failing in the South.

I think you also get some sense of the structural racism in the South in the depiction of the politicians who were involved in trying to structure the narrative, the defense attorneys, and even the jury — how people were reaching out to them at the hotel where they were sequestered.

What would Mamie Till-Mobley think about her life being turned into a TV series?

I think she would be overjoyed — and I’ve gotten this from other people who knew her for a much longer time than I did. She would be overjoyed that, one, the book was done. She was a teacher, she valued books. She knew that the story would endure as a book. And that’s what she wanted more than anything. She appreciated the possibility that the story of that book would be shared with the widest possible audience as either a motion picture and theatrical release or as a TV series. So, she would be pleased about that as well—to continue teaching. And I think she would be pleased with the portrayal of her life.