When I walk down Halsted Street with Rebecca Makkai, Boystown feels like one giant block party. It’s a warm Saturday afternoon, so doors and windows are flung open, people are laughing, and the streets are teeming with a sense of celebration.

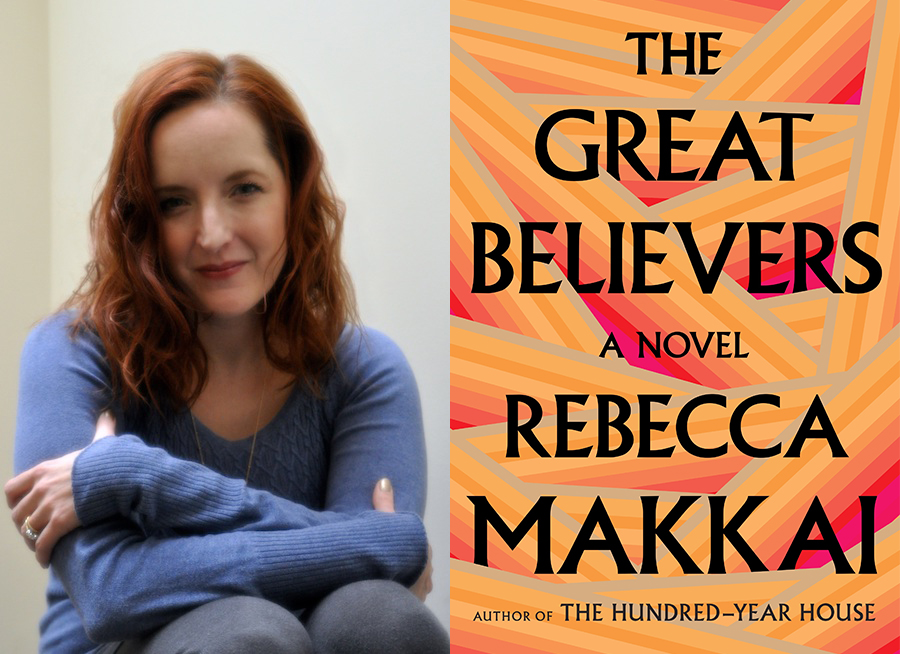

But after reading Makkai's new novel, The Great Believers — a beautiful, epic, once-in-a-lifetime book that’s destined to become as synonymous with Boystown as Sandra Cisneros' The House on Mango Street is with Pilsen — I’ll never be able to look at my adopted neighborhood with the same naïveté. The Great Believers is the story of two Chicagoans, Fiona Marcus and Yale Tishman, whose lives are irrevocably changed by the AIDS crisis. While plenty of novels have explored the toll of HIV/AIDS on New York City and San Francisco, Makkai’s is the first to focus on the epidemic in Chicago.

The title comes from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s essay, “My Generation,” in which he writes of men, like him, who came of age during World War I: "We were the great believers. I have never cared for any men as much as for these who felt the first springs when I did, and saw death ahead, and were reprieved — and who now walk the long stormy summer." This quote also serves as the novel’s epigraph, and was a way for Makkai to connect the "Lost Generation" of the 1920s with the casualties of a different kind of war, decades later.

“I have this scene where people are reminiscing about Boystown in the '80s,” she says as we walk past the Howard Brown Health clinic. It involves nostalgic customers at a Brown Elephant stand-in asking Fiona if she’s ever seen the move Philadelphia. “How could she explain that this city was a graveyard?” Makkai writes. “That they were walking every day through streets where there had been a holocaust, a mass murder of neglect and antipathy, that when they stepped through a pocket of cold air, didn't they understand that it was a ghost, it was a boy the world had spat out?”

Though she lived in the Chicago area at the time, Makkai never witnessed the AIDS crisis firsthand. Born in Lake Bluff in 1978, she lived in Edgewater for a while, but mostly grew up in the North Shore. “When my friends and I wanted to go to the city and be somewhere that was cool, we would either go to Kafein in Evanston,” she says, adding that “in the '90s, it was the shit.

"Or, we’d come down to Belmont and Halsted. I didn’t even understand what we were at the epicenter of, it just seemed like a fabulous place to be.”

Without firsthand knowledge, Makkai researched the neighborhood, the LGBTQ community, and the epidemic with the methodology of a journalist. At the Illinois Masonic Medical Center, she found the abandoned AIDS wing and sat down with her laptop to write some of the novel’s most harrowing passages. "I needed to be there,” she says. “It didn't feel right to write those scenes in a Starbucks."

At the Harold Washington Library Center, she read every single issue of Chicago’s LGBTQ newspaper, The Windy City Times, published between 1985 and 1992. “I spent a ridiculous amount of time stressing over the bathroom situation upstairs at Ann Sather’s,” she says. “I feel like most novelists would just make it up, but I really needed to have that level of detail. I didn’t want people who were here for it to be taken out of the story by my saying something stupid that wasn’t true.”

A few days after The Great Believers was published, more than 100 people crammed into Women & Children First to celebrate with Makkai, including dozens of people who helped her make the novel as accurate as possible — people who lost loved ones and marched through downtown with AIDS activist group ACT UP/Chicago. During the Q&A, someone asked Makkai why she tackled such an important subject through fiction. “People who pick up nonfiction books about AIDS already know about it, for the most part,” Makkai says. “But people who pick up a novel might stumble upon it. Fiction is going to be what gets to that lady at a book club.”

Today, thanks to the trendy restaurants and cheerful neighbors, you might walk through Boystown and mistake AIDS as a tragedy in the city’s past. But 23,824 Chicagoans — almost 1 out of every 100 — were living with HIV in 2016. The Great Believers isn’t just a memorial to those we’ve lost, but also a reminder of our present-day reality.