From as far back as he can remember, Eric Monte wanted to create some Black heroes.

Raised in the Cabrini-Green Homes in the middle of the last century, Monte became enamored with the cowboys of the silver screen. One day, at the age of 5, he was outside his building astride a makeshift hobbyhorse, and a white man asked, “Who are you supposed to be?” Monte reared back on his broomstick and said, “I’m the Lone Ranger!” “You can’t be the Lone Ranger,” the man replied. “He’s white. Everything about him is white, including his horse.” The young Monte looked more closely at the other box-office buckaroos he admired — Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, Hopalong Cassidy — and realized that they too were white. In the era of Amos ‘n’ Andy, he could find on the screen no idols who looked like him. He vowed then and there to one day make his own.

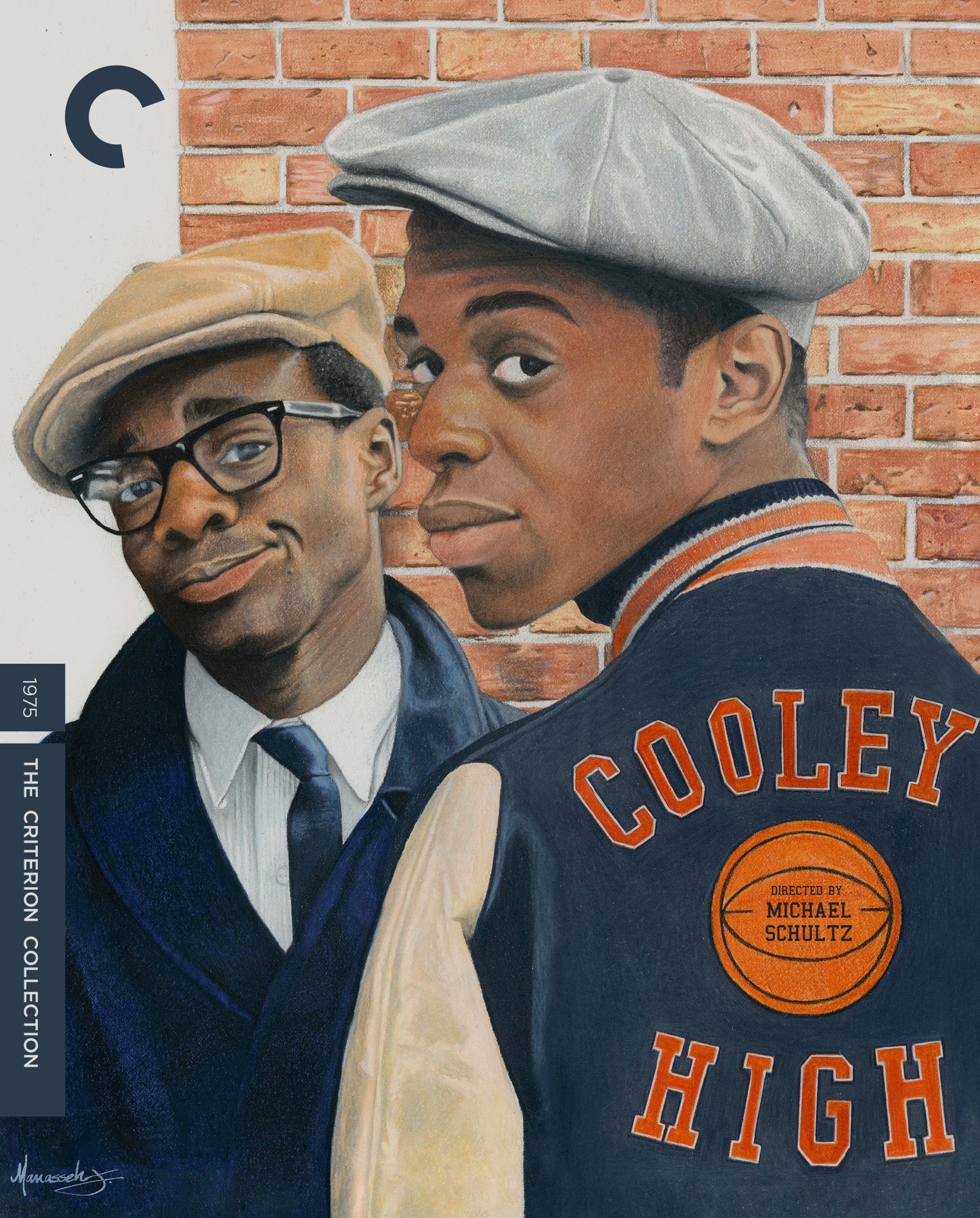

Monte moved to Los Angeles, gradually got his foot in the door as a screenwriter on All in the Family, and went on to co-create Good Times, which broke ground as the first Black two-parent family sitcom on television. But perhaps the greatest fulfillment of Monte’s childhood promise to bring to the screen heroic Black characters is Cooley High, the 1975 coming-of-age film he wrote that is considered among the most seminal movies about the Black experience in America. Last month, the Criterion Collection released a Blu-ray edition, featuring a stunning 4K digital transfer.

Made amid the blaxploitation era, with its panoply of glamorized criminals, Cooley High was an outlier: a joyful, tender portrayal of Black youth propelled by a slew of Motown hits. Into the screenplay Monte poured his experiences as a student at the now-defunct Edwin G. Cooley Vocational High School. At the center of the film is the friendship between aspiring writer Leroy “Preach” Jackson (Monte’s surrogate, played by Glynn Turman) and basketball star Richard “Cochise” Morris (Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs). On the eve of graduation in 1964, both are hoping their respective talents propel them out of the projects. In the meantime, they’re taking life as it comes: cutting class, hitching rides on the bumpers of CTA buses, belting out doo-wop harmonies on street corners, slow-dancing to soul records at parties in dimly lit apartments, wooing girls with lines of romantic poetry, pouring out a little wine “for the brothers who ain’t here.” The murder of Monte’s close friend, a standout athlete, formed the basis for the film’s tragic denouement. Ultimately that event pushed Monte to light out for L.A. to pursue his dream of becoming a writer before it was too late.

In the fall of 1974, over the course of an eventful six and a half weeks, director Michael Schultz shot Cooley High mainly in and around Cabrini-Green. The cast included just three professional actors alongside locals with little to no experience — including two scene-stealing members of a real-life street gang — which infuses every frame with an extraordinary sense of realism.

The film proved to be a surprise box-office success, earning $13 million on a budget of less than $1 million. It was the first major film for Schultz, who would go on to helm the classics Car Wash (1976) and Krush Groove (1985). At the age of 84, he remains an in-demand television director. (Earlier this year, The New York Times called Schultz “the longest-working Black director in history.”)

Cooley High had a profound influence on directors such as Spike Lee and John Singleton, whose 1991 film Boyz n the Hood is a direct homage. The movie’s impact extends into the worlds of fashion and music. Boyz II Men titled their 1991 debut album Cooleyhighharmony. Three years later, on his landmark, Illmatic, Nas rapped, “I dropped out of Cooley High, gassed up by a cokehead cutie-pie.” Last year, the Library of Congress inducted Cooley High into the National Film Registry.

Cooley High also served as a springboard for some Chicagoans. A year after the film’s premiere, Jackie Taylor, who played Cochise’s girlfriend, founded the Black Ensemble Theater, which is still going strong. Steven Williams, who notched his first screen credit as hustler Jimmy Lee, has made a long career as a character actor. The actor and filmmaker Robert Townsend, in a bit part, also made his debut; he would go on to direct, write, produce, and star in the highly regarded industry satire Hollywood Shuffle (1987), which Criterion will recognize with a Blu-ray edition in February.

But for Monte, Cooley High would be the peak. Soon after, he created What’s Happening!!, an ABC sitcom loosely based on the film. But he complained he was never properly compensated. In 1977, he filed a lawsuit accusing Norman Lear, among other producers and networks, of stealing his ideas. He reportedly received a $1 million settlement. Thereafter he found it difficult to find work. “He was effectively whiteballed,” Schultz says today. Turning to theater, Monte blew much of his settlement purse on an ill-fated production of a play he had written. That began a downward spiral. At one point, he became addicted to crack and ended up homeless.

When he now thinks back on Cooley High, Monte grows wistful. “It’s so hard to say goodbye to yesterday,” G.C. Cameron sang in the immortal ballad written for the film. And to Monte, who turned 79 on Christmas, the yesterdays of his youth feel quite distant. He has suffered multiple strokes that have limited his ability to verbally communicate, and currently resides in an assisted living facility, paid for in part with money from a fan-launched fundraising campaign this past summer. Though the roller-coaster trajectory of his life has been disorienting, he says he remains certain of one thing: “Cooley High means the name Eric Monte will live forever.”

Part I: “This Is My Life”

Eric Monte (writer): Cooley High is a true story — my story of growing up in the Cabrini-Green Homes. In the mid-1970s, I was working on the TV show Good Times and was approached to do a movie on my life growing up in Chicago. Of course, I said yes.

Steve Krantz (producer), to the Chicago Tribune in 1992: I needed a writer for a sequence in the sequel to the animated feature film Fritz the Cat, which I had produced. Norman Lear recommended Eric Monte, a young black writer who had created the successful Lear-produced television series Good Times. One day, Eric and I were talking about what it was like to grow up poor. Eric had grown up in the Cabrini-Green housing project; my experience was in New York.

Eric Monte: I had a wonderful childhood. We were poor but we had fun. Everyone looked out for one another. My mother was beautiful and hardworking. She had plenty of jobs but we were still poor, so I knew I had to do something different to make sure I wouldn’t ever have to work that hard.

I wanted to be a singer but I couldn’t sing. I started to think maybe I could be a writer because of all the lies I used to tell my mother to get out of trouble. If I could come up with those stories, I figured, I could write convincing stories for television and movies.

I attended the real Edwin G. Cooley Vocational High School. I hated school. I enjoyed reading books but found going to class boring. I didn’t want to be there. People would get in fights all the time, and I always wore a suit and tie in the hope that people wouldn’t mess with me. My friends and I would drink, chase girls, smoke weed, hang out. We’d go to dances to try and get girls. I channeled all of that into Cooley High. I never had a high-speed car chase with the police, though — I made that up for the movie.

Krantz: Later, we went into a recording studio and Eric repeated his story on tape. I edited the tape and took it to Universal Studios and said, “Here is a story with great color, texture, and characters that other Black films don’t have.”

Christopher Holmes (editor): Krantz ultimately brought the idea to American International Pictures, which gave him a production deal. Cooley High was certainly an exception at AIP. The studio typically made B movies, horror movies, blaxploitation films, teen movies. It had its own distribution company and specialized in drive-in movies aimed at a youth audience who just wanted to get out of the house and go have a stolen beer in a car.

Michael Schultz (director): How did I get involved in Cooley High? I had shot a little movie in Atlanta called Together for Days — a version of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, but instead of the Sidney Poitier character being the fish out of water, it’s a young white girl. It was Samuel L. Jackson’s first film, but the picture never got released. Later, the editor of that film was working with Steve Krantz, who at the time was developing Cooley High and looking for a director. He called Steve up and said, “You need to hire this guy Michael Schultz.”

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs (“Cochise”): Michael’s story is nuts. A few years prior to Cooley High, Michael directed a play in New York called Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie? about young street toughs. There was an up-and-coming actor who was getting a little bit of noise around town, and Michael put him in the play. The guy wound up getting a Tony Award. His name? Al Pacino. Michael would go on to have a lot of wonderful firsts with great young actors: Sam Jackson, Denzel Washington, Blair Underwood, and on and on down the line.

Michael Schultz: Steve Krantz sent me the script for Cooley High that he and Eric had been working on, and I read it. It really wasn’t a movie. It was this series of hijinks, some of them very funny. I said, “Look, I’m coming out to L.A. to do some television stuff, so I’d love to meet you and the writer, and if we have a rapport, then I’d be interested in working on the film.” And then I found out why the script really was not there yet: Eric Monte was a really good storyteller, but he had never written a screenplay for a feature film — and Steve was taking Eric’s stuff and rewriting it. So you had this older Jewish guy rewriting a young Black guy’s story, and it wasn’t working. Eric just didn’t have the skills to put a spine through the piece. I said, “Look, Steve, I’ll go to Eric’s house every day, sit down with him, and talk it out. I need you to hire a stenographer to write down all the stuff we talk about. If we do that, I think I can get a script out of him.”

Gloria Schultz (casting director; Michael’s wife): During the day, Michael would work with Eric on the script. Then in the evening, Michael would come back to the hotel, we would read the transcript of what they had talked about, and continue to make adjustments. The essential story always remained the same, but it became far more interesting as a movie.

Michael Schultz: The film is basically Eric’s life story with a little of mine thrown in. I grew up in Milwaukee and would often visit Chicago. The city was part of what was then called the Armpit of America. It was very industrial, the terminus for all these railroads, and it had the stockyards and all of that stuff. It was a grimy, gritty city back then. The thing is, when you’re a kid in whatever environment you grow up in, you look at it in a different way. It’s your home. It’s where you hang out and you have your friends. To outsiders, it may be ugly, but as a kid, you don’t look at the ugliness. You look beyond it. I wanted to capture that on film.

At its heart, Cooley High is the story of two guys — a wannabe writer, Preach, and a star basketball player, Cochise — who are best friends on the eve of high school graduation in 1964. And the death of one of them catapults the other one toward going for his dream.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: The character of Preach was basically the stand-in for Eric and his experiences growing up in Chicago. Growing up, Eric was called “Reverend” or “Rev.”

Glynn Turman (“Preach”): When he was in school, Eric Monte actually lost a friend who was an athlete. He told me they were very, very tight. That’s who he based Cochise on. That incident led to Eric splitting for Hollywood with dreams of becoming a screenwriter.

Michael Schultz: I was interested in doing the movie because it portrayed real, three-dimensional characters instead of the one-dimensional Black characters we were seeing a lot of on the screen in the blaxploitation era.

Eric Monte: When I got to Hollywood, I made a vow that I would stop the “yessir, boss” movies. I didn’t want movies to portray Black people that way. I promised not to make anything that made Black people look like stereotypes.

Michael Schultz: One of the big disagreements that I had with Eric on the script was that I took out all the street language — all the swearing, cursing. He kept saying, “You can’t do that! The kids will think it’s fake!”

Eric Monte: That’s how we talked. I kept telling Michael, “This is my life,” and he needed to listen to me, because he had never lived in Cabrini.

Michael Schultz: I told Eric, “It doesn’t need foul language. It’ll reach more people without it.” So I just took it out. Down the line, as the years passed, I realized it was a great decision. The audience can put themselves in the shoes of those kids, no matter where they come from. I thought if I could make the movie so uniformly Black, so culturally specific, it would become universal. Audiences could instead focus on the lives of these kids, the fun and the pain.

Part II: “A Production of the Community”

Michael Schultz: Once the script was finished, we had a struggle with the studio executives. They were dragging their feet and not giving us a green light to start shooting. Fall was fast approaching, and I told them, “When the Hawk hits in Chicago, there will be no shooting! Everybody will be freezing. So we gotta get going.”

Gloria Schultz: I went ahead of Michael and the rest of the crew to Chicago to start casting. I was a Broadway actress when Michael and I met. I had also helped teach freshman acting workshops at New York University, where I’d learned methods for training actors. And that was critical on Cooley High, because there were only a few professional actors in the film. Most were inexperienced. Some had done theater. Others had no experience whatsoever and were cast directly out of the neighborhood in Chicago.

Michael Schultz: As a function of the film’s limited budget, all we could afford were three SAG actors. The rest came from the community, and it was a blessing in disguise. Because a lot of the charm of the film came from those kids and them helping us tell their story of growing up in the projects.

Gloria Schultz: We wanted the film to be a production of the community. So when I got to Chicago, Eric Monte sent me to meet his mother, and through her I was introduced to Cabrini-Green. I grew up in the projects in Boston, so I felt comfortable there. We were staying in a hotel that doubled as the production headquarters. We were doing all of the auditions and other pre-production work out of a few rooms there. I worked with a wonderful Chicago talent agent, Shirley Hamilton, who typically cast mostly for locally produced commercials. At that time Chicago was home to Ebony and Jet magazines, and the city was well known for having lots of Black models. So the people who auditioned were a mix of local theater actors, models, and some entertainers.

Jackie Taylor (“Johnny Mae”): I had done a lot of stage work in Chicago, mostly plays by Black writers. But Cooley High was my first movie. From the first time I read the script, I knew that the film would be a breath of fresh air. Here was a movie about young Black people joyfully living their lives — a human story that everyone could relate to, no matter your race. I thought, “Finally somebody is writing about the community that they know.” I had grown up in Cabrini-Green. I actually knew Eric Monte when I was a kid. He was older, and I was just a little girl. Eric was very much Preach — he had those same dreams to use his intelligence and talents to rise above his circumstances and become a writer. The film, really, is about ambition, drive, wanting to be somebody. It says that as African American people, our lives are not all about what they’re showing you in the news. We have dreams and desires that rise above the negativities that were being shown on screen at that time.

Gloria Schultz: We knew from the very beginning we wanted Glynn Turman for Preach.

Glynn Turman: When I first heard about Cooley High, I was living in California. I’d been doing a lot of television — Mod Squad and The Rookies and what have you. I was also doing a lot of stage plays. Michael directed me in a 1974 play called What the Wine-Sellers Buy. That’s where he and I met. I had also been in a play that was written by Eric Monte. Both Michael and Eric championed me for the character of Preach. Eric and I had very similar upbringings and experiences as juveniles, except he was in Chicago, and I was in the projects in Manhattan.

Gloria Schultz: Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs was pretty well known, and we were very interested in him for the role of Cochise. He was just about to premiere in Welcome Back, Kotter as Freddie “Boom Boom” Washington.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: The year before Cooley High, I’d done a film called Claudine with Diahann Carroll and James Earl Jones. And so Steve Krantz and Michael Schultz and his wife Gloria became aware of me from that movie. So they invited me over to the American International Pictures office that was on 46th Street in New York City, where I was living at the time. They pointed an old black-and-white video camera at me and filmed me just talking about what I’d done. It wasn’t a formal audition. We just chatted. As I was leaving, Michael took a walk with me down the block, and we talked all the way to Times Square. What’s funny is that when we got to the corner of 46th and Broadway, there on the marquee of the theater was Claudine, the movie I was starring in. I guess Michael took it as a sign that he should cast me in Cooley High.

Gloria Schultz: When we were thinking who could play Mr. Mason, the inspiring teacher who takes an interest in helping Preach, I think Michael is the one who said, “This has gotta be Garrett Morris.” We knew Garrett from New York — he and I were in the Melvin Van Peebles musical Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death, which had a Broadway run in 1971.

Garrett Morris (“Mr. Mason”): I knew Michael as a brilliant director at the Negro Ensemble Company and other places in New York. One day he told me he wanted me for the character of a high school teacher for this new movie he was working on. It seemed perfect for me, because at that time, when I wasn’t acting on the stage, I was teaching Black kids at a public school, PS 71, on the Lower East Side. But when Michael went to the executives at the studio, they said they wanted a Sidney Poitier type — tall and handsome. Which I definitely am not! I was 5-foot-6 at the most. But I brought a street smartness to the role. For instance, there’s a scene where Mr. Mason talks to a police detective that is questioning Preach and Cochise about the auto theft. In that scene, the cop and I were smoking a joint together, which was inspired by the fact that when I started smoking marijuana, my first weed connection was a police sergeant from Long Island. As great as he was, Sidney Poitier would not have made that choice. Thankfully, Michael and Steve Krantz fought for me to be in the film.

Gloria Schultz: I had tremendous respect for Steve because he had to take a lot of heat, especially from AIP president Samuel Arkoff’s people. The studio execs wanted to cast Hollywood types. But we wanted to capture the real life of the story by casting locals.

Steven Williams (“Jimmy Lee”): In the mid-1970s, I was a Chicago model that had a desire to be an actor. One day I went to take some pictures at the office of my agency, and every goddamn actor in town was there. My agent explained that the agency had been tapped to help cast locals for a film called Cooley High. I go, “Why wasn’t I called?” She goes, “Well, they’re casting high school students. You’re too old. There’s nothing in the movie for you.” I was confused, because I was looking around the room at a bunch of Black actors around my age. One of my good friends pulled me aside and said, “Steven, I can get you in.” She was an actress but happened to be working with the production team that was doing the casting. She got me a meeting with Michael Schultz. He liked my energy. And he goes, “You’d be great for Jimmy Lee.” I got the job but didn’t report the contract back to the talent agent. I said, “Here’s that nothing you said was for me in this movie!” I basically told her, “Fuck you, kiss my ass, you’re not representing me properly.” I ended my relationship with that agency, and it kicked off my career.

Gloria Schultz: Among the locals, we also managed to come across a young Robert Townsend. He came in to audition. He was a lively personality, had the right energy, and we cast him in a minor role as a basketball player in gym class. He has one line in the movie. It became his first screen credit. One of the biggest surprises from the local casting was Corin Rogers, who played Pooter, the little guy who was friends with Preach and Cochise. He was just such a delightful kid, and he hadn’t done any real acting before that. We sent Corin’s audition back to L.A. to Michael and Steve, and all of us agreed that he was Pooter — basically the comic relief the film needed at times.

Michael Schultz: The guys who played the two thugs, Stone and Robert, they were two actual Chicago gang leaders. The way it happened was I was sitting in a car with a young Black couple who owned a drug store in the neighborhood right around the corner from Cabrini-Green. I was complaining to them that I couldn’t find the real type of characters that I needed, because the casting people were sending me these squeaky-clean Black kids who were more the commercial type. The couple I was talking to looked out the car’s windshield and said, “Oh, you mean you’re looking for those two guys across the street?” I look up, and Rick Stone and Norman Gibson are coming down the sidewalk. And I said, “Exactly! Do you know them?” The couple called the guys over to the car, and I said, “We’re making a movie called Cooley High. Can you guys read?” One of them said, “I can’t.” I said, “Well, come to the hotel. I’ll give you a script, and I’d like you to audition for these parts.”

Jackie Taylor: Rick Stone’s real name is Sherman Smith. We grew up in Cabrini-Green together. I lived on the second floor, he lived on the first floor right underneath me. We called each other brother and sister.

Michael Schultz: When Rick and Norman came to the hotel, they sat down, and the one who could read began reading the script aloud to his buddy. Soon, they started laughing. I asked, “What’s so funny?” They said, “Oh, we do this kind of stuff every day!” I knew then that we were on the right track.

Part III: “A Family Feeling on Set”

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: I still remember all the important dates. I arrived in Chicago on October 12, 1974. That’s when I first met Glynn Turman. Shooting was to begin a few days later.

Glynn Turman: When I got to Chicago, the only other time I had been to the city was when I had toured there with the original production of A Raisin in the Sun when I was about 12 years old. I just knew Chicago as someplace very cold. But it just so happened that my father lived in Chicago at that time. And as I would come to find out, I had a brother in Chicago as well.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: I liked Glynn right away. We instantly got along. And I thought he was a terrific actor. He had done a movie before that called Five on the Black Hand Side, in which he played this militant, angry young man. I had done Claudine, which was my first movie, in which I played a militant, angry young man. And for a moment, people thought we were the same guy, which we laughed about.

Glynn Turman: Lawrence and I hit it off. He’s a New York boy, I’m a New York boy. We both had a certain New York savvy and understanding of each other’s methods. So it was easy for us to become tight. And that chemistry, that friendship carried over to the film.

Gloria Schultz: Everybody blended, became pals almost immediately. We all felt excited about what we were doing, felt it was vital. There was a family kind of feeling on set.

Jackie Taylor: Michael is a genius at creating a familial atmosphere. The cast and crew developed a wonderful bond, and Michael captured that bond.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: Michael instilled in all of us a trust that allowed us to let go into the reality of the film. So we were very loose. He opened us up to not be afraid, to let something magic happen. Most of the cast had never acted in their lives. But they brought a natural quality that worked well — and they were all cool. Jackie Taylor was a sweetie. Cynthia Davis, who played Preach’s crush, Brenda — she was beyond a sweetie.

Steven Williams: Cooley High is my first screen credit. So I had no preconception of what, as an actor, it was supposed to be like to be directed. If I’d have been directed by Spielberg back then, it would’ve made no goddamn difference. It was just somebody telling me where to fucking stand, whether to pick up my hat, or whatever. All that shit was new to me. But one thing I’ve always done as an actor is try to find the truth in the words that the writer has written, the truth in the life of my character. Eric Monte based my Cooley High character, Jimmy Lee, on a real guy he knew. And I actually got to meet his parents, and they told me a little bit about him. I played Jimmy Lee as this sort of suave con man. He styles himself as a pimp — but he never had no hoes! [Laughs.]

Gloria Schultz: Rick and Norman, the gang members, were really personable. Very gentle. I held rehearsals almost every day with them and the other cast members who didn’t have acting experience. We did acting exercises and made sure they knew their lines and understood their scenes.

Jackie Taylor: Lawrence and Glynn, though they’re both great actors, didn’t come onto the set with an attitude of, “I’m a big-time Hollywood actor.” No, they were very humble and fit in well among the locals.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: The locals accepted Glynn and me, these guys from New York and California coming into town. I even got real tight with Rick and Norman, the gangsters. I tagged along with them to parties. They were like, “Man, you all right, brother!” They couldn’t believe I could hang with them. I was like, “I’m from the projects, too. I get it.” I had just turned 21. So I was also trying to date half of Chicago at the same time. [Laughs.]

Steven Williams: Larry and Glynn? They were good boys. They’d go home and study lines, and I’d go try to find me a hoe and some blow. Back then we were in two totally different worlds.

Glynn Turman: In the film, you’ll notice Preach and Cochise and the rest of the guys are running everywhere. That’s what life was like when I was growing up — always on the move, always looking for the next adventure. Eric Monte expressed that in the script, much of which seemed like it had been taken straight out of my own adolescence — stuff like ditching school and jumping on the back of a moving bus. It’s a testament to the genius of Michael’s direction that he was able to capture that youthful energy.

Gloria Schultz: Cooley High seems fast and loose, but almost everything was worked out in advance of shooting. Not down to the exact line of dialog. But given the situation, we could alter some of the script on the fly during shooting so that the dialog had a natural ring.

Michael Schultz: My style, the way I worked with the actors, whether trained or untrained, was to put them in the situation and tell them what they were trying to accomplish as a person. And because a lot of the cast of Cooley High were already in their element as locals, they didn’t need a whole lot of direction. For instance, the dance party scene — I basically put the kids in a dark apartment with some great soul music and said, “Let’s have a good time.” On set, I was playing Motown tunes as mood music, to set the tone for whatever the scene called for.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: We shot the dance party scene during one very long day. The original location was gonna be in a sub-basement. When I was a kid in New York, we would go to these little sub-basement tenements and have our little parties where the entry fee was a quarter. But when Michael was location scouting, he saw the apartment where we ultimately shot it and said, “This is where the party belongs.”

Michael Schultz: Those slow-dance parties — we used to call them “the Grind.” [Laughs.] Because it was a chance to rub up against the girl you liked.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: Filming that dance party was so much fun. I was a young man and was dancing with the beautiful Sharon Murff, who plays Loretta, the girl who says she had seen all of Cochise’s games and was his biggest fan. And so I got a little bit, well…you know. [Laughs.] When Michael said, “Cut,” all I could do is hope nobody looked down!

Jackie Taylor: The apartment we were in was full of a lot of real teens. I was 23 and married at that time, so it was nice to pretend that I was a teenager again.

Glynn Turman: The genius thing about the dance party scene is the little details. Putting a quarter in a cup to get in? That’s taken from real experience. I went to those quarter parties when I was a teenager. And the value put on the breakfront china cabinet that ultimately gets knocked over? That was so indicative of the culture of a Black family. I’ve got a breakfront cabinet in my home that was passed on to me. To this day, when the grandkids are over, it’s like, “Be careful when you walk past the breakfront. Don’t bump into it.” [Laughs.] For the film to share that kind of a detail about Black life with the world, that’s one of the things that ingratiates Cooley High.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: There’s another scene where Cochise and his girlfriend Johnny Mae, played by Jackie, are making out in the entry to an apartment building. When you’re filming anything intimate like that with somebody, that’s as close as you can get. So I made jokes, tried to keep it loose. And Jackie was just a very receptive, open, cool person. And we just went for it. That’s why that scene has a real naturalism. Honestly, I didn’t mind kissing her.

Jackie Taylor: Kissing Lawrence was the easy part — he’s so handsome. At that time, though, I was married. So there was that complication. But Michael is a very sensitive director. Whenever I had an uncomfortable feeling, he picked up on it, and he would ask, in his soft-spoken way, “What would be natural for you to do here?” He had an understanding of how to channel those uncomfortable moments into a great performance.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: We didn’t have a lot of off time. It was a tight six-and-a-half-week shoot. Every day was basically a 14- or 15-hour day. We worked hard. The hotel apartments we stayed in were outfitted with a kitchen, so I would cook spaghetti or something and have people over to eat. One night, Glynn and I wanted to just get out of there, so we went to the movies to see this film called The Gambler with James Caan. All of a sudden I pop up on the screen as a basketball player. Glynn turns and says, “You didn’t tell me you were in this movie!” [Laughs.]

Michael Schultz: Back when we had finished the first draft of the script, we got a note from one of the AIP executives that was one of the best bits of feedback I’ve ever received from a studio guy. It said something to the effect of, “This is good. Now, go write every scene in a way that you’ve never seen before.” That advice came in handy when we were trying to answer the question: “Without being cliche, how do we find out that Cochise has gotten an athletic scholarship to college?”

Gloria Schultz: We couldn’t just have him picking up the scholarship letter from a dresser or something. It had to be more interesting. At that time, our toddler son, Brandon, had a habit of putting things in the toilet at our house. In a sort of eureka moment, Michael said, “What if Cochise finds the scholarship letter in the toilet?” So we cast Brandon as Cochise’s little brother Tommy. And he had no problem whatsoever dipping the letter in the toilet.

Glynn Turman: One of my favorite onscreen moments of my whole career was the scene where I hop in the driver’s seat of Stone and Robert’s stolen car and we go on a high-speed police chase.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: We had to shoot the car chase scene twice. We shot it the first time in a then-desolate area of the South Side. But the film came back from the lab underdeveloped — it was dark and muddy. So we went and did a retake in this warehouse location. And it was nuts because in those days you didn’t have a tow — a truck that pulls the car and holds the equipment. They put a big generator in the trunk, lights and microphones in front of us, and three cameras on the hood of the car. We rehearsed the scene, and we had a walkie-talkie to communicate with the crew — but once Michael said “action,” we were on our own. And Glynn was behind the wheel driving like a complete maniac.

Glynn Turman: Almost no one on set knew that I had once been a professional driver. Though I’d started in show business young, during my struggling years while trying to sustain myself, one of my jobs was as a truck driver in New York City. Cut to seven years later, here I am in this scene, and these guys are in this car with me — Larry and the two gangster characters, Stone and Robert. So I stepped on the gas! [Laughs] I knew exactly what I was doing. I was very confident. But those other guys had no idea. These tough guys from Cabrini-Green were screaming like little girls!

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: Glynn was driving so crazy that Norman, who played Robert, he dropped character and started yelling, “Glynn, Glynn! Slow down, slow down!” And we lost it.

Glynn Turman: Larry started cracking the hell up. It was all I could do not to break up. We had a ball.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: Somehow they found a way to keep that shot in the movie. There was a great amount of trust put in us as actors, and that’s how the chemistry happened. We had a genuine caring for each other.

Glynn Turman: One of the most important characters in Cooley High is Mr. Mason, played beautifully by Garrett Morris. He’s that one teacher in the school who instills in his students a belief in their own ability to succeed. I had a Mr. Mason in my own life, who was responsible for me going to the High School of Performing Arts — the New York school that was the basis for the film Fame. To this day, I believe I would not have made it had it not been for Mr. Wilson.

Michael Schultz: As most film crews do, we had cops on hand to protect the set. A lot of them looked odd, with long hair and kind of rough around the edges. The cast members who were from the neighborhood recognized these guys and would tell us stories about how corrupt they were, how they would sell drugs to folks in the neighborhood and shoot people’s kneecaps off. As it turns out, some of those cops had just finished an undercover operation where they had made a drug bust totaling millions of dollars worth of cocaine — and something like half of it had disappeared from the police station.

Glynn Turman: I remember the night we shot the scene where Preach’s mother tells him to go get her belt so she could punish him. It was late, and we were really pushing the schedule. We had been working 12 or 13 hours. We were all worn out. The woman who played my mother was not a professional actress but was wonderful in the role. We had done the scene many, many times. At some point, Michael cut, and she said, “I ain’t doing it no more, I’m tired.” Well, the sound was still rolling, so that line got captured on tape, and during editing, they included that bit of audio. During one take, I came back and found her asleep in the chair she was sitting in.

Michael Schultz: She actually fell asleep in that chair! [Laughs.]

Eric Monte: At the end of the film, Preach reads a poem at Cochise’s gravesite: “Laughin’, rappin’, chasin’ girls, obeyin’ no laws, except the law of caring. Basketball days and high nights. No tomorrows. Unable to remember yesterday. We live for today.” That’s true to life. I did the same thing for my friend who got killed.

Glynn Turman: For the final scene, Preach’s monologue over Cochise’s grave, I had prepared and prepared and prepared. And when we got to the day of the shoot, we were able to get the master shot, but for some reason we didn’t get the close-up. Maybe a week later, we were on our way to shoot another scene, and the weather that day happened to match the weather on the day we got the master shot. So Michael said, “Pull over! We’re going to get the close-up.” I had prepared for a week, thinking that I would’ve had a full day to do it. But I did it in, I think, one take. Then we got back in the truck and kept on moving to the next scene.

Jackie Taylor: Shooting Cooley High, we didn’t feel like we were working. We felt like we were part of this community that had come together for a higher purpose. And we were all having a great time doing it.

Part IV: “Music Became Another Storyteller”

Christopher Holmes: When I took the job as editor on Cooley High, it turned out to be a recut. Michael had already worked with an editor on the film but wasn’t happy with the results.

Michael Schultz: The guy who had edited Together for Days and who recommended me for Cooley High was the first editor. When I saw the first cut of the movie, I was like, “I know I shot a better movie than this.” I loved the guy, and he had helped me get the job, but he had to go.

Christopher Holmes: The reason Michael and I got along was that he had almost the identical editing mind that I did. As an editor, I was cocky and would tell directors, “This scene is redundant of another scene — boring! We don’t need it.” Michael was the rare director who was very receptive to that kind of feedback.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: Michael was a natural editor on set. I remember there was a scene in Cooley High where there was all kinds of stuff that I was gonna say, and I had learned all my lines. Michael said, “No, no, it’s better without it.” And I said, “But I wanna say it!” Michael didn’t take any B.S., but he wasn’t mean or anything like that. He just gently said, “We don’t need it.”

Christopher Holmes: Among the film the crew had shot was all of this footage of the back of three- or four-story apartment buildings, with old, wooden exterior staircases, and clotheslines hanging from one building to another. The studio wanted to be so heavy-handed in the film’s depiction of the Chicago projects. And I told them, “I’m not gonna make that cut. I won’t do it.” They were trying to force me to include all this imagery from the street, like cars propped up on jacks with wheels missing. It was so degrading. Michael and I resisted, and that’s really where we connected.

Michael Schultz: The film’s music came together during editing. I had been using Motown music on set while we were shooting the dance party and the stuff in the cafe and whatnot. Then, while we were cutting the picture, we added more. I was just putting music in the film that I liked not knowing whether we could afford it or not. Once it was added, the music became like another storyteller.

Gloria Schultz: The music supervisor on Cooley High was a veteran named Barry De Vorzon. Thankfully, he knew Suzanne de Passe, a higher-up at Motown.

Michael Schultz: Barry told Suzanne, “Cooley High was made for Motown, and Motown was made for this movie.” Back then, nobody in Hollywood valued Motown music, so I got every song I wanted for almost nothing.

Christopher Holmes: In the opening scene, after Preach and Cooter and Cochise do their little shtick with the fake bloody nose in order to get out of class, we wanted a feeling of celebration — the kids were celebrating their freedom, running around the city. So we brought in Stevie Wonder’s “Fingertips.” To me, that nailed the picture. From that moment on, we owned the audience. After seeing that scene, nobody was going to say, “Oh, this movie’s a piece of shit.” It just wasn’t gonna happen.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: The first time Glynn and I saw the movie, it was a rough cut with no music in it, and we thought it was not a good movie. We were like, “Well, OK, another job. Big deal.” Three months later, they had color-timed it and added the Motown music, and we were mind-boggled.

Glynn Turman: When I saw the film with the music, I was just like, “Oh my god! This is crazy!” “My Girl” by the Temptations was already one of my favorite songs. And when I saw the scene where Preach and Brenda are walking past the railroad tracks and “My Girl” is playing, I was like, “Hell yeah!” The Miracles, Stevie Wonder, the Supremes — the film has got one of the greatest soundtracks ever.

A few years back, I had breakfast with Smokey Robinson. We were eating, and I said, “Smokey, when are we gonna do another movie together?” He looked at me confused. “Glynn,” he said, “what are you talking about?” I said, “Man, Cooley High!” And he was like, “Oh, yeah, right!” There are, like, three Miracles songs on that soundtrack.

Part V: “Forever Linked in Each Other’s Lives”

Eric Monte: The first time I saw the film was opening night in Chicago.

Michael Schultz: During the course of the shoot, there had been a drug bust in Chicago, and the guys who played Stone and Robert got arrested. Somehow, Steve Krantz and the people at the studio convinced the police to let those two guys out just until filming had wrapped — then it was back to jail. They got out again in time to attend the Chicago premiere in June 1976.

Glynn Turman: What made Cooley High both popular and important was that it shared a glimpse of Black culture with the rest of the world. And the rest of the world identified with it, because the portrayal was so human. It’s the Black story on screen in a way that hadn’t been told that way ever before.

Eric Monte: The film made $13 million at the box office on a budget a fraction of that. It was gratifying. I knew that if we did the film right, it would make money and last through time.

Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs: Cooley High touches on the death of a certain type of innocence. It was a time when there was a social camaraderie, a time when the village still helped raise our children.

Gloria Schultz: A year after the film was released, Norman Gibson, who played Robert, was shot in Chicago. While we were filming Cooley High, you just felt that kids like Norman had to get out of the neighborhood or they would probably someday be killed. It didn’t seem like there was an easy exit out of the community for them to seek a better life.

Glynn Turman: It was terrible to hear that Norman had gotten killed. Norman and Rick were tight. They grew up in the projects together. So Norman’s death affected Rick terribly.

Jackie Taylor: After Cooley High, Ricky went through some difficult years. He served time in prison. At some point, he called me up to ask for help, and I said, “Come work at the Black Ensemble Theater,” which I founded the year after Cooley High. That was more than 25 years ago. And he’s been working with me ever since. He’s done many productions with me, including one that I wrote specifically for him, which is called The Message Is in the Music (God Is a Black Man Named Ricky).

Garrett Morris: Cooley High played a hand in getting me on the first cast of Saturday Night Live. I had written a play that producer Lorne Michaels read, and he hired me as a writer. Lorne also wanted me to be a conduit for Black actors to be on the Not Ready for Prime Time Players. So I was bringing in people like Obba Babatundé, Trazana Beverley, and Bill Duke. But Lorne didn’t choose any of the people I brought in. Then Gilda [Radner], John [Belushi], Lorraine [Newman] and Jane [Curtain], who were already hired, told Lorne, “Look, you’ve got Garrett bringing in actors. He’s an actor himself.” Lorne wanted to see some evidence. So they said, “Have a look at this movie he made called Cooley High.” Lorne watched the film then he asked me to audition.

Steven Williams: Once Cooley High was out, suddenly I was like a little neighborhood hero among my friends. They were like, “Whoa, Steven’s in the movie? Damn, dude, I just realized you can act!” [Laughs.] Glynn and Larry gave me their numbers in Chicago. And when I finally moved out to L.A. in 1980, they were the two motherfuckers who actually responded. We are still good friends to this day.

Glynn Turman: Many of us from the cast and crew have remained friends. It was just one of those magical films that hit us all at a formative time in our lives. We all made an indelible imprint on the industry together, and so we are forever linked in each other’s lives. Occasionally we will reunite at screenings of the film. At a recent one, Cynthia Davis, who played Brenda, Preach’s love interest, in the movie, showed up. We hadn’t seen her or heard anything from her in a long time. There were lots of hugs. Cooley High bonded us for life.

Eric Monte: After Cooley High was a success, it proved to me at least that I was a great writer. I thought I would do many more films.

Michael Schultz: Eric Monte absolutely got screwed over by Hollywood. Norman Lear, who’s supposed to be this good guy, he and his production company were allegedly using what were basically Eric’s ideas but not giving him proper credit. Eric finally sued Lear and got like a million bucks in a settlement. Eric’s lawsuit was successful, but it was hard for him to work in the industry after that. By that time he was so embittered that he kind of self-destructed. Justifiably, he was angry, but the bitterness ate away at him and sent him on a downward spiral.

Eric Monte, to the Los Angeles Times, in 2006: People around me were getting high on crack and I decided to give it a try, and that was a major mistake. The only thing crack did for me was give me a tremendous desire for more. I did it for two years and gave it up.

Glynn Turman: Eric got a raw deal. People will ask, “When are they gonna do a remake of Cooley High?” I always say, “What you need to do is tell Eric Monte’s story!” That’s a hell of a true Hollywood story. But what’s remarkable about Eric isn’t his downfall, it’s his creativity.

Michael Schultz: Many years ago, I was giving a talk to film students at USC in this big auditorium. At the end, a young Black kid walks up to the stage, and he says, “Hi, I just wanted to meet you and let you know that I’m doing my version of Cooley High.” And I said, “Oh, it’s good to meet you. What’s your name?” He said, “John Singleton.” Sure enough, a year or two later, Boyz n the Hood came out and it launched into the stratosphere.

Glynn Turman: Anytime I get to Chicago — and I was there not long ago filming Fargo with Chris Rock — somebody will eventually come up to me and say, “Hey, Preach. You remember me, man? I was in the scene in Martha’s cafe.” Or they’ll say, “I was in the dance party scene.” A lot of those people are still around the city. Because of Cooley High, they think of me as somehow part of the neighborhood. There’s a warm feeling that they hold for me, and that I hold for them. Though Cabrini-Green has been torn down, the people of Chicago and I still have a bond, and I’ll cherish that as long as I live.