Suzanne Scanlon is the picture of a successful literary artist. Born in Aurora and currently a professor of creative writing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an artist-in-residence at Northwestern University, Scanlon is the author of the critically acclaimed Promising Young Women and Her 37th Year, An Index.

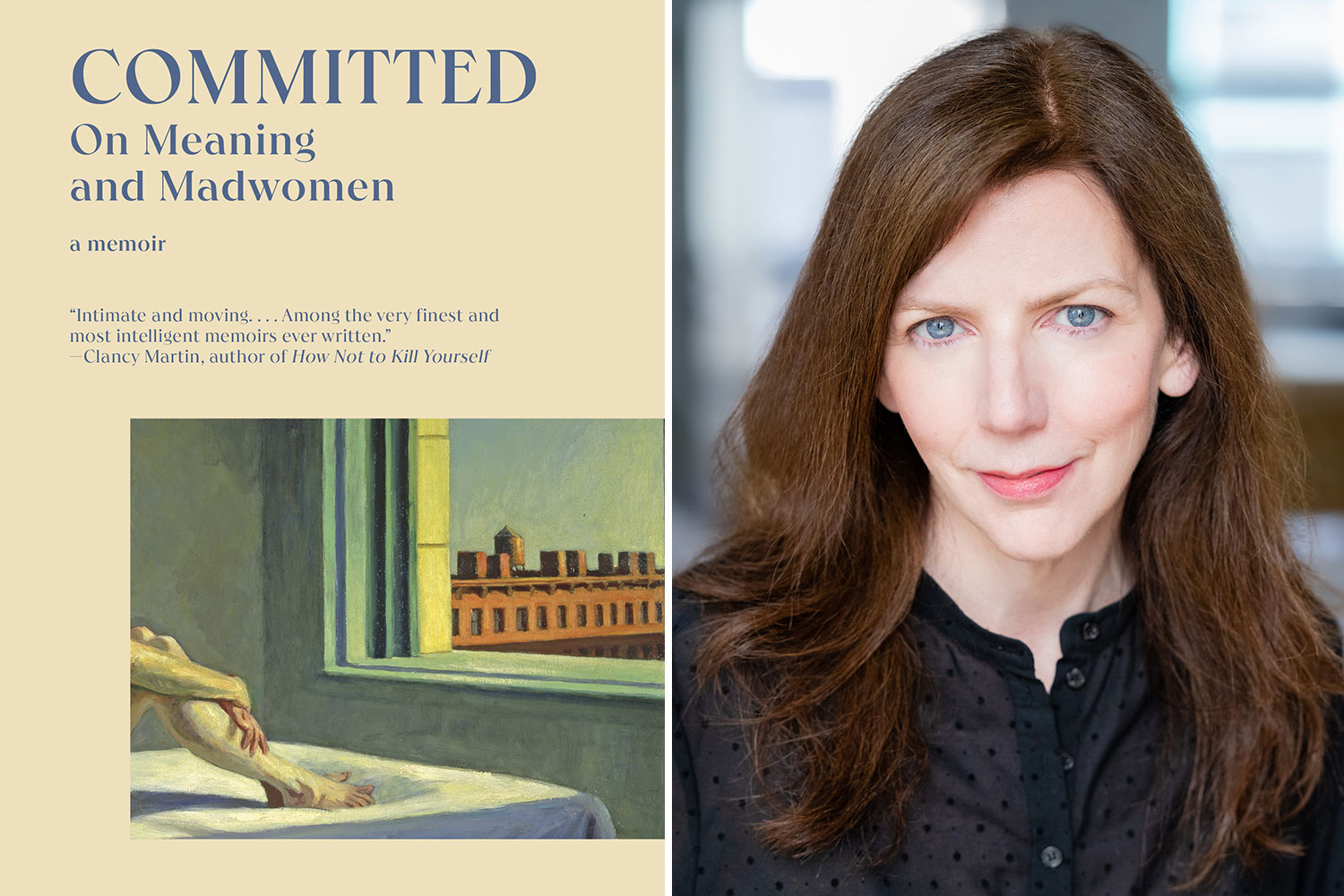

But as she explores in her latest book, Committed: On Meaning and Madwomen, out April 16, her past was not as smooth as her present position suggests. As a college student in the 1990s dealing with unresolved grief from her mother’s death when Scanlon was a child, she attempted suicide and subsequently spent almost three years living in the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

In this unconventional memoir, she situates herself in the lengthy tradition of “crazy women writers,” illuminating how this label doesn’t have to be reductive, but can provide a certain power and a path forward that permits the complexity of being a person.

Why do you choose to spend as much time — if not more — on your literary foremothers, such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Marguerite Duras, and Sylvia Plath, as you do on your actual mother?

I don’t know my mother well at all. Not even a little bit. I had just turned 9 years old when she died. So I’ve spent decades imagining her, remembering her but only the very bits or fragments of moments available to a 9-year-old. That memory is of course a reconstruction, a memory of a memory. My way to know women was to read women. If my mother had written a book, I’d be reading it. But I came to imagine these writers as my mother, as the books my mother would have written. This is all in the realm of fantasy but it was and remains quite motivating to me.

Duras’s idea that our mothers are the strangest people we’ve ever met — well that was certainly true for me, strange in her absence. The strange mystery of a mother who appeared and disappeared before I could know her. It was that vanishing that defined me. Whatever sense of self I may have had via knowing her was gone, and I suppose I’ve spent my entire life trying to create a self who would stick.

Many audiences want art to have a clear and ideally redemptive message. Your book feels refreshingly unclear and non-redemptive, as when you note, “There is a very large gap between understanding and change. Between analysis and creation. It would be nice to say this awareness or insight helped me get better, but it was not so. If anything, it fed my resentment, my rage, my sense that the world had mistreated me.” Why do people crave moral clarity from art, and why did you opt not to have your book deliver it?

For many of us trauma or great loss or grief does not resolve. There is an “obligation to recover” and much of our rhetoric around therapy has included that imperative. I think that is an intellectual stance and when something is in your body, when your personality has been shaped around a kind of brokenness, a shattering – I don’t think an intellectual understanding is going to be enough.

That’s why I resist a redemption narrative. You can learn to live with that brokenness. And if you are lucky and have resources, that’s a magnificent-enough recovery that learning to live with it — and narrative psychotherapy can help with that — can aid you in recognizing.

I think it’s harder to acknowledge that people need to be stuck in dark places, in impossible places. People who are suffering can be impossible – especially when it seems they have all the tools to recover. This is why I love Plath, she was not going to recover, so she became a writer.

If there is redemption, it is that I am alive and writing. I don’t take that for granted, it was not a fait accompli. But that doesn’t mean I have a path or instructions for anyone — or that I am a guide to getting better.

Literature isn’t self-help, but it offers a recognition of complexity and contradictory selves — I mean, people work against themselves all the time: We sabotage ourselves, or we want what isn’t good for us. The only thing the self-help industry proves is that we want to improve, but not that it’s possible. I think the wanting is very beautiful, though.

Near the end of the book, you wonder: “What if, instead of being diagnosed — being called mentally ill — what if I had been able to receive care for its own sake. To be in distress, to ask for care, to receive it. What if there were space in this world for care.” Where do you find care these days in every sense and where do you suggest the rest of us try to find it, too?

It isn’t easy, or clear. If you are lucky enough to have health insurance, or access to medical care, in many ways that still offers the best way to receive immediate care. Obviously, this is problematic, and there are many misguided treatment models, some of which I experienced. But there are many people who do care: social workers, nurses, doctors, people who still want to help people and have the patience to be present for even an impossible patient. I feel immensely grateful when I think of all of the people, strangers, who were there for me when I needed it. Part of what I want to hold in this book or negotiate is that truth alongside the truth of how harmful or dangerous it was for me, to be stuck in that system which encouraged a kind of regression and passivity.

Another place I see care is in reading and writing. For me, reading and writing were the only ways to deal with my aloneness and alienation and suffering. I felt cared for in a certain way. In writing about this suffering, it is a way to ask and to receive and to give. I am very moved by Lewis Hyde’s idea of art as a gift economy — and the gifts I have received from writers who shared their own distress, and then those who respond to my writing. This can happen through publishing but also in a classroom, and in community. And one on one, in friendship.

I do believe that writing about this, making art about it, you enter an ongoing conversation, and like many others, you may discover that writing about wanting to die or talking about wanting to die becomes a way to stop wanting to die.