Two and a half years after the Great Chicago Fire, the city was still recovering and rebuilding. In the spring of 1874, a group of prominent citizens launched a different kind of construction project: building up Chicago’s literary and intellectual culture. They formed a private club, whose members would write papers, reading them aloud at the group’s gatherings. These papers could cover just about any topic. The very first one, presented on May 18, 1874, by the Reverend L.T. Chamberlain, concerned “Physical Pain, Its Nature and the Law of Its Distribution.”

And thus, the Chicago Literary Club was born. “There was a need in a growing city to have a sense of culture,” said James McMenamin, the club’s historian. Now one of Chicago’s oldest private clubs, the organization is still going in 2024, meeting every Monday evening from October through May at the Cliff Dwellers on Michigan Avenue. At a dinner on May 20, the Chicago Literary Club will celebrate its 150th anniversary.

The club’s current president, former WGN-TV news anchor Robert Jordan, joined in 2012. “I thought that the membership was very eclectic and interesting,” he recalled. “I was impressed by the number of history buffs who are here. … I was made to feel right at home.” The first paper Jordan presented at the club sprang out of his professional experience: He examined how TV stations decide which news stories to cover. Since then, Jordan has given papers on a wide range of subjects — circadian rhythms, pickpockets, clowns, and shamanism. “I’m always coming across things that cause me to wonder,” he said.

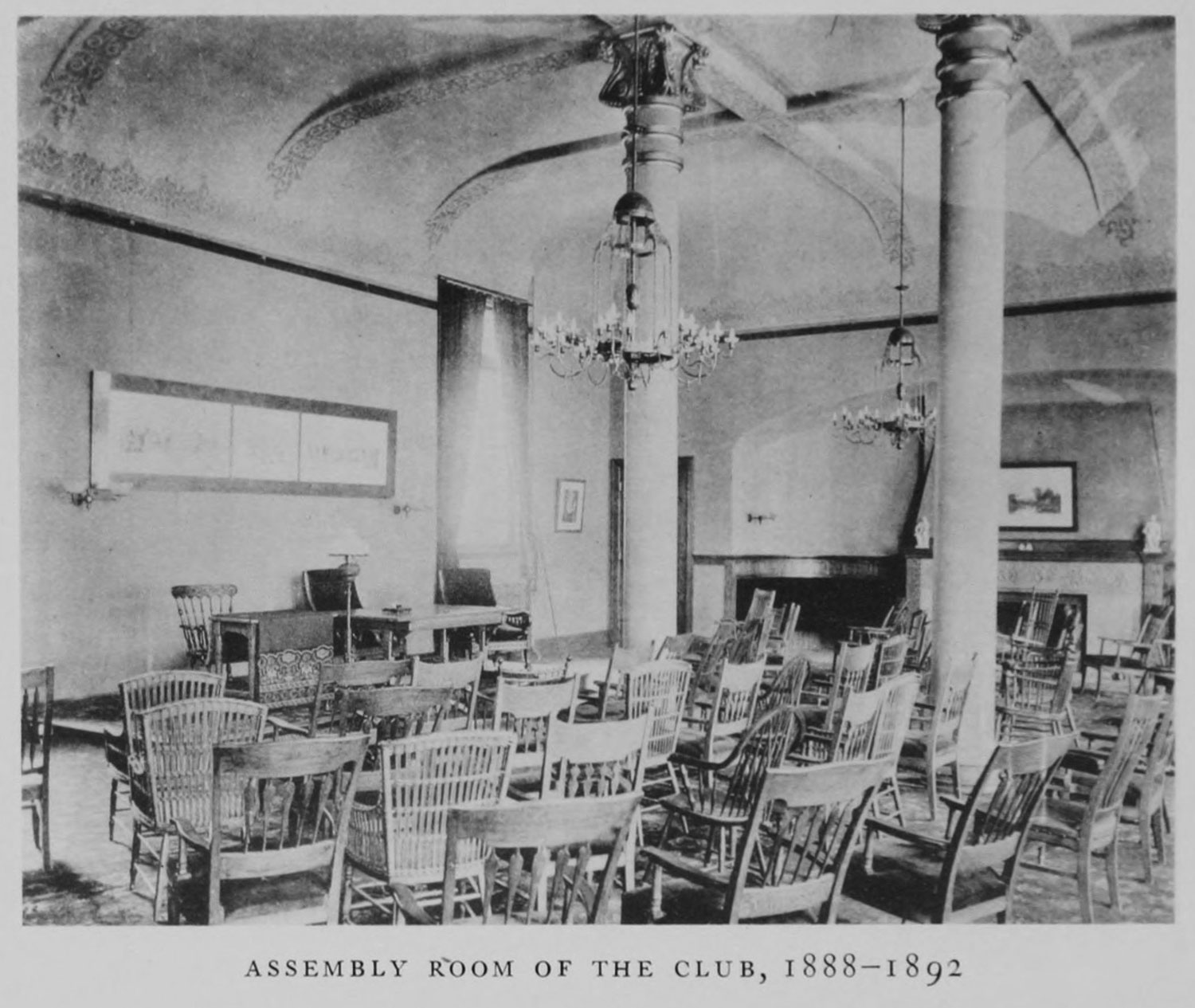

On a recent Monday, club members gathered for dinner in the Cliff Dwellers’ 22nd-floor penthouse space, sitting at tables placed together in a long row, like a single table for a huge family. “I love these dinners at the long table,” McMenamin remarked. “I meet so many interesting people.”

Afterward, they convened to a nook within the Cliff Dwellers, where member Lainie Petersen, the editor of Radio Ink magazine, stood at a lectern and read her latest paper, “The Chicago Literary Club: The Next Fifty Years.” As she spoke, she praised the format that the club’s presentations have followed for a century and a half. She was referring to rules laid down in 1874, as explained in a club history: “no paper should be subjected to criticism on the evening when read, but … it might be controverted in a subsequent paper by any essayist desiring to do so.”

That means there’s no debate immediately after a presentation. As Petersen sees it, this forces the listeners to take a pause. “This allows us to sit with our thoughts,” she said. “… You must pause, and in that pause, understanding can be gained.” Petersen called the Chicago Literary Club “a place of restraint.” The club’s sense of camaraderie is a reminder, she said, that “human beings can and should be decent to each other.”

According to a history published in 1917, the Chicago Literary Club emerged at a time when the city’s “old residents had been deprived of their books and their literary associates, and young men who were coming in large numbers to the arising city were vainly seeking for both.” And yet, “The Chicago spirit was high. Everywhere there was mental as well as physical energy and activity in evidence.”

The original idea for the club focused on the Lakeside Monthly, a Chicago-based magazine. Some of the publication’s friends “thought it would be a good thing to organize a club from among its contributors and other literary people, to extend its influence and advance the claims of literature generally in the city,” editor Francis Fisher Browne recalled in another history, published in 1926. But Browne fell sick and didn’t attend the club’s organizational meeting at the Sherman House hotel. In his absence, the club’s mission became a more general one, without any link to the magazine.

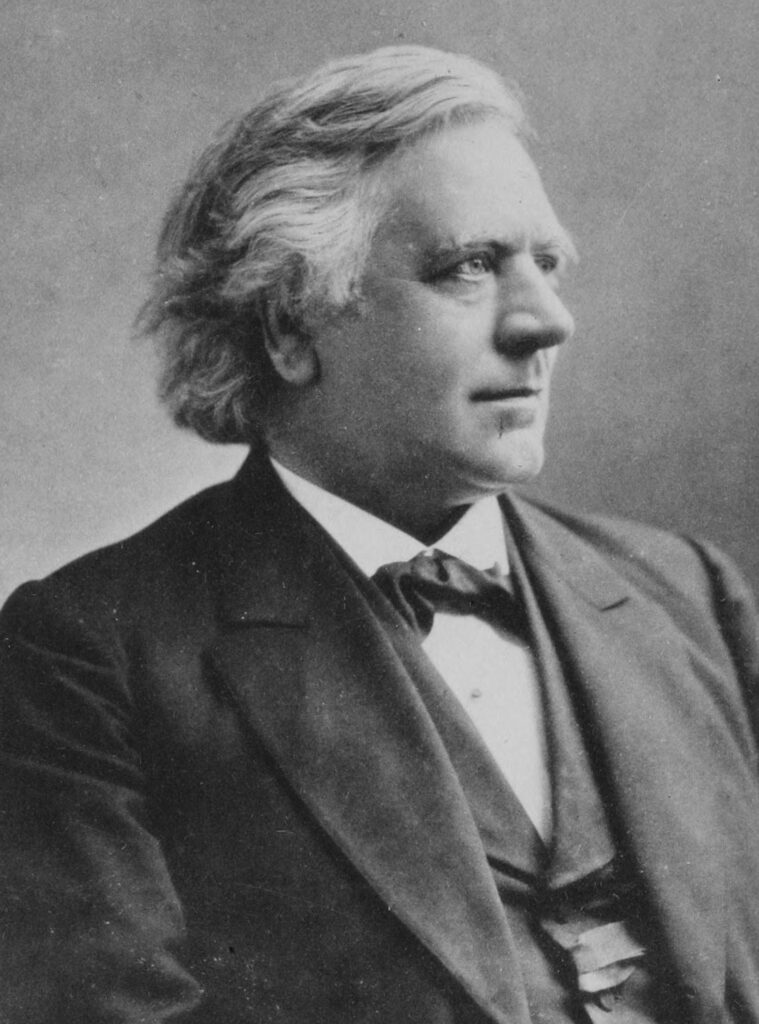

At the meeting, someone proposed a list of local millionaires and capitalists who should be invited to join. Someone else objected, arguing that “there should be one place in Chicago where money did not count.” And so, the list of wealthy people was tabled, club member Edward G. Mason later recalled. Robert Collyer, a well-known Unitarian clergyman who was acting as the group’s chairman, suggested something more like an open-door policy. “Oh, well,” he said, “I suppose if one sees another good fellow anywhere he may ask him to come in.”

In the 150 years since then, the Chicago Literary Club’s members have included noteworthy writers, like poet Edgar Lee Masters. But being a published author is not a requirement for membership. The roster has included statesmen, lawyers, educators, and people from a variety of professions. To name just a few: Robert Todd Lincoln, son of Abraham Lincoln; U.S. senator Paul Douglas; U.S. Supreme Court justice Arthur Goldberg; attorney Elmer Gertz; sculptor Lorado Taft; theologian Preston Bradley; nuclear physicist Leonard Reiffel; and architects Louis Sullivan, John Wellborn Root, William Le Baron Jenney, and Daniel Burnham, who read a paper titled “The Lake Front,” at a meeting in 1896 — some 13 years before he coauthored his famous Plan of Chicago, including its calls for preserving open space on the city’s lakefront.

Stalwart member Frank Lackner Jr. is proud of his family’s long connections with the club: One of his grandfathers, Chicago Historical Society president Clarence Augustus Burley, joined the club in 1876, followed later by Lackner’s father and an uncle. This spring, Lackner is presenting a paper titled “4,835 and Counting.”

“That’s the number of meetings since inception,” he explained. “I wanted to get that number memorialized in a title, so that people in the future could come back to that and count forward, if they ever lost track of how many times have we met.”

Lackner has been posting more and more of the papers written by club members on chilit.org, the website that the club launched in the mid-1990s.

Yolanda Deen joined the Chicago Literary Club in 1995, soon after the traditionally all-male group decided to let women join for the first time. “I was confronted with a roomful of men, and one woman,” Deen said, recalling the first meeting she attended as a guest. “I thought, I don’t know if this is for me.”

But the club’s president at the time, Ralph Fujimoto, insisted that Deen would be welcome. “So I did join, primarily because I like to write,” Deen said. “But the camaraderie in this club … is 50 percent of why we’re here all the time. It’s a really a brilliant group of people. So well educated, so well experienced, so civilized.”

Today, a quarter of the club’s 141 members are women. “The glass ceiling has been dented but not totally shattered,” Deen observed recently, when she presented “Adam and Eve in Clubland,” a paper about the history of the club opening up to women. (Like many club members, Deen relishes giving her papers titles that merely hint at their subject matter. “The titles deliberately are obscure,” she says.)

As the Chicago Literary Club marks its sesquicentennial, Jordan said the group needs to recruit younger members to carry on its traditions. “We are now making a concerted effort to bring in new members,” said Jordan, who is 80. “Our average member, I bet, is in the 70s.”

Typically, a club member invites prospective members to attend a meeting and consider joining. If you don’t know a member, you can email membership@chilit.org, and someone from the club will get in touch to answer your questions about membership.

Peterson, a member of Generation X, said she’d like to see more people from that demographic in the Chicago Literary Club. She described the club’s gatherings as a haven away from the bickering that dominates so much of today’s world. “What we have to offer is much needed by a fractured and frazzled society,” she said.