Chicago native Tracy Clark has a penchant for puzzles and writing — two strong prerequisites to become a successful mystery writer. Her debut novel, 2018’s Broken Places, earned plenty of buzz and several crime-fiction awards. A journalist by day, the South Shore resident devotes just a few early-morning hours to crafting thrillers before pivoting to her job as an editor. But she’s relentless with her writing: Since that well-received debut, subsequent books also won plaudits and trophies, including two Sue Grafton Memorial Awards (in 2020 and 2022) and the 2022 Sara Paretsky Award.

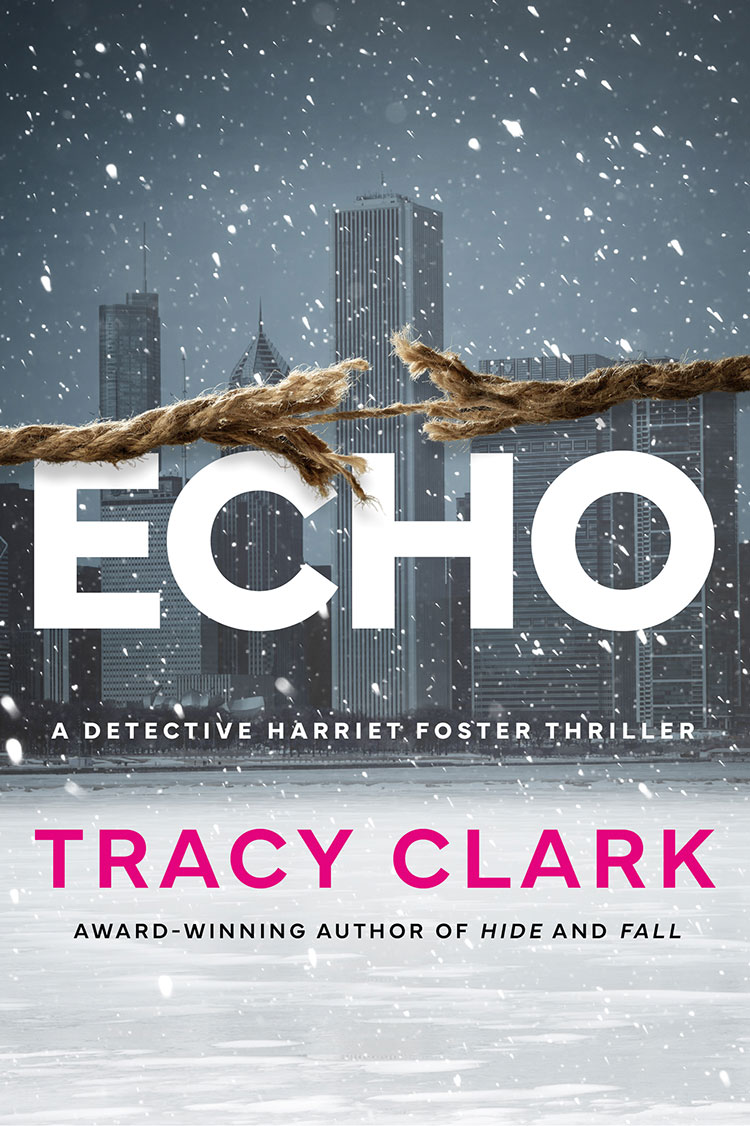

Landing this week is her seventh book, Echo (Thomas & Mercer) — the third in her Detective Harriet Foster series. The protagonist is a gifted cop but, thanks to a series of tragedies, also a broken human. Foster and her partner Detective Vera Li track down serial killers while navigating the challenges of the Chicago Police Department as, respectively, a Black woman and Asian woman.

Clark fills her page turners with plenty of local color. “I like the way Chicago feels, how it sounds, how Chicago smells. I like the vibe,” she says. “We know which neighborhoods to go to for the best pizza.” That translates to her characters’ lives: Foster, Li, and the other cops banter about soul food from Bronzeville and paczkis from Milwaukee Avenue. And in Echo, the detectives face a new kind of case: the ritual murder of a privileged student at a private college in Rogers Park. That location harkens back to the author’s undergrad days when she attended Mundelein College, now part of Loyola University.

Clark’s books also contain a healthy dose of disdain for the politics of City Hall. Indeed, in Fall, the second Detective Foster book, the victims are Chicago City Council members, each found dead with 30 dimes marking their bodies.

Clark celebrates Echo’s publication Thursday, December 5, at 7 p.m. with an appearance at The Book Cellar.

What did you read when you were a kid? Can you identify a “gateway drug” into detective stories?

I gravitated toward things with puzzles in them. We’re talking Nancy Drew and things like that — you know, any mystery or ghost story. I used to watch old black-and-white movies, The Thin Man series and Sherlock Holmes, with my mother and my grandmother, and I loved them! When I began reading mysteries, it was Agatha Christie, Dashiell Hammett, things like that. I love crime fiction. Then there was this great wave of female crime writers in the 1980s: Sara Paretsky, Sue Grafton, Valerie Wilson Wesley. I gravitated toward those strong female protagonists. I began to figure out how to put myself, or characters like me, on a page in that kind of story.

What was your journey from journalist to author?

When I was 11 or 12 years old, I would write little stories in my notebooks and hide them away. I spent years and years doing that, taking every writing course that I could possibly take in grade school and high school and in college: creative writing, editorial writing, whatever kind of writing class there was, I took it. The desire was always there; the dream was always there. But I also knew, practically, that I needed a job with a salary.

I work for the Tribune Company, where I’m an editor. I edit op-eds, comic strips, puzzles, all that fun stuff. That’s my day job. This is how my day goes: I write in the morning, then switch to my day job. Fiction on the one side, day job on the other. Even when I had a job in a building, I would write on my lunch hour: At 12 o’clock, I’d take my laptop into a room on the side and I would write my book for an hour. I’ve got 20-some years of rejection letters. You just have to hang in there until your shot comes in.

It sounds like you’ve never been a police reporter. How do you research CPD detectives’ methods?

I’ve been around cops all my life. I’ve got some in my family. I listen to their stories when they’re off duty, sitting around the table. I’m listening to not only what they talk about, but also the stuff they don’t talk about, which can be more interesting. I get into the milieu of how they talk to each other. If I get stuck while writing — and I get stuck a million times while writing a book — I can call them or text them and say, “What would happen in this situation? How would you approach this?” That’s how I get the authenticity.

Your protagonist, Harriet Foster, is much more about action than dialogue.

Some characters talk to me. I hear their voices in my head. Not Harriet! That’s like trying to bust open a rock. She’s not free with her words. Harriet, I dig and dig and dig to get to the bottom of who she is. I’ve given her a lot to deal with, haven’t I? That’s the challenge I set for myself. She’s brilliant as a cop, but when she goes home and takes that badge and that gun off, she’s stuck. It’s not until the third book that she can say, “I’m not OK. Something’s gotta change.”

You’ve created two women of color who play the roles of the primary heroes. Was one of your goals to diversify the landscape of the detective yarn?

Yeah, I guess. I always wanted to put people like me on the page. I’m not the first one to do it — just look at Walter Mosley, Valerie Wilson Wesley, Eleanor Taylor Bland. They came before me, so it’s not like I had to create this template on my own. I looked it up when I first started writing — in the Chicago Police Department, only 20-odd percent are African American. And in fact, Asian Americans are 3 percent. I wanted to put those people on the page. So here’s Detective Vera Li and Detective Harriet Foster, in a department that was not set up for them. I like that tension, that conflict, between the younger detectives with new ideas and the old officers who don’t want things to change. And then on top of that, I give them all the personal problems that they have to deal with! You never give your characters a moment’s rest. That’s what fiction is: conflict and tension.

Do you have other Harriet Foster stories in your future, or is this a finite trilogy?

Three is the optimal number, but after I finished Echo, I talked them into a fourth Harriet. That’s what I’m working on right now. It’s called Edge. It’s due at the publisher’s on the Ides of March, which is sort of ominous.

If you could spend an evening with three authors — living or dead — whom would you most like to meet?

Definitely Sue Grafton. I met her once at a book signing, but you know, you only get a few seconds. I’d love to sit with her. Agatha Christie, definitely, but I’d bring my own lunch. She’s really into poison, so I’m just going to sit in her house and ask her about her writing process, and then I’ll go to McDonald’s on the way home. Definitely those two — and then who? I don’t know. Maybe Arthur Conan Doyle. Sherlock Holmes was so original. I’d like to hear how that came about.