We lay our scene in fair Chicago. It’s Monday, April 13, 1992, 9 a.m., nary a rain cloud in sight. And yet the basements of City Hall, the Federal Reserve Bank, Marshall Field’s, and more Loop buildings are filled with water — up to 35 feet deep. Reportedly, fish are swimming in the Merchandise Mart. workers file into offices, only to be sent home. The Loop has turned into a nasty, smelly swimming pool. So where did the water come from?

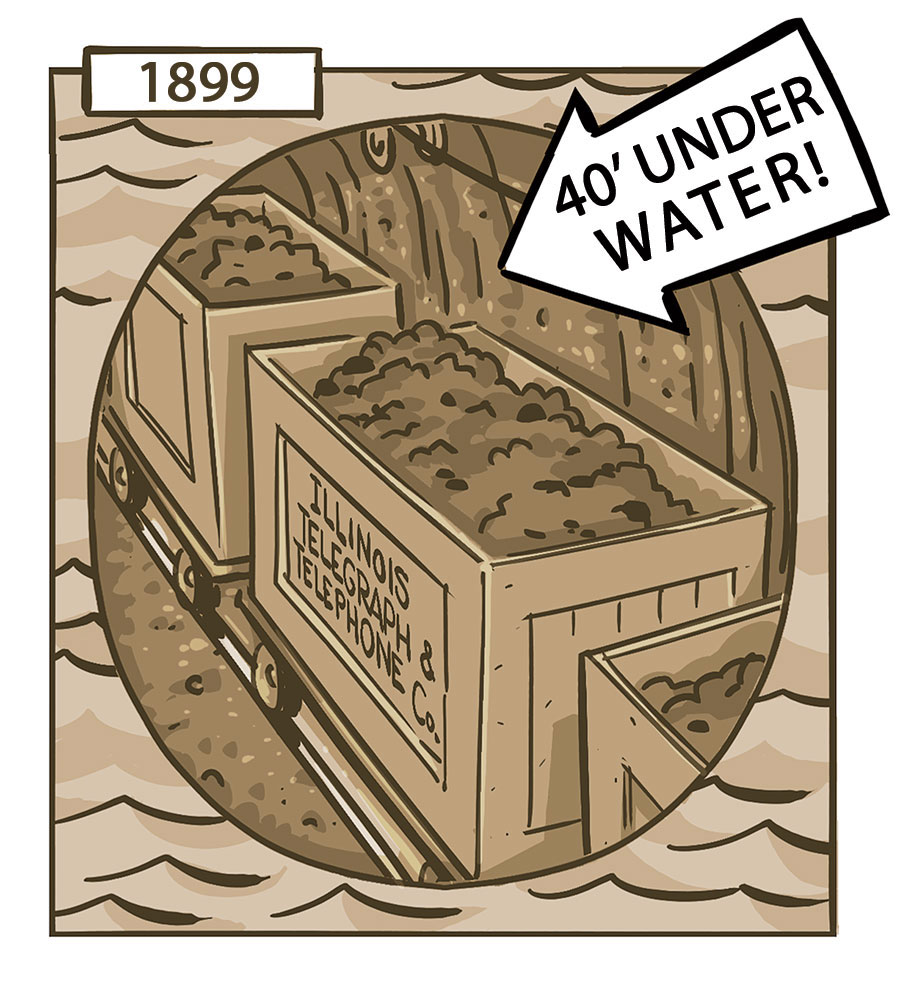

In 1899, Illinois Telegraph & Telephone laid cables 40 feet beneath the Loop. Sneakily, the tunnels the company dug for these cables were large enough for tiny freight trains. For decades, the Chicago Tunnel Company used these passages to transport coal and waste between buildings. The network was abandoned in the ’50s but remained below the city … and the river. Cue “Jaws” theme.

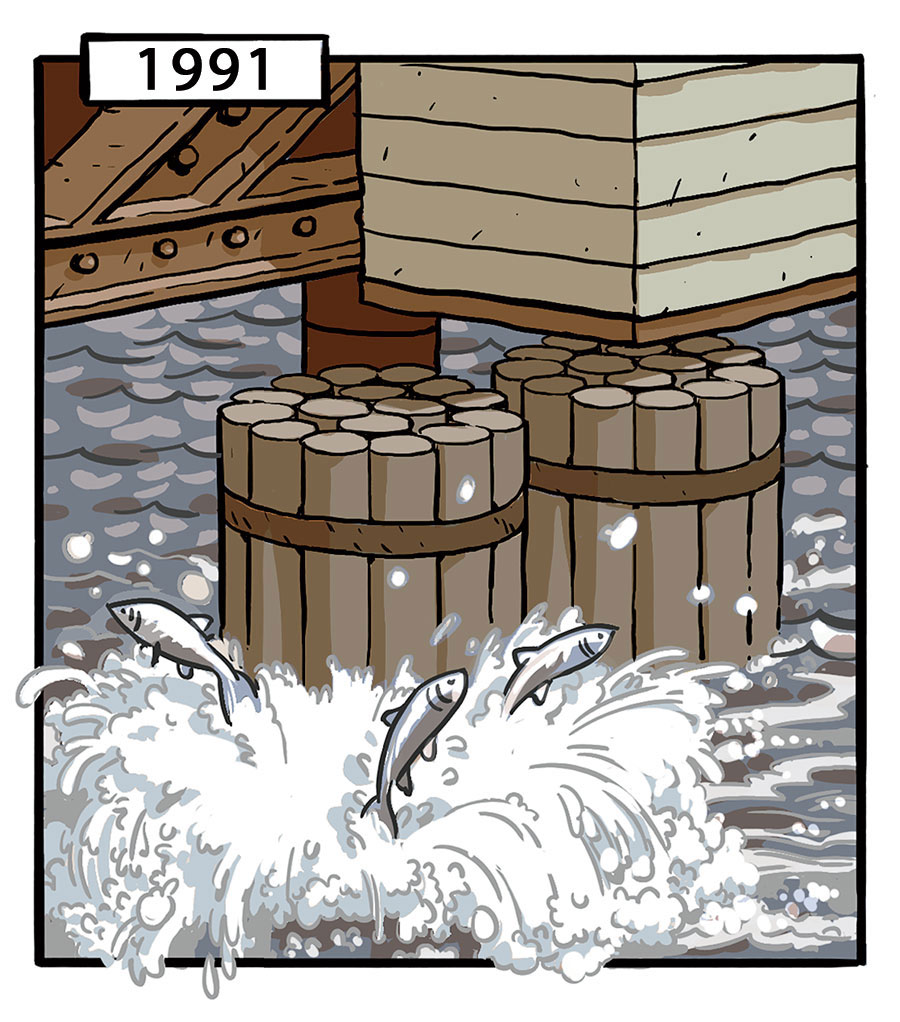

In late 1991, a contractor installing pilings while repairing the Kinzie Street Bridge unknowingly punctured clay soil between the river and a tunnel, allowing water and sediment to seep in. By April, the pressure was so great that the old train network — and the Loop basements it once serviced — began filling with millions of gallons of river water.

Plug! That! Hole! The city, The Army Corps of Engineers, and Kenny Construction filled the car-size breach under the bridge with rocks, gravel, and concrete (but probably not, as the legend goes, mattresses!). Eventually, construction teams drilled shafts into the old freight tunnel, allowing water to flow into the Deep Tunnel network beneath.

While Loop activity normalized in three days, it took another 19 days to empty the tunnels. Remediation cost: nearly $2 billion. Was it preventable? CBS reported that the city had learned of the leak that February and noted it in an early-April memo. it’s unclear if word ever got to Mayor Richard M. Daley. Heads rolled: Eight city officials lost their jobs.