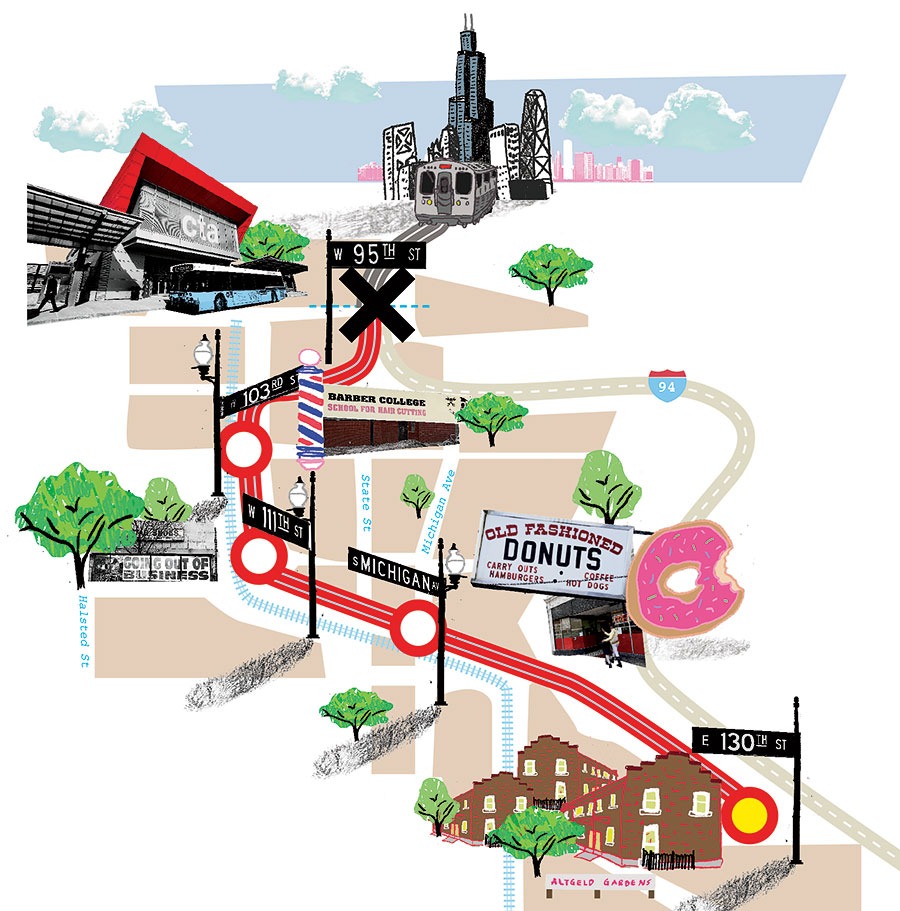

If a neighborhood can be called a transportation desert, the area around Altgeld Gardens is the Sahara. A public housing project of two-story townhouses built for World War II veterans, “the Gardens” lies between 130th Street and the Calumet River, at the city’s southern edge. The 34 South Michigan is the only Chicago Transit Authority bus serving its 4,000 residents. The nearest L stop is 95th/Dan Ryan, six miles north.

For two and a half years, Adella Bass commuted six days a week from Altgeld Gardens to a cosmetology course at Truman College in Uptown. The trip took an hour and a half each way. Bass killed the time by reading books and sleeping. “This is a transit desert, food desert, everything desert,” she says. “We are left out here to fend for ourselves.”

By the end of this decade, though, Altgeld Gardens may finally join the grid, as the last stop on an extension of the Red Line, from 95th Street to 130th Street. That would cut 30 minutes off a trip downtown. A Red Line extension has been an engineer’s dream for at least 25 years. A 1997 study by the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission proposed building new tracks by 2020. That year has come and gone, but city officials think they can finally make the $2.3 billion project happen, with money from President Joe Biden’s $1 trillion infrastructure package.

“The No. 1 priority for us as a city is extension of the Red Line with the transportation dollars,” Mayor Lori Lightfoot said at a December press conference. “It will be exponentially transformative to those South Side communities that right now don’t have great transportation options. It gives us the opportunity to think about economic development around those stops.”

Though the new L stops would certainly make commuting easier for Far South Siders, the extension alone wouldn’t guarantee economic revitalization. For that to happen, private developers will need to commit to projects in neighborhoods that haven’t seen new construction in decades. “The Far South Side is a gaping hole in our regional transportation system,” says Joseph Schwieterman, director of the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development at DePaul University. “Creating high-quality stops will send a signal that the neighborhoods are part of Chicago’s cosmopolitan, commercial mix. The city can roll out the red carpet, but it’s ultimately up to developers to take a risk.”

The new stops would be at 103rd and Eggleston, 111th and Eggleston, Michigan and 115th, and 130th and Ellis. The elevated tracks would roughly follow the Union Pacific Railroad route, through the neglected neighborhoods of Fernwood and Roseland. The CTA hopes to break ground in 2025, after completing environmental and engineering studies, and open the stops in 2029, says Leah Mooney, the authority’s director of strategic planning and policy. The CTA expects to put up half the money, with the rest coming from the feds, the state, and the city.

Corey Daurham owns Networks Barber College, which has a location on 103rd Street, between Harvard and Princeton — a dozen chairs, $10 a haircut, $5 for seniors. Other than Dollar General, it’s the only business on the block. A 103rd Street stop would “attract more students,” he says. “I’ve had students who want to sign up, but transportation is an issue. There’s a bus, but not everybody’s comfortable taking the bus.”

The next two stops would be in Roseland, which once had a busy shopping strip around 111th and Michigan, a mini Magnificent Mile. Gatelys Peoples Store, the big neighborhood department store, closed in 1981, following the white flight of the ’70s. Then went the Army-Navy outlet, the pet shop, and the Ranch, a western-themed restaurant. Now most stores are urban fashion boutiques, whose immigrant owners dispatch “callers” to the sidewalk to hawk discount T-shirts, jeans, and socks.

“It was booming,” says Ledall Edwards, owner of Edwards Fashions, a men’s store that’s one of the last holdovers from Roseland’s heyday. “It was bustling with pedestrian traffic. Ninety percent occupancy. Now some of the blocks are less than 10 percent.”

New L stops will make Roseland a commuter neighborhood, Edwards hopes: “You’ve got to bring these people back, and the only way to bring them back is new construction, new housing.”

With input from residents and the city’s Department of Planning and Development, the CTA is drawing up “transit-supportive development” plans for the four stops. The authority has identified a four-acre vacant lot across the street from the 111th Street stop as a potential site of two-flats and townhouses, some affordable. Near 103rd, it’s mapped out homes for rehab and vacant lots for new construction. The Michigan Avenue stop, which will have a parking deck, could support a 75-unit mixed-use building, with retail on the bottom floor. “We’re not a developer, but we work with land-use agencies,” says Mooney.

Altgeld Gardens will be a tougher sell to developers. Right now, there’s only one business there: Garden Fast Food, a hot dog stand with a hand-lettered menu above a bulletproof-glass-enclosed counter. Residents without cars take the 34 to buy groceries at Family Dollar or Walmart, carrying them home on “crowded buses, passing through crowded people, those germs,” says Bass.

Cheryl Johnson, executive director of People for Community Recovery, an Altgeld Gardens advocacy group, hopes an L stop will bring “at least a small commercial strip with a coffee café and a bookstore, even a little store to grab a gallon of milk or bread. We don’t have anything in this area.”

That’s not a promise the CTA can make. L stations may have a concession, such as a Dunkin’ doughnut shop, says spokesperson Brian Steele, but the authority does not build large commercial spaces. The 130th station will be designed to leave room for development on Chicago Housing Authority land. However, says Mooney, the tenant may have to be a nonprofit with “a desire to make something happen because it’s the right thing to do.” She adds: “Altgeld Gardens is going to require a more creative solution. It’s always going to be a challenging area because it’s so isolated.”

Altgeld Gardens is a housing project without L service. The Red Line extension will transform it into a housing project with L service. That may not change the Gardens’ commercial landscape, but it will at least make getting downtown less of a hassle for Chicagoans who have long felt deserted by the city’s transit system.