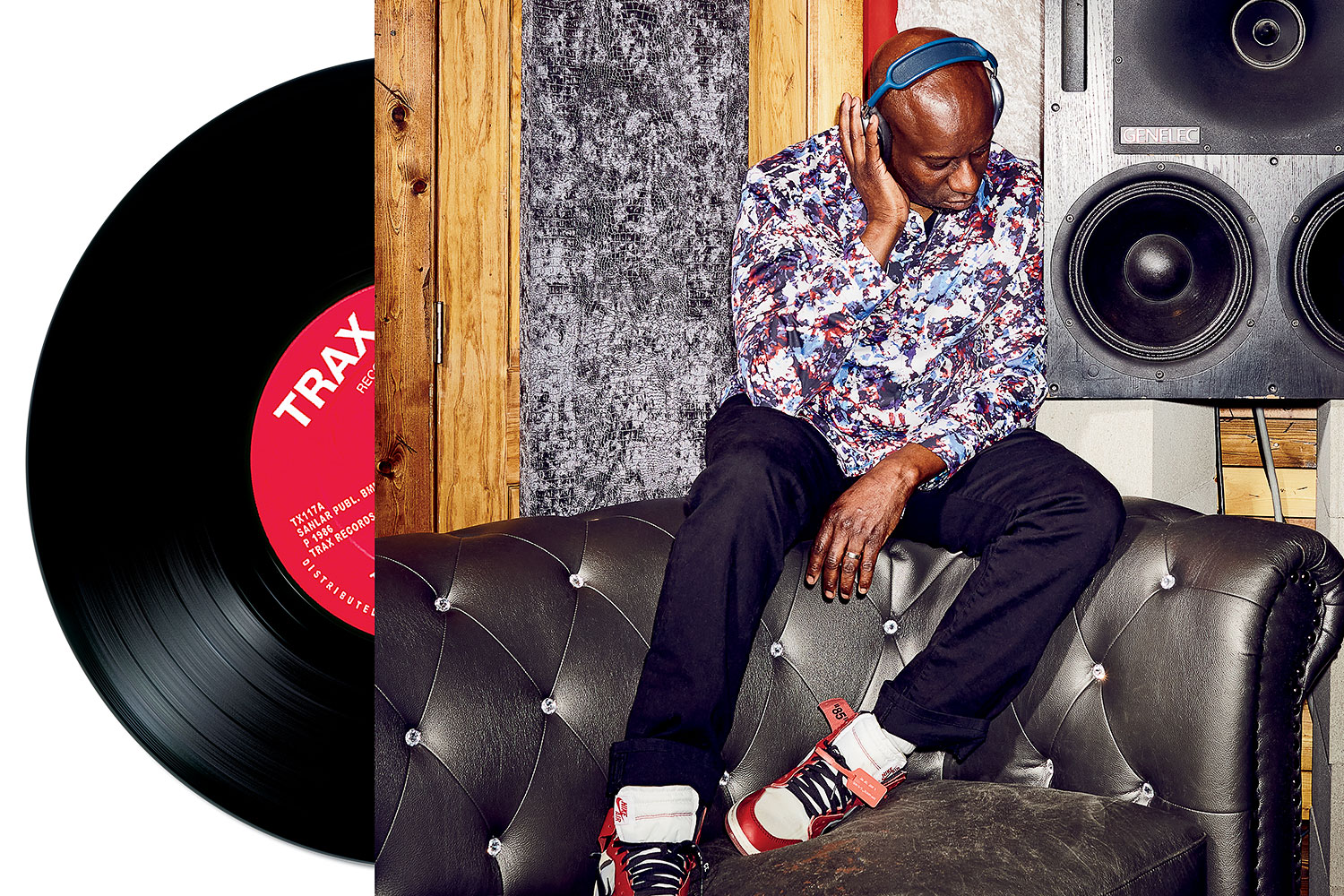

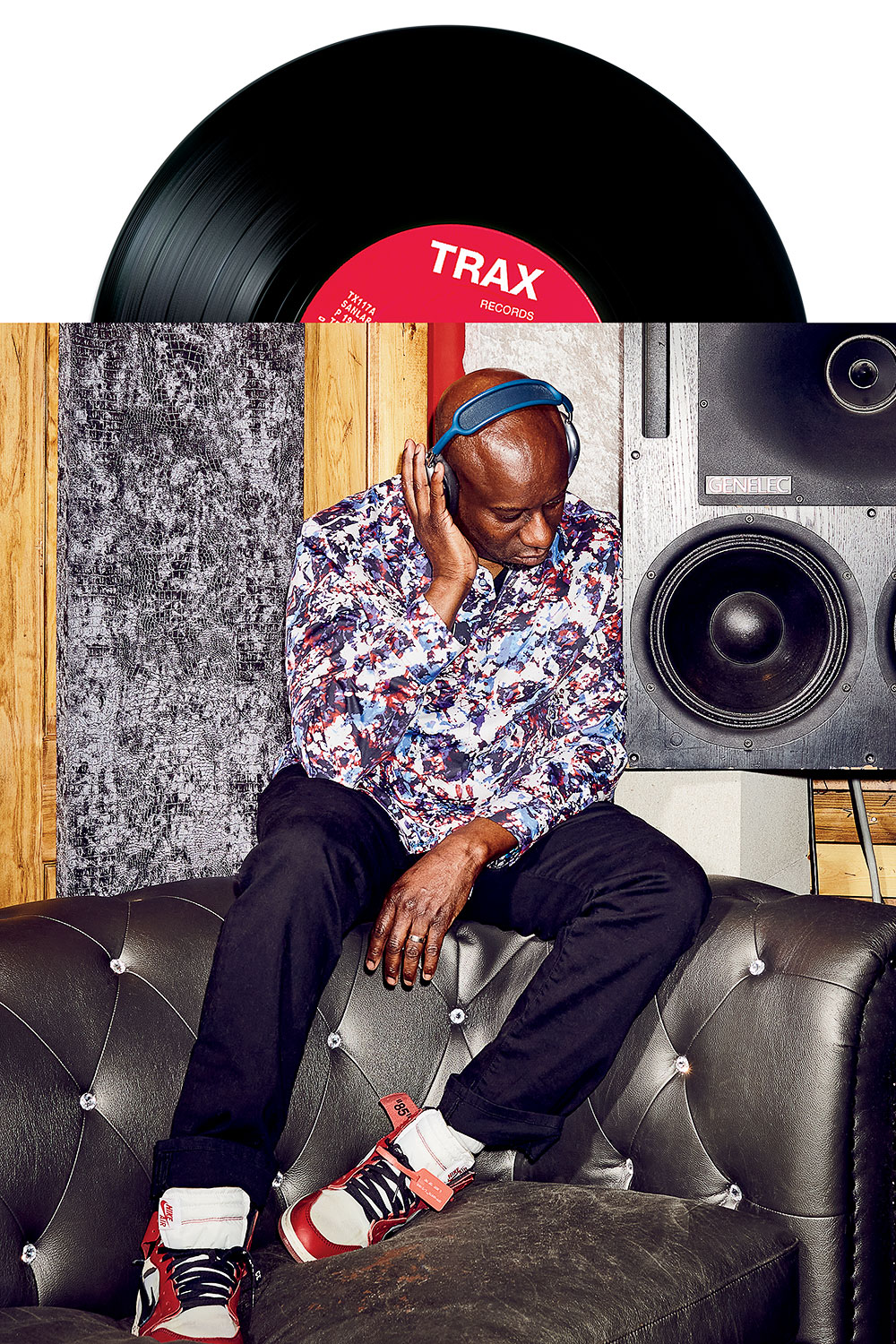

Seated behind the console in the basement studio of his Highland Park home, Vince Lawrence is in his element. This is where he produces dance records that make the floors shake, though now he’s cranking up an oldie: the Jackson 5’s “Forever Came Today,” the group’s 1975 disco-style remake of a Supremes song. As the beat blasts from the room’s 20 speakers, some of which rest on cinder blocks, Lawrence describes what a formative record this was for him and, by extension, for Chicago house music. “I think every good producer has to be a musicologist,” he says.

Evidence of Lawrence’s success lines the walls: gold and platinum records honoring his production work on Destiny’s Child’s singles “Girl” and “Soldier,” R&B crooner Joe’s “Stutter,” and former B2K member Omarion’s “Ice Box.” But long before Lawrence worked on these hits, the South Side native helped pioneer a music genre, one birthed in Chicago in the 1980s: house. Fusing disco with electronic instrumentation, house music artists packed dance floors and sold records not just in Chicago but around the globe. Trax Records, the label Lawrence helped found, was at the center of it all, putting the music on vinyl for the first time and releasing some of house’s biggest hits, including Marshall Jefferson’s “Move Your Body” and Frankie Knuckles’s “Baby Wants to Ride.”

Dressed in a gray hoodie and sporting a trim goatee, Lawrence is a young-looking 59. He clicks on a project he’s currently working on, a series of new songs by Chicago singer Jeanette Thomas, who had a house hit back in 1987 called “Shake Your Body.” The speakers throb as the playback booms at a rib-rattling level.

Lawrence helped launch house, and house, in turn, helped launch Lawrence’s career as a producer. But not every artist was so lucky. Lawrence can recite the names of others who had hits for Trax yet face significant financial struggles today — even as their music has generated licensing income and royalties for someone. “I’ve been an entrepreneur since I was 15,” Lawrence says. “I’m OK. But there are so many people who aren’t.”

The reason for that is the music business’s oldest story: Lawrence claims the label and its owner, Trax cofounder Larry Sherman, ripped them off. Sherman died three years ago, but Lawrence and many of his fellow labelmates are still around — and they’re taking action.

Last October, Lawrence filed a federal lawsuit against the current incarnation of Trax Records and its owners: Sandyee Sherman, who was married to Larry Sherman when he died, and Rachael Cain, Sherman’s ex-wife and a house artist known as Screamin’ Rachael, who received half the business in her divorce settlement. The suit alleges that the label failed to pay royalties on the artists’ music it licensed and sold — and that in many cases the label didn’t own the song rights in the first place. Joining Lawrence as plaintiffs are more than 20 former Trax artists, including house icons Jefferson, Jesse Saunders, Jamie Principle, and Ralphi Rosario.

But the lawsuit goes beyond music rights to the very identity of Trax. It asserts that Lawrence came up with the name and created the logo (an all-caps, slanted “Trax Records,” a nod to the graphic approach of the British dance band Frankie Goes to Hollywood). And while Cain and Sandyee Sherman pursue parallel visions for Trax’s future, Lawrence contends that he never relinquished his share of the label after he and Saunders cofounded Trax with Sherman. In the suit, Lawrence asks for at least $1 million in damages and ownership of the Trax trademark and the rights to all his songs. He also intends to see his fellow artists emerge with the rights to the music they created — and compensation for the use of their work.

“At some point someone has to stand up and punch a bully in the mouth,” Lawrence says. “It took me 30 years to realize that I was supposed to be that person.”

Imagine taking a time machine to Detroit for the birth of Motown Records, to Memphis for the launching of Sun Studio and Stax Records, or to New York City for the early days of hip-hop. In those places you’d find artistic visionaries in their formative days: Smokey Robinson, the Supremes, and Stevie Wonder; Elvis Presley and Otis Redding; Grandmaster Flash, Run-DMC, and so many others.

Now set that time machine for Chicago in the early 1980s, where a different collection of enterprising, predominantly Black young artists was innovating and hustling to create a vibrant new scene: house music. DJs like Farley “Jackmaster” Funk, Ron Hardy, and Frankie Knuckles were spinning their electronic dance mixes at the Warehouse in the West Loop and the Music Box downtown, packing those clubs. It was a fresh genre, one forged out of disco and refined on the dance floors of Chicago.

“This is the greatest misappropriation of Black culture since Chess Records,” says Vince Lawrence. “And it’s in some ways worse, because with Chess Records every artist sold their music for a Cadillac. Nobody got any Cadillacs at Trax.”

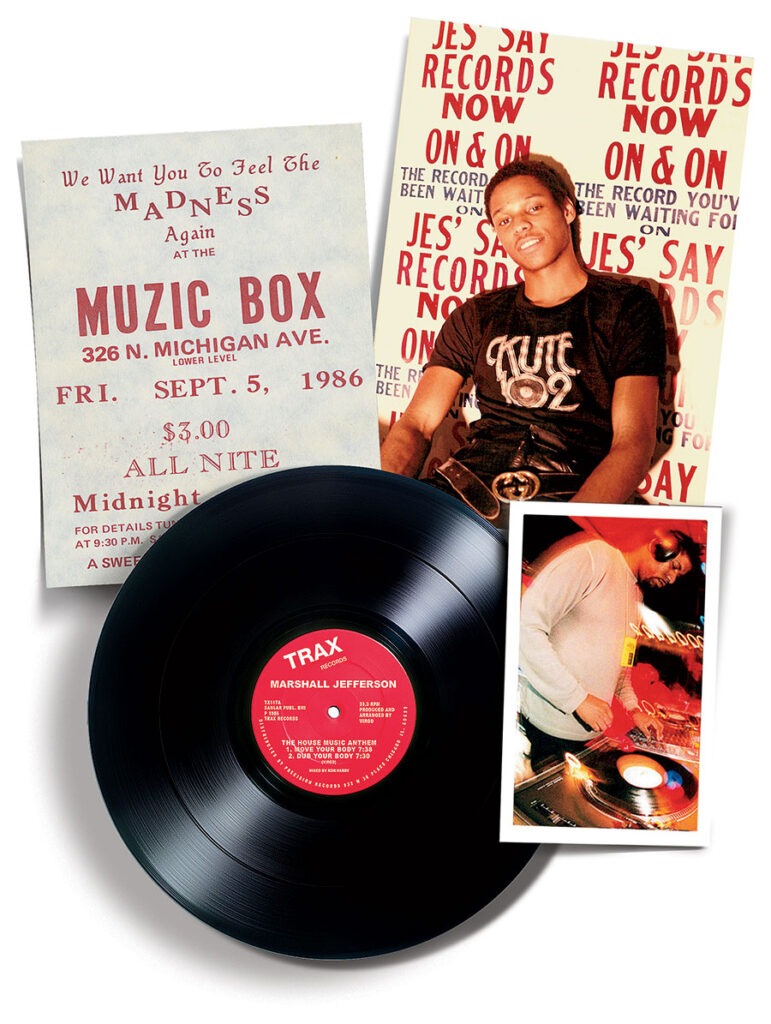

But house music wasn’t a phenomenon on record until Vince Lawrence helped make it one. In 1984, he was working lights at the Playground, a teen club on South Michigan Avenue, when he and a DJ named Jesse Saunders recorded a song called “On and On.” They took it to a local businessman who owned a pressing plant in Bridgeport: Larry Sherman. The two paid him to cut the song as a single. Lawrence says he got it played on local radio and at clubs and sold it to record stores, and soon they were moving so many copies that they couldn’t afford to pay in advance to press such a large number.

So, according to Lawrence’s suit, they made a proposal: If Sherman pressed their records, Lawrence and Saunders would sell them, and they’d all split the proceeds. Lawrence recalls Sherman being dubious that they could sell the several thousand copies they wanted to order.

“Who’s buying these records?” Lawrence remembers Sherman asking.

“I have to show you,” Lawrence responded. He picked up Sherman at his Hinsdale home late one Friday night and took him to the Playground. Saunders, stationed in the DJ booth, spun “On and On,” and the dance floor exploded as a couple thousand mostly Black teenagers moved ecstatically to their music.

“That’s who’s buying them,” Lawrence said.

“You’ve got a deal,” Sherman replied, according to Lawrence.

This handshake agreement that launched Trax was a pivotal moment in Lawrence’s fledgling music career, which had begun during his teenage years in Roseland. When he was 14, his father couldn’t afford to send him to join his friends at an overnight YMCA summer camp. Instead, he connected his son with the manager of a Chicago funk musician who went by Captain Sky and was known for his flashy, futuristic costumes and a song called “Super Sporm.” Captain Sky needed a pyrotechnician for his East Coast tour that summer of 1978, and Lawrence got the job. By the time Lawrence returned home, he says, “I wanted to be in music, and I knew I wanted to be the synthesizer guy because that was scientific, and I was pretty good at science.”

Lawrence saved up to buy a synthesizer while delivering newspapers to Hyde Park high-rises and working as an Andy Frain usher at concert venues and Comiskey Park. He was at the ballpark on July 12, 1979, when, between games of a White Sox double-header, WLUP disc jockey Steve Dahl blew up a crate of records, instigating the notorious Disco Demolition Night riot. “How ironic is it that the guy who started house music was present to witness the death of disco?” Lawrence asks with a wry smile.

After buying a Moog Prodigy synthesizer, Lawrence started a band called Z Factor. His father gave him studio time as a present to mark his graduation from Lake View High School, and Lawrence used it to record a new wave synth-pop song, “(I Like to Do It in) Fast Cars.” Lawrence took the single to radio station WGCI and the Playground, where he ended up befriending Saunders. It wasn’t long before they were collaborating.

Their first song together was a synth-dance tune called “Fantasy,” for which they hired a singer from the punk world: none other than Screamin’ Rachael Cain. Then came “On and On,” credited to Saunders and released on their own label, Jes Say. They followed that up with “Funk-U-Up,” also cowritten by the duo and released under Saunders’s name. Lawrence says it became the second-most-played song on WGCI that year. Around that time, Lawrence recalls, he and Saunders pitched Sherman on what became the Trax partnership: “I named the label, I designed the logo, and we’re off to the races.”

The first Trax single — called “Wanna Dance?” and credited to Le’ Noiz — came after Saunders and Lawrence found a synth sample of the Three Stooges’ Curly saying, “Soitenly!” They laid down a LinnDrum beat, and when Saunders asks, “Wanna dance?” Curly replies, “Soitenly!” over and over. With that bit of goofiness, house music’s most significant label was born.

Joe Shanahan, owner of the Wrigleyville dance club Smartbar, loved the “punk rock” energy of the genre’s early days: “It was a do-it-yourself ethos where guys like Vince and Jesse were making records on a Tuesday and had them in the DJs’ hands on a Thursday and Friday, and a week later everybody knew the songs. I thought that was incredible, and it was like, Oh my gosh, this is happening in our city.”

The fervor spread far beyond Chicago. Lawrence says he would sell anywhere from 15,000 to 20,000 records during a weeklong trip to New York. Shanahan realized the full impact of house music’s breakthrough during a visit to the Haçienda, a renowned dance club in Manchester, England: “I’m standing in the middle of the room hearing ‘Move Your Body,’ and a thousand people are going completely insane, jumping up and down, so excited to hear this Chicago sound.”

Lawrence and Sherman grew close as house music was taking off. At age 18, Lawrence was living in Sherman’s house to avoid tensions with his stepfather. He refers to Sherman as an uncle, describing him as a “tubby guy with a Beatles kind of mop” who had “funny stories about his days selling Corvettes of questionable origin.” Sherman was also, as Lawrence puts it, “friggin’ smart,” having bought the Bridgeport pressing plant in order to mass-produce 78 rpm records for Wurlitzer jukeboxes. Lawrence worked at the factory, where he learned mastering and metal plating.

Sherman, meanwhile, was proving a quick study in the fledgling house music industry. During the early years, Lawrence says, Sherman urged him to write a song with “house music anthem” in the title. “It’s the only one; it’s the anthem,” Lawrence recalls Sherman explaining to him. “You’ll sell tons of copies forever.” Lawrence resisted, but when Marshall Jefferson, then a producer living in Chicago, approached Sherman in 1986 about releasing “Move Your Body” on Trax, Sherman convinced him to add “The House Music Anthem” to the title. Sherman’s instinct turned out to be savvy, as the song lived up to its billing and became a smash.

During this period, Lawrence continued to produce and perform on Trax recordings and to bring other artists’ work to the label to be pressed as singles. Still, according to the suit, he and Saunders “never received compensation for their music or their work.”

“I was selling crap tons of ‘Move Your Body,’ and the money was being used to buy the parts needed to build the expanded pressing plant,” Lawrence says, referring to a new facility, also in Bridgeport, that Sherman was building to keep up with demand. “And I was getting, like, the bare minimum, with the understanding that once the plant was up and operating at capacity, he would make it right.”

Each morning, the two would leave Sherman’s house together to check on the plant’s construction. If the facility needed a new boiler, Lawrence knew how many records he had to sell to cover the costs. “Then Larry bounced a check on the fucking guy who sold us the boiler,” Lawrence recalls. “I think he got put in jail for a minute.”

Lawrence grew restless a couple of years into Trax’s existence. He launched a new dance-music act, Bang Orchestra!, with a singer named Evie, and Geffen Records signed them in 1986. Their single “Sample That!” hit No. 5 on Billboard’s dance chart, though the label never released a full album. Around the same time, Geffen also signed Saunders’s group, Jesse’s Gang, to the label, resulting in the Top 10 club hit “I’m Back Again” and the album Center of Attraction.

The two wanted to keep expanding their artistic horizons, and Lawrence says he was tired of being stiffed for his Trax work, so he and Saunders drifted away from the label. “It’s pretty easy to keep your cut when you’re the guy collecting the cash,” Lawrence says. “But it got bigger than that really fast, and we just weren’t getting ours. And after a while, we’re like, You know, fuck this.”

Few Chicago labels are more iconic than Chess Records. Established in 1950, it became a showcase for blues, R&B, and early rock ’n’ roll artists such as Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Chuck Berry, and Bo Diddley. But the label’s notoriously exploitative treatment of artists came back to haunt it in the 1970s when Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, and Muddy Waters sued Chess for underpayment of royalties and received quick settlements, with Waters and Dixon also reportedly regaining ownership of their songs.

Lawrence brings up this precedent when talking about Trax’s legacy: “This is the greatest misappropriation of Black culture since Chess Records, and it’s in some ways worse, because with Chess Records every artist sold their music for a Cadillac. Nobody got any Cadillacs at Trax.”

That includes Marshall Jefferson, who now lives in London. He wrote, produced, and arranged various singles for Trax, including On the House’s “Let’s Get Busy” and “Give Me Back the Love,” Sleezy D’s “I’ve Lost Control,” and Jungle Wonz’s “The Jungle,” but he says he never received any royalties on those songs. Often, Jefferson says, there wasn’t even a contract in place: “Some of the songs Larry just put out without anything being signed or paid. I’d pay him $1,500 to press up a thousand copies of something. Then he would find out it was hot in the clubs and just would put it out on Trax Records. Some of the songs I never even got a refund for my $1,500.”

None of those, though, were as big a hit as “Move Your Body.” And while a royalty deal was in place for that one, Jefferson says, he “never received anything” from Trax or Sherman: “He breached the contract.” (Jefferson says he eventually made money on the song by rerecording it for other labels.)

“We were all kids who didn’t know anything about the industry, man, and everybody got screwed over by Larry,” says Grammy-winning producer Maurice Joshua. “This could have been still going on and still thriving if everyone wasn’t being greedy.”

Jefferson’s claims are echoed by others who say they were shortchanged by Sherman. Producer Maurice Joshua, who would go on to win a Grammy for his remix of Beyoncé’s “Crazy in Love,” is another plaintiff in the suit. He met with Sherman because the label owner had heard about his song “I Gotta Big Dick” and wanted to release it. Joshua says Sherman agreed to pay him and his partner $2,500 to record a three-song EP, which was released in 1988. “We were young, and that was a lot of money to us then,” Joshua says. But he hadn’t realized that Sherman would deduct the recording and mixing costs, leaving Joshua and his partner with just $500 to split. At least Sherman had promised to share royalties when they came in, Joshua told himself at the time.

For the EP’s flip side, Joshua recorded two other songs, one of which was “This Is Acid,” a celebration of Chicago’s new acid-house sound. It became a breakout hit, prompting A&M Records to pick it up for its short-lived dance imprint, Vendetta Records. That release had a two-week stay at No. 1 on Billboard’s dance club chart in 1989, yet Joshua says he didn’t even know the major label had acquired and released it until a New York booking agent called, wanting to send him out on tour. “We traveled on that record for a year straight,” Joshua says, adding that when he visited A&M’s offices, he was told that the single had sold 400,000 copies.

But according to Joshua, he never received a penny for the song beyond the $500 advance, including years later when “This Is Acid” was licensed for the video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas. He says a producer once told him that Sherman boasted that “This Is Acid” had bought him a Cadillac and a new house. “We were all kids who didn’t know anything about the industry, man, and everybody got screwed over by Larry,” says Joshua. “This could have been still going on and still thriving if everyone wasn’t being greedy.”

In a 1997 Chicago Tribune interview, Sherman all but bragged that he’d taken advantage of the young musicians. “It’s kind of my legacy that the artists have always felt that they didn’t get their fair share of the spoils,” he told Greg Kot. “The kids making these records didn’t know what they should get, and they often didn’t know what their material was worth. And being a good businessman, you don’t say, ‘I think you’re underestimating the worth of your material. Here’s a few thousand dollars more.’ They’d sign away the rights to a song for a few hundred dollars, later it would become a big hit and they’d come running back, ‘Where’s my money?’ ”

Feeling burned by Trax and other companies, many artists tried to do all the record making on their own. They started their own labels and sought their own distributors, but they often struggled to learn the business side and grew disgruntled as an industry with so much promise failed to cohere. Harry Dennis, whose group the It had released songs through Trax, says the house scene “fizzled out” after that. “It’s like crabs trying to crawl out of a barrel,” says Dennis, a plaintiff in the Trax lawsuit. “When it first started off, we were all competing with one another to see who had the best record out.” Then came widespread mistrust of the established labels. “They got all of us against each other.”

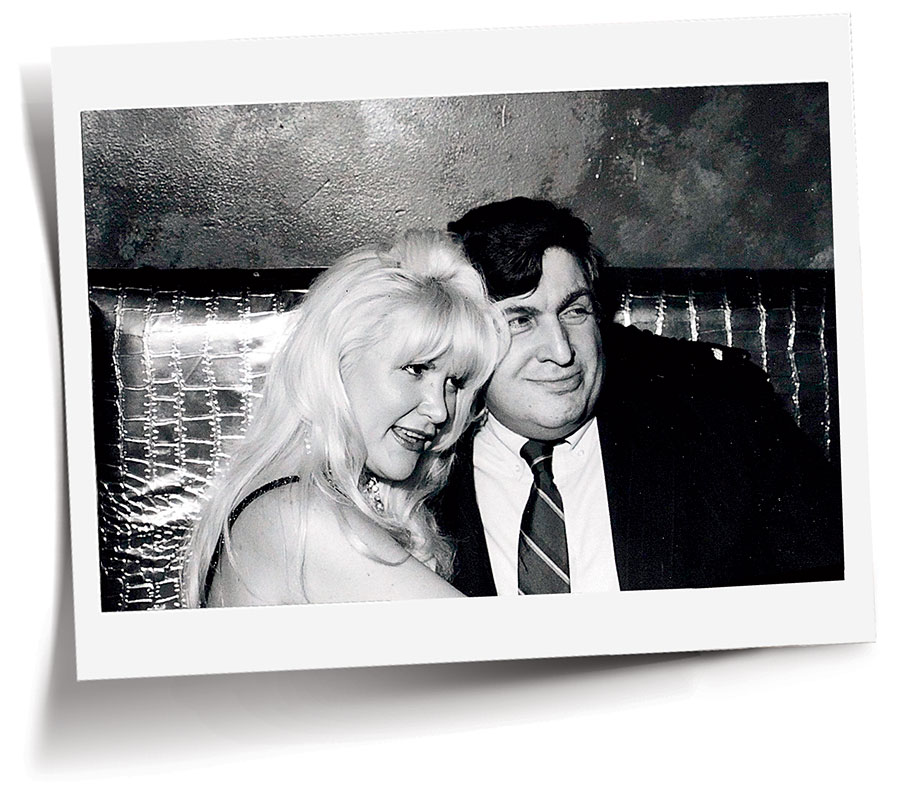

Screamin’ Rachael Cain is a self-described “little dynamo,” a 5-foot-1 platinum blonde with a big nickname and a bigger persona. She grew up in Lincoln Park, fronted a punk band (hence the “Screamin’ ” part), and wound up with another nickname, the Queen of House, which she says was bestowed upon her when she was recording for the German label Teldec.

The road to this queenship began with her singing on Saunders and Lawrence’s “Fantasy.” Soon she had a Trax hit of her own, “My Main Man” (and says she never got paid for it). Then, as she tells it, she signed with Streetwise Records, the New York–based label that also was home to New Edition. She headed east in search of stardom, played club dates, and found a mentor in Sylvia Robinson, who was half of the R&B duo Mickey & Sylvia before cofounding the hip-hop label Sugar Hill Records and producing the landmark singles “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugarhill Gang and “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five.

Cain envisioned emulating Robinson’s performer-producer-executive combination, but in house music, a genre she says was widely disrespected by her New York music contemporaries. She had stayed in touch with Sherman, and when he ran into her while she was performing in Cannes, France, around 1996, she recalls, he urged her to return to Trax.

“I’ll only go back if you make me the president,” she says she told him.

“Why should I do that?” he responded.

“Larry, I’m an artist, and I think I could help you with the artists and make things better for all of us.”

By then Trax had filed for bankruptcy protection, in 1991, after distributors that owed the label a total of $4.5 million reportedly went out of business. In the 1997 Tribune interview, Sherman detailed his plans to reactivate Trax and place Cain at the center of it. Among their projects: Chicago Trax, a three-CD compilation covering the label’s glory years. Sherman told the Tribune that the collection had tallied 150,000 preorders internationally. The money he made from the label, he noted to the paper, continued to pad his bank account, even with Trax dormant. “I would have been perfectly content to pick up a nice big check every few months from sales of the back catalog,” Sherman said, “but Rachael came along and kicked me in the butt, motivated me to get the label going again.”

“I’m really disappointed that people I thought were my friends turned so nasty,” says Trax’s Rachael Cain. “When everybody else gave up, I didn’t. I’m the one who fought for the label.”

But reviving Trax wasn’t as glamorous as Cain expected. “When I came back to Trax, I thought it was going to be a really big deal,” she says. “I get there, the electricity is turned off, the phones are turned off. I thought I was being this fairy princess, and I ended up being Cinderella with the broom. But I still believed in it.”

Although she and Sherman were not a couple when she returned to Chicago to join the label, they married in 1999. She thought of Sherman as “an insane genius” who “recognized this music that other people thought was trash. Nobody understood the music the way he did.” She cites his taking a shot on acid house, which became a phenomenon.

“There was part of me that did fall in love with him,” she says. “Part of it might have been hero worship. Part of it might have been that sometimes I have low self-esteem. I really wanted to save the company, and I believed I could do it.”

But despite her title, she says, Sherman continued running the label and holding the purse strings. “Anybody who knows Larry would know that he was always a controlling person,” Cain says, insisting she had nothing to do with financial dealings or contracts at Trax.

The label released Chicago Trax and other new records, but it was struggling again by 2002, when it entered into a joint venture with Casablanca Media Publishing (a Toronto-based company unrelated to the popular ’70s disco label Casablanca Records), which would administer Trax’s recording and publishing catalog worldwide. According to court documents, Casablanca agreed to advance Sherman and Cain $20,000 each month for expenses — to be recovered from music sale advances — as well as to loan the couple $100,000. When financial disputes arose between Casablanca and Trax, Casablanca successfully sued to dissolve the venture and took sole ownership of the label’s publishing and master recordings, which it then reportedly licensed to a record company in the U.K. in 2007.

Cain’s marriage to Sherman had gone south, too. Cain describes him as “a sociopath.” She shared with Chicago a 2006 letter that she says a Northwestern Memorial Hospital doctor submitted in support of her divorce filing. It attests that she had contended with “multiple types of abuse” in her marriage. The letter also claims that Sherman tried to run Cain over with his car.

In the divorce settlement that followed, Cain received 50 percent ownership of the label. The other half remained with Sherman until he died of heart failure in 2020, when it went to his widow, Sandyee, his partner since 2008. But Cain says it wasn’t until the beginning of 2022 that she was able to extricate Trax from its previous deals and to take control of the label. (Sherman and Cain technically regained ownership of the label in 2012, but it was subject to existing licenses that tied up the catalog, according to lawyer Rick Darke, who has represented Trax since 2006.) Now Cain says she’s working to get the artists paid for their previous work while signing and recording new acts.

The Trax artists participating in the lawsuit aren’t buying it. Lawrence says he discovered that Trax, through one of its deals with another company, was taking a publishing cut of songs he recorded. “I called Rachael and said, ‘Hey, stop friggin’ claiming my songs. You can’t publish my songs like that.’ ” Adds Marshall Jefferson: “She knows she’s not respected by us, and she’s pissed off. So she’ll hold on to the rights to our music with her dying breath.”

But Cain says she has the paperwork to back up Trax’s ownership of disputed songs. And she filed a defamation suit against Sean Mulroney, the lawyer representing Lawrence and other Trax musicians, for claiming, in a cease-and-desist letter to Cain last summer that was circulated more widely, that she committed “fraud” by forging artists’ signatures on contracts. “I think it’s pretty evident I’m really being bullied,” Cain says. “The second Larry died, everyone came after me and attacked me personally. I’m really disappointed that people I thought were my friends turned so nasty. When everybody else gave up, I didn’t. I’m the one who fought for the label.” Without her efforts, she adds, “there would be no Trax Records.”

Cain also disputes Lawrence’s claim that he came up with the label’s name and logo and retains ownership of them. “That’s such bullshit. There’s no proof whatsoever of Vince doing any of that.” Records show she filed to trademark the Trax name and logo in 2007. “All these people were aware of my trademarks for years, and no one has contested any of it.” Says Lawrence of the logo: “She thinks Larry did it?”

Veteran house producer Joe Smooth, who has been working with some of Cain’s recent signees on new Trax recordings, says he respects her moving forward with the label. But he also understands some of the artists’ resentment of her, even if Trax’s revenues were tied up with outside companies until recently. She has, as Smooth notes, lived in a fancy lakefront condo. “There’s been a lot of perks along the way,” he says.

“We didn’t get Russell Simmons or Lyor Cohen,” Lawrence says, referring to the executives who oversaw the growth of Def Jam. “We got these dudes.”

Meanwhile, Sandyee Sherman and her lawyer, Greg Roselli, who used to represent her late husband, are attempting to convince the artists to join them as they push their own vision of Trax. About the only matter on which they and Cain agree is their opposition to Lawrence’s ownership claims. “Vince is kind of coming late to the party,” Sandyee Sherman says. Adds Roselli: “We’re happy to talk to anybody about getting their music back, but we’re not going to give Vince the right to the trademark. We’re going to fight him on that.”

Roselli says that before filing the lawsuit, Lawrence proposed taking ownership of Trax and 40 percent of its content. (Lawrence denies this, saying he insisted only on full ownership of his own copyrights.) “Why would we give 40 percent of the archive to him?” Roselli says. “Because he created it? Worked it? There’s not one document to establish that. And he waited till 40 years later? I don’t understand that claim.”

No matter how much time has passed, Lawrence tells Chicago, as far as he’s concerned, he’s always had a one-third stake in the label: “I never signed anything saying, ‘I’m transferring to you the rights to my [intellectual property].’ ” But he says he has no interest in taking over Trax. “Do I want to run an indie dance label? No. We set out to do something right, do something good. A bunch of people got fucked, and now I’m in a position to help.”

As for why he didn’t go after Trax sooner, while Sherman was still alive, Lawrence has a simple answer: “You don’t sue your uncle.”

His long-ago artistic partner Saunders, who is recovering from a recent stroke, sees things a little differently. He said in an email to Chicago that he joined the lawsuit with a goal that goes beyond getting fairly compensated for his songs. “I would like to regain control [of Trax] and run it properly,” he wrote. Asked if it was his understanding that he and Lawrence each had a third of Trax when it was formed, Saunders replied, “It was Larry and I. Vince drew the logo.”

Trax and local rival label D.J. International never became the house equivalents of Motown and Def Jam. Nor will you find major tourist destinations here, à la the Stax Museum and Sun Studio in Memphis, that inspire house fans to make pilgrimages to the city that birthed this world-shaking music. Visit the site of the iconic Warehouse in the West Loop, and you’ll see a three-story office building.

Lawrence sits at his basement studio console and shakes his head at the waste of it all. “We didn’t get Russell Simmons or Lyor Cohen,” he says, referring to the executives who oversaw the growth of Def Jam. “We got these dudes.”

Yet house remains more than a historical blip. The music has endured and evolved into different forms, such as EDM and amapiano (a South African offshoot), and it continues to inspire some of today’s most popular music: Beyoncé’s latest album, Renaissance, is largely a house record. (Veteran Chicago house DJ Honey Dijon is among its writers and producers.) Drake’s 2022 release, Honestly, Nevermind is also house flavored. Vintage Chicago house recordings remain in demand as well, whether in the form of samples (Kanye West has licensed Trax music) or snippets in video games, movies, and TV shows.

So the stakes of the Trax battle are more than theoretical. “It’s all about a power move and trying to control these intellectual properties,” Joe Smooth, the producer, says. “Nobody really was concerned about the catalog for the last almost 40 years until after Larry passed and these attorneys got involved.”

This isn’t the first legal action against Trax. Two months after Sherman’s death, Larry Heard and Robert Owens, producer-songwriters who performed together as Fingers Inc., sued the label claiming copyright infringement and decades’ worth of nonpayment. The two sides settled last summer, and Heard and Owens regained ownership of their recordings, though they have not yet collected any money, given Trax’s and Cain’s apparent lack of assets.

Maurice Joshua says he would be happy with a similar result for this suit: “It’s time for a lot of the house pioneers that started this sound in Chicago, that started this whole movement in house music, to get their copyrights back, and if there’s money there, they should get some of that too.”

Larry Sherman’s widow says she hopes to settle with Lawrence and the other musicians, rather than fight them in court, so she can proceed with her plans for Trax, which don’t involve Cain. “I really didn’t expect this from Vince,” Sandyee Sherman says. “I hope that going forward he’ll see that I want everybody working together and everyone profiting from it.” Cain sounds a similar note: “I would love for all of us to be able to come together and appreciate our heritage. Tearing Trax apart is not good for Chicago. It’s not good for anyone.”

If a new Trax rises and makes house music viable again, maybe the artists can shake off the weight of what could have been. But for now they’re still fighting to be rewarded for the music that made the rest of the world dance.