Why do some things stick in our memory, while others are completely forgettable? That question is at the heart of research being conducted by the University of Chicago’s Brain Bridge Lab, led by assistant professor Wilma Bainbridge. To answer it, the lab is focusing on art. It has built a machine-learning model called ResMem, which mimics the way we process visual information and can analyze the features of an artwork to predict whether it will be memorable.

In its latest effort, the lab is hosting a contest, in which both amateur and professional artists can submit original pieces. Those works predicted to be most memorable, as well as those thought to be most forgettable, will be displayed April 27 to May 25 at Connect Gallery in Hyde Park and put to the test in surveys of attendees.

Not only does the lab’s research represent an inflection point for artists (Is “memorable” art the only art worth making?), it also has implications in clinical and educational settings.

Isn’t memorable art subjective? Aren’t we drawn to different pieces?

We think we have our unique experiences, but people actually are surprisingly similar in what they remember and forget. Think of the things that determine our memory as a pie. Different slices are your mood at the time, what you’ve seen before, how much you are paying attention, how noisy it is. All these things impact what we remember. We’ve found that the image itself is like half of that pie. Until now, we’ve only seen this using experiments in a lab on a computer screen or using AI models. But research is most exciting when it can apply to the real world. So we thought, When do people see images? When do they want to remember the images that they’re seeing? And that’s when we thought, Oh right, on a visit to an art museum.

How important is it to understand what art is memorable?

You can imagine there’s many different motivations behind an art piece: to deliver some emotion or convey an important message. Or even sometimes just to be beautiful. But I think that for a majority of artists, one of the underlying goals is for their art to be remembered — that beauty or that message or that emotion. Because even if you leave an impression, if it doesn’t last, then it’s sort of like, What’s the point? We all have intuitions about what is memorable, but we found that people’s intuitions correlate very little with what’s actually memorable.

So then how do you determine what makes certain art memorable?

Well, first, we ran an online experiment and found that people tended to remember and forget the same pieces of art. So then we ran a study in person where we had participants go to the Art Institute and do pretty much a freeform visit. We just told them to explore the American art wing, which has like 160-ish pieces. The only thing we asked was that they see every piece at least once. After they stepped out of the exhibit, we had them complete a memory test. What we found is that we could predict what they remembered based on just the pixels in the images. Brightness and color were not related to memorability. Neither were beauty and emotion. Interestingness was a little related.

How do you assess interestingness?

We had a separate group of people online tell us how interesting they thought each piece was, so there was an average interestingness measure. We also found size matters. Larger pieces were easier to remember. But then there’s this other memorability aspect that our neural network [ResMem] picked up on, and we’re finding it’s a pretty complex thing: how efficiently our brains can process the image. So something we can process well easily sticks in our memories because it doesn’t use up tons of resources.

Does that mean art that’s more abstract might be more forgettable?

We haven’t tested it, but that’s my guess. In general, we’re finding that impressionism pieces are less memorable, and our guess is it’s because they’re more fuzzy. Something that’s more clear-cut, with few objects, centrally focused, might be easier to remember. One other surprising finding: Our neural network, even though it didn’t know anything about art or history or culture, could predict what pieces were famous only by their memorability score. In the Art Institute’s collection, for example, Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait scored as incredibly memorable. It could be that if you paint something that’s intrinsically memorable, then that lasts in your memory but also in memory across culture. People are more likely to talk about it. Potentially, famous artists are picking up on some of these subtle differences. That’s one thing we’re interested in looking at with the contest.

What do your findings mean for artists?

It seems like the role of an artist has changed a lot with the boom of social media — like, maybe a lot of art is trying to stick in your memory to get the likes. And one interesting question is: Is this a goal that we should have? Within art, there’s color theory, or how you should do shadowing and highlighting. Maybe there could be memory theory: looking at ways to boost or decrease the memorability of your piece.

What are the implications beyond the art world?

People on the early trajectory for Alzheimer’s disease start to forget some types of images that are memorable to the average person. So we’re finding that those images where people diverge serve as potentially good diagnostic tools. Because you can tell early on that if someone does poorly for this image, that means they’re likely to have a cognitive impairment.

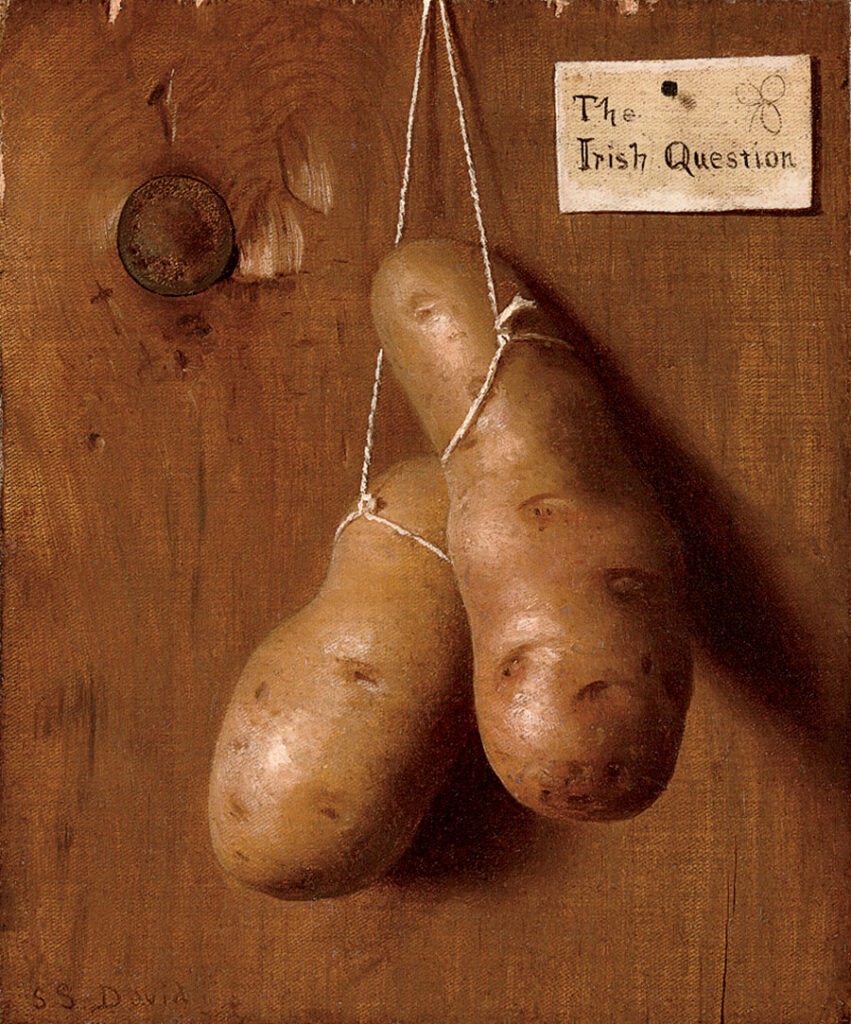

Memorable vs. Forgettable

These four paintings from the Art Institute’s collection scored on the extremes of the Brain Bridge Lab’s memorability scale (represented here from 0 to 100).

HIGHLY MEMORABLE

“Perhaps the clear depiction of a singular central figure makes them easier to process,” says Wilma Bainbridge. “Also, faces are incredibly memorable.”

Jacopo da Empoli’s Portrait of a Noblewoman Dressed in Mourning

90.3

De Scott Evans’s The Irish Question

90.3

HIGHLY FORGETTABLE

“They’re sort of fuzzy, with no central eye-catching object. That might make them harder to process and harder to remember.”

Joshua Cristall’s A Scene Near Lodore, Cumberland

26.8

Joachim Patinir’s Landscape With the Penitent Saint Jerome

24.4