On July 1, 1979, John Belushi flew to Chicago. As a hometown hero and the unrivaled star of a movie in the works based on his and Dan Aykroyd’s Blues Brothers characters from Saturday Night Live, Belushi faced a crucial task: to convince the new mayor to let a film crew tear up her city.

Jane Byrne had taken office that spring as Chicago’s first female mayor. Before Byrne’s ascent, Belushi and Aykroyd would have stood little chance of filming their Chicago car-chase musical in Chicago. Precious few films had shot in the city, a prohibition that dated to the early years of Mayor Richard J. Daley. He had assumed office in 1955 and indulged film and television crews until 1959, when an episode of a now-forgotten series called M Squad portrayed a Chicago cop taking bribes. The city hosted almost no movies for the next two decades, while its urban peers reaped millions in tax dollars and priceless celebrity as cinematic settings: New York with Saturday Night Fever and Manhattan, San Francisco with Dirty Harry, Philadelphia with Rocky, Los Angeles with Chinatown.

“There wasn’t an official policy or anything,” the Chicago Tribune recounted later. “Movies did shoot here. Brian De Palma shot The Fury here [in 1977]. A lot of commercials were shot here. There was even a cottage porn industry in River North. But the cooperation needed for a large-scale Hollywood production — the kind Belushi, Aykroyd and director John Landis had in mind, only bigger — was out of the question.”

Now Daley was gone, and the new mayor had other plans. Byrne had agreed to host the Blues Brothers filming months before the summer shoot. But her power extended only so far. She could allow the crew to drive a convoy across Daley Plaza. She could not permit them to shoot inside the Daley Center itself — that building fell under the county’s purview. Nor could she corral the city’s powerful unions.

Landis had visited Sidney Korshak, an attorney and fixer whose friends included Frank Sinatra, Ronald Reagan, and Lew Wasserman, the Universal studio chief. Korshak had grown up in Chicago and made his name defending Al Capone before pivoting into a prosperous labor practice. His meeting with Landis could open doors that Chicago’s mayor could not.

“I was given his phone number,” Blues Brothers producer Bob Weiss says. “And I was told, ‘If you ever have a real problem in Chicago, call this number. But if you call it, make sure you’ve got a problem.’ He was a heavy, heavy hitter. And not somebody you spoke idly about or to.”

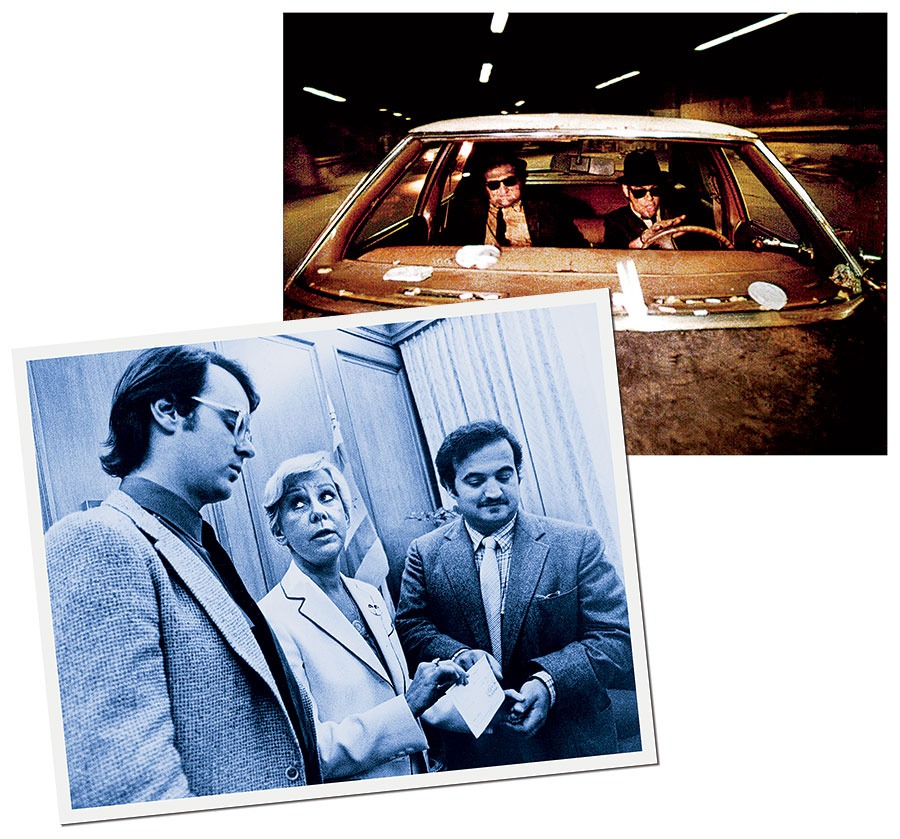

By the time Mayor Byrne summoned Belushi, Landis, Aykroyd, Weiss, and Universal junior executive Sean Daniel to her downtown office, the meeting was pro forma, more photo op than negotiating session. Before signing off on the project, though, Byrne wanted to make the filmmakers sweat.

When the group arrived at City Hall, Belushi was already sweating. “I thought he looked sick, to be honest,” Byrne later told the Tribune. “To the point that his hair was getting wet. I was a fan of his. But, of course, I wasn’t going to say this right away.” She greeted the party as Boss Daley would have, “nodding like Buddha.”

“I know how Chicago feels about movies,” Belushi offered. The mayor nodded. Belushi said the studio wanted to donate money to Chicago orphanages.

“How much money?” the mayor asked.

“Two hundred thousand,” he replied.

She nodded. “So, what’s this movie about?”

“Well, it’s about these two characters, Jake and Elwood, and they’ve got about 10,000 traffic tickets.”

Byrne offered to take care of them. The filmmakers laughed.

“All right,” she said. “If we can’t help you with those tickets, what else can we do for you?”

Belushi kept talking, and talking, and talking. “Finally, I just said, ‘Fine,’ ” Byrne recalled. “But he kept going. So, again I said, ‘Look, I said fine.’ ”

“Wait,” Belushi said. “We also want to drive a car through the lobby of Daley Plaza. Right through the window.”

Daley Plaza’s namesake had died in 1976. Three years later, most of his former cronies had lined up against the new mayor. They called her “crazy broad” and “skinny bitch” and worse. They had owned the city for years and thought they owned it still.

“I wouldn’t have a problem with that,” the mayor replied.

Universal installed most of the Blues Brothers cast and crew at a Holiday Inn. The staff set up a war room inside a downtown production office. They punched through walls to run dozens of cables for extra phone lines to support daily communication with cast and crew, police, and extras. The production would work Tuesdays through Sundays, with most Mondays off, a schedule both punishing and costly: Union workers earned double time on weekends.

Much of the Chicago shoot would play out on Chicago streets and suburban expressways. The script comprised 389 scenes. Starting around scene 72, when Jake and Elwood sped away from a routine traffic stop, the narrative unfolded as one long car chase. Aykroyd had scripted the Bluesmobile as a retired cop car, purchased by Elwood at auction, a detail that honored his fascination with law enforcement and established an ironic camaraderie between the brothers and their police pursuers. Landis reveled in the comic absurdity of 50 new cop cars chasing an old one.

Crew papered the office with maps of Lower Wacker Drive. Crucial chase scenes would be shot along Lower Wacker, beneath the Lake Street L tracks, and on windy stretches of expressway. Several Sundays would be set aside for “lockups,” crew and cops blocking more than one hundred intersections and exits so a stray Sears truck wouldn’t careen into a staged car crash.

Locking up for a single shot required many people and walkie-talkies. Workers designed a light board on one wall map, with little blinking bulbs showing the progress of the Bluesmobile fleeing its police pursuers through downtown Chicago. “It was the first digital electric prop I recall anyone building,” says David Sosna, the assistant director.

In late June, Sosna had driven around the city and suburbs with John Lloyd, the production designer, surveying possible sets. They planned to shoot most of the outdoor scenes in and around Chicago that summer. They beheld Richard J. Daley Plaza, surrounding the county courts building and adorned with a Pablo Picasso statue that they dared not harm. They toured Maxwell Street, home to a famed Sunday flea market, where they planned to film John Lee Hooker’s musical number. They spotted a flophouse on West Van Buren Street, a structure that shook when the L trains passed, a perfect lodging for Elwood Blues. They found a pawnshop on East 47th Street, in Bronzeville, that would serve as backdrop for the Ray Charles number. For the James Brown sermon and song, they located an old Baptist church on East 91st Street, its steeple adorned with a crooked cross.

Location scouts had reported an odd find with cinematic potential: an abandoned shopping mall. Dead malls weren’t so common in the late 1970s, a moment near the peak of the shopping center era. But one Chicago mall had just called it quits: Dixie Square, a victim of crime, vacancies, and blight in the struggling southwest suburb of Harvey. It had opened in 1966 and closed in 1978.

“We got out of the van at the mall,” Sosna recalls. “I remember peeking through a crack, a piece of plywood that was placed over the door.” They gazed upon a dusty warren of empty stores. “I’m standing there with John Lloyd, and John says to me, ‘We can’t show this to Landis.’ We can’t show him the mall because this is too big. They don’t have lights. That means they don’t have electricity. That means we have to put all that stuff in. We were afraid of the cost.”

By the time the crew arrived in Chicago, executives at Universal conceded that The Blues Brothers would cost more than the $5 million that had been budgeted initially. The revised budget, passed down from the studio to the local film commission to the press, now stood at $12 million. Sosna feared even that wouldn’t cover the shoot.

Sosna and Lloyd didn’t breathe a word of their mall find to Landis. But somehow, he found out. He asked his scouts why they were not preparing to film there. They tried to explain their reservations.

“Shut up and show it to me,” Landis said.

The dead mall was perfect. Landis would restore it to life.

On the morning of July 22, a Sunday, 54 Chicago police cars chased the Bluesmobile, a 1974 Dodge Monaco 440, down Lake Shore Drive. The shoot, with stuntmen posing as Jake and Elwood inside the Bluesmobile, ranked as the most ambitious among several preproduction shots — smaller sequences scheduled in the days before the full shoot commenced. Thanks to their deal with the mayor, Landis and company wielded a “control of the freeway that’s impossible to even think about in Los Angeles,” Sosna says. The studio enlisted 76 police officers to drive squad cars and direct traffic, paying them $16.50 an hour and the city $30 a day for each vehicle, plus a full tank of gas.

Weekend motorists found long stretches of Lake Shore Drive and the landlocked Eisenhower Expressway closed to traffic, along with half of the bridges that traversed the Chicago River. Lakefront tenants telephoned the newsroom to report a high-speed chase.

While Landis and Sosna directed police out on the Chicago streets, two giants of R&B — Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin — flew in to record vocals for the big musical numbers that would serve as the beating heart of The Blues Brothers.

By day, Belushi and Aykroyd hung out at the music studio, recording the rest of the Blues Brothers soundtrack with their band. Belushi sang lead vocals on some new songs: Taj Mahal’s “She Caught the Katy,” Steve Winwood’s “Gimme Some Lovin’,” and Solomon Burke’s “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love,” along with the local anthem “Sweet Home Chicago,” the Elvis classic “Jailhouse Rock,” and the Rawhide theme. At night, the boys made the rounds of Chicago blues clubs, hanging and jamming with local talent, including harmonica virtuoso Big Walter Horton and Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson. “They knew what we were up to, and they embraced it,” Aykroyd later recalled. “Any of them that were available, we threw them in the movie.”

When they were done for the night, Belushi and Aykroyd would hail a police car as if it were a cab and catch a ride back to their temporary home, the top floors of the Astor Tower, a modernist Gold Coast high-rise that had hosted the Beatles. Korshak, the powerful lawyer and fixer, had secured them the city’s finest perch.

Soon, the two were drawing thick crowds wherever they went. They faced a dilemma: how to carry on a 24/7 bacchanal while retaining some semblance of anonymity. “There were times when I had the de facto role of bodyguard,” Bob Weiss recalls, “because John would get mobbed and I’d have to get him through and save him from autograph-seekers. There were times when fans would just materialize out of thin air. This was why we had to have the Sneak Joint.”

John Candy, Aykroyd’s old Second City pal, reminded the boys of the Sneak Joint. The Second City cast had haunted the bar, tucked within a yellow coach house across from the theater on Wells Street. They found the shuttered pub and took out a six-month lease at $500 a month. They bought a jukebox and stocked it with R&B singles. They imported a pinball machine and a pool table, polished the old bar fixtures, and reopened the space as the Blues Bar, a private club with oversize portraits of the late Mayor Daley adorning the walls. Steve Beshekas, Belushi’s comedy partner from their youth, came in to tend bar.

“It was glorious good fun,” said Murphy Dunne, keyboardist in the Blues Brothers band. “The police would go in there and claim that they were closing it down, but then it would open up the next night. And Dan, during all of this, made a lot of friends who were cops. He would do ride-alongs. There were rumors the police would go out with Dan, and they would fire automatic weapons.”

August 13, 1979, dawned as a cool, crisp Monday. The first day of full production called for a series of sweeping helicopter shots to establish the gritty gravitas of industrial Chicago. The crew filmed at South Works, a U.S. Steel mill at the mouth of the Calumet River that had billowed smoke across the South Side since the turn of the century. The footage would open the finished film. “We didn’t have drones in those days,” cinematographer Stephen M. Katz says. The camera operator “was hanging out the door of the chopper with a rig.”

Landis had not bothered to ask permission to film at the steel plant, “as we knew they would say no,” he says. As the helicopter hovered, security men emerged from the factory with weapons and opened fire, briefly transforming The Blues Brothers into a war film. Landis ordered a retreat.

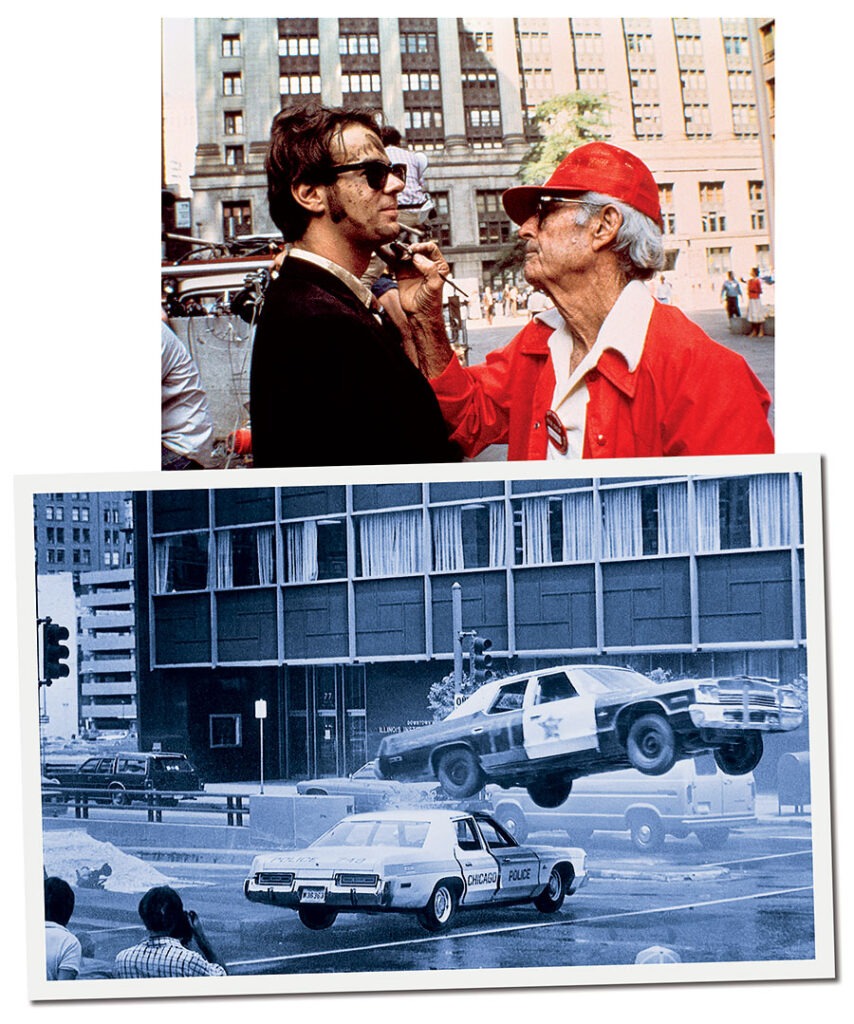

On the first morning of the shoot, Katz vomited. The cinematographer had worked with a tiny crew on The Kentucky Fried Movie, which Landis also directed. Now, he supervised a small army of electricians and grips, and he was scared. “I was a young guy — 29, 30,” he says. “I got saddled with a Universal crew. There were a lot of old-timers, a lot of good old boys, a lot of them had drinking problems, and they weren’t very friendly to me.” Katz is gay. His partner worked on the crew. An undercurrent of homophobia chilled relations with the union men.

For the first big Blues Brothers musical number, on August 16, the crew set up along Maxwell Street, southwest of downtown. Founded by Jewish immigrants in the 19th century, the Maxwell Street Market had evolved into a weekly celebration of Black music and culture. Landis hired hundreds of extras to fill the street, most of them locals. As he prepared to shoot, a police officer assigned to the set bellowed through a megaphone to the crowd, “All right, if anyone fucks up, I’m gonna put them in jail. Do you understand me? You’re going to jail.”

“Hey, wait. What are you talking about?” Landis cried. “They’re going to work for us.”

The officer turned to the director and replied through his megaphone, “You don’t understand these people. We’re not dealing with normal people.”

Landis, his patience exhausted, shouted back sarcastically, “What are we dealing with? Negroes?” The officer backed down.

The scene shows the Bluesmobile creeping through a dense crowd and arriving in front of the Soul Food Cafe, setting up the big Aretha Franklin number inside. Filmmakers didn’t touch the gorgeous neon sign announcing the storefront’s true identity, Nate’s Delicatessen.

As the Bluesmobile pulls up, John Lee Hooker leads a fiery rendition of “Boom Boom” on the street outside, fronting an all-star blues band: Big Walter Horton on harmonica, Pinetop Perkins on piano, Luther Johnson on guitar, Calvin “Fuzz” Jones on bass, Willie “Big Eyes” Smith on drums. That marked an expansive divergence from the script, which called for “two old Black men” playing guitars into little Pignose amps. One of those men was to be Muddy Waters. But a day or two before the shoot, his people notified Landis that the great bluesman had the flu. A doctor was dispatched to examine him, and pronounced that Waters would need two weeks to recover. Alas, The Blues Brothers could not wait. Had Waters been well, “Boom Boom” would have segued into one of Waters’s greats, “Mannish Boy” or “Hoochie Coochie Man” or “Rollin’ Stone.”

Jake and Elwood watch reverentially from outside the diner. Elwood smiles beatifically and says, “Yep,” sounding too verklempt to say more as he takes in the glorious scene, his crazy blues dream made manifest. That exclamation did not appear in the Blues Brothers script: Aykroyd ad-libbed it.

The next day, August 17, the production traveled to the Calumet River, gateway to Chicago’s unsung East Side, to film a spectacular jump across the 95th Street Bridge. In the scene, Elwood vaults the open drawbridge to prove the worth of the new Bluesmobile to a skeptical Jake. A stunt driver executed the jump, driving a Bluesmobile that carried only a gallon of gas, to trim its weight and minimize fire risk. On the first try, the driver “hit with such an impact that the front bumper came off, and it went under the car and it blew out a couple of tires,” crew member Morris Lyda recalls. “It wasn’t a very graceful landing, and Landis just went ballistic.” Lyda was on set with Belushi and Aykroyd to watch. “Dan wouldn’t have missed that for anything.” Landis filmed it again.

“Car’s got a lot of pickup,” Jake deadpans in the filmed scene.

Elwood replies with a classic Aykroyd gearhead soliloquy: “It’s got a cop motor, a 440-cubic-inch plant. It’s got cop tires, cop suspension, cop shocks. It’s a model made before catalytic converters, so it’ll run good on regular gas. Whaddaya say, is it the new Bluesmobile or what?”

“Fix the cigarette lighter,” Jake replies.

Much of the dialogue between Jake and Elwood in the Blues Brothers shoot would play out inside a moving Bluesmobile. To capture it, William B. Kaplan, the soundman, crouched down on the floor of the sedan’s back seat for hours at a time with a tape recorder and microphone.

Once or twice, filmmakers allowed Aykroyd to drive the Bluesmobile at speed. He had street-racer impulses, and that terrified Belushi. Kaplan recorded loud exchanges between driver and passenger, Belushi screaming at Aykroyd to slow down and to ease up on the next turn.

Nearly every Blues Brothers scene would play out to an impromptu audience. Pedestrians and Belushi fans stood and gawked wherever the Blues Brothers crew assembled to shoot. Sometimes, it worked for the film: A high-speed chase down a city street would naturally turn heads. But crowds also gathered to watch Jake and Elwood walk through a doorway. That did not work. Then, the crew would gently ask the throng to retreat behind the police barriers. Sometimes, they refused.

“You can’t really tell people who are walking down the street while you get your shot, ‘You can’t watch our movie,’ ” says Sosna, the assistant director. “ ‘Hey, it’s a public street, asshole.’ ”

At one point, Aykroyd vented to a Tribune reporter: “Every time we try to film, thousands of people appear to watch and foul things up.”

Groupies flocked to the daily Blues Brothers shoot, a steady supply of lovely young women, who sometimes paired off with the young men from the mostly male crew. Someone tacked up posterboard on the side of the grip truck and wrote answers to some obvious questions a visiting fan might ask: the name of the production, its budget, its stars. Drugs? Yes. Availability? Surely.

One night, Belushi donned a hat and sunglasses and headed to a bar with his manager, Bernie Brillstein, an executive producer on the film. The camouflage worked: No one recognized him.

After 15 minutes, he tore off the hat and shades, leapt up, and cried, “Hey! Drinks for everybody!” Then he turned to his manager.

“Hey, Bernie, you got a hundred bucks?”

Production entered its second week. The crew journeyed to Joliet on Tuesday, August 21, to film at the Joliet Correctional Center, a limestone fortress that had once housed Confederate prisoners. Already, delays had pushed the production more than a week behind schedule, but the prison shoot, painstakingly arranged with the warden, could not be moved.

Aykroyd insisted on traveling the 45 miles from Chicago to Joliet by motorcycle. Sosna tried to stop him. “If you crash,” he said, “we won’t have a movie.” Aykroyd appealed to Landis. The director gave his blessing; Aykroyd had ridden thousands of miles on his Harley.

The Blues Brothers production was awash in recreational drugs, so Sosna warned cast and crew not, for heaven’s sake, to bring any to the prison. A couple of grips forgot his instruction. Prison officials found the contraband and sought to jail the offenders. Weiss and Landis talked them out of it.

The Joliet prison housed its share of dangerous men. Between takes, Belushi turned to a guard, gestured to a group of inmates, and asked, “What did those guys do?”

“You see that tall guy?” the guard replied. “He murdered his wife, his two children, his mother and father with a hatchet.”

“Really?” Belushi walked over to the tall convict.

“Hey, is it true you murdered your family with a hatchet?”

“Yes’um.”

“What happened?”

The convict gazed at Belushi. “I don’t know, I just went crazy.”

Belushi walked over to his director. He and Landis gaped at each other and shared a spontaneous “Whoa,” almost as if the cameras were already rolling.

In the film’s opening scene, Jake emerges from the prison through a steel gate that had not moved in 30 years. Landis “paid big money to get that thing opened up,” says Dennis Wolff, the warden at the time. Brilliant sunlight bathes Jake’s body in an unearthly glow.

In keeping with the film’s overarching spirituality, Landis wanted Jake Blues to make his entrance like “an otherworldly, Christlike creature,” Stephen Katz recalls. Landis asked the cinematographer to evoke the blinding light that framed the aliens who emerged from the spaceship in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Sosna found a way to create the effect: The crew placed a giant white curtain behind Belushi and scattered white silica sand on the ground, all to reflect light back at the camera. When they shined 10,000-watt lights on the curtained scene, the white-hot glare rendered the background “bleached out and overexposed,” Katz says. The effect “truly set the tone for the film,” he continues. “It wasn’t based in any reality, more of a spiritual moment. Belushi the messiah had been set free.”

Landis shot the emerging Belushi mostly from behind: Only when Jake and Elwood embrace, six full minutes into the film, would theater patrons see Jake’s face.

Not long after the prison visit, the filmmakers invited the warden and his wife to the Blues Bar. That night, revelers passed around a film can filled with weed. The can reached Jackson Browne, who unwittingly passed it to the warden. “The warden’s holding it, and he’s looking at his wife, and he realizes that he’s holding a can of pot,” says Kaplan, the soundman. “And for a moment, he’s like, ‘Whadda I do now?’ And he just passed it on.”

September 1, a Saturday, kicked off Labor Day weekend. The Blues Brothers production crew set up at Daley Plaza for a three-day shoot that would make its previous efforts look like child’s play.

Seventy-five police officers blocked off the plaza at 7 a.m. Then the troops arrived: more than 200 extras in street clothes, 200 faux National Guardsmen, 100 extras dressed like police, and seven mounted police officers on horseback, playing themselves.

The crew spent the day shooting the end of the car chase, which culminates with the brothers arriving at the courthouse to pay the orphans’ tax bill. “There it is,” Jake yells. Elwood pumps the horn as he steers diagonally across the plaza, scattering pedestrians. The first man to leap away is Landis, in a cameo à la Hitchcock, dressed in a beige camel-hair coat, reprising his stuntman days. The Bluesmobile skirts a subway entrance, narrowly misses the Picasso, and swerves around a roadblock, plowing through a plate-glass window into the Daley Center. It goes straight through the modernist civic skyscraper, scattering more pedestrians, then crashes through another plate-glass window at the far side, emerging onto Randolph Street outside the Greyhound bus terminal. Elwood steers around the corner onto Clark Street, jumps the sidewalk, and hits a no-parking sign, and the car comes to rest outside the Cook County Building at 118 North Clark Street.

“That was the last shot of the day,” Sosna says.

The studio spent $17,000 to replace the shattered nine-by-nine-foot glass panels in the Daley Center, paying union glaziers double time to work on a holiday so the panes would be in place when the city reopened the next day.

After Belushi and Aykroyd exited the battered Bluesmobile, Landis halted filming, and the crew rolled in another Bluesmobile, this one precut into dozens of pieces, stitched back together, and held in place with pins attached to a slender steel cable. A tug of the cable pulled the pins, and the car fell apart. A mechanical-effects operator had toiled for months on the vehicle. A forklift carried it to the set.

Guards watched the collapsible Bluesmobile till morning, when filming resumed. Belushi and Aykroyd found their marks on the sidewalk beside the new Bluesmobile, and the camera rolled. In the scene, Jake and Elwood turn to see the Bluesmobile collapse into pieces behind them. Elwood, stricken by the loss of his mechanical friend, doffs his hat.

The brothers disappear through golden doors into the County Building. An invading army of police and firefighters attack the barricaded doors with axes. The doors were props, replacing the real doors, which the crew had carefully removed.

Cut to Jake and Elwood, jaws set, staring stolidly ahead as the elevator they are in creeps up to the 11th floor, the car silent save for a low pulse of Muzak: “The Girl From Ipanema,” the bossa nova classic.

Back when he was filming Animal House, Landis had asked Antônio Carlos Jobim for permission to parody “The Girl From Ipanema” in a scene that showed Otter dressing for a tryst. Doug Kenney had written funny lyrics. Jobim “didn’t find it funny and said no,” Landis says. In revenge, the director repurposed the song as elevator music in his next film.

All day, the plaza and surrounding streets rattled beneath the combined weight of one Sherman tank, three hook-and-ladder trucks, four troop trucks, 50 squad cars, innumerable army jeeps, one SWAT truck, more than 500 extras, and seven horses. Some in the crew feared the granite plaza might collapse.

Helicopters sliced through the sky. SWAT men crawled across the roof and rappelled down columns. Some of the shaky aerial shots looked like war footage filmed with a handheld camera, which, in fact, they were.

Landis and Weiss had battled with a squeamish Federal Aviation Administration over the helicopters. A DC-10 had crashed on takeoff from O’Hare just four months earlier, killing 273 people. Fearful aviation officials forbade Weiss to land a helicopter on Daley Plaza, restricting him to shooting footage from above. And then, on the morning of the plaza shoot, “I get the invariable 6 a.m. phone call,” Weiss says. A fuel truck had backed into one of the helicopters, rendering it unusable, along with the fixed-camera mount inside. Weiss told Katz that the cinematographer would have to make do without aerial shots.

“I said, ‘Fuck it, take the handheld camera, go up,’ ” Katz recalls. “So, it’s shot with a handheld camera. It’s great, ’cause you feel like you’re really in the helicopter. It reminded me of a Sam Fuller war movie.” Weiss procured a perch atop the Gothic-style First United Methodist Church tower, once Chicago’s tallest structure, to shoot some less shaky footage. (The FAA ended up allowing Weiss to land one of his remaining birds on the plaza.)

The Daley Plaza shoot cost $3.5 million, more than Universal had spent on Animal House, more, reportedly, than any studio had spent on a single scene for any film in a big city. Miraculously, a weekend of pantomimed police actions yielded just two minor injuries. A stuntman tripped while bursting out of an elevator and fell on his foam fire ax. And Belushi strained his back while, as Jake, helping Elwood move furniture to block doors.

The studio spent $17,000 to replace the shattered nine-by-nine-foot glass panels in the Daley Center, paying union glaziers double time to work on a holiday so the panes would be in place when the city reopened the next day.

The studio’s biggest fear had been that someone might land a helicopter on the Picasso, the odd, brooding aardvark whose demise many Chicagoans would have cheered. At one point amid the mayhem, an extra had scaled the statue, prompting Landis to borrow Sosna’s bullhorn and bellow, “Get off of that Picasso,” a line that surely no director had said before nor would utter again.

One hot late-summer day, the crew traveled to Jackson Park, a jewel in the necklace of sprawling urban parks that landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted had planted around Chicago. Atop a historic Jackson Park bridge, they staged a demonstration by Illinois Nazis.

By introducing white supremacists into The Blues Brothers, Aykroyd and Landis fed the film’s narrative arc, the plot-driving “mission from God.” The Nazis served as a symbol of entrenched American racism, which every great Black musical artist had battled. Yes, the brothers had legions of police and troopers and chagrined country-and-western musicians who tried to thwart their quest. But only the Nazis, alone among the their pursuers, counted as truly villainous.

“We had always intended to have some sort of white-supremacist thing,” Landis says. “The Klan, we couldn’t use them, because it was Chicago,” not the South. Instead, Landis chose Nazis. And if the notion of a Catholic orphanage owing property taxes sounded far-fetched, the idea of neo-Nazis marching in Chicago did not. They had planned a demonstration for the summer of 1978 in the largely Jewish suburb of Skokie. Amid howls of outrage, officials moved the rally downtown, where Chicagoans pelted the Nazis with eggs.

Now, Landis re-created the standoff in verdant Jackson Park, a dozen faux fascists facing scores of screaming protesters. He recruited Henry Gibson, a former Laugh-In regular who had appeared in The Kentucky Fried Movie, as their leader. Landis wrote a speech for Gibson to deliver to the frothing crowd, larded with lines such as “the swastika is calling you.” He transcribed the words verbatim from the answering-machine message of the real-life National Socialist Party of America, the group that had assembled in Chicago.

Before the cameras rolled, Gibson told Landis, “I want to speak to the crowd.” He addressed the throng of extras: “I’m a nice guy. I don’t mean any of the things I’m going to say.”

The scene starts with the Bluesmobile stalled in traffic at the stone bridge.

“Hey, what’s going on?” Jake asks a passing cop.

“Ah, those bums won their court case, so they’re marching today.”

“What bums?”

“The fucking Nazi party.”

The line in the script contained no expletive. The cop added it on his own. Landis kept it.

Elwood scoffs. “Illinois Nazis.”

After a considered pause, Jake replies, “I hate Illinois Nazis.”

Elwood screeches the Bluesmobile around the traffic jam and up the bridge, scattering Nazis into the lagoon, to ecstatic cheers from the protesters. Crew workers tossed dead fish into the water to float among the thrashing Nazis in their close-up.

At times, during those long weeks in Chicago, the Blues Brothers shoot came to resemble a montage of car crashes. In addition to renting active police cars for chases, the Blues Brothers crew purchased more than 60 retired squad cars, at $400 each, for crashes. Every night, after a pileup, “the teamsters would be there with car carriers, and they would haul the cars that we had damaged back to a garage on the West Side of Chicago, a garage that was in a nasty neighborhood where people got shot,” Sosna says. Repairs to the fleet would allow The Blues Brothers to set a record for cars destroyed in a film: 103.

The L track chase ends in an epic pileup. As the scene unfolded, cinematographer Stephen M. Katz turned to a visiting Universal executive and said, “I’ve always wanted to make an art film.”

The crew filmed many crash scenes on Sundays, when expressway traffic ran lighter. One Sunday, during filming in the western suburbs, an inconvenienced motorist “took his car, and he tried to run over a lady cop” at a freeway entrance, Sosna recalls. “So, the lady cop says on the radio, ‘This guy’s trying to kill me with his car.’ And at that moment, I lose control of the set.” The imperiled officer’s comrades took off in their squad cars, “going the wrong way on the freeway,” a scene as crazy as anything in The Blues Brothers. Officers swarmed the aggressive motorist and “beat the fuck out of this guy.” Then they returned to their positions, and filming resumed.

For one particularly daring sequence, to be shot over three days, the schedule dictated: “100 mph chase under El tracks.” Mayor Byrne had granted filmmakers permission to shoot 30 cop cars chasing the Bluesmobile along Lake Street, a catacomb of trestles supporting elevated tracks, at racecar speeds. Sosna locked up every intersection and cleared the sidewalks beneath the tracks before shooting the breakneck pursuit. Stunt drivers replaced Aykroyd and Belushi, whose close-up images would be spliced in later.

In the scene, Elwood steers the Bluesmobile through one calamitous intersection after another, running red lights, swerving around a panel truck, evading station wagons and even a pack of cyclists. The absurd procession of obstacles looked like something out of The Kentucky Fried Movie. Landis had pumped the crew for suggestions.

He loved the idea of the Bluesmobile blowing past bicycles. Sosna hated it. “Somebody’s an eighth of a second late, he’s gonna be dead,” he fretted.

Landis himself rode in the “Bullitt car,” a stripped-down Corvette with a camera mounted on top, designed for filming the Steve McQueen movie, “going 110 mph with the stunt driver and talking into the walkie-talkie, cuing the trucks and the bicycles,” the director says. “It was all done in one long take.” He filmed Belushi and Aykroyd in a separate run at a much lower speed, shooting backward from a camera car that towed the Bluesmobile.

The L track chase ends in an epic pileup. The Bluesmobile hits a stopped cruiser. More cop cars hurtle into the scene, crashing into each other, flipping dramatically and launching off one another.

“We had to get permission from the city to drill holes in their streets so pipe ramps could be bolted into the street,” Sosna says. The pipe ramp, a piece of stunt-car technology, flipped a car on its axis if hit at the right angle. The ramp worked so well that the finished scene shows cars entering the frame already airborne and upside down. Filmgoers had never seen the like.

The final smashup “took a hell of a lot of planning,” Katz recalls. “I’m standing on the sidelines watching this. All the cameras are rolling, and I’m just hoping there’s film in the cameras.” As the scene unfolded, Katz turned to a visiting Universal executive and said, “I’ve always wanted to make an art film.”

Most interior shots for The Blues Brothers would wait until the crew reached Los Angeles. But the location scouts wanted to film inside the flophouse at 22 West Van Buren Street. They repurposed it as the Plymouth Hotel, home to Elwood’s one-room apartment on the L tracks in the Loop.

“Well, it ain’t much, but it’s home,” Elwood announces in the scene as the pair enters the pistachio-walled room, a space almost too slender for a single bed.

“How often does the train go by?” Jake asks.

“So often you won’t even notice it.”

Elwood puts a record on the turntable. He toasts Wonder bread on a bent clothes hanger over a hot plate. Jake falls asleep on the bed as the ceaseless trains roll past, visibly rattling the room.

Landis wanted the apartment scene to play out against a constant rumble of passing trains. Outside the window lay parallel tracks, enclosing the city center within a rectangular loop of elevated railway.

Sosna paid four motormen to sit at either end of each two-car L train and run them in opposite directions. “On the foreground track I had one train, and it would go right to left. And a second later, there’d be a car going left to right” on the other track, he says. “And then both cars would stop, and they’d reverse.” All this played out during a late-night lull in transit service. The scene defied reality: Even at rush hour, L trains never pass quite that often.

Belushi had appeared healthy at the start of shooting. By the time of the nocturnal flophouse scene, he looked pale and sounded stuffy, the toll of relentless partying. The decision to conceal the boys’ eyes behind dark sunglasses suddenly looked providential.