They were dancing wildly that night at Latham House, the decrepit dorm at the southern end of Northwestern University’s Evanston campus. The structure, an old three-story dwelling where George McGovern had lived as a history major in the 1940s and where 42 young men now resided, was to be demolished, as I was told by the social chairman, because the building was long past its expiration date. Such was his story anyway when hiring us, and it sounded reasonable. But reason disappeared once the Del-Crustaceans started up. If you’ve ever played at a demolition party, you’ll know what I’m talking about: People get giddy and the wildest in the crowd take over. Which is good. Good for rock ’n’ roll.

As we blasted into “Louie Louie” and “Gloria” — three chords each, of course — there were kids slinging furniture and bashing holes in the plaster walls and breaking everything in sight with hammers and lamps and garbage cans. It was transcendent to be in the middle of the mayhem, screaming choruses into a mic — “GLORRRRR-EEH-UH!” — and setting the tone for the joyful and idiotic primal release.

The louder we played, the more fun the crowd had. The more fun they had, the more the walls splintered. In the basement, we would learn later, somebody had been working on the main support beams with an ax or saw, perhaps to get the building to collapse completely, like a rabbit into a top hat, and we wondered if that was the thudding we’d felt, which we had assumed was just people jumping up and down.

That gig, I’ve always been convinced, was when we Dels made our bones, proved something to ourselves. We were into wild parties. And wild parties, we now knew, were into us. All we ever wanted to be was a party band, to do it properly. We didn’t write songs. The best ones had already been written. We didn’t want to make it to the top of the charts. The only mountain we wanted to climb was the mountain of fun, to be the Sir Edmund Hillarys of good times.

But the good cheer of the Latham House party was short-lived. The next day we found out the dorm had never been scheduled for destruction but was merely going to be sold by Northwestern at the end of the school year. Oh boy. A headline in the Sun-Times said, “ ‘Last Blast’ Clears Dorm.” The front page of the Daily News stated ominously, “Dorm Bash Riles NU Brass.” The building was declared unsafe for habitation. Student residents were evacuated. Some were in deep doo-doo. We were seriously worried at first — were we liable? — but then oddly encouraged. We were recently out of college, mere visitors, and, as we would learn — since no one overtly blamed us for the carnage — beyond the law. We were free, full of energy, ready to rock. We’d made $150 for the night, and we knew we’d never stop. The point is that this was 1972, more than half a century ago, and we haven’t stopped.

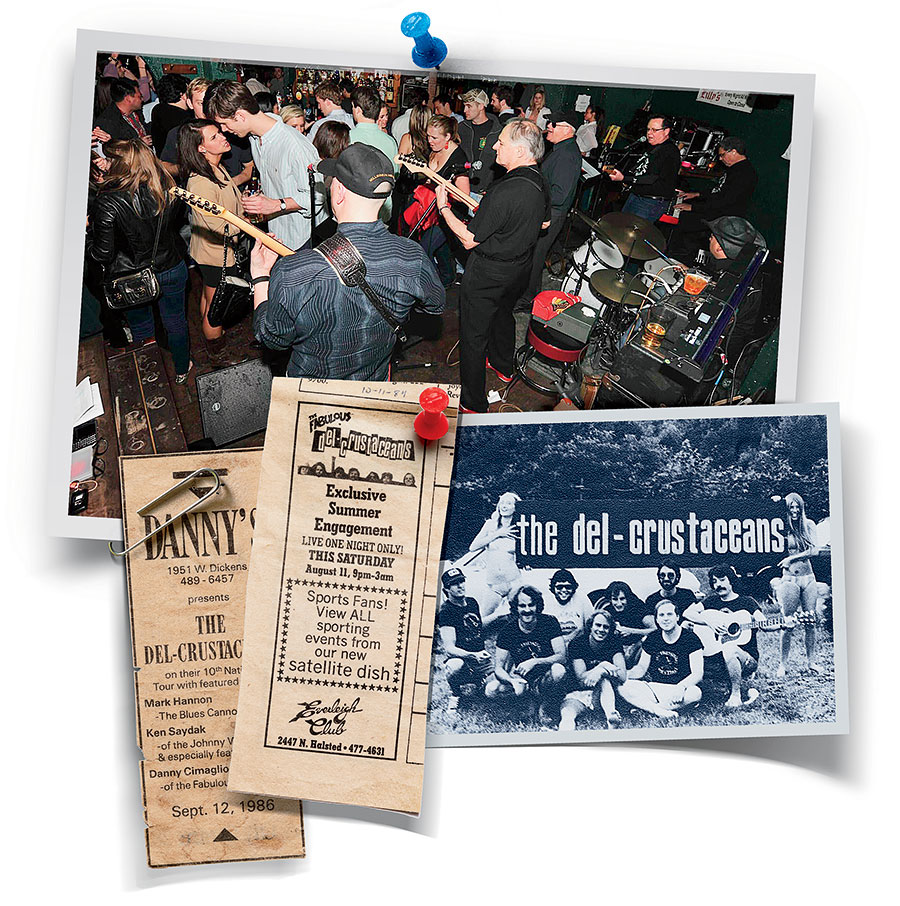

It’s hard to say how many gigs we’ve played through the years, but it’s in the many hundreds. We’ve peaked and ebbed a couple of times, members have come and gone for various reasons, almost always because of moving elsewhere. Early on we went through drummers like lint through a dryer vent, but we’ve carried on. Through it all, we’ve had, as the band saying goes, “day jobs.” I became a writer for Sports Illustrated and finally a sports columnist for the Sun-Times, while also writing books. Other guys worked as everything from a karate teacher to a structural engineer. Ron Berler, one of the earliest band members, was a writer like me, with his claim to fame being the discovery of the Ex-Cubs Factor, a fascinating theorem that stated — correctly for years as nonsense would have it — that no Major League Baseball team with two or more ex-Cubs on it could win the World Series. But whatever we did for a living, none of it changed our desire to rock on.

We’ve played at countless weddings, including all our own. We’ve played in garages, in backyards, in tents, in seedy hillbilly bars, in swinging hipster bars, on a barge in Manhattan’s East River, in the lobby of a bank in a downtown high-rise, and at more country clubs than you can name. We’ve played at the Shedd Aquarium, Wrigley Field, Navy Pier’s Grand Ballroom, the Playboy Club in Lake Geneva, the Playboy Mansion on the Gold Coast (loved that poolside Woo Grotto), and the crazed Bull & Whistle in Key West, from which we were fired after three nights of our four-day residence back in 1978, since we’d written our contract on a napkin, and the napkin disappeared or something, I can’t recall. There’s a bunch that I can’t recall. But I do know that almost all of the songs we play now are the same ones we played at the start. They were good then, they’re good yet. Can you top “La Bamba” or “In the Midnight Hour”? Don’t think so.

We’d formed in the spring of 1971, one year before that demolition ball, when I met Robert “Bo” Van Sant and Paul “Pablo” Lundberg in a poetry class at Northwestern in the final quarter of our senior year. As we would drunkenly sing doo-wop songs and Ricky Nelson ditties on the front porch of the large Asbury Street duplex where I lived with 10 to 15 other guys (you never knew who might be staying), playing badly on cheap guitars, the idea of a band gradually entered our dreamy, often-addled brains. Actually, for Van Sant, it might have been his junior or even sophomore year, since he had dropped out a year or so earlier, was immediately drafted into the army, and had just come back from a horrific but darkly humorous combat stint in Vietnam. That episode did not do him any good, and his hell-with-it-all party attitude became the default philosophy of the young Del-Crustaceans.

That summer we added a couple of friends to our new venture, this alleged band, which had yet to play anywhere or have a set list or electrified equipment. First we brought in Tom “Gabby” Gavin, who played bass in the Beta Theta Pi fraternity band. Then we added Berler, whom we knew from Chicken Unknown, an absurdist trio that had recently played, or rather screamed, at a party in the front room of our duplex for $10. He joined Bo on lead vocals. We did have a name, which came together for Bo and me after a night of strenuous, alcohol-fueled front-porch singing. There were bands with weird monikers back then like Strawberry Alarm Clock and Crazy Elephant. But we felt more in tune with Dick Dale & His Del-Tones and the Delfonics and the Del-Vikings. And then there were the Ovations, the Temptations, the Hesitations, even a ’60s gospel group called the Inspirations. “Del” and “Crustaceans” was our synthesis. Soon we painted “Mighty Mighty Del-Crustaceans” on the wall of Graceland Cemetery facing the L, a carefully crafted bit of graffiti we’d later find out was believed by commuters and city officials to be the name of a new street gang. We also painted our name in Day-Glo pink on a four-by-eight-foot piece of plywood mounted on wooden stands and lit by black light bulbs, all of which we intended to carry to every gig and set up behind us. Which we did.

Back to personnel. At last we found a drummer who didn’t disappear on us: the excitable Jack Lau, who kept the beat we needed and loved fun times as much as we did. He played with his sticks reversed, creating a snare drum rimshot blast so sharp and tom-toms so deafening that I wear hearing aids now largely because of that. Drew Hannah, a quality guitarist, joined from a band called Lucky Mud, and we added Mike McDonnell, bearded and calm and philosophical, on keyboards. Peter “Coach” Johnson, a.k.a. the Dancing Codpiece, stepped aboard as our hybrid singer-“dancer,” and though he’s now a distinguished business professor at Fordham University, to me he’s still the guy who sings behind mirrored shades and kneels down at the end of “Stand by Me,” overwhelmed with emotion as we drape a cape over his shoulders and gently lead him offstage, à la James Brown and his handlers.

When I say the 54 years of playing in this band have flown by, I’m not just resorting to cliché. I mean it. I just turned 76. I often say I still feel like a 22-year-old but one who’s been in a fight. And yet time for an old rock band moves in both directions, hands on the clock crisscrossing with memories and visions of the future, wrapped in music. All those gigs in so many places. Like in 2010, when we played with blues legend Lonnie Brooks at a Wrigleyville bar, backing him on “Hey Bartender” and “Sweet Home Chicago.” Bill Murray showed up in 2008 to sing “Honky Tonk Women” and “Hang On Sloopy” with us at the Cubby Bear. At Lilly’s on North Lincoln we played nine straight New Year’s Eves, from 2010 to 2018, and a couple of times cast members from Million Dollar Quartet, playing at the nearby Apollo Theater, stopped in to sing Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis songs with us. We sometimes would play from 8 p.m. until the 2 a.m. closing time. Your hand would cramp, your back would ache, your voice would crack, but the last thing you wanted to do was stop. The joy might end, and the dancers out front might never return, and the moment, like a shout down a busy street, might vanish as if it never were.

Time for an old rock band moves in both directions, hands on the clock crisscrossing with memories and visions of the future, wrapped in music.

It was the simplicity of the early rockers that motivated us, those of the late ’50s and early ’60s whose tunes had only a few chords that an untalented but enthusiastic guy like me could copy. Catching shows in Chicago, at the Quiet Knight and blues clubs like Theresa’s Lounge and the Checkerboard Lounge on the South Side and at Kingston Mines and B.L.U.E.S. on the North Side, was a first-rate education. Among the lessons: that a Fender Reverb is a great amp, that a Stratocaster is worth spending 600 bucks on, that Shure microphones are dependable even after a beer shower. I learned how to play “Matchbox” by standing three feet in front of Carl Perkins at Biddy Mulligan’s on Sheridan Road, just off Howard Street, with hardly anybody else in attendance — studying his every motion, the way he hit the open A chord and then the low E string for rhythm, and I could see the messed-up finger on his left hand, the one he told us he’d stuck in an electric fan.

At our most impressionable time there were, of course, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Beach Boys — performers not a whole lot older than us who were in real bands they formed themselves, not fake ones created by producers or agents. They wrote their own music, played their own instruments. We loved them because they were brothers in sound. Geniuses, of course. But pals, always. They inspired us mightily, made us want to be like them, at least on Saturday nights at graduation parties and bar bashes.

We started at the bottom, naturally, performing for maybe six people in a YMCA basement, which I believe was our first paying gig. In time we played for huge crowds at the World’s Largest Block Party at Old St. Patrick’s Church and at a lunatic series of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations at the old Germania Club. Those late-’70s dancing frenzies in that cavernous club, with the twisting, two-story marble columns flanking the stage and an enormous ceramic mural titled The Glory of Germania looming behind, felt like revisits to our seminal Latham House demolition party but without the drywall dust. The bashes were hosted by a young John Cullerton, future Illinois Senate president, and a couple of his pals.

Could the Dels really have had top billing at a black-tie holiday party at the Drake, rushing the famed orchestra in front of us off the stage so we could get the party bomb lit? Yes. How about playing at Stubb’s Museum Bar in tiny Ontonagon, Michigan, hard by Lake Superior, during deer season, with the weather so cold the carcasses strapped to the hoods in the parking lot were stiff as iron? Yes, that too. We weren’t trying for celebritydom. We wanted normal but musical lives with the bond of equals, the whole that’s greater than the parts.

I look at the small notebook I’ve jotted in sporadically through the years, keeping track of gigs, pay, costume changes, musical observations. I spot hints of the 15 or so guys (counting all the early disappearing drummers) who have at some time or other called themselves mighty Del-Crustaceans. The notebook is, in its way, a journal of my adult life. I turn the pages and the year 1983 appears. Randomly: “March 12, Chris Nielsen party — Chris shows ‘The Buddy Holly Story,’ distributes Pearl Beer.” “March 26, Kirkland & Ellis law firm, Saddle & Cycle Club — $1,500 + $400 overtime.” “May 20, NU Law School, Knickerbocker Hotel, lighted dance floor.” “June 18, Park West, Rugby Ball — Jack unveils new paint job on drums.” “July 22, house party thrown by roadie Brett Gitskin, $350, favor for hard-working veteran equipment lugger. Very hot. Dels go barechested for first time.” “July 23, Henrotin Hospital charity ball, Saddle & Cycle. Dels sport Speedos for first time. Picked up with socks, wristbands at Sportmart. Audience is stunned.”

So much to sift. Playing with my son, Zack, now a 34-year-old singer-songwriter in Austin, Texas, has been a resounding joy. Listening to the cornball jokes of our beloved drummer, Mike Gassman, a pal for over four decades, is still a hoot. (Example: “What do you call a drummer without a girlfriend? Homeless.”) And then there are the wonderful former roadies of ours — the aforementioned Brett Gitskin, along with Troy Blaisdell, Dan Icenogle, and Cody “The Roadie” Festerling. No longer students, now all grown — the first a businessman, the second a retired bigtime roadie (Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, Brian Wilson, Celine Dion, etc.), the third a Wisconsin lawyer and doctor, and the last a gentle teacher and career Peace Corps volunteer now in his sixth country, Kosovo.

And yes, in our 54 years we’ve had band members die. The hard-living Van Sant succumbed to a heart attack in 1986 at age 37. Lau, who had moved to Hawaii, suffered a stroke and died five years ago. Bass player Dave Bradshaw died of pancreatic cancer in 2008. I talked to Dave on the phone from Evanston Hospital just before he passed. “Tell everybody I had the rock ’n’ roll spirit,” he said. I still do. His place in the band was assumed first by Fred Koch, a longtime Lake Bluff friend from the Hellhounds, and now by Giray Emsun, the pride of Antioch.

When are you going to stop?” people ask us. Why would we? The end will come when it wants, indifferent to our whims, with the deep silence of forever.

COVID was a gut punch to everything the Dels love. For over two years we didn’t play at all. But by 2023 we got active again, spurred on, as usual, by lead guitarist Ron Stein, who joined a quarter century ago and always pushes us to get out and go. And we do.

But then we took another unanticipated break after playing a high school reunion in Peoria late last summer. Brian Mott, our skilled pianist and soulful singer — his “Unchain My Heart” could make you turn your head and marvel — called a few days beforehand to tell us how much he wanted to play but that he had to bow out. He’d been fighting bladder cancer for over six years, we knew. At a job in Evanston, I’d asked him why he wasn’t drinking anything but water and he’d told me he was toward the end of a fast to help starve the cancer cells. “How long since you’ve eaten?” I asked.

“Two weeks so far,” he said.

We’ve got a new gig coming up soon, a smaller one with mainly old friends down in my basement, a good high-ceilinged space where the equipment is always set up in front of the sound-deadening Autumn Plum velvet curtains (the catalog description, not mine), the modern blue-and-white electric Del-Crustaceans sign behind us (“Est. 1971”) and photos of the band through the years hung all around.

Brian won’t be with us. His wife, Cathy, will drive in from Madison. A couple of us visited Brian up there after that Peoria gig. He had said to come quickly since he was done taking chemo and hassling with any of that crap, and he’d been told he would likely get a little goofy as his liver failed, maybe not remember too much. We came and sat in his living room, the heat way up because he felt chilled, the way cancer patients often do, and he said he’d had a good life, was at peace. And then he rose weakly from the prone position, his skin already turning a flaxen pastel, closed his eyes, and once more belted out “Stormy Monday” as Stein played the bluesy guitar chords on the acoustic he’d brought along.

Brian’s now with our other bandmates who left the stage early. In their way, they all said goodbye and to keep rockin’, knowing we’d be trailing along when our songs were done, too. I hugged Brian one last time, trying not to cry, and said, “I’ll see you soon enough, my friend.” He smiled and answered, “They say time doesn’t exist up there.”

Now it was my turn to smile. At least I think I smiled.

“Right away, then,” I said. Right away.

Just a few more gigs is all.