1 Black baseball in Chicago dates back to the mid-19th century.

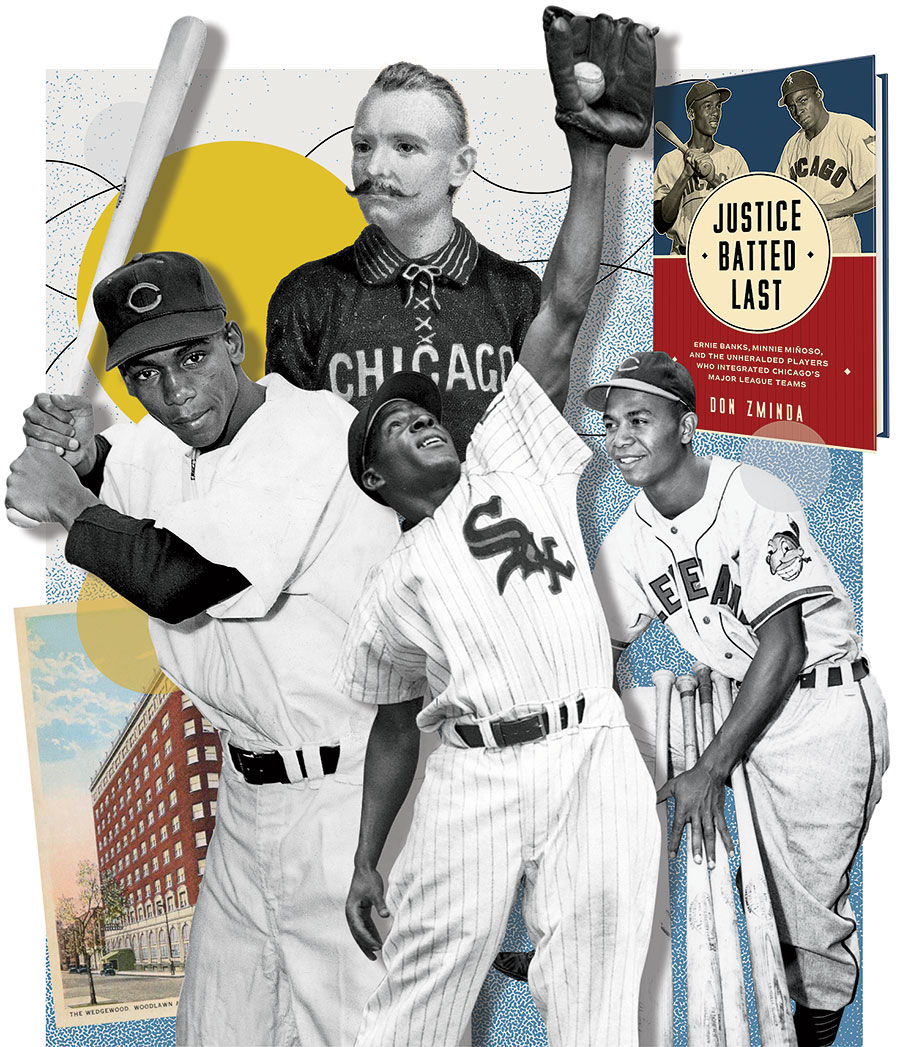

“The most notable of the early teams, the Chicago Blue Stockings, played and often beat white opponents during the 1870s, though they were denied admission to the state’s Senior Amateur Championship tournament,” baseball historian Don Zminda writes in Justice Batted Last: Ernie Banks, Minnie Miñoso, and the Unheralded Players Who Integrated Chicago’s Major League Teams. The Chicago Unions, formed in the late 1880s, “dominated the amateur baseball scene in Chicago,” he quotes historian Leslie Heaphy as saying, and in 1895 they took two of three games from one of the city’s best white semipro teams.

2 A couple of Chicagoans played a key part in keeping Blacks out of the majors.

Cap Anson, the superstar player-manager of the Chicago White Stockings, the precursor to the Cubs, threatened to not let his team play a Toledo squad that had a Black catcher, Moses Fleetwood Walker. Walker, one of the few players of color in white organized baseball at the time, was forced to sit out the game. Anson later helped derail attempts by the New York Giants to sign Walker and another Black player. There wasn’t another Black player in the white major leagues for 63 years, until Jackie Robinson in 1947. That absence was in no small part because of the influence of Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who had been a Chicago federal judge. Though Landis stated publicly that there was no rule that a player be white, the color line was strictly enforced during his time as baseball commissioner, from 1920 to his death in 1944.

3 An East Hyde Park hotel refused to lodge the American League’s first Black player.

When Cleveland’s Larry Doby made his historic debut in July 1947, for a game in Chicago against the White Sox, he wasn’t allowed to stay with his teammates at the stylish Hotel Del Prado, in what was then an almost exclusively white area. “The Indians had to scramble to find a ‘Black hotel’ for Doby,” Zminda writes. One place in town that catered to Black athletes, including boxing champ Joe Louis, was Woodlawn’s Wedgewood Hotel, partly owned by track legend Jesse Owens. It later served as the residence of the White Sox’s Minnie Miñoso.

4 Minnie Miñoso ended up on the White Sox because he had been on a team said to have too many Black players.

Miñoso, the first Black player for either of the Chicago teams, was originally signed by Cleveland in 1948, but the general manager of the White Sox, Frank Lane, was able to obtain him in a trade in 1951 because the Indians were too integrated. “The Indians can’t keep Miñoso,” an anonymous major-league executive told the Cleveland Plain Dealer at the time. “They’ve got all the colored players they can handle.”

5 The Cubs signed a Black player before the Sox did but took longer to integrate their major-league roster.

In 1949, the Cubs assigned Charles Pope, a catcher from San Francisco, to their low-level minor-league affiliate in Visalia, California. But despite hitting a respectable .286, Pope was released that June and never played in the big leagues. Not until 1953 did the Cubs integrate their major-league roster by signing Ernie Banks out of the Negro Leagues and calling up Gene Baker, who had languished in the minors for four seasons. Banks played his first game September 17, three days before Baker, who was recovering from an injury.