On a February Saturday in Little Village, several hundred people gathered in the numbing cold to protest the Trump administration’s targeting of Chicago and its immigrant communities. Incidents of federal agents in unmarked cars pulling up to take undocumented residents away and a Justice Department lawsuit trying to force the city and state to cooperate in such raids were generating growing terror in Latino neighborhoods. The ralliers hoisted signs that read “No Mass Deportations,” “Fuera ICE,” and “Trump: Somos Trabajadores, No Delincuentes” (Trump: We Are Workers, Not Criminals).

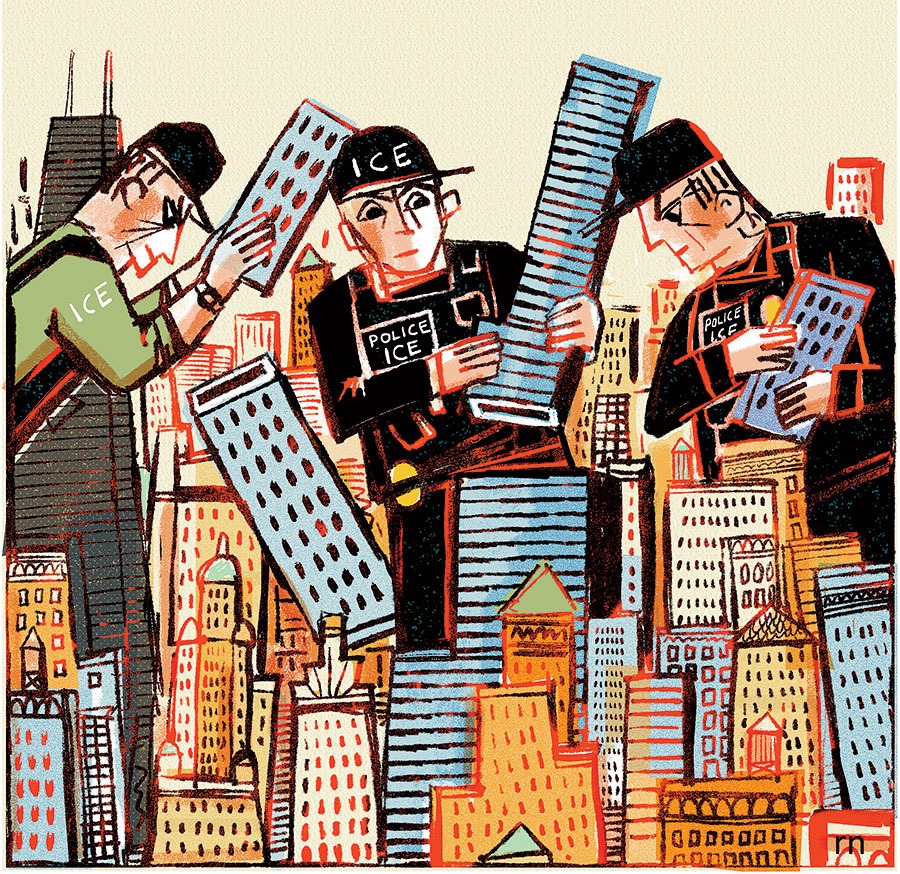

Chicago bills itself as a “sanctuary city” for undocumented immigrants, with rules that prohibit local officials from assisting in federal deportation efforts. Mayor Harold Washington first designated Chicago as one in 1985, and the policy has been amended and strengthened since, most significantly in 2012, when it was codified as the Welcoming City Ordinance. Among other things, Chicago police are largely restricted from helping U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement identify, arrest, or remove undocumented immigrants. Chicago’s policies have long drawn fierce criticism from conservatives, not least during last week’s brutal Congressional grilling of Brandon Johnson and other prominent sanctuary city mayors by the House Oversight Committee.

But many immigrant advocates believe the term “sanctuary” is inaccurate and counterproductive, overstating what the law actually does and making the city a target for what President Donald Trump is vowing will be “the largest deportation program of criminals” in U.S. history. “The Trump administration is leaning on that term to suggest that Chicago is harboring or somehow blocking ICE from doing its enforcement, and that’s just not how these laws operate,” says Mark Fleming, who, as associate director of litigation at the National Immigrant Justice Center, helped write and defend such legislation.

Under Chicago’s Welcoming City law, local officials aren’t allowed to inquire about or investigate a person’s immigration status, at least in most cases. Police also can’t arrest or detain someone solely for being in the country illegally. ICE is still free to conduct immigration enforcement in the city, and the ordinance does not stop Chicago police from cooperating with the agency in criminal matters, such as when a judge issues a criminal warrant. The way ICE typically operates, it asks local law enforcement around the country to detain those suspected of violating civil immigration laws for up to 48 hours beyond their scheduled release, which gives federal agents time to pick them up. Chicago refuses to participate in this practice.

“The federal government doesn’t have any authority to command local subnational governments to assist with its own agenda, and if they do, that’s called commandeering,” says Martha Davis, a constitutional law professor at Northeastern University. Adds Fleming: “The nonparticipation laws by state and local law enforcement do present real protections.”

Many immigrant advocates believe the term “sanctuary” is inaccurate and counterproductive, overstating what the law does and making the city a target.

That’s partly because of manpower. ICE has only a few thousand deputized agents across the country. In a show of force earlier this year, ICE agents, joined by other federal officers, rounded up about 100 people in Chicago and delivered them to detention centers. If Trump intends to follow through on his threat to carry out mass deportations — what could amount to tens of thousands of Chicago residents — he’ll need more boots on the ground. Trump has brought up deploying federal troops in cities, ostensibly by invoking the Insurrection Act of 1807, but that would be an extreme measure.

If Chicago were in a Republican-dominated state, it might be a “welcoming city” in name only. States legally have far more authority over their own municipalities than the federal government does. But Chicago’s policies are bolstered by the 2017 Illinois Trust Act, which also prohibits state operators from collaborating with ICE.

That isn’t to say Chicago’s bulwarks are impenetrable. ICE, for instance, can identify some undocumented immigrants here through law enforcement backchannels. When Chicago police officers make an arrest, they upload fingerprints to an FBI database to check for outstanding warrants and criminal history. A 2008 law gave ICE full access to FBI data, and it can match the fingerprints with any immigration records in its own system and use that information to make arrests.

Trump is also trying to coerce local compliance by holding over Chicago’s head the billions of dollars in federal grants that the city receives each year to help pay for law enforcement, mass transit, and roads. During his first term, Trump’s attempt to withhold funding was thwarted by a federal judge, who ruled that such efforts were a form of commandeering and, as such, violated the Constitution. That legal battle was never entirely resolved, though: An appeal reached the Supreme Court but was eventually dropped by the Justice Department after President Joe Biden took office. That leaves some legal wiggle room for Trump’s administration. There are other ways Trump could punish Chicago, too: Already, the Small Business Administration closed its Chicago office, citing the city’s noncompliance with federal immigration policy.

And of course, the laws themselves could change. A bill called the No Bailout for Sanctuary Cities Act stalled in Congress last year but is again coming up for a vote. If passed, that law would make cities such as Chicago ineligible for federal grants that are used to benefit residents without legal status.

In Chicago, several community organizations have tried to parry such attacks, filing their own lawsuit against the federal government, arguing that Trump’s targeting of the city and its sanctuary law is itself in violation of the First Amendment and other legal protections. (They dropped their suit in late February.) Sheila Bedi, who represented the groups through Northwestern University’s Community Justice and Civil Rights Clinic, says the Trump administration is making a spectacle of Chicago and other blue cities not because of legitimate concerns about crime but in order to silence dissent.

All this is happening at a moment when Chicago’s appetite for resistance appears less robust than it was during Trump’s first term. Texas’s busing here of some 50,000 migrants from Venezuela and other Latin American countries, almost all of them in need of essential services, created tension between Black and immigrant communities over the best use of city resources. As Trump invariably applies more pressure, those cracks could continue to grow. Or the increased attacks could backfire, galvanizing a resistance. Chicagoans, after all, don’t much like being pushed around.