It was bitterly cold on January 26, 1966, the day Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta, moved into a $90-a-month railroad flat on the top floor of a rundown building on the corner of Hamlin Avenue and 16th Street. The North Lawndale tenement, which stood two blocks from a pool hall that served as headquarters for the Vice Lords street gang, had no lock on its front door and a packed-dirt floor in the foyer.

Just 11 days after his 37th birthday—and coming off the history-making triumphs in Birmingham and Selma that laid the groundwork for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and, a year later, the Voting Rights Act—King had come to Chicago to make the city the next proving ground for his nonviolent revolution. In the South, King and his followers had taken on Jim Crow segregation at lunch counters, on buses, and in voting booths; in the North, his crusade, called the Chicago Freedom Movement, would confront a less overt but equally insidious injustice: namely, the discriminatory and duplicitous real estate practices, such as steering, redlining, and panic peddling, that kept blacks boxed inside big-city ghettos. “If we can break the system in Chicago, it can be broken any place in the country,” King declared at a summit of community organizations in 1965.

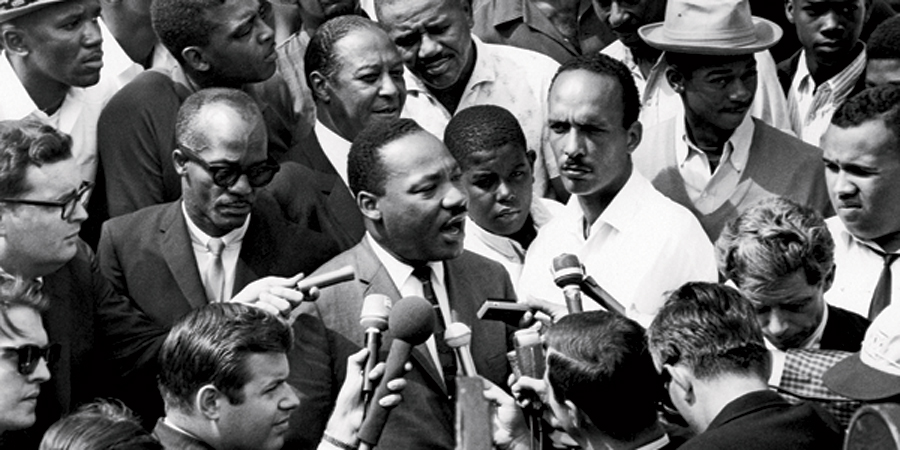

During the sweltering summer of 1966, the campaign—King’s first major one outside the Deep South—culminated with the kinds of demonstrations and marches into all-white neighborhoods he’d employed earlier. They triggered open violence—most famously during a march in Marquette Park, where King was attacked by an angry mob. The marches—which will be commemorated with the unveiling of a permanent art installation in the park on August 5—exposed to the entire world Chicago’s simmering cauldron of racial tensions, which Mayor Richard J. Daley had, until then, managed to keep from boiling over. “I think the people from Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate,” King said afterward.

But the movement that began with great fanfare and climaxed with dramatic marches ended with little more than a shaky truce between King’s forces and Daley’s coalition of white civic and business leaders. Critics derided the deal, saying it wasn’t worth the paper it was written on. Nevertheless, King claimed victory, left town, and turned his attention to the Vietnam War and, after that, to organizing what he called the Poor People’s Campaign. Within a year and a half of the conclusion of the Chicago Freedom Movement, he was assassinated.

Much has changed in 50 years. Racial boundaries have fallen, or at least shifted dramatically. In 1966, Chicago Lawn, the Far Southwest Side neighborhood that includes Marquette Park, was 99.9 percent white—mostly Germans, Poles, Irish, and Lithuanians. Today, it is split almost evenly between blacks and Hispanics, with relatively few whites and a small but growing number of families from the Middle East. Institutionalized discriminatory practices like redlining are a thing of the past, and blacks have come to hold positions of power throughout the city and country, including the highest office in the land.

Much has stayed the same, too. Having earned the dubious distinction of being America’s most segregated big city more than five decades ago, Chicago remains deeply split along racial lines. Today, most blacks live, as they did in the 1960s, on the South and West Sides, where they are the majority, often overwhelmingly so; a recent study by the University of Illinois at Chicago found that nearly three-quarters of the city’s black and white residents would have to move to a different census tract to achieve a true racial balance. What’s more, many of the problems that plagued the city’s black neighborhoods in 1966 haven’t gone away and have arguably gotten worse: gun violence, lack of jobs and economic mobility, and struggling schools. Then there’s the issue of police abuse, dragged into the light by a dashcam video.

Many Chicagoans today see Laquan McDonald—fatally shot by an officer last year, some 30 blocks from the house where King lived—as the supreme symbol of that abuse. But in many ways he embodied, in both life and death, the whole range of problems that King had hoped to overcome. Born to a 15-year-old mother, McDonald bounced around foster homes before living with his great-grandmother in subsidized housing on the Far West Side; he attended some of the worst public schools in the city, and by the time he was 12, he had plunged into the world of drugs and gangs. As Marvin Hunter, a minister and McDonald’s great-uncle, put it at a press conference last December: “Laquan McDonald represents thousands of Laquan McDonalds—same black skin, same poverty, same social and economic injustice that is put upon them, but with different names and ages. … I feel like it’s America’s and Chicago’s chickens coming home to roost.”

McDonald’s death ripped open wounds that had never really healed in the 50 years since King’s historic Chicago campaign. It has left many, especially those old enough to remember King’s visit, wondering how far we’ve actually come since 1966 and has prompted people to again pose the question—to borrow from the title of King’s last book—where do we go from here?

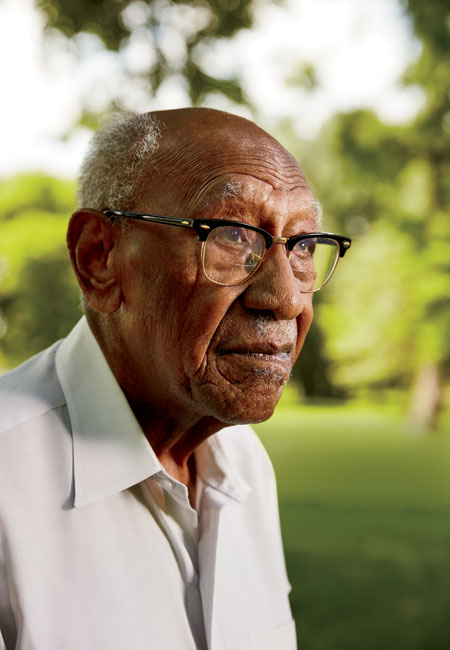

I pick up Timuel Black at his South Side apartment, and we head over to Pearl’s Place, a white-tablecloth soul food joint inside the Amber Inn in Bronzeville. Wearing a red plaid flannel shirt, brown corduroys, and an “Obama ’08” ski cap atop a halo of white hair, he is greeted like a celebrity. “How ya doin’, Professor?” the owner says, putting an arm on his shoulder. Like a politician, Black shakes hands all the way to our table in the back of the restaurant.

An acclaimed civil rights activist, educator, and historian, Black is a walking encyclopedia. He’s lived in Chicago for practically all of his 97 years. “The story goes,” he says, “when I was 8 months old in Birmingham, Alabama, I looked around and saw what was going on and said to my mama, ‘Shit, I’m leaving here.’ ” The real story: Black’s parents moved the family to Chicago in 1919, fleeing the racial terror of the postbellum South. “My father was one of those people who didn’t accept segregation,” Black says. “Those were the people who got lynched.”

Over lunch, Black gives me a history lesson. You can’t understand the significance of the Chicago Freedom Movement, he tells me, unless you understand the Great Migration, the mass movement of humanity that brought millions of Southern blacks to Chicago and other Northern cities over the course of much of the 20th century in search of jobs and freedom from Jim Crow. This influx reshaped the city demographically and socially as much as its skyscrapers altered it physically.

At the turn of the century, Black explains, only 30,000 or so of Chicago’s 1.7 million residents were black. By the time King arrived in the city—just as the Great Migration was drawing to a close—fully one-third of Chicago’s population was black and its racial map had profoundly changed. Many whites met these changes with hostility. In 1919—the year Black’s family moved here—a multiday race riot left 38 people dead and more than a thousand homeless. Chicago was hardly the racial haven Southern blacks had been seeking. As the columnist Mike Royko put it in his book Boss: “The only genuine difference between a southern white and a Chicago white was in their accent.”

Ghettos became the most visible legacy of the Great Migration. In the 1920s, white real estate agents introduced restrictive covenants, which made it illegal for homeowners in all-white neighborhoods to sell or rent to blacks. Black families began to cluster in a part of the Near South Side that came to be called the Black Belt, later nicknamed Bronzeville. “People like myself,” says Black, “we lived in confined quarters, in a little city within a city.” Though by state law blacks had equal access to restaurants, hotels, soda fountains, and other public places, as late as the 1950s, says Black, “Negroes weren’t welcome downtown.” So they created their own version on the South Side: vibrant commercial strips, including the Stroll along 35th Street and Blues Alley on 43rd, bustling with barbershops, beauty parlors, nightclubs, juke joints, and even the city’s first black-owned bank.

But by midcentury, Black explains, exclusionary real estate practices had turned Bronzeville into a crowded ghetto. “The population density outside the Black Belt was something like 27,000 people per square mile,” he says. “In this neighborhood, it was 84,000.” Grand old graystones were cut up into smaller apartments known as kitchenettes, which in turn were subdivided even further as the neighborhood’s population grew. Even after the U.S. Supreme Court declared restrictive covenants unenforceable, discriminatory schemes to keep blacks out of white areas persisted. The most notorious was redlining, the refusal of banks and insurance firms to issue or insure mortgage loans in predominantly black neighborhoods, which would often get delineated on city maps with a red line.

As the black population grew, the Black Belt eventually loosened, and blacks started pushing into white neighborhoods (often paying double the market value for white-owned homes). “Realtors would sell a piece of property to a Negro,” Black says, “and then they tell the white people, ‘The Negroes are coming!’ ” These blockbusters, as such real estate agents were called, fanned white panic, warning residents that the value of their homes would plummet. Many whites sold quickly and left, most often for the suburbs.

By the mid-1960s, on the eve of King’s Chicago campaign, the Harlem of Chicago, as Bronzeville was often called, was well on its way to becoming blighted. Many of its graystone blocks had been replaced by the two-mile stretch of bleak concrete towers known as the Robert Taylor Homes or by the eight massive apartment blocks of Stateway Gardens. These public housing complexes would become, arguably, the country’s most notorious.

At the end of my visit with Black, he poses a question: “Why does race matter?”

I start fumbling for a response, but he stops me. “It’s not too complicated,” he says. “It’s economic, as I see it.”

Black goes on to tell me that Chicago’s racial problems, and America’s, have nothing to do with racism and everything to do with economic exploitation and pure self-interest—a way to take advantage of overcrowding, to secure economic advantages, to preserve power.

Whatever the underpinnings—racial, economic, or both—this was the status quo King was seeking to upend.

Five months before Martin Luther King moved into the Hamlin Avenue flat, his attention—like that of many Americans—was focused on Los Angeles, not Chicago. The 1965 Watts riots—which occurred within days of the signing of the Voting Rights Act, one of the most significant victories of King’s movement—jolted him awake to the struggles faced by urban blacks outside the South. As King told a New York newspaper, “The non-violent movement of the South has meant little to them, since we have been fighting for rights that theoretically are already theirs.”

King’s decision to come to Chicago owed in large part to the efforts of two men: Albert Raby, a mild-mannered but headstrong teacher-turned-activist who for several years had led massive protests over the de facto segregation of the city’s public school system, and James Bevel, an outspoken young minister who had been an indispensable strategist in some of King’s most pivotal campaigns. Bevel had recently moved to Chicago with his wife, Diane Nash, a native South Sider, and started working at the West Side Christian Parish, an outreach ministry across from Union Park.

Raby and Bevel convinced King that Chicago would be the ideal beachhead: It was a huge city with a substantial black population, and unlike New York and Philadelphia, where influential black leaders let it be known to King privately that they didn’t need or want him, Chicago had a coalition—led by Raby and Bevel—ready to welcome him with open arms. And then there was Chicago’s mayor. Richard J. Daley controlled virtually every lever of power in the city. Persuade Daley of the rightness of change, Bevel and others argued, and the whole city would change along with him. Change Chicago, and the rest of the country would follow.

“We’ve got to go for broke,” Bevel told King. After the Watts riots, King didn’t need much convincing.

The task of finding King a place to live fell to his assistant, Bernard Lee. King had expressed a desire to live on the West Side. “You can’t really get close to the poor without living and being here with them,” King told reporters. “A West Side apartment will symbolize the slum-lordism that I hope to smash.”

Lee and a young secretary named Diana Smith, who had grown up in North Lawndale, posed as a house-hunting couple and, after a week of looking at apartments in and around that neighborhood, settled on the flat at 1550 South Hamlin Avenue. Lee signed the lease before the landlord realized who the real occupant would be. Once he did, he promptly sent over a crew of plasterers, painters, and electricians to fix up the apartment.

“For a long time there was a joke that all Martin Luther King had to do was to move from one building to another on the West Side, and the whole place could get cleaned up in a hurry,” recalls Mary Lou Finley, who coedited a recent book on the Chicago Freedom Movement. Finley, who is white, was just out of Stanford in 1965 and was given the job of picking out furniture from a church-run thrift shop for the Kings’ two-bedroom apartment. She remembers clearly the tiny kitchen with the refrigerator that didn’t keep food cold and the dilapidated gas stove that didn’t keep it hot.

Coretta Scott King recalled the flat in her memoir, My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr.: “Our apartment was on the third floor of a dingy building, which had no lights in the hall, only one dim bulb at the head of the stairs. … As we walked in … the smell of urine was overpowering. We were told that this was because the door was always open, and the drunks came in off the street to use the hallway as a toilet.”

The Kings’ apartment was right off a violent stretch of 16th Street, in a part of North Lawndale nicknamed the Holy City—holy because it was where the Vice Lords, one of Chicago’s largest and fiercest gangs, had gotten its start. “In all of my time in the movement all across the South, the only time I was scared was in that neighborhood, going to my apartment at night,” recalls Andrew Young, the former congressman, U.N. ambassador, and mayor of Atlanta, who as a young activist accompanied King to Chicago to help launch the campaign. “I said, ‘I don’t mind giving my life in the civil rights movement, but damn if I want to have a knife stuck in me for 20 dollars in a dark hallway.’ ”

Most of the businesses in this part of the West Side—grocery and liquor stores, payday loan shops, and the like—were owned by whites, many of whom had lived in the neighborhood before blacks moved in. (In 1950, North Lawndale was 87 percent white. A decade later, it was more than 90 percent black.) Customers in these neighborhoods almost always paid more for less. Says Finley: “I remember going to a grocery store and finding Grade B eggs. Never in my life had I seen Grade B eggs anywhere! And they cost the same as Grade A or AA eggs in other grocery stores.” One day, she recalls, a colleague followed a delivery truck that picked up boxes of expired potato chips from a suburban supermarket and brought them to grocery stores on the West Side. “The ghetto was a dumping ground,” says Finley.

After getting settled in the Hamlin Avenue flat, King established a routine of strolling around the neighborhood. On his walks, he saw up close the sense of hopelessness, despair, and anger—what he referred to as an “emotional pressure cooker”—to which the Watts riots had so violently borne testament.

By 1966, there had been a fair-housing ordinance on the books in Chicago for several years, but on the ground, as King could plainly see, very little had changed. Because prohibitive prices and the threat of violence still kept blacks from buying or renting homes wherever they wanted, they remained relegated to the ghetto, mired in all of the inequalities found there.

Where’s the blue?” Dorothy Tillman asks the church custodian incredulously. “It’s beige. When I was here last year, it was still blue.”

On a rainy afternoon, Tillman, who worked as a youth organizer on King’s staff, is showing me around the basement of the New Greater St. John Community Missionary Baptist Church in East Garfield Park. This used to be the headquarters of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference for the Chicago campaign. Back in 1966, it was called the Warren Avenue Congregational Church, and the basement walls were robin’s-egg blue. “Our whole operation was from here—this was our main office,” says Tillman. “It was called the Blue Room. The Blue Room is where we did all our thinkin’ in. But it’s all different now.”

She strides over to the back wall and bangs on it. “This wasn’t here. All this was open, all through here.” She peeks around the doorway. “When Dr. King would come, we’d meet back there in his office for strategy meetings.”

It’s hard to imagine the Nobel Peace Prize winner working here. His old office is now a musty storage space, coated in dust and cobwebs.

Tillman, now 69 and a well-known former alderman with a fondness for flamboyant hats (on this day, a bright red one with a black bow), was just 17 when she came to Chicago from her native Alabama in the fall of 1965 as part of an advance team to help prepare for the campaign.

Chicago was a shock. “I didn’t like it,” she says. “It was such a strange place. It was the first place I saw a dog mess on the sidewalk. I couldn’t believe it, ’cause I’m a Southerner; dogs don’t come in the house, and they don’t mess on the sidewalk.” Then there was the weather: “The sun didn’t shine for a whole week.” She remembers the first time she laid eyes on the Robert Taylor Homes, while traveling around the neighborhood with James Bevel: “I said, ‘Oooh, what are all those factories doing in the middle of the city?’ And Bevel said, ‘Those aren’t factories—those are houses. People live in there.’ And I said, ‘Whaaaat?’ ”

More unsettling than all that, Tillman says, was how a lot of Chicago’s black ministers—even a few who had marched with him down south—rebuffed King. Far from rolling out the welcome mat, they told him in plain terms—in front of TV cameras, no less—to butt out and go home. “We were rejected by most of the black leadership,” says Tillman. “Dr. King could hardly get into a church to speak. We never experienced that before. And I told Dr. King, I said, ‘If they don’t want us to be here, I don’t want to stay. I want to go back home.’ ”

Back then, she says, Chicago’s black politicians, as well as nearly all of the city’s black ministers, were in the stranglehold of Mayor Daley’s Democratic machine. “Dr. King said that Daley’s plantation was worse than the plantation in Mississippi,” says Tillman. “He’d say, ‘Those Negroes was in deep.’ ”

Ministers who backed the administration’s policies got rewarded with patronage and political favors—$1 city lots for church expansions, say, or federal money for social service programs. Those who didn’t play ball got punished with visits from city building or health inspectors, or Sunday parking tickets, or permit and zoning denials. Tillman likes to tell the story of the South Side pastor Clay Evans. In 1964, Evans defied Daley and let King preach at his church, which happened to be under renovation. The next day, the lending institutions that were bankrolling the construction withdrew financing, and the crews stopped work. Evans continued to support King throughout the Chicago Freedom Movement; his church addition stood unfinished for eight years.

Now Tillman leads me into the New Greater St. John church’s sanctuary, which, unlike the basement, is still blue. Pointing out where King used to sit, she says, “You can probably find some pictures of us singing.” She stretches her arms toward the heavens. “We’d be singing, boy!” She breaks into song and starts clapping. “Oooh, ohh, freeee-dom! Oh yeah! We’d be having a good time!”

For all of the hoopla surrounding King’s arrival, the campaign started slowly. King spent his first weeks touring the city and meeting with local activists, city officials, and ghetto residents. One frigid day in late February, King and some of his staff, dressed in work clothes and with reporters and photographers in tow, helped clean up a rat-infested tenement at 1321 South Homan Avenue. “There was no heat, and there were babies wrapped in newspaper ’cause there were no blankets,” recalls Andrew Young. “We brought coal for the building and fired the furnace.”

A week later, King made his first bold play of the campaign, leading a procession of 200 people back to that same building and announcing that the Chicago Freedom Movement was assuming “trusteeship” of the property on behalf of the tenants. The tenants’ monthly rents would be paid to his organization, not the landlord, and used for repairs. The dramatic move, meant to shed light on the problem of absentee owners of derelict buildings, garnered much attention—though the tenement’s owner turned out to be a frail 81-year-old who told reporters, “I think King is right.” (He ultimately decided to fight the takeover in court and won.)

In the months that followed, King’s forces mounted an aggressive “End Slums” initiative, sponsoring tenants’ unions, organizing rent strikes, conducting workshops on nonviolence with youth gangs, and calling for the boycotting of businesses that discriminated against blacks. Overall, though, these early actions struggled to gain traction and sway public opinion in a significant way.

Mayor Daley consistently outmaneuvered King’s forces, co-opting them at every opportunity. “All of us are for the elimination of slums,” Daley said, seeking to present himself, and not King, as the champion of the city’s poor black residents. He touted rodent eradication projects, education programs, new public housing. He sicced his army of building inspectors on slumlords and made sure the code violations were printed in the newspapers. (The owner of the tenement on Homan Avenue that King’s staff took over was slapped with 23.)

Daley didn’t want to play the role of George Wallace in King’s Chicago drama. He wasn’t going to let King or his followers become martyrs, not in his town. As Tillman recalls, “Daley said, ‘Y’all got popular because you went to jail—I’m not gonna put you in my jails.’ ” Tillman tells me about the day when she and some other activists were arrested on the West Side for painting protest messages on the sidewalk. After Young called Daley and, according to Tillman, said, “I understand you got some of my people in jail,” the mayor made an angry call to the police commander: “Get them folks out of my jail right now. Don’t you ever pick them up again.”

By summer, many on King’s staff and those they worked with in Chicago were grousing about the campaign’s slow pace and lack of direction. Money was running short. Infighting was hampering progress, with some activists calling for increased militancy, a route favored by America’s growing Black Power movement. “The trouble here,” Young told reporters at the time, “is that there has been no confrontation. … We haven’t found the Achilles heel of the Daley machine yet.”

The same day as our visit to the church in East Garfield Park, Dorothy Tillman takes me to the New Friendship Baptist Church in Englewood. It was here on July 28, 1966, that the Chicago Freedom Movement reached a turning point. For weeks, campaign organizers had been sending blacks posing as homebuyers and renters into real estate offices in white working-class neighborhoods. Almost invariably, they’d be told nothing was available—even though the whites sent in soon afterward would be shown a long list of properties. Campaign leaders then staged protests and prayer vigils near these real estate offices. Standing before hundreds of supporters gathered at New Friendship on that sweltering July day, King declared that more “creative tension” was needed and that they were going to march into the all-white neighborhoods surrounding the black ghetto, starting with the Irish and Lithuanian stronghold of Gage Park.

Two days later, Young, Raby, and other top lieutenants led roughly 450 marchers from New Friendship to H.F. Halverson Realty, at 63rd Street and Kedzie Avenue, in the heart of Gage Park. (King had a speaking engagement and was not present.) They were met by a heckling white crowd, and they left, under police protection, in paddy wagons.

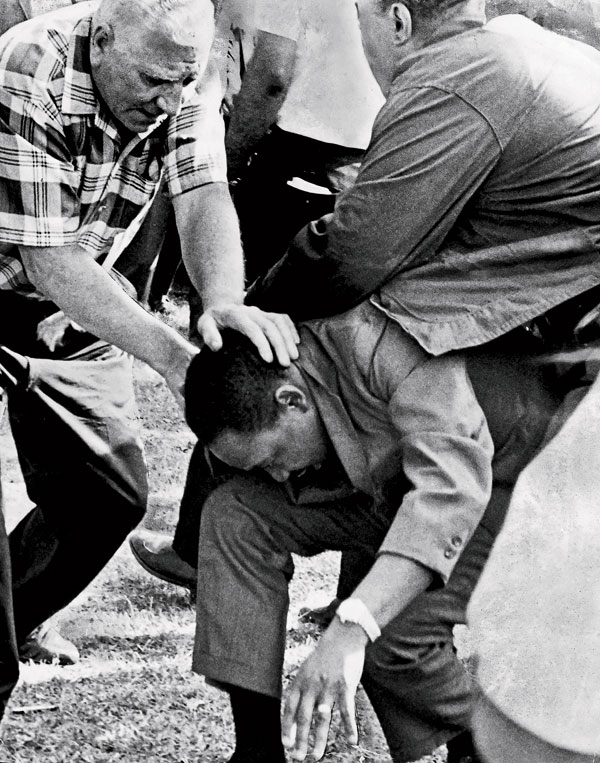

Sensing they had erred and should’ve stood their ground, the protesters, who now numbered 500, marched again the next day, this time into Marquette Park. Hundreds of whites were waiting and hurled rocks and bottles at them, set fire to the cars that had brought them to the park, or pushed them into the lagoon. Police officers did little to stop the melee. The marchers retreated to New Friendship—where, Tillman remembers, the campaign had stationed medical staff. They quickly began tending to the injured, some 50 in all.

On the afternoon of August 5, 800 marchers returned to Marquette Park, this time in the company of King. The veteran political consultant Don Rose, who was King’s press secretary during his time in Chicago, remembers the terror he felt crossing Ashland Avenue, which marked Englewood’s color line at the time. It went from complete peace and quiet on one side, he says, to thousands of screaming, jeering, and taunting whites on the other. A mob had gathered on a grassy knoll nearby, he says, waving Confederate flags and yelling “Niggers go home!” and “We want Martin Luther Coon.” An extralarge police force—under Daley’s orders—escorted King and the marchers through the park as rocks, bottles, eggs, and firecrackers rained down on them.

Andrew Young describes a moment from that day that stands out in his memory: “I remember this young woman running up in front of the march and getting in Dr. King’s face and calling him all sorts of vile names, just spewing out venom. He said, ‘You know, you’re much too beautiful to be so mean.’ And it stunned her. She turned around and walked away. And when we came back through that neighborhood on the way to the cars, she came back out of the crowd again and said, ‘Dr. King, I’m sorry, I don’t want to be mean. Please forgive me.’ ”

At one point King was struck in the head by a fist-size rock. Shaken, he sank to one knee and remained dazed for several moments as the crowd chanted, “Kill him, kill him.” Then he rose and marched on. Timuel Black was just steps behind King when the rock struck him. As Black recounts, “I said to myself, ‘If one of them bricks hit me, the nonviolence movement is over.’ ”

King told reporters: “Oh, I’ve been hit so many times I’m immune to it.” Later, he added, “I have to do this—to expose myself—to bring this hate into the open.”

When the marchers finally got to the real estate office in Gage Park, they knelt in prayer.

The TV cameras had been rolling the whole time, showing King and his followers resolute in the face of vicious violence. This was the martyrdom moment Daley had wanted to avoid at all costs. King and his marchers had finally found the mayor’s Achilles’ heel.

On August 26, at the Palmer House Hotel—after several days of negotiations—King and Daley reached a deal, known simply as the Summit Agreement. King agreed to stop marching. City Hall and the Chicago Real Estate Board pledged to try to do more to make housing open and fair. The board also promised to stop opposing state housing legislation. And the assembled banking leaders said they would lend money to qualified homebuyers, regardless of race.

The pact was neither codified nor legally enforceable, but King was exultant nonetheless. “They said nonviolence couldn’t work in the North,” he told supporters after the agreement was signed. “They said you can’t fight City Hall; you better go back down South. But if you look at what happened here, it tells you nonviolence can work. … Never before has such a far-reaching move been made.”

To other black leaders, though, the Summit Agreement was equivalent to surrender. Some questioned the strength of King’s leadership. Others questioned the principle of nonviolence. “The poor Negro has been sold out by this agreement,” the activist Chester Robinson bluntly put it at the time. Even some in King’s inner circle, including Bevel and Young, weren’t sure what to make of the deal. When reporters asked Bevel for his reaction, he replied, “I don’t know. I have to think about it.”

King himself eventually hinted at a more sober assessment. “In all frankness,” he said a few months after the agreement was signed, “we found the job greater than even we imagined.”

Jesse Jackson’s office at the Rainbow PUSH Coalition headquarters, in a neoclassical former synagogue in Kenwood on the South Side, is a shrine to the 74-year-old activist’s public life: photographs, certificates, and plaques on the walls, dozens of items of memorabilia in a glass case.

Jackson was a young pastor, fresh out of the seminary, in 1966 but had already become one of King’s top lieutenants, heading up the Chicago chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Operation Breadbasket, PUSH’s precursor. Now, seated behind his desk, he reflects on the culmination of King’s campaign. “You put Dr. King, a rabbit, right in the briar patch,” he says. “Mass marches, mass reactions. That’s what began to push the movement to the limits. That made it Birmingham.”

The question of whether the Chicago Freedom Movement was a success or a failure irks Jackson. Calling it a sellout is simply wrong, he says, as is believing that a struggle dating back to the time of slavery could be solved by one man in a matter of months. “You know, [critics say], ‘King came, and nothing changed.’ Well, a lot changed.” He starts reeling off a list of the campaign’s accomplishments: It helped erase neighborhood color lines; it led to greater equity in housing, including the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968; it opened up economic and political opportunities for blacks; it galvanized black youths. “Chicago set the pace for the rest of the country,” he says.

We go into the hallway, the walls of which are lined with more photos, most of them showing Jackson with civil rights figures, politicians, world leaders, and entertainers. Jackson pauses in front of a black-and-white picture of him in the pulpit of the nearby St. James United Methodist Church in 1966 or 1967. “Dr. King, he was hoarse that night and couldn’t speak,” he explains. “He asked me to speak for him.”

We inch our way down the hall. More photos: of protests and picket lines, of groundbreakings and ribbon cuttings for black-owned businesses, of rallies and parties. Finally, Jackson points to a grainy picture of a smiling, waving King with Coretta and several staffers, all of them looking out the open top-floor windows of a brick building. It’s the Hamlin Avenue tenement. The photo, Jackson says, was taken on the day King moved in.

Jackson seems to be showing me all this to illustrate a point: Hanging on these walls is photographic proof of a half century of black progress. “A lot of stuff came out of the ’66 Freedom Movement,” he says. “My own platform came out of here.”

That’s true. King had handpicked Jackson to head up Operation Breadbasket, and it became a crucial component of the Chicago campaign, using picket lines and boycotts to force businesses in black neighborhoods to hire black workers, use black-owned banks, and stock black products and brands. Operation Breadbasket is thought to have brought up to 3,000 jobs to Chicago blacks within two years.

Jackson gazes at the photos for another moment or two. “We’ve been meeting every Saturday morning for 50 years,” he says. “We never stopped.”

The Hamlin Avenue tenement where King lived is gone now, demolished in 1979. It had been damaged in the rioting that followed King’s assassination on April 4, 1968. In its place stands the Dr. King Legacy Apartments: a modern low-rise building with a handsome brick façade. Built in 2011 by the Lawndale Christian Development Corporation, a nonprofit that develops affordable housing, the complex contains 45 mostly subsidized rental units and, on the ground floor, a shoebox-size museum that celebrates King’s Chicago campaign.

The property is an oasis amid eyesores of the type King might have passed on his walks through the neighborhood 50 years ago: trash-filled vacant lots, boarded-up graystones, abandoned businesses, and, in an alley just across the street from where King lived, a notorious drug market. Its commercial life all but extinguished after the riots and its job base decimated by deindustrialization, Lawndale is today the second-most dangerous neighborhood in the city. On the first day the Dr. King Legacy Apartments began accepting applications, more than 400 families applied.

If, as the subtitle of King’s final book suggests, the answer to the question of where we go from here is either chaos or community, then Lawndale seems to be moving inexorably toward chaos, as do many of Chicago’s black neighborhoods.

Solutions are hard to come by. Many studies point to persistent segregation as a root cause of the social ills plaguing poor neighborhoods, which are caught in a vicious cycle of disinvestment and isolation, but many black Chicagoans have all but given up on the notion of integrating the city’s racial enclaves. Some, including Dorothy Tillman, believe that nothing short of a multibillion-dollar initiative—akin to the Marshall Plan in postwar Europe—will change the conditions in impoverished neighborhoods. Meanwhile, the discouraging headlines about crime, joblessness, and police abuse keep coming, as do fresh victims of that abuse and deprivation—new Laquan McDonalds.

As for Timuel Black, he remains optimistic, though he’s been around long enough to know that the kind of change Chicago needs won’t come about quickly. “It’s a step-by-step operation,” he tells me. “The main thing is, change is gonna come. It’s gonna take some time. Maybe you’ll be as old as me before it happens. But it’s gonna happen.”

For his part, Jesse Jackson believes that King always intended his Chicago campaign to be part of a “long-distance strategy”—that it was never meant to be a “six-month movement, like Selma or Birmingham.”

Fifty years on, there’s still a lot of distance left to cover.