On a crisp March day in Hyde Park, a group of people, most of whom have never met face to face, are having a reunion. Twenty undergraduate and graduate researchers, administrators, and professors cram into the former servants’ quarters of a converted mansion. Some find seats around a long table, while others spill into the hallway or perch beneath a whiteboard on which is scrawled “Winter 2022. Stated Motives Analysis.”

Mateo Garcia, a student research supervisor, sits at a computer. His screen bears the words “Project Insurrectionists.”

“Today’s the first time I’m seeing a lot of these people in person,” Garcia says. He nods toward a lanky student he’d previously encountered only on video. “He’s much taller than I thought.”

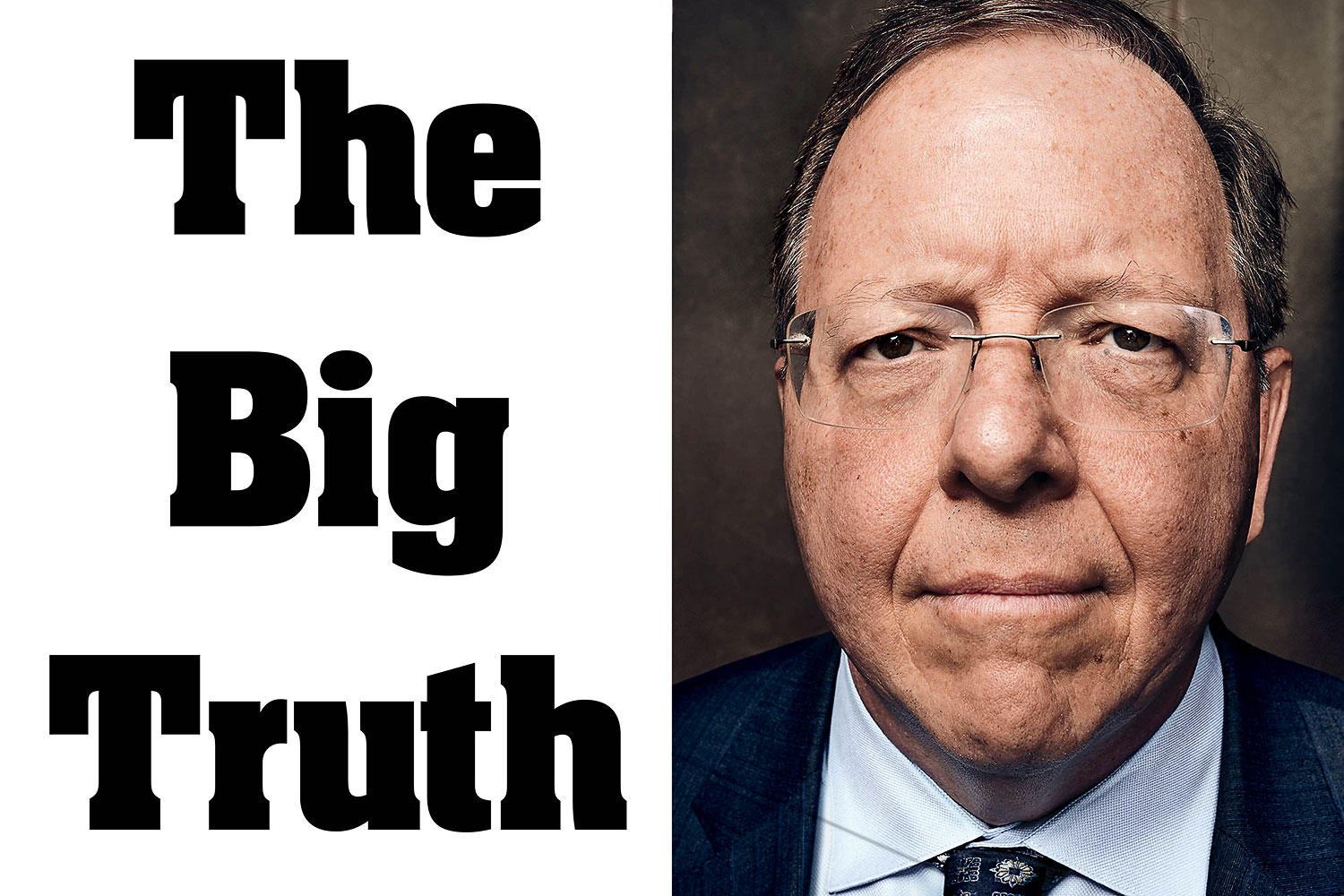

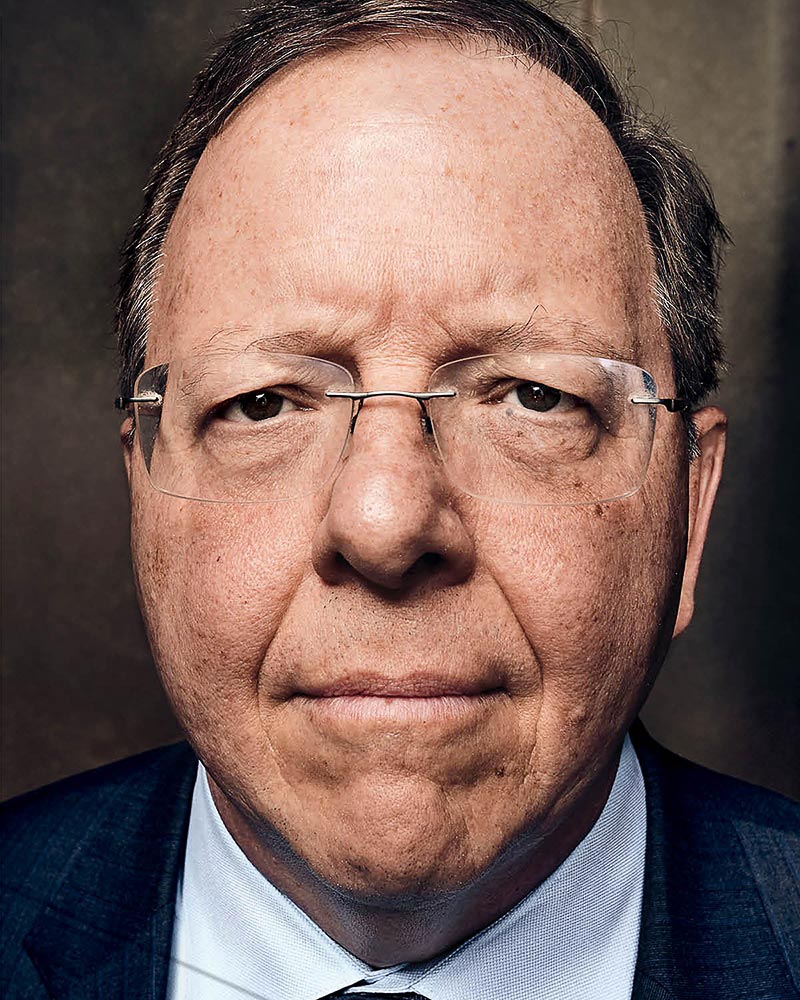

Seated at the end of the table is the crew’s patriarch, Robert Pape, with his frameless glasses, navy blazer, blue shirt and tie, and easy smile. He has a matter-of-fact way of presenting complicated information, which is in keeping with his mission. As the director of the Chicago Project on Security and Threats, the 62-year-old University of Chicago political science professor is trying to understand and to explain American political violence, largely through the prism of the January 6, 2021, insurrection.

Gathered before him is his investigative team, which combs through every detail of court filings, press clips, social media posts, and virtual detritus seeking clues about people who would resort to violence to overturn an election. What these researchers have discovered so far has engaged and disturbed government officials and others concerned that the storming of the Capitol was not a culminating event but an opening volley. While the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6 Attack on the United States Capitol focused on the top-down planning behind the mob action, Pape and his team have homed in on the foot soldiers being driven to attack. In addition to illuminating who the insurrectionists are and what motivated them that day, they’ve also established that millions of other Americans sympathize with their cause.

Where this work is taking place — the University of Chicago — is both irrelevant and critical. Two years before this gathering, the COVID-19 pandemic rendered CPOST a virtual operation. To Pape, this was the proverbial blessing in disguise. No more researchers taking turns on the computers in CPOST’s small suite of offices atop this mansion. No more navigation of complicated schedules to get everyone in the same place at the same time. Most of this research was being conducted online anyway. “We are 60 percent more productive than we ever were,” Pape boasts. At one point, two of CPOST’s full-time staffers lived in Portugal. One key member is based in New Jersey, another in New Hampshire. “We have a small, smart army of researchers who work for us remotely,” says Pape, who operates out of a converted back bedroom in his south suburban home.

At the same time, he doubts this project could have originated anywhere other than Chicago — the university or the city. The school gave Pape a break from teaching this past year so he could focus on research, and he has been productive. He has authored or coauthored articles in the Atlantic and the Washington Post, among other outlets, and CPOST has issued numerous reports since the insurrection. Although Pape has consulted with multiple presidential administrations, he has been particularly in demand of late. He spent two days briefing the Biden administration at the White House and has met with the CIA, FBI, and Pentagon. The House January 6 committee asked Pape for extensive written testimony, and in June he testified at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing titled “Examining the ‘Metastasizing’ Domestic Terrorism Threat After the Buffalo Attack.”

“He is now seen in [Washington, D.C.] — specifically in the intelligence agencies and National Security Council — as one of the real experts in the area of terrorism and cybersecurity,” says Chuck Hagel, who served as secretary of defense under President Barack Obama after two terms as a Republican senator from Nebraska. “Because of what’s been happening in the world the past few years, he’s become more and more important and more and more recognized.”

What Pape and his colleagues have found is that those who attacked the Capitol were not, as had been widely assumed, an assemblage of rural Donald Trump voters linked to fringe right-wing groups. The movement appears to be far more mainstream than that, with a surprisingly broad base of support for political violence. CPOST continues to examine the insurrectionists — their demographics, attitudes, and social connections — to present a more comprehensive picture than has been seen anywhere. This is academic work meant to stand above the partisan fray, though it’s also intended to have a real-world impact. Pape’s stated purpose is not to craft policy but to provide vital information to those who do, as was the case with CPOST’s previous work on suicide terrorism and domestic ISIS recruitment.

Yet the current state of politics puts Pape and his colleagues in a tricky situation. Can a fact-based approach prevail when many of the subjects — people who supported overturning a presidential election through violent means — subscribe to a conspiracy theory called the Big Lie, the claim that the 2020 election was stolen? Or when other Trump allies, including some of the very politicians who were forced to evacuate the Capitol, have downplayed, even defended, the insurrection? How can researchers avoid the trappings of politics when facts themselves are deemed partisan?

CPOST already had its hands full on the morning of January 6, 2021. The researchers had reassembled two days earlier, the Monday after winter break, and were continuing their work on a project launched in the summer of 2020 to study the nature of protests and violence in 50 cities following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. But more pressing was a review, due at the end of that month, in which Pape and his team were examining whether the pandemic had slowed or accelerated the pace of terrorism worldwide in 2020.

When the team took a break around lunchtime, Pape visited the New York Times website and saw what was unfolding at the Capitol. He’d been worried about violence erupting during a contested election and even mentioned January 6 specifically on WTTW’s Chicago Tonight back in early October, a month before the election. “So I knew it was going to be a big deal,” Pape says. He turned on the television and became glued to CNN and Fox News “like everybody else.”

As some 2,000 Trump supporters breached the Capitol, Pape maintained his analytical disposition, just as he had while watching the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. “It wasn’t about feeling emotional,” he says. “It was about knowing I needed to understand what was happening. That was very important to do. There was a major threat to our government that was occurring right in front of us.” The attack left five people dead and around 140 police officers among the injured, with four of them taking their own lives in its aftermath.

By the next day, the arrests had begun. Arrests meant data. Pape called Keven Ruby, CPOST’s research director, and suggested the group “revector” its teams immediately to study the insurrection. Ruby was hesitant. “Was this really going to be worth reprioritizing?” Ruby recalls wondering. “Were we going to get the kind of data that is going to be meaningful? Are they actually going to arrest any meaningful number of people? Will this answer big enough questions? But Bob was insistent, and he’s the boss, and we shifted priorities, and it’s a good thing we did.”

By the beginning of the following week, CPOST had committed to a challenging new mission. Many months later, the work has yet to let up. “The key thing is he is enormously driven,” Ruby says of Pape. “He is very driven to getting the analysis done and pushing it further.” Ruby, who is based in New Hampshire, will put his phone away on Saturday and Sunday rather than field Pape’s constant queries. “You get emails asking for something, and it’s often because he’s thinking of whatever issue he’s working on over the weekend. If he has any free time, I would be very surprised.”

It’s April, and Pape is leading an informal tour through his base of operations: the midcentury modern three-bedroom ranch house where he lives with his partner, Carol. Pape has organized the space to optimize his time on and off the clock. Turn right from the entrance and you’re in what he calls the outer office, featuring a desk, a leather chair and ottoman, bookshelves, and a display of miniature shoes rendered in precise detail. It was his mother’s collection, and Pape says she never mentioned it before her death in 2017.

As some 2,000 Trump supporters breached the Capitol, Pape maintained his analytical disposition. “I needed to understand what was happening,” he says. “There was a major threat to our government that was occurring right in front of us.”

In this “calmer thinking area,” as Pape describes it, he reads and relaxes. It’s not where he takes care of business. Walk past a bathroom and you find the real office: a corner room that doubles as a TV studio. “I don’t come in here unless I’m working,” Pape says.

The ready-for-prime-time vibe hits you as you step through a panel of dark blue curtains to face a floor-based lighting rig with an inverted triangular cone directed at the ceiling. On the adjacent table sits a large curved monitor with a camera on top and Bose speakers on either side, and a Samson radio-style microphone aimed at the desk chair where Pape sits.

To the chair’s right is a heavy, glass-topped dark wood desk bearing stacks of papers and a black globe. On the floor beneath a window is a puffy bed for Pape’s pug, Darla. She is elsewhere at the moment but is often present while he’s on camera — and has yet to create any viral moments. “She’s good,” Pape says. “She knows I’m on.”

It’s in this room that he informs the government and world about threats to democracy. Pape says he received about 50 press inquiries around the first anniversary of the January 6 attack and sat for 30 or so interviews. He still fields multiple media requests every week from around the globe, though he has been turning most of them down because each one kills a morning otherwise devoted to research.

Looking out from Pape’s computer monitor is the frozen face of Roderick Cowan, CPOST’s then–executive director. (He would leave his post later in the spring.) With a background in law enforcement, security, and magazine publishing and having lived in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United Arab Emirates, Cowan was “a tremendous bridge builder” between the center and the United Nations and other international organizations, Pape says. Despite living in Portugal, Cowan helped Pape optimize his office for video communications and presentation.

This morning Pape is watching a video of Cowan conducting an “ethnographic conversation,” a kind of focus group, with U.S. residents of various political stripes. These interviews, in which subjects discuss their attitudes toward political violence, are another layer of information being mined by CPOST. Cowan speaks with three people at a time on video, his European inflections suggesting a neutral point of view, his questions having been fine-tuned by CPOST senior research associate Kyle Larson. By this day 41 such groups have been interviewed.

“It is a way to listen to America on these really important issues related to political violence,” says Pape, who might spend an entire day taking notes on just one of these videos. “I’m trying to understand, and that’s leading to new questions.”

On the screen, Pape opens a spreadsheet in which he records respondents’ views, using a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), in several categories: Force (is it justified to overturn the 2020 election?), Stolen (was the election?), Patriots (were the insurrectionists?), QAnon (does the respondent subscribe to this massive conspiracy theory?), and Replacement (does the subject believe in the “great replacement” theory, the notion that Democrats are enabling immigrants and other people of color to outnumber and seize the rights of U.S. white people?).

Pape scrolls to group 21, where one subject’s scores are Force, 5; Stolen, 4; Patriots, 1; QAnon, 5; and Replacement, 4. Wait, if someone believes the election was stolen and should be resolved by force, why wouldn’t that person consider the insurrectionists patriots? Pape says the Patriots category has been a bit of a wild card because some interviewees believe right-wing media reports that the January 6 attackers were actually antifa members imitating Trump supporters.

Another subject tallies a high score in QAnon but doesn’t support violence or the insurrection. Others indicate support for all five. A few of the Biden supporters interviewed register a line of 1’s.

“This is what journalism doesn’t do: truly matched analysis,” Pape says, noting that traditional reporting typically doesn’t control for income levels, demographics, partisanship, and various beliefs. “This helps us to see what are the pivotal factors, as opposed to an interest factor.”

Pape knows of no one else doing such extensive research into domestic political violence. He says he recently submitted a paper to an academic journal and had to check a box to indicate the subject. “International violence” was an option; “American political violence” was not. “I call them black hole areas — areas that we don’t have depth of understanding in,” Pape says.

He returns his attention to the screen and listens.

Because so much comes down to political identity these days, let’s get Pape’s out of the way.

For most of his life, Robert Pape — who was born in Erie, Pennsylvania, and earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in four years at the University of Pittsburgh before receiving his doctorate in political science at the University of Chicago in 1988 — voted primarily for Republican candidates. He still considers himself “a liberal Republican,” though he acknowledges that term has lost utility in the current political climate. Pape says he voted for Ronald Reagan twice, then George H.W. Bush twice. But Pape cast his ballot for Bill Clinton in 1996 because of the Democratic president’s role in ending the Bosnian War. “That was a really big deal,” Pape says. He swung back to the Republicans to vote for George W. Bush in 2000. Then the world changed.

At the time that al-Qaeda militants crashed planes into the World Trade Center and Pentagon, Pape was already an established expert on terrorism and suicide attacks, two years into teaching at the U. of C. after stints at Dartmouth College and the United States Air Force’s School of Advanced Airpower Studies. He was on cordial terms with members of the Bush administration, but in the aftermath of 9/11, as government officials built a case for military action in Iraq, Pape told them what they didn’t want to hear: They should stay out of Iraq if they wanted to avoid an increase in suicide attacks. “Unlike some others, I wasn’t concerned about my viability in Washington,” Pape says. “I just went with where the facts went.”

Although many assumed that suicide bombers were driven primarily by Islamic fundamentalism and fanaticism, Pape’s studies showed that their strongest motivating factor was a resistance to foreign incursions into their territory. Events played out as he had anticipated. In 2001, 70 suicide attacks, including 9/11, took place around the world, he says. Two years later, after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in March 2003, the number jumped to 300, the largest suicide terror campaign in history.

The Iraq War became Pape’s litmus test. He couldn’t vote for Bush again in 2004, and at one point, four years later, he was advising both Republican Ron Paul and Democrat Barack Obama, because they were the presidential candidates who opposed the war. (Obama got Pape’s vote in the general election.)

In early 2004, while Bush was still in office, the Department of Defense’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency committed $80,000 for Pape to launch a research center, initially known as the Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism, at the University of Chicago. Pape interpreted this move as the administration’s recognition that it needed help after all. That initial financial outlay, though described by Pape as “pretty tiny,” enabled him to assemble a team of native speakers of four different languages “to study more about the motives of suicide terrorists.” CPOST was born.

“He was one of the guys who we started to look to because of what he had been studying,” Hagel says. “We were very arrogant about Afghanistan and Iraq, but especially Iraq. Bob said it straight. He laid out the facts.”

Government officials apparently listened. There are fewer suicide bombings now “because we have much better policies,” Pape says. “Boots on the ground, especially in a different foreign society, is the biggest risk factor for suicide terrorism. And we just don’t do that much anymore.”

Pape’s subsequent research into ISIS’s recruitment efforts in the United States attracted the attention of Michael Morell, who served as the CIA’s deputy director and twice as its acting director under President Obama. “I found it interesting and somewhat counterintuitive that the majority of folks being inspired by ISIS here weren’t even Muslims,” Morell says. “Bob’s ISIS work showed that not allowing Muslims to travel to the United States from a number of Muslim countries wasn’t solving our ISIS problem. Our ISIS problem was a domestic problem.”

Morell says Pape’s insight that ISIS was essentially selling “the Hollywood narrative of a hero” prompted the intelligence community to devise counterterrorism measures to undermine that narrative. “The work of CPOST is very much like the work of the Central Intelligence Agency, where I grew up as an analyst,” Morell says, noting that both organizations follow the credo “Tell people something they don’t already know.” CPOST is “the only place in academia that I know of that does policy-relevant analysis,” Morell says. “There’s a lot of research that happens in academia, but the vast majority of it is detached from the real world.”

Within a week of the January 6 insurrection, CPOST was exploring the demographics and attitudes of those who stormed the Capitol. Sabreena Croteau, who’s pursuing her doctorate in political science at the U. of C., coordinated the student researchers as they excavated publicly available information — court documents, social media posts, news accounts — about everyone arrested for the attack.

What Pape and his colleagues have found is that those who attacked the Capitol were not an assemblage of rural Donald Trump voters linked to fringe right-wing groups. The movement appears to be far more mainstream than that.

The biggest surprise to Ruby was the number of arrests. “I don’t think we had any idea that the Department of Justice was going to turn this into the largest prosecution in history,” he says.

Also startling was the mob’s makeup. “This is still the big challenge for us to wrap our brains around, for law enforcement, for politicians, for society,” Pape says. “We don’t want to believe — it’s just uncomfortable to think — that that level of violence is next door.”

Less than a month after the insurrection, the Atlantic published an article by Pape and Ruby in which they shared their initial, distressing findings:

Violence organized and carried out by far-right militant organizations is disturbing, but it at least falls into a category familiar to law enforcement and the general public. However, a closer look at the people suspected of taking part in the Capitol riot suggests a different and potentially far more dangerous problem: a new kind of violent mass movement in which more “normal” Trump supporters — middle-class and, in many cases, middle-aged people without obvious ties to the far right — joined with extremists in an attempt to overturn a presidential election.

With CPOST focusing on the 193 people who by then had been charged with occupying the Capitol or breaking through barriers, Pape and Ruby reached four conclusions:

1. The attack on the Capitol was an act of calculated political violence, not mere vandalism, trespassing, or disorderly conduct that got out of control.

2. The vast majority of those arrested — nearly 90 percent — had no ties to “existing far-right militias, white-nationalist gangs, or other established violent organizations.”

3. The arrestees were older (average age 40) and more professionally established than far-right-extremist subjects studied in earlier incidents, with 40 percent owning businesses or holding white-collar jobs — a figure CPOST later updated to 51 percent after it studied more arrestees.

4. More than half of the arrestees came from counties that Biden won, dispelling the notion that the rioters lived in Trump-dominant bubbles.

“What’s clear is that the Capitol riot revealed a new force in American politics — not merely a mix of right-wing organizations, but a broader mass political movement that has violence at its core and draws strength even from places where Trump supporters are in the minority,” Pape and Ruby wrote.

For Raja Krishnamoorthi, a Democrat who represents Illinois’s 8th Congressional District in the northwest suburbs, CPOST’s findings hit close to home. During the insurrection, a bomb “was planted 200 feet from my office,” he says. He voted to certify the election’s results at 3 a.m. the next day, then took the first flight home a couple of hours later.

“I was surrounded by people in these MAGA hats and T-shirts, and I sit down in my aisle seat, and I look to my left, and the woman in the MAGA hat and shirt was scrolling through pictures of herself at the Capitol,” Krishnamoorthi says. “She was one of the ones who breached, and she was on her way to Chicago.” (At least 30 Illinois residents have been charged in connection with the riot, including 19 from the Chicago area.)

About a year later, the congressman sought out a meeting with Pape after sitting on a January 6–related online panel with him. “I’m fascinated by his work and the research he’s done, and it’s shaped my own thinking about this issue of political violence in America,” Krishnamoorthi says.

Further analysis by CPOST confirmed its initial findings — and revealed troubling new layers of the insurrection. By April 2021, CPOST had analyzed 377 Americans arrested or charged in the Capitol attack and was able to go into greater detail about demographics and attitudes. “The people alleged by authorities to have taken the law into their hands on Jan. 6 typically hail from places where non-White populations are growing fastest,” Pape wrote in a Washington Post column, noting that two independent surveys conducted by CPOST indicated that the biggest driver was “fear of the ‘Great Replacement.’ ”

“The ingredients exist for future waves of political violence, from lone-wolf attacks to all-out assaults on democracy, surrounding the 2022 midterm elections,” Pape concluded.

The picture grew even bleaker with the findings CPOST released that August. Pape’s group worked with NORC, a nonpartisan research institution at the University of Chicago, to survey 1,070 people that June and extrapolated that 8 percent of American adults — that is, 21 million people — believed both that the 2020 presidential election had been stolen and that force was justified to restore Trump to office. (When CPOST ordered a follow-up survey in April 2022, that figure dropped slightly, to 7 percent, or 18 million people.)

Jeh Johnson, secretary of homeland security from 2013 to 2017, was startled to learn that most of those arrested were not from Republican enclaves but from communities becoming more ethnically diverse — and that so many Americans would resort to violence. “You couple those two things together, and that’s an alarming statistic,” says Johnson, who discussed Pape’s findings with him on a video call.

The Biden administration also took note of Pape’s work and invited the professor to visit the White House last November. It was scheduled as a one-day meeting, Pape says, but “after the first day was over, they asked me to come back for a second day, and that was even more expansive and more detailed.” Pape declined to address the specifics of what was discussed or with whom, but he says that “the currency of Washington is time” and he found it encouraging that the White House spent so much of it with him on this issue.

In early January, CPOST marked the insurrection’s first anniversary by releasing a report titled “American Face of Insurrection.” Synthesizing information collected about the 716 arrested or charged individuals in CPOST’s database at the time, it describes “a new kind of a right-wing movement, one that is demographically closer to an average American than an average right-wing extremist and indicating that far right support for political violence is moving into the mainstream.” While the Justice Department has charged leaders of the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers — two extremist groups alleged to have planned the Capitol breach in advance — with seditious conspiracy and other offenses, CPOST confirmed its earlier finding that most rioters had no ties to violent far-right organizations.

Pape’s written testimony to the House January 6 committee, submitted in April, warned: “We are at a precarious moment in our nation’s history. Tens of millions of American adults continue to sympathize with violent insurrectionist sentiments. … A fine-grained diagnosis of the scope and drivers of the insurrectionist movement is necessary to assess the risk of political violence in the 2022 mid-term and 2024 U.S. Presidential elections.”

At the core of such authoritative diagnoses is CPOST’s exhaustive data mining. Sitting at a desktop computer in the CPOST office in March, Garcia, the student research supervisor, who is in his fourth year with the project, pulls up the template for the Insurrectionists Entry Form, crafted by Ruby. The information compiled about each arrestee includes such demographics as age, hometown, and job status. Was this person at the Capitol with family members? With friends? Is this an elected official? Someone with a criminal record? With military experience? A member of a militia or far-right group? Did the individual share social media posts or make comments to media outlets? “Of course, statements that are made prior to their arrest are particularly prized, because they’re more likely to be honest, right?” Ruby says.

Layer after layer of this onion gets peeled. CPOST is studying the role military veterans played in the insurrection, as well as family and friend connections among participants. Of the 745 people arrested or charged by early March, 117 appear to have been at the Capitol with relatives, a seemingly small percentage for a radical movement. “What we will know, at the end of the day, is how much are these preexisting networks of families and friends mattering to this?” Pape says. “It could well be far less than we’re used to thinking, and that’s important to know, because then that tells us a lot about the nature of how this radicalization is really emerging.”

What an Insurrectionist Looks Like

CPOST’s analysis of those arrested in the January 6 capitol storming has yielded some surprising results.

53%come from counties won by Joe Biden |

86%are not affiliated with extremist or militia groups |

51%are business owners or have white-collar occupations |

15%have served in the military |

Not everyone is buying Pape’s conclusions. In March, the research journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published a study titled “Current Research Overstates American Support for Political Violence.” Authored by political scientists from three universities and edited by a University of Chicago professor, it argues that CPOST’s surveys, as well as another one showing an even higher level of support for such violence, overestimate the threat because the questions don’t define “political violence” precisely enough. The results of the PNAS study indicated a lower tolerance of political violence among the general population, as well as near-uniform agreement that “suspects who commit acts of political violence” should be criminally charged. “These findings suggest that, although recent acts of political violence dominate the news, they do not portend a new era of violent conflict,” the paper states.

A CPOST survey found that 8 percent of American adults — that is, 21 million people —believed both that the 2020 presidential election had been stolen and that force was justified to restore Trump to office.

Sean J. Westwood, the article’s lead author and an associate professor of government at Dartmouth College, praises Pape’s team for providing context about the insurrectionists. “I still do worry, though, that they’re capturing more of an expressive response than a real response,” Westwood says. For instance, when respondents agree that political violence is warranted to return Trump to power, that may be their “way to vent anger about Joe Biden.”

Nonetheless, Westwood adds, although his own findings suggest less tolerance for political violence than Pape’s, the level is “not zero, so it’s still something we have to worry about.”

Pape and his colleagues say they worked to account for differing interpretations of political violence. Larson, who crafted the questions, says he had worried that respondents might not share CPOST’s definition of what would constitute force in restoring Trump to office. “It was an assumption where if it was wrong, all of our conclusions were potentially flawed,” Larson says.

So he added a question to the focus groups conducted by Cowan: “When you told us that you think violence is justified, what does that mean, exactly?” Larson says the answer came back resoundingly that “violence meant violence” — for instance, a January 6 level of force.

Despite the ramifications of those findings, it’s unclear whether CPOST’s research can remain above the partisan fray. Back when Pape was studying suicide terrorism in the early 2000s, media interest spanned the political spectrum, and he sat for interviews with Tucker Carlson on CNN and Bill O’Reilly on Fox News. Near the first anniversary of January 6, Pape says he was asked to do two interviews with far-right outlets. One was on Newsmax, which he calls “the key channel of the insurrectionist movement.” He expected the interviewer to shoot him down, but instead they had a thoughtful, thorough 35-minute discussion about the issue at hand. The only rub? “They never ran it,” Pape says.

He did another interview with a local right-wing radio station, and “within 30 seconds, they interrupted me and called me a liberal, loony academic who was at the ivory tower of the University of Chicago and was progressive, which made Keven [Ruby] laugh,” Pape says. After waiting out a few interruptions, he says, he was finally able to discuss his data and give examples of insurrectionist cases for listeners to search for on Google.

“Part of the problem in doing this kind of work is that everybody’s got an agenda,” says Croteau, the CPOST student research coordinator. “What we’re actually trying to do here is just collect and follow the data. So usually whatever accusation is thrust at us, it’s just kind of a shrug: ‘That’s what the data says.’ But in the current polarized climate, that approach is just not the norm anymore.”

It also helps to be in Chicago, far from Washington and what Pape calls the “center of the maelstrom” — and at an institution hardly considered a bastion of left-wing politics. “The University of Chicago is not thought to be the most liberal school in America,” Krishnamoorthi says, “so the fact that you have people from the U. of C. sounding the alarm I hope gets people’s attention.”

Toward the end of that CPOST gathering in March, I ask the group’s members whether their work has left them optimistic or pessimistic. They take turns answering, their verdicts split. Student researcher Maggie Mills says the broad trends make her pessimistic, but when she spends time examining each person arrested on January 6–related charges, she feels more hopeful. “They are parents and kids, and they work in their towns, and they volunteer with their schools,” she says. “This dark force is a very human problem, and these aren’t people who are inherently bad people.”

Student researcher Jack Howard is less sanguine, because the insurrectionists don’t belong to a distinct group that can be easily monitored. “If there are 21 million people who might potentially support something like this, and they’re just people living in suburbs all across the country, I think it’s an extremely difficult problem.”

After everyone else has chimed in, the boss takes the last word and makes it a rallying cry. “Why am I optimistic today?” Pape asks. “It’s because understanding motives and having new knowledge brought to bear on problems, that is the American way to solve problems. And I believe we’re doing that here at CPOST. I’ve seen it before in my lifetime. I believe this is one of the great strengths about America. This is why I’m optimistic.”

He pauses. “Although I do say that the next few years could be precarious. I do believe we will be tested.”

“We are at a precarious moment in our nation’s history,” Pape warned Congress in April. “Tens of millions of American adults continue to sympathize with violent insurrectionist sentiments.”

The CPOST students and staffers retreat to a bowling alley at the end of this long day. Pape joins them but does not bowl or stay long. “Typically at these events, as we start to bowl, he heads off, and the rest of us get to enjoy that time together,” Ruby says.

Three months later, on June 7, Pape is testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee after the mass shooting in Buffalo. The gunman who killed 10 Black people with an assault rifle at a supermarket in May had cited the great replacement as his justification. Pape, invited by committee chair and Illinois senator Dick Durbin, zips through a detailed slide presentation that connects the attack to “the rise of violent populism” and highlights CPOST’s insurrectionist findings.

Pape asserts that right-wing media figures and politicians have boosted their popularity by pushing the great replacement theory, and he evokes former Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic, who laid the groundwork for war and genocide in Bosnia with his warnings that Serbs were in danger of being replaced.

Afterward, while in a taxi to Reagan National Airport, Pape says he’s pleased with how the hearing went. “They gave me a chance to lay out the data,” he says. “That’s a very big deal.” Even conservative Republicans such as Texas’s Ted Cruz and Utah’s Mike Lee didn’t directly dispute any of his points.

“What makes America great is we can still have events like this morning where a professor from Chicago, who has highly reliable information that bears directly on one of the most controversial issues of our times, gets a hearing on both sides,” Pape says. “We’re actually slowly, slowly having the beginning of a national conversation.”

The taxi arrives at the airport, and Pape requests a receipt. Eight days later, he will be back in D.C. The White House wants another meeting to discuss the domestic terrorist threat, and he has some thoughts.