Helmut Jahn died without knowing the fate of his polarizing masterpiece, the James R. Thompson Center. How much longer will it stand? Just five days before the architect’s death in 2021, Governor J.B. Pritzker issued the state’s request for proposals for the sale of Jahn’s long-embattled Loop landmark — without any stipulation that it not be torn down.

With its soaring 17-story atrium, the curved glass building, which initially housed state offices, nodded to the domed structures of classical civic structures and symbolized a desire for transparency in government. During the grand public unveiling in 1985, officials unfurled a banner declaring it “A Building for Year 2000,” a sign of optimism for Illinois’s future and Chicago’s legacy of boundary-pushing design. But years of deferred maintenance and political ambivalence eventually took their toll, and the Pritzker administration estimated the cost of necessary repairs and updates at more than $325 million.

Preservationists and admirers worried the Thompson Center would be demolished. Jahn shared that fear, and in 2016 he drafted an ambitious proposal to repurpose the building by adding a 110-story tower featuring a hotel, residences, and office and retail space. He seemed barely able to process a reality in which one of his proudest creations might cease to exist.

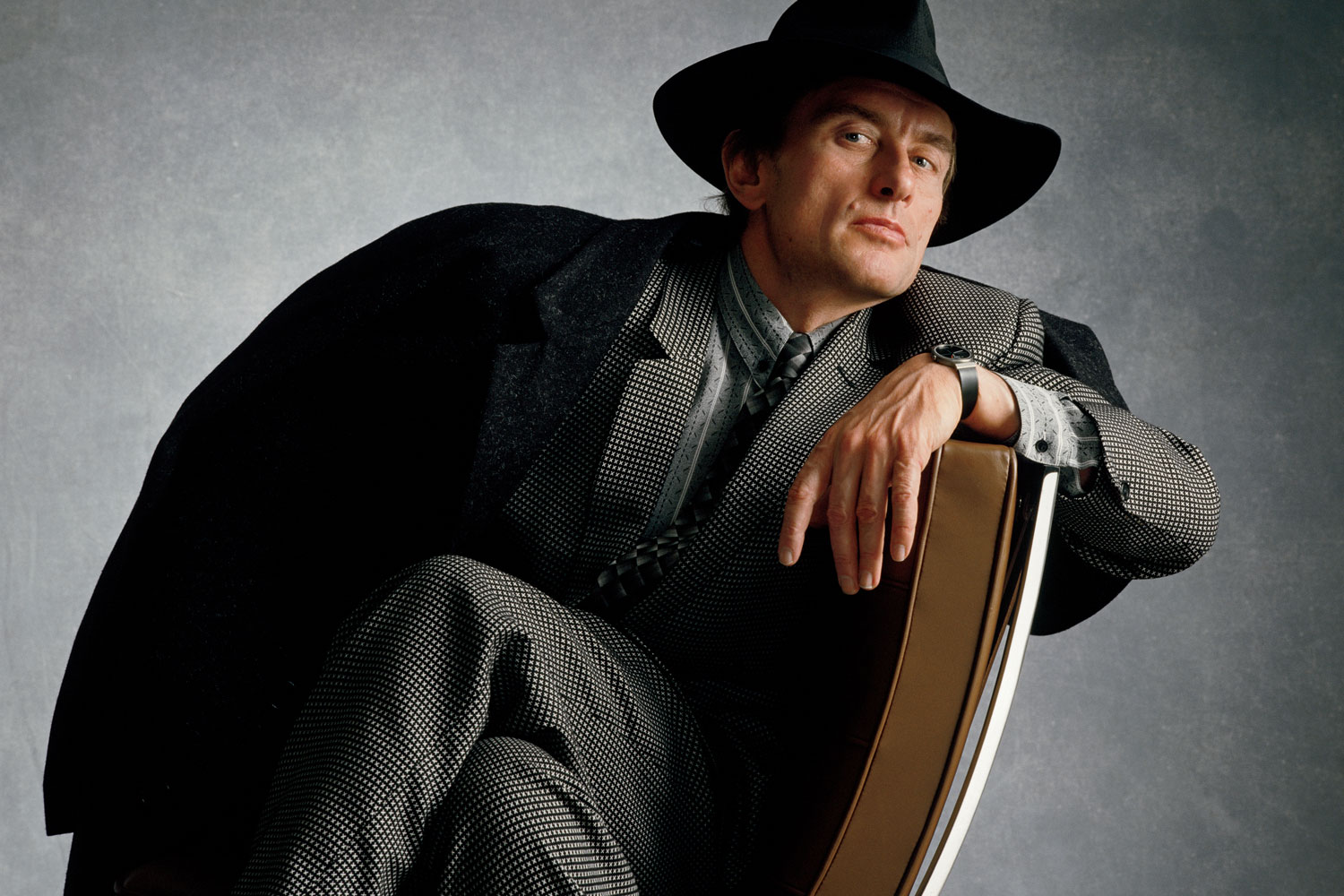

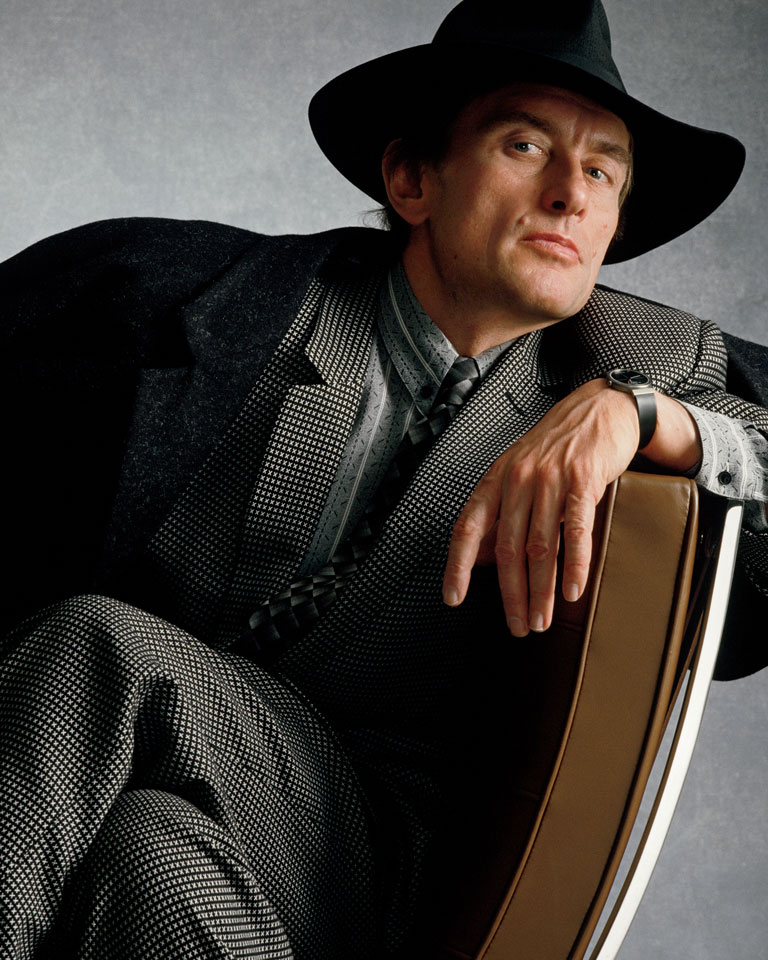

“I think about it, but then I say, ‘I can’t go on this street,’ ” the dapper German-born architect said in an interview at his firm’s office, then located within the Loop’s historic Jewelers Building. “I imagine I would stand in front of the building with a [protest] sign.” He summoned the memory of Chicago architectural photographer and preservationist Richard Nickel, who was killed in 1972 when a portion of Adler & Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange Building collapsed on him as he was salvaging fragments during its demolition. Losing one’s life trying to save a building — to Jahn it was an honorable death.

He expressed this during the second of our three interviews conducted in May 2018, July 2019, and October 2020 and almost entirely unpublished until now. The idea had been to compile conversations with Jahn and his Thompson Center collaborators into an oral history of the endangered building.

But seven months after the last interview, Jahn was riding his bicycle a few miles from his home in the western suburb of St. Charles when he was killed in a crash involving two vehicles. He was 81. When Jahn died, so too did the momentum for our story. Though his professional legacy still seemed tied to survival of the Thompson Center, the sudden absence of the creative force behind the structure — the man known as the “Flash Gordon of architecture” — was deflating. Elvis had indeed left the building.

Then came renewed hope for the Thompson Center: In July 2022, Google announced it would purchase the structure for its Chicago headquarters. The tech giant is working with Jahn’s firm, now headed by his son, Evan, on renovations, which began in May and are expected to be completed in 2026. The innards are getting overhauled, but from the outside, the building will still look like the one its fans know and love.

This latest infusion of energy into the Thompson Center sent us back to our shelved interviews with Jahn. Not unlike Nickel, we dug through the ruins in search of treasure — and we found it. Jahn’s words, presented here, now speak to us from across the veil, describing the creation and early promise of the building, his despair at seeing it fall victim to neglect, and what he believed needed to happen for his marvel of structural expressionism to have a life beyond his own.

III

III

I never asked Governor [James R.] Thompson about it directly, but I think the decision to give me the Thompson Center job had to do with the fact that he didn’t want an established firm like Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. He wanted somebody who was new and becoming known.

III

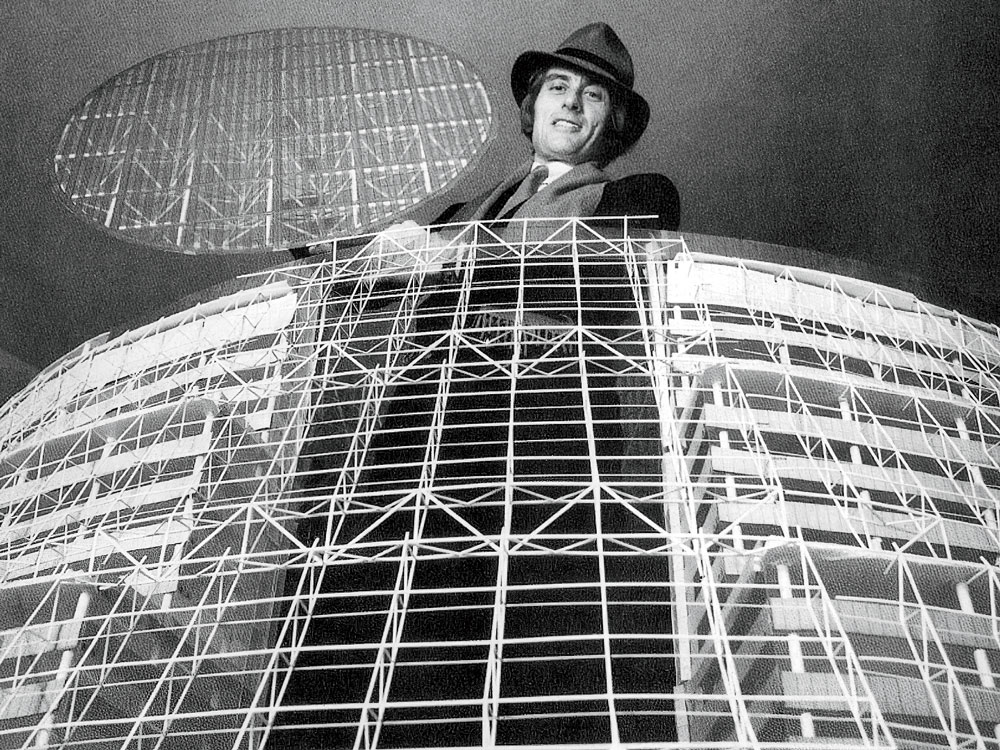

The state always wanted a high-rise building. But a high-rise on that site would’ve gotten lost. That’s why I ultimately gravitated to the urban block design, with the rotunda and the dome, reminiscent of the old government building on the Federal Building site at Dearborn and Adams by Henry Ives Cobb. That’s where the idea came from.

III

I had three different schemes that I presented. I was not allowed to favor one. I was asked to leave the room while Thompson and the state officials debated the designs. There was someone I knew very well named Brian O’Connor, who was working for the state development agency as the project manager. He said, “Well, Governor, now we’ve gotta pick one.” Thompson said, “What one does Helmut like?” And Brian said, “This one” — the one that ultimately was built. And Thompson said, “Well, I wouldn’t have picked that one, but Helmut must know why.”

III

And that was it. I wish things would be so easy these days. I was extremely happy, because if he would have picked the high rise, I would have gone back to him and said, “I don’t want to do this,” because the idea with the Thompson Center to merge public space with retail and the activities of the state — it’s an idea you can’t do with a high-rise building. A high-rise is a commercial building.

III

When the building was designed, and we had built a big model, this was during a time when [Chicago-based architect] Stanley Tigerman was doing a series of talks with renowned architects. They were all there at the University of Illinois’s Circle Campus: Philip Johnson and Peter Eisenman and Michael Graves and Tigerman, and then there were younger guys like me. Johnson said to me, “How are you doing on this state building?” I said, “Do you want to come to my office? I’ll show you.” The big model was in the photo studio, and we walked in there, and Johnson said, “Wow!” Tigerman said, “This isn’t a postmodern building.” Because the building was, like all my buildings are, about the integration of architecture and engineering, the integration of urban space, the breaking down of barriers, making a symbolic statement about the openness of the government.

III

I remember the opening day of what was then known as the State of Illinois Center. It was 1985. My son was 3 or 4 years old, and he played with Governor Thompson’s kids while we did the speeches and the ribbon cutting. Certain things I remember very well, like the big sign that said “A Building for Year 2000.” Halfway through the ceremony, my son came up to my wife and said, “Mommy, I gotta go pee-pee.”

III

The initial problem with the Thompson Center was that the mechanicals were miscalculated. The idea was always that heat rising in the atrium would be drawn into a vent. But there was a misjudgment in terms of the air being pulled out of the atrium correctly, so hot air filled the atrium and moved into the floors. One thing I was always against was the state’s insistence that the cooling — somebody put this thought into their heads — would be done by ice. It was a gimmick to use cheap electricity at night to make ice and blow air over it during the day. I said, “It’s never going to work.” Through overexposure to sunlight, the rooms would get very hot, the ice would melt by late morning, and there was no cooling effect. There are a lot more efficient ways today to air-condition a building.

III

After Governor Thompson came Jim Edgar, who somewhat still cared about the building. But he wasn’t very long in office. After him, it was just neglect.

III

The building has become a bad mark in the cityscape. You walk by and you look at the rusted column covers and no maintenance of the landscaping and they haven’t fixed those stone pieces on the lower part of the building. They took all the stone away for no reason — just because a couple stones fell off. This is criminal. This is a bunch of idiots.

III

Watching the Thompson Center fall into disrepair over the years, I’ve felt — “angry” is not the right word. It makes me sad. My son has two young girls, and they wanted to see some of my buildings. So during Christmastime we went there. It was a Saturday, and the building was closed. It’s supposed to be a public place. When I said, “I’m the architect,” the guard got all friendly, wanted to take a picture with me, and gave us a tour. My son said, “Dad, this is really sad.” The carpet in the walkways is 30 years old. It looks like asphalt, it’s so dirty. You don’t even want to put your shoe down on it. That was the last time I was there.

III

The Thompson Center is more than 30 years old now, and there’s a lot of change in building technology — mechanical systems and stricter codes in terms of how we use the energy consumption of the building. A lot of public buildings that have been repurposed — they have come to a new life. I think that’s what this building needs. It needs a new life.

III

There’s a history of my buildings being repurposed. Real estate investment companies buy the building, fix it up, and sell it. The Kemper Arena in Kansas City, Missouri, has been repurposed. Somebody bought it, put extra floors in, and it now has 20 basketball courts and different things. The Messeturm “pencil tower” in Frankfurt, Germany, is owned by Blackstone. We are working on redoing the main lobby and some of the floor lobbies. This is costing $80 million to $100 million. The lobby is going to be more active, with a coworking space, a bar, a restaurant that changes from morning to night, and an exhibition space. The Sony Center in Berlin has been bought by Oxford, which is the codeveloper of Hudson Yards. They spent $1.2 billion. The building was only just finished in 2000. It’s not that the building, in this case, has any problems. It’s that they want to change the tenancy. They rented to Facebook, WeWork, Google.

III

It may seem like I have been fairly quiet about the Thompson Center being threatened. But to get out into the public and create a controversy — that’s not going to bring anything positive. Instead, I did the work to show repurposing the building is very feasible, that it could be a hotel and an office building and apartments. When I showed the architect and structural engineer Werner Sobek my proposal, he said, “It looks like it’s always been there.” My hope is that when the request for proposals comes out, they will contact me. I hope somebody is not going to propose to tear the building down.

III

My idea is to make the atrium open. No doors. Anybody can go in there. You can be outside. This could be something you can go and see at the center of the city.

III

The best outcome is that you find somebody who gets the building away from the state and does the most responsible thing in terms of upgrades and repurposing the building. The building is an iconic one and nobody can deny it.

III

Somebody once told me, “If you tear the Thompson Center down, you would have to do something that the whole world would talk about.” Hopefully there are some people with their right and conscious mind who will say tearing the building down is not going to solve the problem. At this time, this location is not where anybody wants to build a three-million-square-foot building. You don’t build these monsters anymore. And if you build multiple smaller buildings on the site one at a time, it’s going to take just as long as Block 37, which took 25 years and ended up in a real mess. The easiest thing would be to fix up the Thompson Center. And the best chance to save it is to repurpose it into a tech loft space.

III

How the Thompson Center Got Its Big-Screen Moment

Shortly after the completion of what was then called the State of Illinois Building, the 1986 buddy-cop film Running Scared thrust Jahn’s eye-popping edifice into the Hollywood spotlight. (“I’m not a movie guy,” the architect told me in 2019, “[but] I’ve seen parts of it.”)

Director Peter Hyams recalls how he came to shoot his climactic scene there:

Running Scared grew out of a love affair I have with Chicago. From 1968 to 1970, I was a blissfully untalented anchorman and reporter for CBS-2. One of the things I felt about Chicago was that it was visually spectacular — more so, actually, than New York. Chicago has the elevated train going right through the city. The original script was about two New York City cops who retire. I said, “I’d like to change it to two Chicago cops who don’t retire. And instead of two elderly guys, I want Billy Crystal and Gregory Hines.”

I wanted to use the city as much as possible. And while we were scouting locations, I saw this building downtown. I went, “What is that?” The person from the Chicago Film Office said, “It’s the State of Illinois Building. There are some people there, but it’s not totally open yet.” I said, “Can we get in there at night?” That building, to me, engenders acrophobia. Just go inside and look up. It’s the fact that it kind of slants inward. It has a vertigo quality to it. That’s why I wanted it.

What I asked the film office for was not easy. I wanted to have a guy coming down from the roof into the atrium on what’s known in the stunt world as a descender. But we got the go-ahead to do whatever we wanted, including taking a panel of glass out of the roof. I said, “Holy shit!”

The stunt people, at one point, didn’t want to do the stunt. So we had the building’s window washer do it. To him, it was like a walk in the park. To me, it was absolutely horrifying. — As told to J.M.