As the granddaughter of a Spiritualist churchgoer, Ayana Contreras must have heard sermons inspired by the verse in Ezekiel that asks, “Can these dry bones live?”

In the Black church, that passage of scripture is invoked frequently as a reminder that even people and places that seem damaged, abandoned, and crumbling can be made new, whole, and beautiful. It’s often how you look at a circumstance, believers are taught, that can determine its meaning.

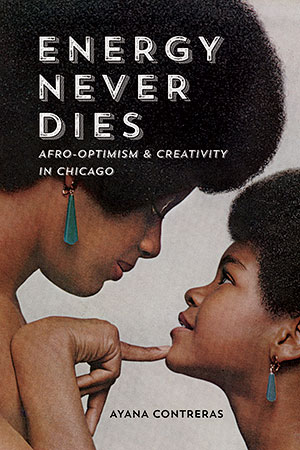

In her new book, Energy Never Dies: Afro-Optimism & Creativity in Chicago, Contreras looks beyond the despair that grips the South and West Sides to grasp the too-easily-forgotten tales of Black excellence. Her book can be viewed as a memoir, historical study, and self-improvement workbook combined into a narrative that unfolds with jubilant flair.

In many stories of Black resilience, African Americans must overcome systemic obstacles to find success. So often, Black people are expected to rise above poverty, indecent housing, hunger, and racism to gain the signifiers of achievement. But rarely do these stories center on Chicagoans.

This is where Contreras excels. Mining her many hours of interviews with local Black tastemakers, cultural innovators, and architects of cool, Contreras captures how they directly and indirectly influenced one another with their work. She explores how the generations build upon the foundation laid by their predecessors. Black Chicagoans are interconnected like a web, with fine threads woven together to form one shape, one body.

In Contreras’s Chicago, a Black restaurant owner isn’t just a chef with a winning barbecue sauce recipe. Argia B. Collins created Mumbo Sauce and a barbecue empire. But he also used his business to build an alliance within the Black community and even bankrolled a soul singer’s stint at the Chicago Conservatory of Music. Collins was devoted to investing in the community and uplifting social causes. And in exchange, his sauce was a staple in a multitude of Black households loyal to his brand.

Contreras reminds her readers that the members of Earth, Wind & Fire were more than just genre-defying musical titans who created a soundtrack for a new generation. Throughout the band’s rise, they continued to tap into a collective of innovative local artists to keep their sound fresh.

The Reverend Jesse Jackson may have popularized the phrase “I am somebody,” but Contreras takes readers back to the poem from which these words come and then ties it to a song performed by a Chicago soul group.

Contreras connects the success of Black Chicagoans to how most of them got here: the Great Migration. She writes that those migrants had a unique drive combined with “a certain Southern sensibility and flow” that they used to propel themselves forward. That energy, that spirit, never dies, Contreras’s grandmother told her. Contreras uses this notion to explain how Chance the Rapper and other contemporary local celebrities are extensions of that original Black Chicago electricity.

Her narrative is illuminating because the stories celebrate how the community, and the city itself, are a thread tying the people and their journeys together.

Contreras is best known as a radio host at Chicago Public Media’s Vocalo and a DJ at the CTA’s 95th Street Red Line station. But with this book, she firmly establishes herself as a scholar deeply knowledgeable about the city’s Black history and steeped in the music and sounds that originated here.

Contreras’s tale is “so Chicago” that I found myself wondering about her target audience. Reading her stories feels like listening to house music in the park on a hot summer day. For those of us living in the city, especially in the communities that have been historically neglected, Contreras’s writing is a mood booster. Her reflections on the past help a younger generation of Chicagoans learn where they are from and who they belong to and encourage reaching for ever higher goals.

Yet this book is also mandatory reading for the growing number of outsiders gazing upon our city. Stories of the interconnected lives of our artists, activists, and clergy unfold from Contreras naturally, in part because so many of them form her destiny. When she stumbles on a vintage album, it’s not just a treasured find for a music lover; it’s a portal into a rich story and a confirmation for Contreras that she is where she is supposed to be, walking in the path set before her by her ancestors.

Rather than being driven by the question of how these generations of intrepid and visionary Black Chicagoans managed to build themselves a promised land, Contreras’s stories are layered with answers to the questions we forget to ask. I like to think of Energy Never Dies as a fact-driven expansion of the Nikki Giovanni poem “Ego Tripping.”

I can understand why Contreras avoids broaching redlining, stubborn segregation, the persistent racial wealth gap, and structural disinvestment. Those topics have all been thoroughly examined in so many other books and too often cast a shadow on the success stories that emanate from Chicago.

Still, I think her narrative could have used some of that context, if only to demonstrate just how audacious and brilliant Collins, and Jackson, and Chance, and the others who rose to incredible heights really are.

But even without those dreary statistics as a backdrop, Contreras’s Chicago is a place where the dreams of the driven come true.

Her world, elaborately described with poetic language, is not only a nice place to visit but one where those of us who envision a brighter and better Chicago must take up residency if we want our visions to become manifest.

Can dry bones live? Contreras’s answer is a resounding yes.