The mystique of Vivian Maier, the reclusive Chicago photographer/nanny who found posthumous fame, shows no signs of losing its grip on the cultural imagination (see: Vivian Maier: In Color at the Chicago History Museum through May 2023).

But a new biography by first-time author Ann Marks — who became fascinated by Maier after seeing the 2013 Oscar-nominated documentary Finding Vivian Maier, produced by John Maloof, Charlie Siskel, and actor Jeff Garlin — suggests that a lot of what we think we know about Maier may be wrong. In Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny (Atria Books, December 7), Marks dived into exhaustive genealogical research, analysis of all 140,000 of Maier’s extant images, and other personal records to offer a portrait of a woman who “overcame tremendous family obstacles to lead a full, satisfying life on her own terms.”

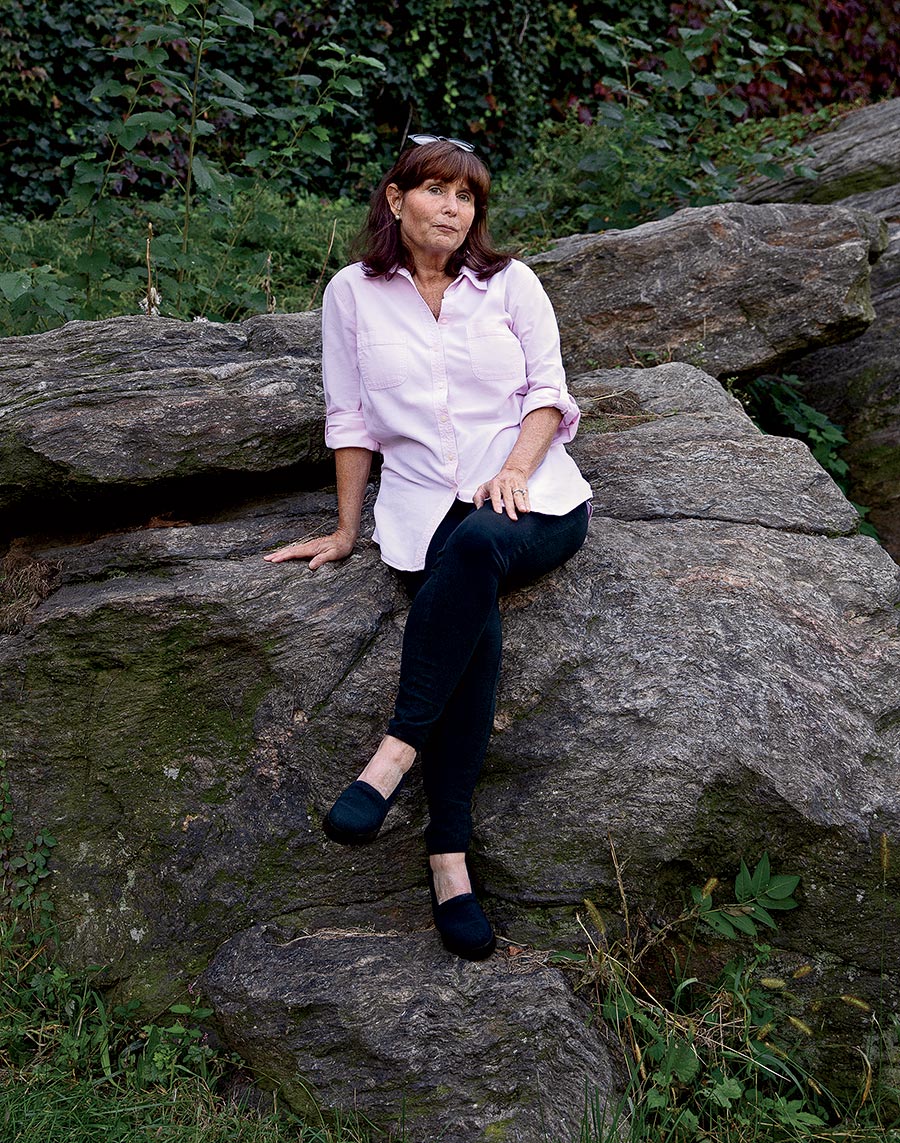

We caught up with Marks, a retired chief marketing officer of Dow Jones and the Wall Street Journal, by phone to talk about some of the insights she uncovered. The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Was there a particular aspect of Maier’s life or work that initially piqued your curiosity?

There were two things after I watched the documentary that I couldn’t stop thinking about. One was all the different adjectives that everyone used to describe Vivian. In the book, I kind of start off with that because they’re just such opposites. Some people thought she was nice; some people thought she was mean. Some thought she was old-fashioned; some that she was feminist. It was just completely contrasting descriptions. And I thought: How could I make sense of this? Why do people have different perceptions? And then the second thing was, I just couldn’t believe in this day and age, with all the digital records, that all these genealogists used their skills and time, and John and Jeff used their money to find out anything they could about Vivian, and they kind of turned up a little bit empty. I thought that there’s something so strange about that, and I felt like I needed to crack that, because everybody has a family, and I needed to find out where they were.

How long did it take for you to find that all these dichotomies really did come from a deep, tangled family history?

I spent about five years on the research, and then two years getting published. Everywhere I went, I found really interesting things, and then I sort of was able to unravel the whole family story and the France story. [Many believed Maier was born in France, but in fact she was born in New York.] I was able to find people in New York who knew Vivian, which was a huge part of cracking her story, because she was like a different person there. And that’s when she started photography. In fact, I ended up finding that her whole attitude about photography, her behavior, was completely different in New York. And so it really opened up new learning about her for sure.

What specific things made you understand that the popular narrative around Maier — including the idea that she never wanted to exhibit her work — was not necessarily the correct one, or at least the full one?

I uncovered some key things pretty early on. There was a reason for her to be secretive about her life. It wasn’t because she was an oddball eccentric. She had a really bad family life, and there was no benefit to her in telling these upscale families in Highland Park [where Maier worked as a nanny] that her father was an alcoholic and he was violent and her brother was in jail and in institutions and her mother was a narcissist. Her whole story was painful enough, but you would never want to expose it to other people, especially if you would be watching their children. So I find that her behavior was actually rational, when a lot of people thought it was very strange.

Talking to people in New York really changed everything, because it became very apparent to me that she did try to be a professional photographer. She was very open with her photographs. There’s one family in New York that has hundreds of vintage Vivian photographs. In Chicago, she’d give people like two at the most. So she was much more generous and open with her photography in New York. The aftermath of her traumatic childhood caught up with her, and it really changed her ability to share her photographs. You could very much argue that she’d wanted to be a photographer and show her work and was proud of her work and would have been just fine with what’s happening now.

What was the most profound discovery in all the research that you did that perhaps you hadn’t expected to learn?

There were a number of aha moments, but the biggest was when I listened to her tape recordings. Because I had a perception of Vivian just based on how people described her — even with the contrasting adjectives, you feel like there’s kind of a seriousness, a detachment. You just get a vision of what she was like. Well, when you listen to the tape recordings, she’s nothing like you think she is. And I realized that everybody’s perception was based on her physical presence, which could be off-putting, but she was actually warm and patient and nice and nothing like what we’ve come to think about her. So I just looked at her in a whole new light, and that’s when I really wanted to understand why she appeared the way she did, why she presented herself the way she did, who was the real Vivian, and how was that expressed, then, through her photography.