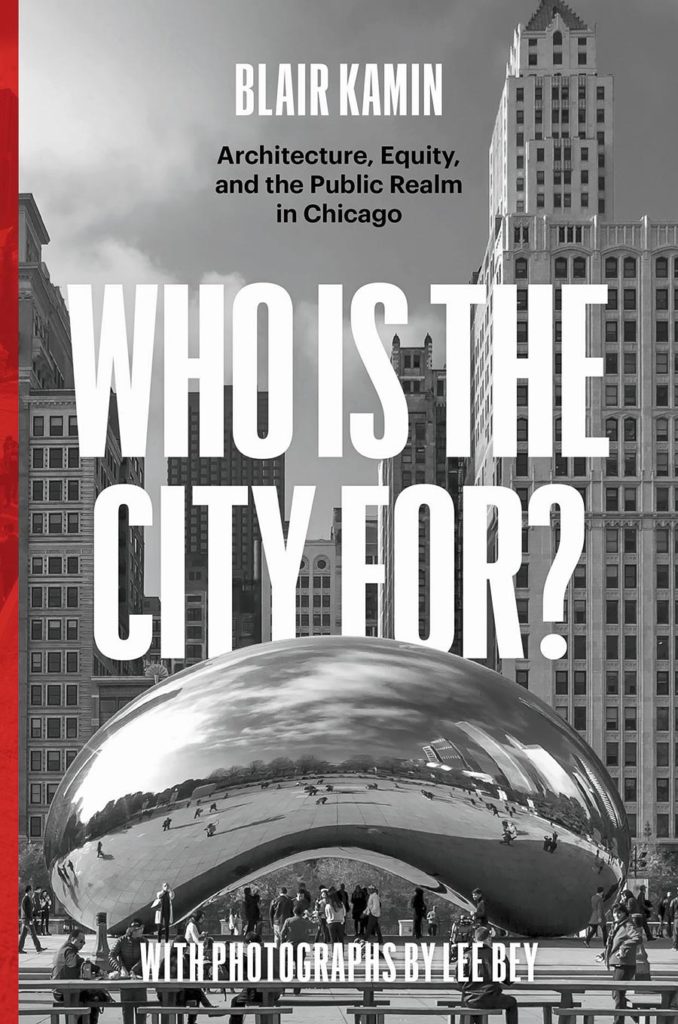

It is divinely inspired that the spine of former Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin’s new collection of essays is red and bleeds slightly onto the front and back covers. On the book’s front is a photo of Cloud Gate, the Anish Kapoor sculpture in Millennium Park popularly known as the Bean. The back cover has an image of Emmett Till’s former Woodlawn home. The red line of the spine dividing them serves as a reminder of the policies, legislation, and rules that have kept Chicago racially and economically separated.

In Who Is the City For? Architecture, Equity, and the Public Realm in Chicago, Kamin, with the support of photographs by Chicago Sun-Times architecture critic Lee Bey, probes just who Chicago serves and how the city can be reshaped and reimagined as a space for all its residents.

Blair, this book is your third compilation of columns. How did the idea of you and Lee working together come up?

Kamin:We have this deep reservoir of competition but also compatibility. In the 1990s, Lee’s big crusade was Bronzeville. He was hammering Mayor Richard M. Daley every day. It was groundbreaking work because it was spotlighting an area of the city that the powers that be had ignored and that had great historical value both to African Americans and to the whole city. Similarly, I did a series on the lakefront, and the most important piece pointed out the lack of equity between the north lakefront, lined by affluent white neighborhoods, and the south lakefront, mostly lined by poor Black ones. Both of us had major projects that had to do with equity. Both of us always stressed that architecture criticism is not just about buildings or theories or who is hot and who is not — it’s about people and how designs affect them.

Who are you targeting with this work, which is specifically focused on Chicago?

Kamin:It’s mainly intended for a Chicago audience, but Chicago is the great American exaggeration. It shows, it symbolizes, and reveals issues that pertain to all American cities. The issues that Chicago faces with inequity, lack of housing affordability, crime, a downtown that’s booming and outlying neighborhoods that are withering — those apply to nearly all American cities in different ways.

Bey:You could break the audience down in many ways: people who care about cities; people who care about architecture; people who care about the future of cities. No matter where you live, whether it is Louisville or Brooklyn, you are struggling with the same issues.

When we think about Chicago, we tend to trumpet the connections to Barack Obama. But this book highlights Donald Trump’s relationship with Chicago too. Why go there?

Kamin:I picked Trump and Obama basically because it’s a sexy juxtaposition. The Trump sign controversy was a crazy, hilarious story that generated national attention. It also foreshadowed Trump’s demonization of the press. Because when Trump wanted a great review, I was a great guy. Once I said the sign was an eyesore, I was a third-rate critic. At the same time, it was interesting to pair him and Obama because there are these two presidents and they both have big projects in Chicago. I tried to be tough on both sides of the political aisle. Obama didn’t get a pass when he unveiled his presidential library. I pointed out things that I thought were good about the plan, the way it might improve Jackson Park. But I also was pretty tough on the initial design because to me it looked like Pharaoh’s pyramid updated: It was squat, it was monolithic, it was forbidding. And they changed it, perhaps in response to that critique.

Bey:The Trump-Obama juxtaposition was one of the things that sold me as a photographer on being part of the book. It frames the decade timeline perfectly. On the Obama side, I wasn’t a fan of the tower. I wasn’t a fan of the stone design. But now I want to see more of the project, I want to see it come out of the ground, and I want to judge the building once it’s complete.

This collection centers a lot on equity and the way investments have been focused downtown and the way South and West Side communities haven’t benefited.

Kamin:Equity is a desirable thing, but it is not a simple thing. Equity, for many people, wasn’t just about the economic development associated with the Obama Presidential Center, it was about preventing the gentrification that the center threatened to bring to Woodlawn. Or it was about ensuring that people who live on the South Side would gain economic benefits — not just indirect but direct from the construction and things like that. We think of equity as being fair treatment of the areas that have always gotten the short end of the stick. But equity has many different dimensions, and sometimes those dimensions are in conflict.

Both of you have mentioned the lack of architecture criticism today and that it is a dying beat. What does that mean for you and for Chicago to have architecture criticism in peril?

Bey:It’s such a complex question. I wrote the book Southern Exposure, which came out in 2019, and it came about unconventionally. I was vice president of the DuSable Museum, and Northwestern University Press had an acquisition editor who liked my photography and asked if I had anything I wanted to put in a book. I just happened to be doing an exhibit on South Side architecture. After that, I realized I had more to say about these topics, so I said, yes, I’ll rejoin the Chicago Sun-Times. That’s not how news outlets should get an architecture critic. There ought to be an understanding in the newsroom that in a city like Chicago especially, the architecture is everything. We are all talking about it. It is what knits us together, just like sports, the weather, and politics.

How do you want this book to move people?

Kamin:I hope it reminds everybody that as we think about electing a new mayor, that ending gun violence — as important as that goal is — is not the only issue that matters. Building an equitable city — a city that has infrastructure, schools, parks, transit, housing — is a hugely important goal. Because if you have a healthy city that gives opportunities to people who have been disadvantaged for decades and who have been hammered by disinvestment and other structural inequities, if you do that, you’re going to have a healthier and less violent city.