For nearly two decades, Erick Williams was the respected executive chef at MK. Working under chef-owner Michael Kornick, he helped to relate a story of farm-to-fork dining in the way it was oft told, with an American perspective superimposed on a classical European framework. But it wasn’t until he opened his own restaurant, Virtue in Hyde Park, that Williams hit the big time in terms of national recognition. Here, the native Chicagoan told a culinary story from a more specific point of view, that of Southern cooking through the lens of his Black forebears and the Great Migration.

Many chefs open restaurants to share their personal outlooks, and many are fine cooks. Yet few have achieved Williams’s level of critical and popular success, which includes a James Beard Award and a full-to-bursting reservation book. The reason for his triumph is not simply that he told his own story — it’s that he’s a gifted storyteller. As he explained to me, he aims to create the “kind of establishments that provide culture, clear narrative, and unmanipulated delicious.”

Now Williams has turned the page on a new chapter. Actually, two new chapters. In late 2021, he opened the carryout-only Mustard Seed Kitchen in the South Loop, bringing affordable scratch-made meals to an underserved area. Its name, you may know, references a Bible verse about the power of faith, and the restaurant furthers the work he began in 2020 of combining community service with entrepreneurship. Then, in August, Williams followed up with Daisy’s Po-Boy and Tavern, located just around the corner from Virtue. Here, Williams isn’t just telling the story of Hyde Park — he’s writing it. In his mind, this diverse and complicated neighborhood is a place where people who’ve come from around the world for the University of Chicago and people who’ve lived nearby for generations can and should unite to celebrate Black culture. What better way to do that than over a bowl of gumbo and an overstuffed po’ boy?

As at Virtue, Williams brings a Chicagoan’s perspective to the menu. Daisy’s isn’t so much a trip to New Orleans as an ode to it. As befits our cold climate, the soups and gravies are thicker, the condiments are slathered on with more abandon, and while the seafood is good, the meats are better. But after two visits, I can attest that Williams also brings the unmanipulated delicious.

The space in the Harper Court development (formerly Jolly Pumpkin Pizzeria & Brewery) is an open box but a delightful one to roam your eyes over. Colored lighting fixtures create a knowing, lived-in glow. Natural wood paneling, self-service water and silverware stations, framed faces from Mardi Gras krewes, green-checkered tablecloths, TVs just waiting for the LSU game — it all gives this new space an old soul.

As many good restaurants today are learning, fast-casual service isn’t just for burrito bowls anymore. So you line up to order at the counter, and if you just want to get a round of classic Southern cocktails, a couple of apps, and a number for your order, you’re free to park at a table and wait for friends. Daisy’s excels with this part of the menu. I was thrilled to find a favorite beverage, Chatham Artillery Punch, and even happier to have a basket of fried boudin balls to snack on. The bar also makes a respectable Sazerac that just barely hints (as it should) at anise, and a sweet, boozy frozen Hurricane that’s hard to say no to.

I wasn’t a fan of the debris fries, as the roast beef topping was cubed rather than shredded and the gravy floury and stodgy. But the Voodoo Wings, slathered in ruddy hot sauce, had me twisting those flats for every bit of meat and skin until there was nothing left on my plate but a pile of bones. I asked Williams about his stupendous sauce recipe, and he quickly credited it to Brian Jupiter of Ina Mae Tavern in Wicker Park, who “gave me a note or two.” I mean … wow.

As far as the signature po’ boys — which range from fried seafood to roast beef and even fried green tomato — Daisy’s gets a solid B from me. Williams brings in Leidenheimer rolls from New Orleans, which are the perfect vehicle for po’ boys because they have a thin crust that crackles with fissures like a parched desert floor, and a pliant crumb that compresses to make room for its heaped filling. Perhaps because the product takes a day or two to get here or perhaps because the cooks haven’t yet gotten the art of wrapping the sandwiches, the rolls don’t quite hug their contents or offer that mouthful of crunch and cotton. That note aside, these sandwiches, piled with lettuce, tomato, bread-and-butter pickles, and a thick slather of mayo (or rémoulade for the fried catfish), are tasty. I’m a sucker for fried oyster po’ boys, but the stealth winner in my book was the one filled with spicy housemade sausage patties. Only the Peacemaker, containing an unhappy marriage of fried oysters and roast beef, didn’t do it for me.

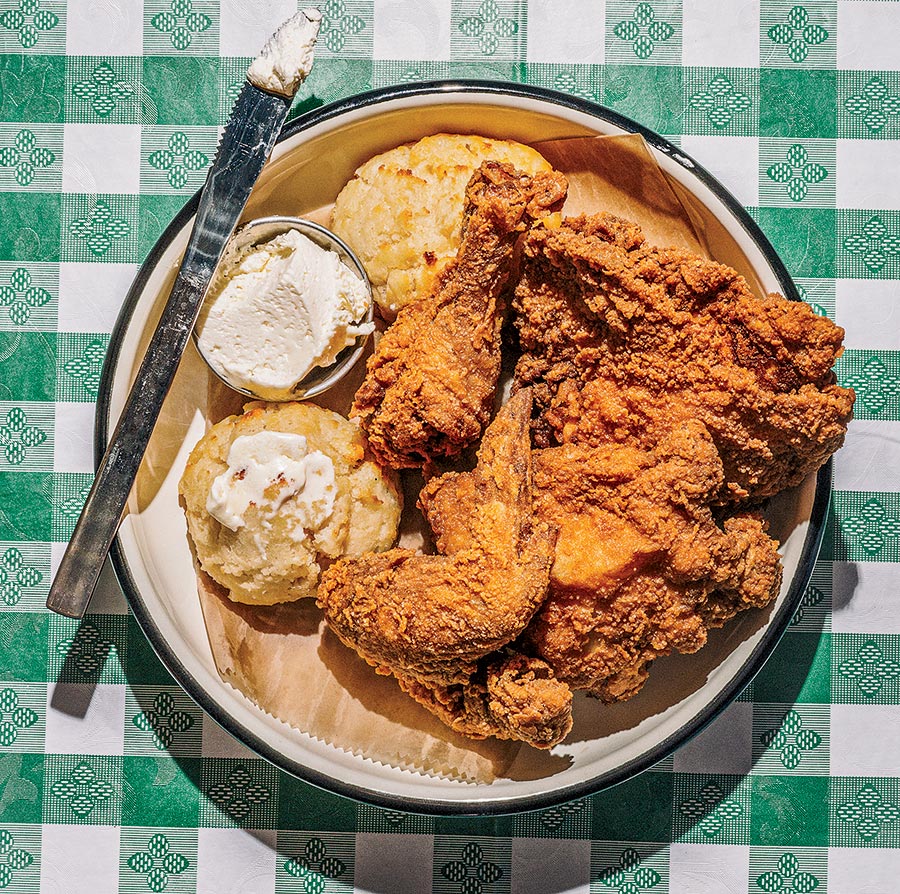

Daisy’s also offers extra-crunchy fried chicken that Hyde Park residents should bookmark for carryout, and a stupendous plate of fried catfish that’s as crisp, clean-tasting, and steamy as any you’ll find. There’s a muffuletta that’s been Chicagoed up with giardiniera subbing in for olive salad (no comment) and a thick seafood gumbo that Williams says is typical of cooks in the North who like it “closer to gravy.” Cooking with a sense of place can be a complicated business.

Williams credits his inspiration to his great-uncle Stew, married to his aunt Daisy, who had family roots in Louisiana and was an excellent home cook. That’s the part of the story he likes to tell. The part that goes unsaid, perhaps, is that this uncle showed an impressionable young boy that cooking was a noble métier for men. Wherever fate would take you and your family, your culture was a bowl of gumbo away.