The main entrance to the once-gleaming Arlington International Racecourse, where bettors spent big money on the “sport of kings,” is now a destination for drivers of U-Hauls, delivery vans, and small trucks. They’ve come to cart off the last remnants of the 95-year-old track — chairs, wooden benches, kitchen ovens, bathroom signs, betting kiosks, and even horse blankets, all purchased in online auctions, some with bids starting at 50 cents.

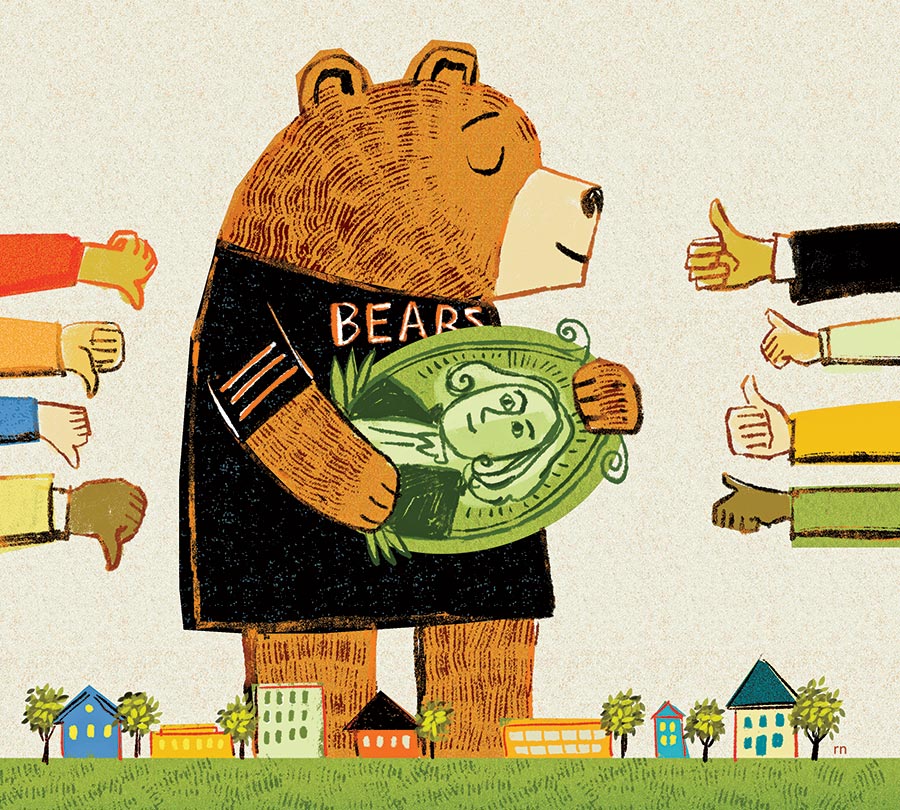

This fire sale was ignited by last year’s agreement by the Chicago Bears to purchase the 326-acre site. The team’s game plan calls for building an estimated $3 billion stadium and an adjacent entertainment, recreational, commercial, and residential complex — one of the largest in state history. The entire venture could cost up to $5 billion and take more than a decade to build.

“It’s absolutely a once-in-a-lifetime development,” gushes Thomas Hayes, mayor of Arlington Heights, which would be home to the stadium. “There’s no greater opportunity for this community and the northwest suburban area.”

“This is a global opportunity,” echoes Joe Gallo, mayor of Rolling Meadows, which borders the proposed site. “It will have tremendous impact on attention and awareness of the region.”

It’s easy to see why they are excited. In addition to the eight or nine Bears home games every season, the team has floated the prospect of the stadium hosting a Super Bowl, college basketball and football playoffs, industry conventions, and concerts — which means crowds for hotels, restaurants, and other small businesses in the area. And the covered arena the Bears are planning would allow for events year-round. Plus, there’s the publicity value of having your town mentioned on national TV broadcasts.

But how much would all that cost taxpayers? While the Bears vow to pay privately for the stadium, they are expected to seek local tax breaks and other government-backed largess for the rest of the project’s massive build-out. And Arlington Heights’ mayor hasn’t ruled out helping.

That’s what has critics alarmed. They fear the suburb will cut a deal with the Bears that could stretch village finances and lead to higher taxes. “If I were advising Arlington Heights, I’d say stay away from it,” says Allen Sanderson, a sports economist and professor at the University of Chicago. “If Arlington Heights is competing against a Subway restaurant or some other mom-and-pop business, they’ll do OK. But negotiating against an NFL team, you’re likely going to lose.”

Already, the team — worth $5.8 billion, fifth highest valuation in the NFL — has hired the investment bank Goldman Sachs to explore its public finance options and open discussions with state and local officials. Part of the sales pitch: The venture will provide $9.4 billion in economic impact for the Chicago area, according to a study commissioned by the Bears. “We look forward to partnering with the various governmental bodies to secure additional funding and assistance,” Bears chairman George McCaskey and CEO Ted Phillips wrote in a September open letter, released a few days before they spoke to Arlington Heights residents at a local high school.

One possibility is for the suburb to create a tax increment financing district for part or all of the Bears’ complex. A TIF would freeze property taxes for 23 years. During that time, any incremental tax growth beyond that fixed amount would not go into the suburb’s coffers but would instead be plowed back into the TIF district’s roadways, utility upgrades, and other improvements. Since 1983, the village has minted five TIF districts, including one that spurred redevelopment downtown. “That’s a possibility we would consider even if it were a mixed-use development that didn’t have a stadium,” says Mayor Hayes.

That move would be a mistake, says Brian Costin, deputy state director for the Illinois chapter of Americans for Prosperity, a group that seeks to limit government involvement in the private sector and is backed by billionaire Charles Koch. Costin argues Arlington Heights is being too boosterish and should be skeptical of the Bears’ overture. “The village put itself at a disadvantage by already saying it’s willing to discuss subsidies — even before the Bears asked for anything specific,” asserts Costin, who adds that Arlington Heights should commission an independent feasibility study to determine how much the suburb would actually benefit from a pro football stadium.

Costin also offers this cautionary tale: south suburban Bridgeview’s construction of a 20,000-plus professional soccer arena, now called SeatGeek Stadium. In 2005, the town of about 16,000 issued around $130 million in bonds to finance the project, which subsequently ran into economic problems, leading to a decline in Bridgeview’s municipal bond ratings and higher property tax rates, according to news and financial reports. “Local government took on more than it could handle,” Costin says. And the Chicago Fire, the team Bridgeview built the stadium to host, moved back to Soldier Field after 14 years.

Hayes says his suburb is doing its own “due diligence” by talking to municipalities that already host NFL stadiums, including Arlington, Texas (home of the Dallas Cowboys); Foxborough, Massachusetts (New England Patriots); and Las Vegas (Raiders). The discussions focused on “each municipality’s experience, including planning, construction, and even current game day lessons to be learned,” Hayes says.

Moreover, the mayor is confident his municipal team has the savvy to hammer out a good deal. “We advised the Bears — and told the public — that it has to be ‘win-win’ for us as well.” The Bears are under contract to acquire the property for $197.2 million but have not officially closed the deal — and, of course, Chicago is still making last-ditch efforts to keep them in Soldier Field.

Meanwhile, Arlington International Racecourse’s era is coming to a slow but steady close. By year’s end, the track will be cleared out and left waiting for what comes next.