Officer Edward Poppish, Chicago Police Department, 11th District, and I’m here to oppose the release of Johnnie Veal.”

“Officer Olsen, Chicago Police Department, 10th District, here to oppose the parole of Johnnie Veal.”

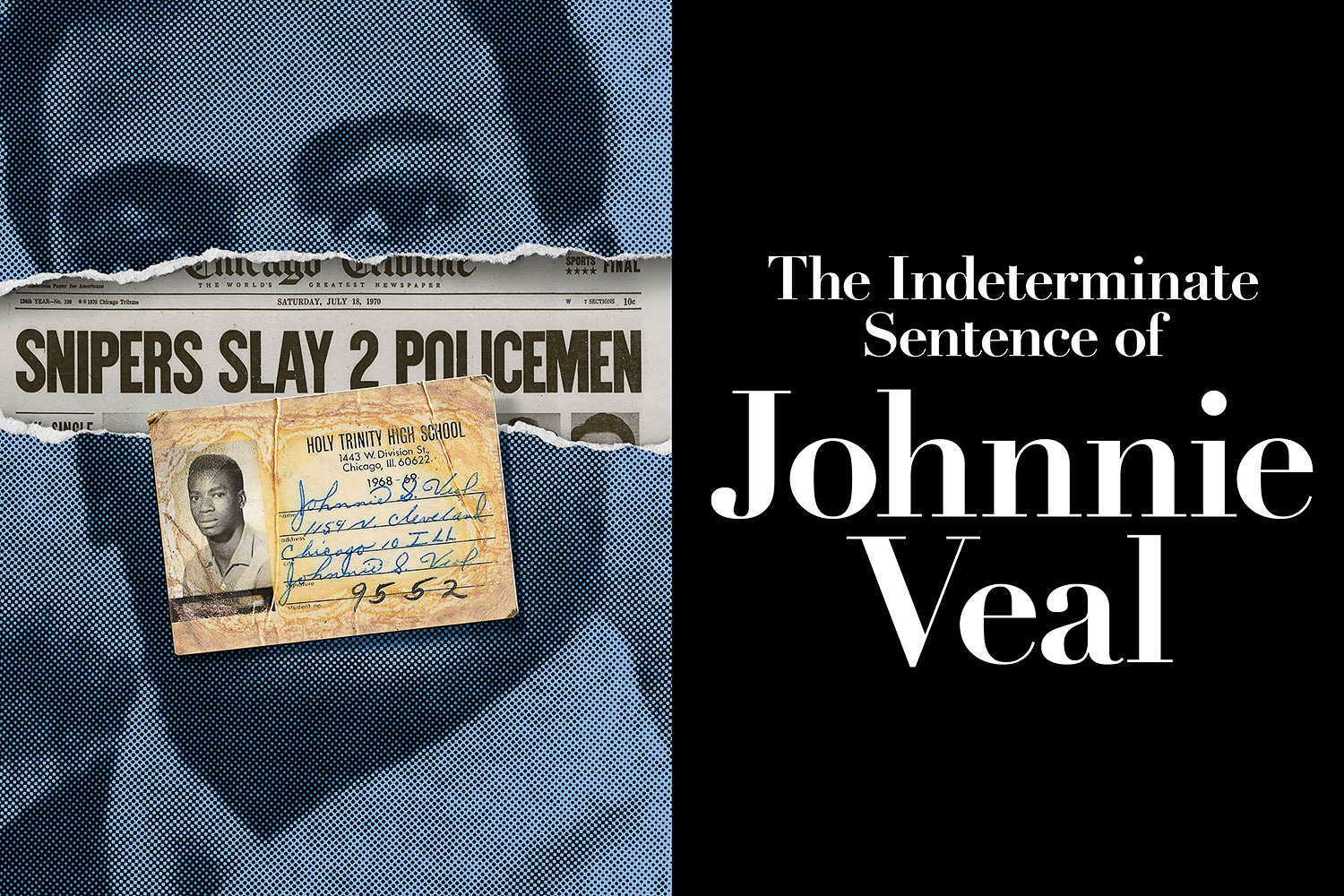

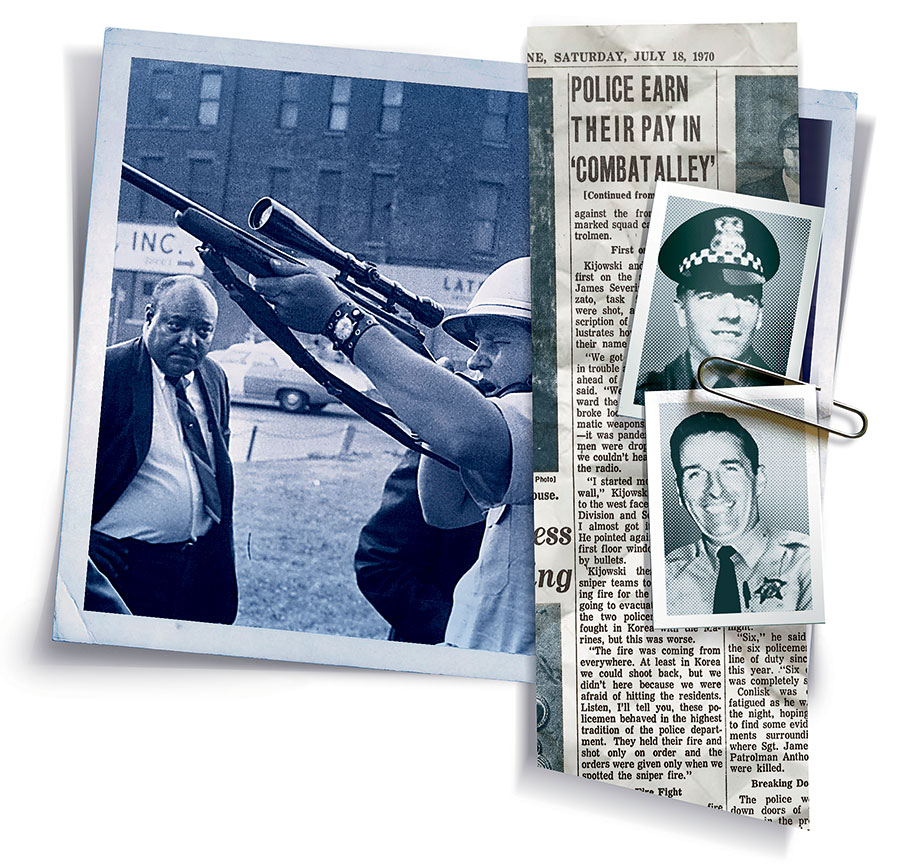

At the start of Johnnie Veal’s parole hearing in Springfield, the members of the Illinois Prisoner Review Board watched as some 25 police officers stood, one after another, to introduce themselves. In uniforms, service revolvers on their hips, a sea of blue.

“Officer Carlos Santiago, Chicago Police Department, here to oppose the release of Johnnie Veal.”

It was March 2018, just after 9 in the morning. The officers had bused down from Chicago, a three-hour drive. Few of them were alive in 1970 when the two policemen were gunned down at Cabrini-Green. But they’d heard about Sergeant James Severin and Officer Anthony Rizzato from older colleagues, on police message boards, or in news reports about the cop killer’s most recent bid for release. Some had seen the memorial to the two slain men inside the 18th District police station. But the lack of familiarity with the case was also the point of their presence. They were the embodiment of the police creed that a fallen officer is never forgotten. They needed to show the members of the parole board that there was no expiration date on honoring officers killed in the line of duty.

By the sleepy standards of the parole board, the crowd at the public hearing was enormous, and the proceedings had to be moved a few blocks from the board’s cramped offices to the Illinois State Library. Johnnie had secured a pro bono lawyer, a Chicago civil rights and criminal defense attorney named Sara Garber. She was there and introduced herself. As did a professor who taught Johnnie in a class at the prison, and several others who championed his release. But those in opposition to parole dwarfed the supporters. Along with the Chicago police officers, there were two state legislators, officials from the Fraternal Order of Police and the Chicago Police Memorial Foundation, veterans of the Chicago Police Department (“I was a survivor of the day that Johnnie Veal killed Severin and Rizzato”), and one of James Severin’s nieces — now, like Johnnie, in her 60s — who said her family had never missed a parole hearing in 35 years and would continue showing up generation after generation until both Johnnie and his codefendant died in prison.

Parole board members are like a jury without a judge, civilians appointed to decide whether a long prison sentence should or shouldn’t come to an end. The 12 members of the board present that morning were a motley group. Aurthur Mae Perkins, from Peoria, earned her GED at the age of 38, followed quickly by her bachelor’s and master’s, and became one of the longest-tenured principals in the city’s public schools — a street would be named in her honor. Pete Fisher, a former police chief in central Illinois, was one of four people on the board who’d worked in law enforcement. According to a report by the nonprofit media outlet Injustice Watch, Fisher had voted against parole 160 times, and for release only once, and that for a man whose maximum sentence was soon expiring no matter what.

By law, the parole board included roughly the same number of registered Republicans and Democrats, and the board was racially diverse as well. Kenneth Tupy, one of three former prosecutors on the board, had a bushy white goatee and was a member of the Knights of Columbus, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, and the Noon Lions Club. Virginia Martinez was from a mostly Mexican and Mexican American neighborhood in Chicago; in 1975, when she and a friend passed the bar, they became the first two licensed Latina attorneys in Illinois history. Board members came from all over a state that stretches from the Great Lakes nearly to Tennessee. Each time a former high school guidance counselor named Wayne Dunn opened his mouth, his drawl and twang were a lesson on just how much southern Illinois was the South. The governor appointed the members to six-year renewable terms, with the state Senate voting to confirm the appointments. In some states, serving on the parole board was a part-time job. It was full time in Illinois, and board members earned $89,443 a year.

Parole proceedings differ in each state as well as the federal system. Illinois, which restricts parole eligibility to a small portion of its prison population, stopped holding full hearings inside prisons in the early 1980s. Since then, only one board member goes into the prison to interview a parole applicant. That person then reports back to the rest of the board during a monthly public hearing in Springfield, sharing firsthand impressions of the petitioner and a recommendation on parole suitability. The board member who interviewed Johnnie this time was a former prosecutor and Republican state legislator named Tom Johnson.

When they’d met at the prison a few weeks earlier, Johnnie described to Johnson a curriculum he was developing with a nearby college. It was for people like him who were growing old behind bars and who’d missed the lives, and deaths, of many of their loved ones on the outside. Johnnie said longtimers needed a forum to work through their grief and shame. They needed help to keep from going on a rampage or giving up. “How do you do a bit when you’re traumatized, raped, beat down, when you lose your mother and sister, when you’re under stress of the Department of Corrections?”

Johnnie called the initiative Project Sound Off. “People expressing themselves, or sounding off, on all the things that affect your life just sitting in a cell,” he said. For those serving long prison terms, the lucky among them might leave prison at the age of 50 or 60 or 70. Sound Off was intended to prepare them for the distinct challenges of reentry in older age. But the rest of them had to face the grim reality that they’d likely die behind the prison walls. Johnnie tried to convince men at the prison — as well as himself — that a slow death in a cell didn’t mean their lives lacked meaning and dignity. “The life I lived inside has value,” Johnnie would say. In Sound Off, they put together their own legacies, something they could pass on. They assembled picture albums and packets of their certificates and academic achievements. They composed short autobiographies, commemorating major events and milestones in their lives that might otherwise go unnoted. They prepared their last wills and testaments. They indicated where they wanted their belongings sent, and what they wanted done with their bodies.

Johnnie went before the parole board for the first time in 1980. In 2018, Johnnie needed the support of seven of the 12 members, a majority, to leave prison. In his 18 previous parole attempts, he’d never received a single vote in favor of his release. Not one. Garber joked with Johnnie that his chances might improve if he looked less muscular and spry at 65. His neat goatee was speckled with gray, his middle had thickened, but Johnnie still played doubleheaders in the prison’s softball league against men a third his age.

At the parole hearing in Springfield, Johnson related his findings to his colleagues. “Mr. Veal appeared to be in good health, was fully engaged, and very articulate,” he said. Johnson was charged with retelling the story of Johnnie’s crime, an account based on the statement of facts that police and prosecutors assembled for trial. “These two men, the evidence showed, were lying in wait with .30–30 rifles to assassinate the walk-and-talk officers.” Johnson said the murders were “an outrage against society.” The other board members listened intently, jotting notes or checking documents. They’d have an opportunity to ask questions and deliberate before voting for or against parole.

Johnnie tried to convince men at the prison — as well as himself — that a slow death in a cell didn’t mean their lives lacked meaning and dignity. “The life I lived inside has value,” Johnnie would say.

Johnson went on to enumerate Johnnie’s many accomplishments. In prison, he’d earned 25 certificates — as a paralegal, in computer coding, in business management. He was accredited as a tutor. He was a skilled flutist and guitarist, and he recently defended a female staff member from another incarcerated man, a guy in his 30s who, a report noted, broke Johnnie’s jaw. Johnnie believed people were fundamentally good, that “it’s their experiences, a trigger, that makes them turn left rather than go right.” He’d shrug off this fight as part of life: “He advanced toward her, and I stepped between them … and, you know, I did what I had to do, and it wasn’t no big deal, a scuffle’s a scuffle.”

Johnson recognized that Johnnie had achieved what he had in prison despite the dangers and uncertainties, the lack of programming, the unhealthy food, the inadequate medical care, the isolation, and the repeated parole rejections. “In my interview with Mr. Veal and my review of the entire record here,” the board member said, “Mr. Veal is certainly a very, very different person today than he was at age 17.”

Johnnie’s transformation, while dramatic, was not uncommon. The age distribution for crime is something that criminologists across the political spectrum agree on as fact. The Bureau of Justice Statistics and countless studies show that arrest rates for violent and nonviolent offenses peak when people are in their late teens and early 20s. From there, criminal behavior drops steadily. Nine in 10 homicides are committed by those under 35. Among the prison population as a whole, about a third of the people who leave are arrested again within the first six months of their release, and within three years around 40 percent are returned to prison. But the arrest rate for anyone over 50 is small, less than 2 percent. And for people Johnnie’s age, 65 or older, it is near zero.

The truth is that the United States could let out nearly everyone in prison over 55 and see very little statistical change in crime. Yet the country is doing the exact opposite. The number of older people in state and federal prisons is increasing faster than any other age group. How can anyone claim that the point of incarceration is to incapacitate the truly dangerous when there are more people older than 55 in U.S. prisons (165,000) than there are people in the high-crime range of 18 to 24? Many of these older prisoners were convicted of violent crimes when they were young, and they are now serving extremely long sentences or life without parole. Geriatric health care in prison is both disgraceful and expensive. It costs, on average, three times more to incarcerate an older person than a younger one.

With over two dozen uniformed police officers and the relatives of the murdered cops staring at him, Johnson admitted that he was struggling with his vote. He had on the one hand the assassination of two police officers in 1970, and on the other the extent to which Johnnie had changed during his half century of incarceration. He wasn’t sure whether the scales had tipped toward mercy.

In Illinois, the parole board is guided in part by the state constitution, which affirms that the purpose of incarceration is “restoring the offender to useful citizenship.” The board, therefore, is in the business of corrections. State law also instructs board members to deny parole to anyone who still appears to be a danger and unable to abide by the lawful conditions of his or her release. They should vote against a candidate’s freedom as well, the law says, if “release at that time would deprecate the seriousness of his or her offense or promote disrespect for the law.” Most states use variations of the same language. But it is a paradoxical loophole. Crimes don’t become less serious over time. A murder remains a murder, and an offense by its very definition always disrespects the law.

Johnson then mused aloud whether it was time to parole Johnnie. He said, “If somebody is going to serve that 47 or 50 years, I believe that the public would certainly understand that that’s a lifetime for most people.”

Johnson, who was seven years older than Johnnie, would be dead in nine months, from cancer. His obituary in the Chicago Tribune, in December 2018, began by noting how he had “evolved from an assistant county prosecutor to a backer of what’s now known as criminal justice reform, frequently questioning the moral and monetary costs of imprisonment while advocating rehabilitation over incarceration.” In 2011, he was one of four Republicans in the state Senate to vote with Democrats to abolish the death penalty in Illinois.

At the parole hearing in 2018, he pointed out that Johnnie was convicted on the theory of accountability, for planning and assisting with the crime, not for pulling the trigger. “He was 17. At the time, he had a ninth-grade education, was involved with gangs. He’s remorseful to the extent of understanding the grief that was caused by the incident.” Johnson said Johnnie was not a danger to others. By any actuarial measure, and based on his conduct over the past 20 years, Johnnie posed no threat to reoffend.

“Would it bring disrespect to the law?” Johnson questioned. “I struggle with that. Everybody can have different views with that.”

Garber, sitting in the audience, wondered for the first time if Johnnie might have a shot at making parole.

Johnnie was not at his parole hearing that morning. He was at Hill Correctional Center, about a hundred miles away in western Illinois. He wasn’t nervous. Johnnie didn’t get nervous. But he hated feeling powerless as his future was being decided. He could do nothing to affect the outcome. “I’m not in a position to drive,” as he put it.

Parole board member Tom Johnson was struggling with his vote. He had on the one hand the assassination of two police officers, and on the other the extent to which Johnnie had changed during his half century of incarceration.

Johnnie dealt with these concerns, as he did with most things, by staying in constant motion. He taught a morning health class to other guys at the prison on hepatitis and HIV. He worked a shift in the laundry. When he first met Sara Garber at Hill a few months earlier, in the tiny room reserved for attorney visits, he flooded her with documents, his bounty of degrees and certificates. Before she even sat down, he was passing her the legal briefs he’d composed in his cell on an ancient Brother typewriter. He explained to Garber that he mentored, tutored, organized activities. “My accomplishments are greater than the average man’s,” Johnnie would say. He hoped there was a chance this year that the parole board might judge him on his time served and rehabilitation. “They made me the supervillain. I’m not Dracula. I’m not the boogeyman.” But the morning of his parole hearing, he refused to dwell on any of that.

When Johnnie first entered prison, in 1972, he was 19 and had spent the previous 18 months leading up to his conviction in the Cook County Jail. He was, according to his processing papers, 5-foot-10 and 161 pounds. The uniform he’d been issued hung loosely on his teenage frame. He was in a maximum-security prison called Stateville, and Johnnie found himself staring up at a galaxy of cages. The cells were stacked five stories high; each tier stretched longer than a city block. The cages were also at that moment all open. Roaming about in the adult prison were grown men. A number of them now circled Johnnie and the other new arrivals, looking them over as if shopping for items they’d be back to purchase later. “Fresh fish!” men whooped.

Johnnie once saw a documentary about a sardine run. Sardines spawned in the cool waters off Africa and then migrated in enormous shoals that darkened the ocean with their numbers. The sardines, on their journey, were an invitation to predators. The tiny fish were set upon by sharks and humpback whales, by dolphins and seals, by game fish and dive-bombing birds. The feeding frenzy created its own violent churn. In Stateville, Johnnie feared he was the sardine.

Johnnie and the other newbies were still being window-shopped when a commotion drew everyone’s attention to an upper tier. Two men in their prison blues were fighting. A guard rushed over to break it up. The fighters turned on the officer. Johnnie watched as the inmates tried to wrestle the guard over the railing to drop him five stories to his death. Other guards raced up the stairwells waving clubs and hollering. Suddenly Johnnie’s throat clenched as he breathed in fire. He’d swallowed the pungent Mace that was filling the cellblock. An officer hovering overhead on a catwalk locked and loaded a rifle. Johnnie felt in his spine the echo of the metal engaging, the clicking and cocking. Then the thunder of a warning shot filled the cell house. Johnnie dropped like a stone.

That was day one. Johnnie thought, even at 19, that he’d seen everything growing up in Chicago public housing. In the weeks that followed, he witnessed brutality with a casualness and regularity that shocked him: Walking to the workshops, a man stabbed. On the yard, the weight bar used to crush the windpipe of a guy on the bench press. A man struck in the head with a metal pipe and reaching instinctively to hold in his brain matter. There was some version of prison that existed on paper in which Johnnie was supposed to use his punishment to reflect and reform. He was in a “correctional facility,” after all. But rather than being reformatories, American prisons are criminogenic: They cause criminal behavior. Johnnie had more imminent concerns than building a résumé to present at a parole hearing in 10 years. He focused narrowly on the choices he faced in prison, which as he saw them then were really only two — survival or annihilation.

Johnnie survived. He’d received hundreds of disciplinary tickets during his first decades of incarceration. He spent years in segregation. But in 2018, his petition to the parole board exhibited how much he’d transformed. “He have advised me to get my GED and give up some of my bad habits and make a 180° for the good,” a man locked up at Hill with Johnnie wrote in one of many glowing testimonials. Another, from a young man who was being preyed upon sexually by a fellow inmate: “I felt it wasn’t no one else I could have turned to. As my mentor Mr. Veal had took on my problems as his own and went to go talk with this individual.” That individual, it turned out, didn’t appreciate the talking-to. Later that night, during chow, the guy charged into Johnnie’s cell, attacking him. For defending himself, against a man 20 years his junior, Johnnie earned a disciplinary ticket — it was one of only three violations in the nine years prior to the 2018 hearing.

Garber wanted to emphasize to the board that this ticket, rather than being a mark on Johnnie’s record, revealed the exceptional content of his character. He risked his own well-being to protect the vulnerable. Johnnie downplayed it to her, though. A lifetime behind bars had taught him to be cagey. Once something was said out loud in prison, you no longer controlled it, the words could travel and be used against you. Whenever Johnnie was pressed to speak about himself, his default was to deflect, to explicate impersonally, to analogize as if teaching from some jailhouse The Art of War. “How can I say this?” he said of the different ways he’d plotted to foil prison rapists. “I got cattle on my ranch. If your cattle get mixed up with my cattle, they still my cattle. If I take them by force, now I got to fight you and everyone else on the ranch. I’m risking the chance of an ongoing battle. That’s all it is — gauge your wars. Fight the good fight.”

Around lunchtime, when the parole hearing in Springfield had certainly ended but Johnnie had yet to get word, he went to play music. His band, Concrete and Steel, got practice time once a week, and he wasn’t going to miss it to sit in his cell and stare at the wall. Before prison, Johnnie hadn’t touched an instrument, but he took a class inside with a jazz trumpeter who came in as a volunteer. The musician started Johnnie and the other men on an African thumb piano, a kalimba. He showed them an 18-stringed sitar, and what seemed like every other instrument known to humanity. Johnnie got good on the saxophone and flute. He was a natural. Things came easily to him. As a boy, he ran track competitively, mastered karate, tae kwon do, Ping-Pong, and really everything he picked up. His current prison didn’t allow wind instruments, supposedly for health reasons, so Johnnie played the guitar and bass. He worked with the program officer at Hill to organize concerts for Christmas and Black History Month.

The force of Johnnie’s determination drew people into his orbit. He had a glinty stare that remained imposing even as he smiled. His silences seemed charged with planning. He was not a follower, and he moved through the prison hunch-shouldered with the single-minded purpose of a boulder. Each year at Hill, Johnnie helped pull together a battle of the bands. He played for the prison population at graduations and holidays. Garber shared with the parole board a letter of appreciation given to Johnnie by the warden: “Thank you for everything you do as an inmate mentor. You have single-handedly helped to change the mindset, attitude, and lives of other offenders.”

The summer Johnnie was 16, in 1969, he traveled with his family to the farm in Mississippi where his mother grew up. His girlfriend, Leora, came along, and so did their newborn, a girl they named Lawanda. Their home on Chicago’s Near North Side, Cabrini-Green, was a massive public housing development, with upward of 15,000 mostly Black people balled together in a fist of 23 towers. The entire complex, 3,600 homes, covered fewer than five city blocks in each direction, a mere 70 acres. The property in Mississippi wasn’t that much smaller, and it was for only their one family. The land contained 40 or 50 peach trees, fields of blackberries, butter beans, and peas. The city kids picked the crops as if for sport. Holding her granddaughter that summer, Johnnie’s mother announced that the girl’s fair skin was the same color as the peaches, and from then on that’s what everyone called her. Peaches.

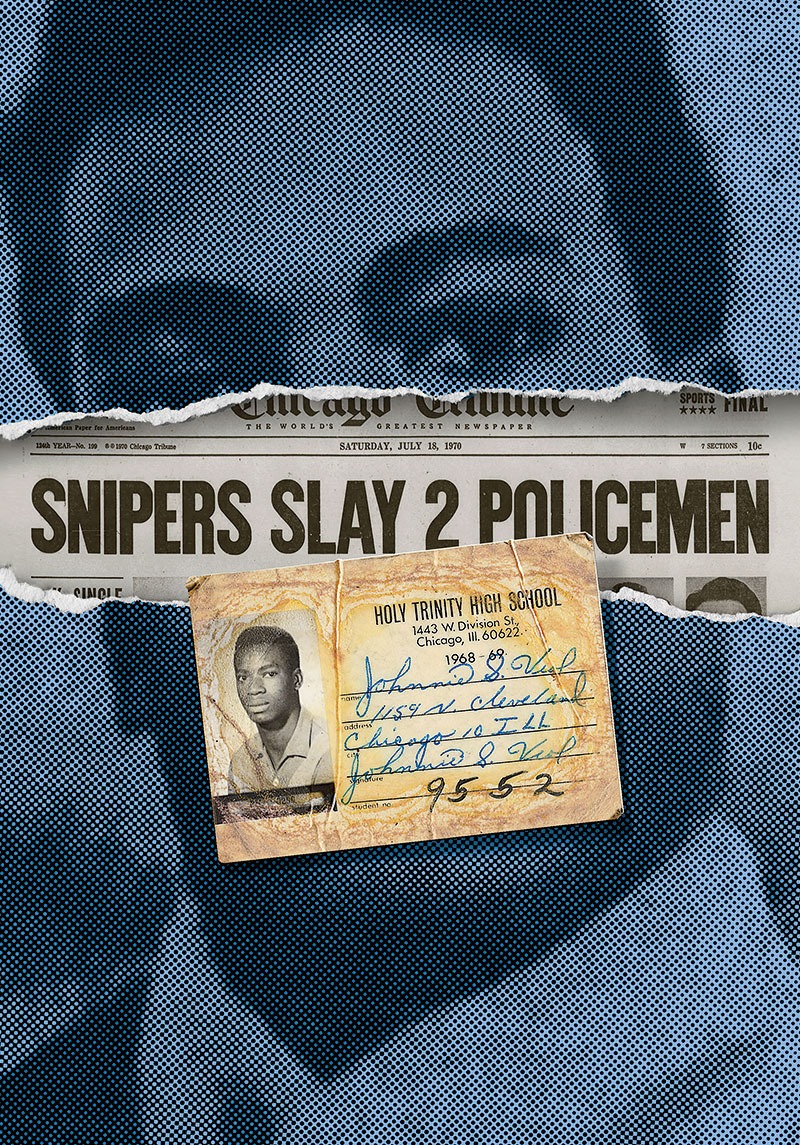

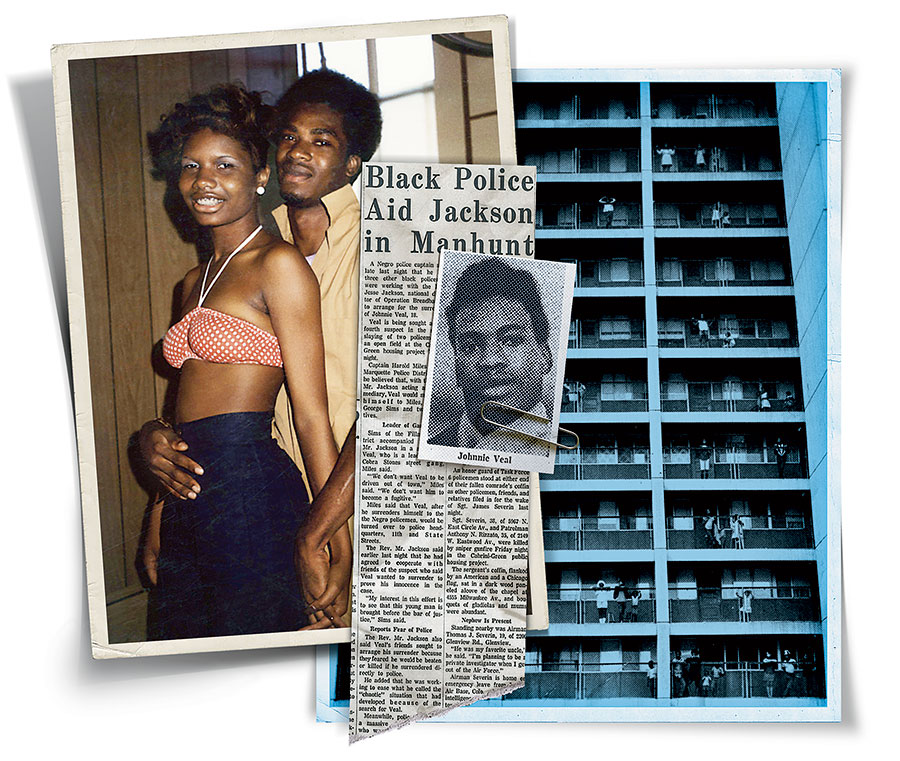

Johnnie caught his case the summer after that Mississippi trip. On July 17, 1970, a Chicago police sergeant named James Severin went to check out a report of gunfire coming from one of the Cabrini-Green high-rises. Severin was 38, a 13-year veteran of the force. He had worked the security detail protecting Martin Luther King Jr. in 1966, when the civil rights leader turned his attention from voter suppression in the South to racist real estate practices in the North. King had found more than enough to protest in Chicago. Residents of Cicero responded to marchers with shouts of “White power,” Nazi flags, bricks, and bottles. Severin now led a goodwill community-relations unit of eight officers at Cabrini-Green. They walked the neighborhood and tried to make themselves available to the people who lived in the housing development.

It was 7 at night that July, an hour before the end of Severin’s shift, and he took one of his patrolmen with him to investigate the shots fired. Officer Anthony Rizzato had joined the Chicago Police Department four years earlier, signing up along with his twin brother. Severin and Rizzato entered a park surrounded by towers. They crossed a baseball diamond. A woman in front of one of the buildings waved to Severin, and he waved back.

At the crack of the first rifle shot, Severin clutched his chest. A hole appeared there, the size of a baseball. He toppled forward. Rizzato, 10 feet behind him, turned to help, or maybe tried to run for cover. He didn’t get far. Another shot spun the younger officer around, a complete about-face. He took two or three more steps and then fell. The coroner who examined the bodies that night reported that each man’s service revolver remained holstered. “They didn’t know what hit them,” he said.

Johnnie was 17 that summer. Along with other teenagers in his high-rise, he had joined the Cobra Stones, an affiliate of the Black P. Stone Nation, then Chicago’s most powerful Black gang. He and another Cabrini-Green resident, 23-year-old George Knights, who was known by his middle name, Clifford, were charged with the ambush and execution. “Can you conceive of a worse, a more heinous crime?” a prosecutor asked at trial, underscoring the point that the slain policemen were there to help the community. “We talk about retribution. It’s a high-sounding word for punishment, to fit the crime. You do an act, you deserve a punishment. Your child goes into the sugar jar, you slap her hand. You kill a couple of innocent human beings, you deserve what our law, the law of Illinois, says is a proper punishment, and that happens to be death.” Johnnie and his codefendant escaped lethal injection, but barely. They were each sentenced to indeterminate prison terms of 100 to 199 years.

Throughout Johnnie’s trial and decades of incarceration, he maintained that his was a case that caught him. He insisted that he didn’t shoot the two officers. He didn’t deny being in the Cobra Stones, nor firing guns across a narrow strip of blacktop at other boys from Cabrini-Green who fired back at him. The kids in the high-rises facing Johnnie’s had joined gangs of their own. Johnnie had played games against them growing up; he could pick them out of a crowd by their batting stances or their gait as they sprinted to catch a football. By their late teens, however, these boys were attempting to kill one another nearly every day. “We were ghetto thugs trying to survive, fighting other ghetto kids,” Johnnie would say. Yet he insisted he had nothing to do with the murders of Severin and Rizzato. “The police weren’t even on my radar.”

As Johnnie waited for his lawyer to call with news from Springfield, he took advantage of an opportunity to venture from his cell, to “play on the streets,” as he called it. He made his way to a bank of phones and dialed Darlene Holmes. Johnnie found a way to call her three times a day — before she left for work in the morning, during her lunch break, and before she went to bed at night. He bartered for other people’s phone time when he exhausted his own. Darlene had also grown up in Cabrini-Green, in a neighboring high-rise, and she and Johnnie had been sweethearts as children back in the 1960s. She’d married a Cook County sheriff’s deputy and raised a family. After her husband died, she moved to a small city in western Kansas, where she worked as a fitness specialist for cancer patients. She and Johnnie never fell out of touch. They wrote letters and phoned.

Around the time they turned 60, in the early 2010s, they decided to get serious. They weren’t getting any younger, Johnnie teased. She started to take the train in from Kansas, using her vacation time so she could stay an entire week. They’d sit in the visiting room and talk for hours. Darlene was a health nut, but Johnnie’s vice was junk food, and he’d devour candy bars from the vending machines as they laughed about the past. They were permitted to hold hands and even kiss. On the day of Johnnie’s hearing, they talked on the phone about the life they would lead if he somehow made parole. She was thinking about retiring from her job, and they used their minutes to imagine whether they’d live in Kansas or move elsewhere. “I’m an Illinois boy,” Johnnie said. They joked about how boring their days together would be — she liked to go to bed early; he might sneak out for ice cream — and how that’s what made it so appealing.

Illinois abolished parole in 1978 — one of 16 states, along with the federal government, that have scrapped it. Anyone convicted of a felony in Illinois and sent to prison after that date cannot be released by a parole board. There are roughly 30,000 people in prisons in this state today. Johnnie was among fewer than a hundred who predated the law change and were grandfathered into the old system; they still come up for parole. Everyone else? They have to serve out their entire term, or a mandatory percentage of it. Some can still earn “good time” reductions.

When Johnnie entered prison in the early 1970s, the United States incarcerated a total of 200,000 people. In 2023, that number seems quaint. The country locks up well more than a million people. In federal and state prisons today, there are more than 200,000 people alone serving life without parole or sentences so long that they amount to the same thing. Many states, including Illinois, are now debating whether to reinstate parole and expand eligibility — whether they need this critical release valve. Doing so would mean giving hundreds of thousands of people in prison serving long sentences a shot at being returned to useful citizenship.

Parole hearings are subjective and riddled with inequities. They also wrestle with the most profound questions underlying the country’s values around crime and its consequences. What must someone convicted of a serious crime do to get a second chance? What is a prison term even supposed to accomplish? Parole presupposes that change — a correction — is possible. By exploring the parole process, we can see how the United States created the crisis of mass incarceration, and how we might find a way out.

At Johnnie’s hearing in Springfield, the chairman of the parole board interrupted Tom Johnson at one point, with polite formality. “If I may,” he said. Craig Findley was 70, with cottony white hair, a cottony voice, and a boyish face. He’d served on the Illinois parole board since 2001, longer than any of his peers. He was a former state legislator and the son of an 11-term U.S. congressman. The father and son both practiced a moderate Republican politics that, by the midpoint of Donald Trump’s presidency, seemed as obsolete as rotary phones and video rental stores. “Politics ends with the water’s edge, and we’re one country, one people, and we have to find common cause,” Findley would say.

He lived in Jacksonville, a small city in central Illinois named after Andrew Jackson, and he served on the chamber of commerce and the board of the public library and played trombone in the city’s symphony orchestra. During his time in the state legislature, Findley viewed himself as a “law-and-order” guy. He summed up his beliefs from that time: “People commit crime, there’s a price to pay.” He supported the sort of tough-on-crime sentencing laws that would contribute to incarceration in the United States going mass. In Illinois, the prison population went from 5,600 people at the start of the 1970s to nearly 50,000 by the 2010s. Black people made up less than 15 percent of Illinois residents, yet Illinois was one of 12 states in the country in which more than half the people in prison were Black.

When Findley joined the parole board, though, he started to meet people in prison serving long sentences, and his ideas changed. He’d say, “I saw humanity in them that I wouldn’t have known had I not taken on this job.” He’d say, “It’s hard to understand how incarcerating a person past the age in which we think there’s no likelihood of the criminal committing the same crime is of value to society.”

At hearings, Findley administered the proceedings like an attentive host, explaining rules and procedures and ensuring that everyone felt duly respected. After heated exchanges between board members, he tended to validate each of the conflicting viewpoints. He’d say, “We’re all informed by our own experiences,” or “Both sides were very capably represented today,” or “I think we’re at the point that we’re not going to persuade someone else how to vote. We have to decide for ourselves what is the proper thing to do.” He’d instruct them to vote their conscience. At one hearing, Findley expounded on the value of parole. He told his colleagues, “The trial court could never know what became of this 19-year-old murderer. That is for the board to consider.”

At Johnnie’s hearing, Findley said that it had been his job to listen to the victim protests at a separate session not open to the public. “It was grueling,” he said. “All of the family members of the two slain officers spoke passionately that they’ve not been able to overcome the grief of their loss.” He explained to everyone in attendance that the law in Illinois gives victims or their survivors a right to be heard at parole proceedings. The board was obliged to factor in their suffering when considering the suitability of ending a punishment. He said he took scrupulous notes during the protests, and he began to check them to ensure he didn’t miss anything. He believed a total of 14 members of the Severin and Rizzato families testified. “Each talked as though the crime occurred yesterday.”

Findley could have discussed the victim testimony with the other board members in an executive session closed off to visitors, as was often done. But in this high-profile case, with more than two dozen police officers present, he chose to share what it was like to wrestle with the history and ramifications and politics involved in some of these crimes. He read from a letter submitted by a police officer who worked at Cabrini-Green in the 1980s: “I feared ambush, beatings in the stairwells and shootings, rock throwing, and falling debris. I prayed that God and the good police would look after me.” Johnnie last set foot in Cabrini-Green in 1970, seven years before this officer started on the job, but Findley said the words still provided a picture of what Chicago public housing projects were like. “They were horrible places,” but inhabited, he said, “by some good people.” The parole board chairman added that Chicago’s police superintendent, Eddie Johnson, had grown up in Cabrini-Green around the same time Johnnie lived there, moving away when he was still a child. He had also testified at the protest hearing. “When [Johnson] was a young boy,” Findley related, “Johnnie Veal burned his older brother with a flare.”

Findley, as board chairman, voted last. As a personal rule, he rarely expressed an opinion that indicated ahead of time whether he was for or against parole. He didn’t want to influence the outcome. But now, in his own courteous way, Findley was saying he felt strongly enough to tip his hand. Tom Johnson, who had sounded lenient, would get to speak again and present his recommendation. Findley, though, believed it necessary to impose a different point of view. He talked about a murder of another Chicago police officer a month before Johnnie’s hearing. Commander Paul Bauer was downtown, in February 2018, for meetings with city officials when he chased a fleeing suspect. He caught up with the man, and the two struggled, tumbling down a flight of stairs. The suspect shot Bauer in the head, chest, and neck. Findley recognized that equating the two crimes against police officers, a half century apart, was problematic. But, he insisted, it was also unavoidable. “While Mr. Bauer’s death has nothing at all to do with the case before us of Mr. Veal, it was very much in the words and, I think, the thoughts of those who testified against him,” Findley said.

Bauer’s murder had also deeply affected Findley. Although the last Cabrini-Green tower was demolished in 2011, Bauer had been commander in the same district where Severin and Rizzato served; Bauer was in charge of the Cabrini-Green neighborhood 50 years later. Findley underscored the connection, saying Bauer was doing the same work to bring order and peace to the area.

If a parole hearing were more like a trial, then this would have been when Johnnie’s lawyer objected, on the grounds of relevance. A judge would have likely ordered that any reference to Commander Bauer be stricken from the record. None of that happened, of course. At Johnnie’s protest hearing, the director of the Chicago Police Memorial Foundation testified that Johnnie should remain in prison “so we can be a little safer and honor Paul Bauer.”

Findley had been quoted in the Sun-Times saying neither Johnnie nor his codefendant would ever get out of prison. At the start of Johnnie’s hearing, he apologized, calling his remark “intemperate” and “potentially prejudicial.” It was totally unlike him to speak out of turn like that, and he wished he hadn’t said it. “Frankly, I could not know whether Mr. Veal will be paroled today or in the future. It’s impossible to know.”

All he knew was that today, he would cast his own vote against Johnnie’s parole. “I’ve voted to parole more long-serving inmates than anybody on this board,” he said. He believed in second chances and rehabilitation. He believed there was a reason that prisons were called correctional facilities. “But there are some cases that I just can’t overcome. And this is one of them. I can’t support Mr. Veal. Please take the roll.”

Garber reached Johnnie by phone not long after his hearing. She shared the bad news first: The board again rejected his parole application. The vote, in fact, was unanimous, 12 to 0. Even Tom Johnson in the end couldn’t get past Johnnie’s assertion of innocence, saying Johnnie still took no responsibility for the murders. Garber was a fast-talker, plowing ahead as if punctuation marks didn’t exist, and she narrated the day’s events at a breathless clip. She described the police who filled the chamber. “It was so fucked up,” she shouted. She explained how Findley brought up the recent murder of Bauer and the protest testimony of the Chicago police superintendent.

“A flare?” Johnnie repeated. He couldn’t believe that in 2018 they were trying to say he burned the police chief’s brother in the 1960s. “I never saw a flare in the neighborhood,” he said.

Garber told Johnnie she had some good news, too. She said the parole board took the question of his rehabilitation seriously. They weren’t blinded by the crime. For the first time in four decades, the board acknowledged the fact that he was convicted for plotting the murders, not as a shooter. The board members still believed Johnnie guilty. That he was responsible, in some way, for the murders of two police officers. But Garber insisted the day was also a success. They got some traction with the board. They moved the needle.

Which meant Garber believed Johnnie had a chance of winning his freedom at his next parole hearing. A fact recognized at a prior hearing could be ignored at the next; board members were not bound legally by precedent as in court cases. But Garber still felt they had something to build on. Johnnie wasn’t due to appear before the board again until the end of 2020. But they needed that time to prepare. They had a lot to do in the upcoming two-plus years. Garber had plans to recruit law students to comb through Johnnie’s trial transcripts. She wanted to track down any surviving witnesses of the police shooting in 1970. She would request redacted police reports, publicize the case, and reach out to Johnnie’s codefendant, getting him a lawyer in the process. His next hearing would be his 20th. Johnnie would have spent 50 years in prison. Huge, round numbers. Garber felt that had to count for something in a justice system that saw time as its measure of punishment.

Johnnie listened to his lawyer in silence. It didn’t take long for his pragmatism to kick in. The gears of his mind started to turn, the teeth catching. He saw what Garber saw. The parole board had never before recognized that he was convicted on accountability, that even the courts said he wasn’t the shooter. That was a big deal. And Johnnie was motivated by the way Garber laid out a battle plan. He was competitive, and this was a political fight. Garber had worked on Johnnie’s case for less than six months; he started to imagine what they could do together over the next three years. He said he had to reinvent himself again, change directions. He couldn’t do the same thing at the next hearing and expect a different result. That was the definition of crazy. He wasn’t the same person at 65 as he was at 62 or 59, and he’d be different three years from then. He had to show them that he was continually growing as a person. That the years mattered.

When Tom Johnson came to Hill to interview Johnnie, the two of them had connected. The parole board member was eager to learn more about Johnnie’s accomplishments, and Johnnie felt seen. But as they ended their conversation, Johnson said something that stuck with Johnnie. He offered what was meant as a lighthearted compliment. “We might need you more in prison than we need you out.”