On the third floor of the Field Museum, down a long hallway lined with large vintage bas-relief maps, a sign hangs on the door of paleontologist Jingmai O’Connor’s office: “Archaeopteryx is the most important fossil of all time. CHANGE MY MIND.” Now, thanks to the efforts of the Field, Chicagoans will get to see one up close: In May, the museum unveiled the acquisition of its very own such rare fossil, one that is particularly extraordinary.

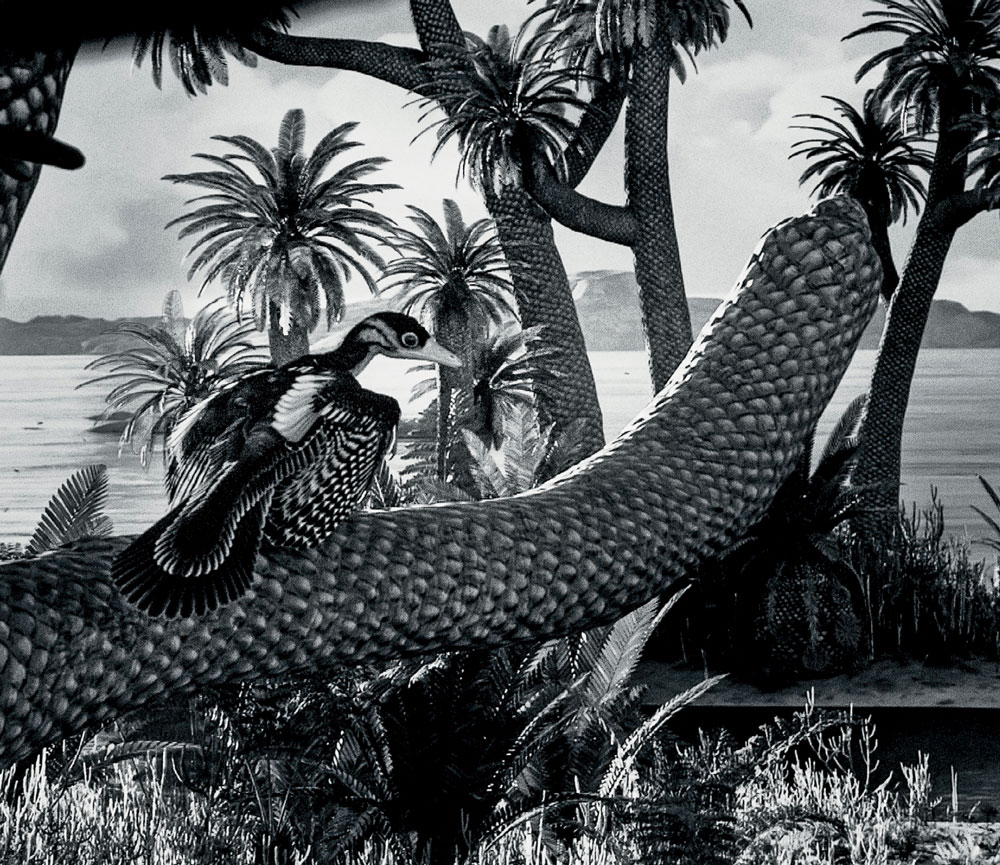

Covered in feathers and with a beak full of teeth, archaeopteryx has been an icon of evolution since the first fossil of its kind was discovered in Germany in 1861. The genus, which is the earliest known dinosaur that is also a bird, indisputably linked the two groups.

Like the 12 previously known examples — a few complete, the rest just partial — the Chicago Archaeopteryx was unearthed in Bavaria. It was encased in its large slab of Solnhofen limestone, so no one knew if it was still intact. Shortly before the museum made the seven-digit purchase in 2022, O’Connor got a call from the Field’s president: “Are you sure we should do this?” he asked. She responded affirmatively: “We can see the wings, which are the most important part.”

The fossil arrived under a spy-worthy veil of secrecy, referred to by the code name Crushed Bird. O’Connor and her team immediately X-rayed it, revealing that the Field had won the paleontology jackpot: It had acquired the world’s best-preserved archaeopteryx. Then began the meticulous process to carefully remove layers of rock from the 150-million-year-old fossil — it lived around 80 million years before most of the dinosaurs went extinct — clearing the way for O’Connor to conduct yet-to-be-published research. “I don’t want to go into detail about what the feet actually tell us yet,” she says, “but we can use these soft tissues, never seen before in any archaeopteryx, to confirm ecological predictions about this animal.”

The pigeon-size Jurassic bird now lives permanently in its own special section within the Griffin Halls of Evolving Planet, also home to its famous distant cousin, Sue the T. rex. While the Field’s top brass call it the most important acquisition since Sue, O’Connor goes one step further (hence the sign on her door). “It’s going to have a real impact on our standing in the research community,” she says.