|

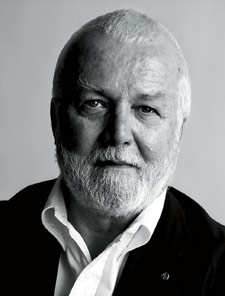

Russell Banks has been lauded for his bleak, realistic narratives of working-class life: Think Continental Drift, a book about a desperate Haitian immigrant and a white, working-class charter boat captain, which was nominated for a Pulitzer in 1986. His latest novel, The Reserve, takes a different tone: Kicking off in 1936, it engulfs the reader in a tale of passion, murder, adultery, and social hierarchy—with offshoots into art, lobotomies, the Hindenburg, and leftie politics. The Adirondack Mountains, which the 67-year-old Banks calls home, even add an atmospheric layer to this history-tinged saga. Victoria Lautman interviewed Russell Banks, who spoke by phone from his home in Saratoga Springs.

|

Q: Your publisher describes this story as a departure for you.

A: Well, there are four main characters, and three are from what we’d call the upper class. I haven’t really focused much attention there before, within the glamorous world of Manhattan society. In a way, it’s more romantic….

Q: They’re saying it’s also less dark than your others.

A: I don’t think anyone’s going to make a musical out of it. It doesn’t exactly end happily for anybody. But it’s not really a depressing book, and was certainly fun to write, and to visit that world for a couple of years.

Q: Jordan Groves, the artist/adulterer/aviator/socialist at the book’s center, was inspired by American artist Rockwell Kent. Why are you so drawn to him?

A: He lived in the Adirondack region for most of his career, although he didn’t fly a plane. But he—along with other intellectuals and artists of the era—like many today, found himself identifying with a class of people who really weren’t part of his social, economic, or political life at all. He was caught in a moral conundrum since he made a lot of money, had a certain clientele and social life, then became socially identified with the very class that his politics attacked.

Q: Hmmm. Considering your own working-class roots, you must identify with the guy.

A: Yeah, it’s something I’ve thought about my whole life. You end up with a really divided character, and I don’t think that’s peculiar to me. You saw it so much in the 1930s, with Dos Passos, Hemingway, Rockwell Kent. Look, Doctorow lives out there in the glamorous Hamptons, but he isn’t exactly a member of that society.

Q: You’ve said that writing saved your life. When did you actually realize that?

A: Probably by the time I was in my mid-20s. I was married, in New Hampshire, working as a plumber and writing at night, and my life had begun to organize itself around writing, which made it impossible to be as self-destructive as I had in the past. I was at home, not out brawl-ing in bars, getting into dangerous situations. I could have probably done the same thing with a couple years of therapy.

Q: Several of your books have been turned into movies, and more are in the works. Unlike a lot of authors, you seem to actually like Hollywood.

A: That’s true. There are an awful lot of smart, incredibly creative people out there who know things that I don’t, and I like dealing with those types of people. But there’s also a side of me that enjoys collaboration, so I stay attached to each book as both producer and writer whenever I’m able to. As for directing, I find it’s a skill that it’s too late for me to acquire. It’s like, I just started learning to play the banjo. And I’ve had to lower my expectations a lot.

Photograph: Ileana Florescu