In the fall of 2021, my son and I went to see the Bulls play the Brooklyn Nets at the United Center. It was an attempt to find some normalcy after a year and a half of uncertainty and hiding in our house. We wore masks and showed our vaccination cards and then climbed to the 300 level, where we settled into our seats.

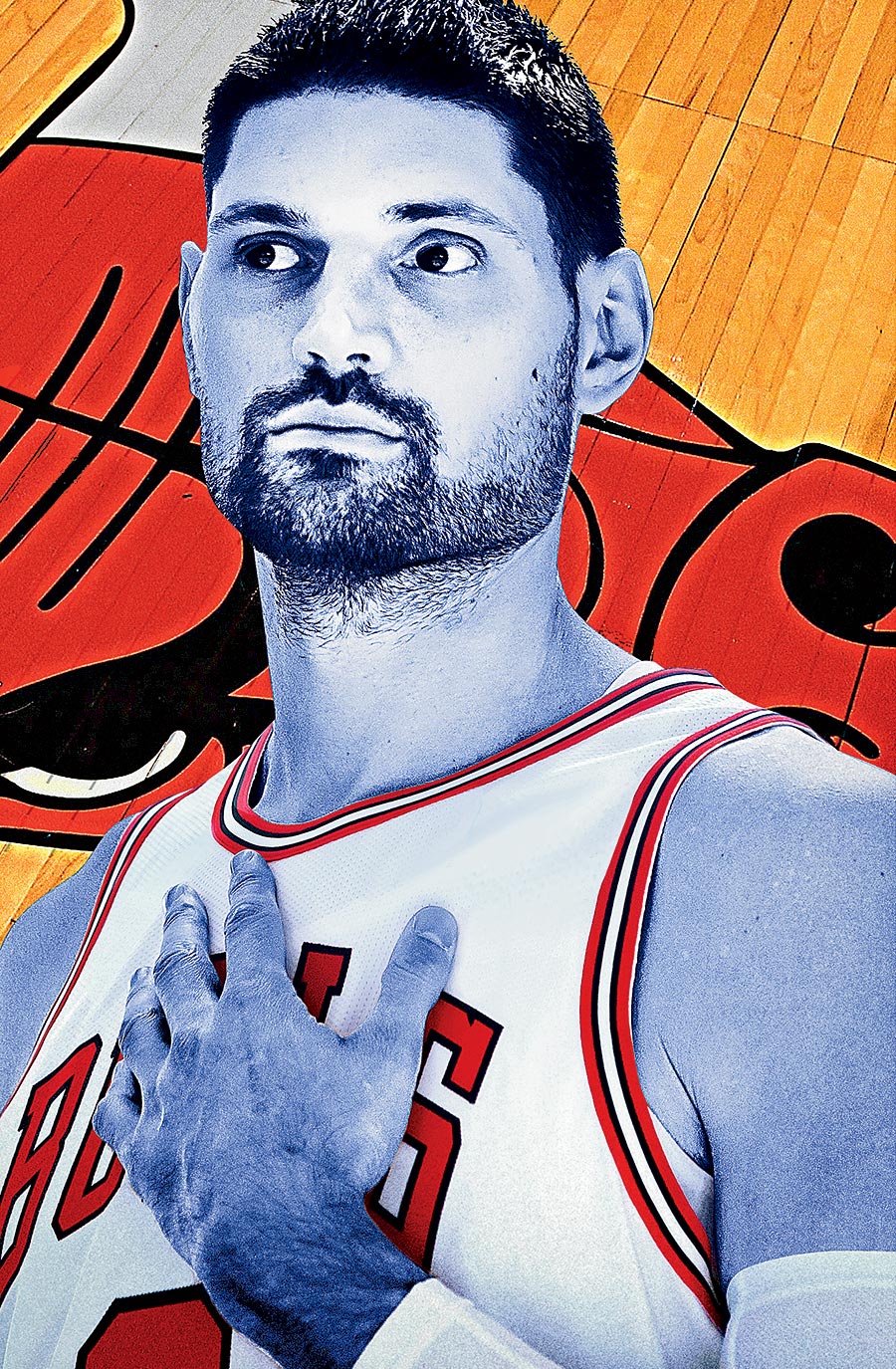

When the Bulls were introduced, stars DeMar DeRozan and Zach LaVine got the requisite cheers. But when the name of the Bulls’ recently acquired starting center, Nikola Vučević, was called, the crowd erupted into a low moan that sounded like booing. My son, then 11, looked at me: Why were fans jeering one of their own players? I looked back at him and shrugged.

Despite all of the big names on the floor — in truth, we were there mostly to marvel at future Hall of Famers Kevin Durant and James Harden, both then of the Nets — I found myself drawn to Vučević. There he was, in the middle of it all, quietly pulling down rebounds, operating with incredible efficiency in the post, bullying his way to the basket, doing the silent, often-overlooked work needed to keep his team in the game. And each time Vučević scored, the crowd erupted into the same low moan.

Finally, my son leaned over and said, “I think they’re saying ‘Vooooch.’ ”

For the rest of the game, Vooch appeared to be everywhere and nowhere, all at once. One moment, he would be at the center of the offense, attacking the basket; the next, he would fade into the background before making a well-timed assist or pick. He seemed to have an uncanny ability to be integral without being visible. Yet I found myself continually watching him. It was only later, thinking about his Eastern European roots, that I realized why the way he played resonated so much with me.

In the 1980s, when I was growing up in south suburban Evergreen Park, I instinctively knew that my heritage was not something I wanted to advertise. After all, Eastern Europe was part of an evil empire, or so Ronald Reagan suggested. Chicago, of course, has one of the largest Eastern European populations in the country, but that wasn’t the city I knew.

My Chicago was overwhelmingly Irish. The South Side’s famously raucous St. Patrick’s Day parade started just a few blocks away from where I lived, and I attended Catholic school alongside classmates who proudly wore their bright green South Side Irish jackets. Meanwhile, I couldn’t even find Croatia or Poland — the birthplaces of my maternal great-grandparents — on a map.

The world at that time was divided by an imaginary fault line between good and evil, the United States and the Soviet bloc. When we played tag at recess, it was often framed as hiding from the Communist invaders, inspired by movies like Red Dawn. I ended up becoming very good at hiding.

When I watch the Bulls’ big man, I see my immigrant ancestors. I see someone interested in letting his effort speak for itself, someone who shows up and does his job each night, incredibly well.

Both sets of my mother’s grandparents left their homelands at a moment of occupation by a foreign power: Croatia, at the time, was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Poland had been conquered by Russia. If I had tried explaining the nuances of this to anyone my age, all I would have gotten was blank stares. The only thing about Eastern Europe other kids seemed to recognize was that it had something to do with the Soviet Union and so was on the wrong side of the good-evil equation. That was not something I was equipped to counter at that age.

So whenever the topic of ancestry came up, I got quiet. My last name, which belonged to my Italian American father, helped me get away with it — and allowed me to avoid being the butt of a never-ending stream of Polish jokes.

But even at home, our Eastern European heritage was not something we ever really discussed. Unlike other Eastern Europeans in other parts of the city, we did not honor the patron saint of Croatia on St. Joseph’s Day. We did not wear red, did not go to church, did not have an altar with flowers and food. Nobody in my family seemed especially proud of our Eastern European roots.

Sometimes it felt as if my family’s history began only after my great-grandparents arrived in America, as if whatever had happened before that did not matter or was so terrible it could not be discussed. I wondered if other Eastern Europeans in the city also felt compelled to reinvent themselves in their new land, severing any detectable connection to the past. Whatever the answer, something about my family’s silence always left me with a tinge of sadness and regret.

Even before Vooch’s arrival, the Chicago Bulls changed the way I thought about being Eastern European. When Toni Kukoč came to Chicago in 1993, it was the first I’d heard of an athlete from Croatia or anywhere else in that part of the world playing a professional sport in America. His game-winning shot against the Indiana Pacers in 1994 with 0.8 seconds left (after Reggie Miller prematurely took a bow in front of Bulls fans) was the first time I remember seeing someone from Eastern Europe so publicly celebrated in this city. Kukoč’s ascension was followed by an explosion of other Eastern European players joining the NBA after the fall of the Iron Curtain. They even brought new moves (like the Euro step) that eventually transformed the game.

Vooch was born in Switzerland and raised in Belgium, but his family is from Montenegro, which, like my great-grandfather’s homeland of Croatia, was formerly part of Yugoslavia. These days, the NBA is full of Eastern European players, including some of the game’s biggest stars: namely, two-time MVP Nikola Jokić of the Nuggets and the Mavericks’ Luka Dončić. But Vooch is here, playing for a team I’ve watched since I was a kid and that I now watch with my own family. He feels like one of our own.

The deal that sent Vučević, now 33, from Orlando to Chicago in March 2021 was heavily criticized from the start. Analysts and fans argued that the Bulls had given up too much: not just two important role players, but two first-round draft picks. Pundits questioned the value of building a team around a center whose greatest assets seemed to be his ability to rebound and his understated consistency.

Over the past three seasons, as the Bulls have slipped from outside contenders to also-rans, the criticism hasn’t gone away. But winning was never the reason I was drawn to Vooch — it’s much more personal than that. When I watch the Bulls’ big man, I see my immigrant ancestors. I see someone interested in letting his effort speak for itself, someone who shows up and does his job each night, incredibly well.

During the 2021–22 season, his first full year in Chicago, Vučević averaged 17.6 points, 11 rebounds, and 3.2 assists per game. The next year, he averaged — somewhat impossibly — 17.6 points, 11 rebounds, and 3.2 assists per game. That’s the kind of consistency my Eastern European great-grandfathers would have reveled in. As workers at the U.S. Steel plant in South Chicago, they did their best to assimilate, stay anonymous, and let their labor tell their story.

Vooch helped me realize that perhaps it wasn’t embarrassment or shame that kept my relatives quiet about their heritage all those years; maybe it was just the way they went about their business. By attending to all the little things, by performing the invisible tasks on a highly visible stage, Vooch validates what Eastern Europeans have been doing in this city for more than a century. And because of that, win or lose, I’ll be watching.