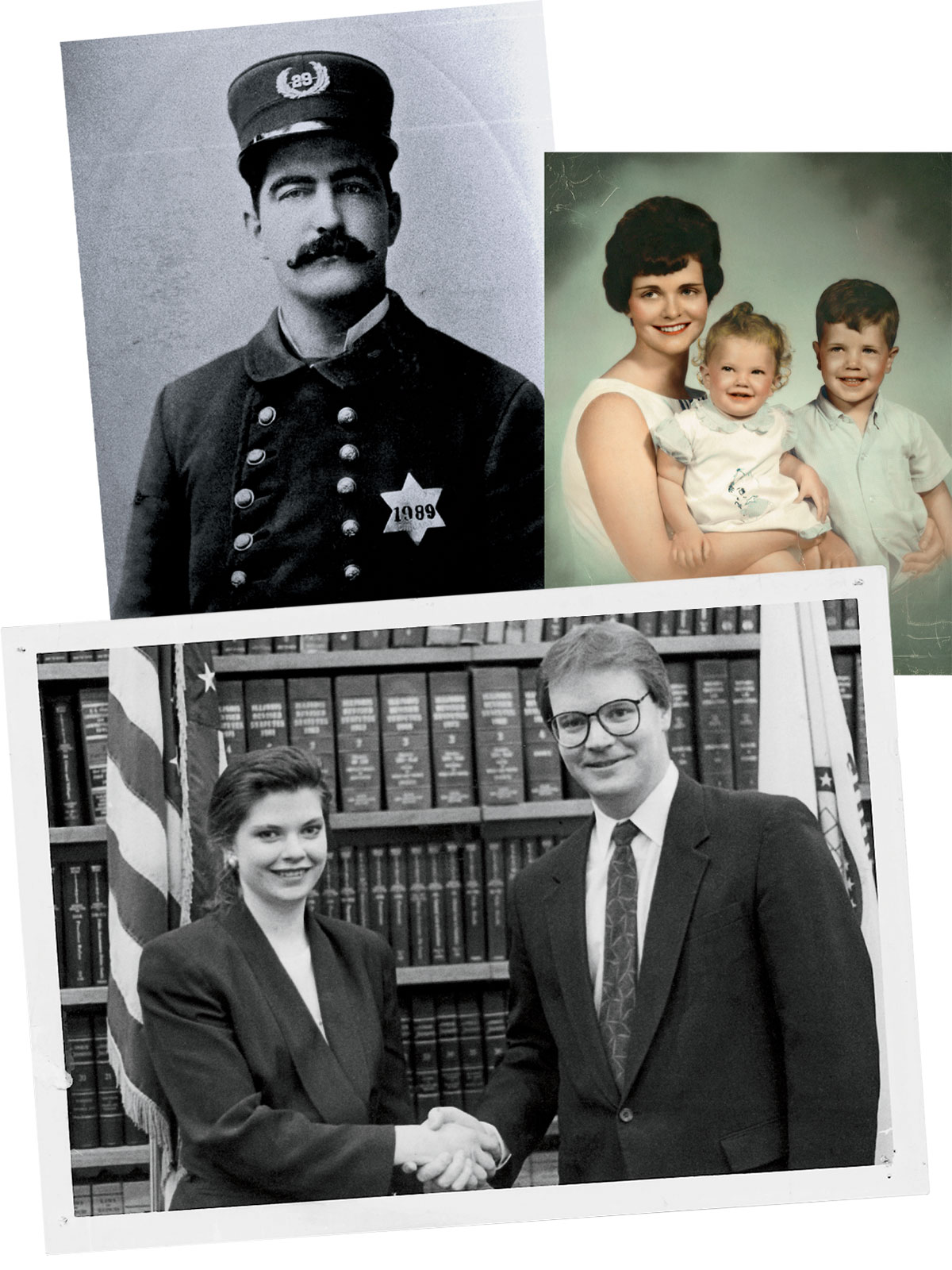

A few days before Eileen O’Neill Burke would be elected the new Cook County state’s attorney, the top prosecutor in a jurisdiction of 5.1 million people, she tells me a story about her great-grandparents. We’re sitting in her campaign office on North Dearborn Street, where O’Neill Burke has laid out 15 old family photos on an otherwise bare table. Among them are antique studio portraits of her forebears, a snapshot of her as a young girl with her older brother outside their home in Edgebrook, and a recent picture of her with her lawyer husband, John, and their four children, in their teens and early 20s, all beaming. Two of O’Neill Burke’s top staffers crane over the table to see the photos for the first time.

Modern political strategies put family histories and personal struggles at the center of campaigns — the more bittersweet, the better. Yet O’Neill Burke did not run on her personal story. For over a year in candidate mode, she rarely mentioned the people or chapters that forged her morals or mettle. Instead, her pitch was her record as a lauded judge and her outrage over a justice system that she argued was enabling too much theft and violent crime. The photos, though, reveal another wellspring for her yearnings to help the region: her own family’s century-and-a-half history in Chicago. For O’Neill Burke, 59, that history hardly feels distant. It lives on inside her. She relates it with the emotional intensity of someone recapping her own story of love and heartache.

She points to a portrait of her maternal great-grandmother, who, as an infant, survived the Great Chicago Fire in 1871. She lights up at the 140-year-old image of the teen beauty donned in a richly embroidered dark silk dress, a large Celtic cross pendant, and a tight Queen Victoria hairdo with a teacup top. Like her modern kin, Great-Grandma has delicate features and eyes that glint. “Her name was Hannah Fitzgerald,” O’Neill Burke says emphatically. “She married my great-grandfather — a cop.” O’Neill Burke has a collection of buttons from his police jacket.

After the fire, O’Neill Burke’s ancestors moved to the newly developed Austin area on the West Side. Last year, Austin had 47 homicides, more than any other neighborhood in Chicago. Early in her campaign, O’Neill Burke visited Austin for a meeting with a Cook County commissioner. While there, she stopped by her family’s old house, where she introduced herself to the current residents, telling them her family had lived in the home for 100 years. One of the residents issued a plea. “When I told him who I was, he said, ‘You have to stop the shooting here,’ ” O’Neill Burke recalls. “And it kind of brought it home. I’m not just doing this for one ZIP code or one neighborhood. We can make a difference throughout the entire county.”

O’Neill Burke has said she’ll fight crime by addressing its root causes, but she also likens Chicago’s murder rate to “war zone” numbers, even as the number of homicides dropped from 620 in 2023 to 573 last year, according to the Chicago Police Department’s preliminary data. She has promised to crack down on “weapons of war,” the increasingly prevalent guns illegally modified to spray bullets at high speeds. She spoke often during her campaign of how murders, along with rampant retail thefts, carjackings, and assaults, not only are tragedies for particular victims or neighborhoods but also choke the vibrancy and prosperity of the whole region. Moments after her swearing-in on December 2, she offered a forceful declaration that her office will be far more dogged in pursuing charges, jail detentions, and convictions for theft, domestic violence, child abuse, and gun crimes. Most important, she said, is her office’s determination to make sure defendants possessing those fearsome modified guns are held in jail while awaiting trial.

Though a lifelong Democrat, O’Neill Burke wasn’t the establishment pick in the primary. The Cook County Democratic Party backed University of Chicago lecturer Clayton Harris III, a progressive deemed more ideologically suitable by the party’s head, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, who had anointed O’Neill Burke’s predecessor, Kim Foxx. Preckwinkle labeled O’Neill Burke a “de facto Republican,” warning that she would reverse more than a decade of reforms and “move us backward.” The strategy failed, albeit narrowly: O’Neill Burke beat Harris in a nail-biter primary by just 1,571 votes.

O’Neill Burke likens taking over the role to cleaning out a really big closet. “This is making order out of chaos on a bigger scale. We have four years to get this right.”

During her campaign, O’Neill Burke was widely perceived — by her opponents and by some of her supporters — as a hard-charging, tough-on-crime candidate pitted against “soft-on-crime” progressives. O’Neill Burke rejects that mantle, but allows that an inner toughness is a prerequisite for the job. “I became a cold, hard woman from being an assistant state’s attorney,” she says, referring to her time handling abuse and neglect cases. “That was probably the hardest five months of my life, but it gave me a little bit of shield. As horrific as it is, I have a job to do, and I think most prosecutors get a bit of a shield or they couldn’t do their job.”

Voters who imagined O’Neill Burke cracking skulls and filling prisons have ignored her stated commitment to counseling and training programs as alternatives to incarceration. If her tenure heralds a new era for the state’s attorney’s office and law enforcement in Cook County, it will likely be because she weds strong, effective law enforcement with many of the same long-term social programs that progressives see as necessary.

That’s hardly a simple balance to strike. O’Neill Burke takes office at a time when there is division in Chicago and the county, among both leaders and residents, on how to address crime. The Chicago Police Department remains under pressure to comply with a wide-ranging federal consent decree, negotiated following the 2014 police killing of Laquan McDonald and a subsequent federal investigation that uncovered pervasive patterns of unconstitutional policing, particularly in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods. It’s just one aspect of the tension between progressive reformers who have pushed for structural changes to the justice system and those alarmed at crime rates who say the priority should be pursuing more arrests. For O’Neill Burke, there’s nothing easy about what lies ahead.

The new state’s attorney doesn’t like to travel with a big entourage. Even while campaigning, O’Neill Burke eschewed the people trains that, à la Veep, often follow local political big shots. When the South Loop resident set off on the morning of October 31 to cast an early ballot in the general election, she drove alone, in her unassuming 2016 Volvo, to vote at Dawson Technical Institute in Bronzeville.

Her understated arrival that morning belied the stakes of the contest, though as usual in Cook County, taking the Democratic primary had all but assured she would prevail in the general election. By winning with a tough-on-crime message, she proved to be the kind of Democrat with broad appeal that pundits have declared the party desperately needs. For her part, O’Neill Burke says the state’s attorney job is the only office she’d vie for. She has, she claims, no political ambition beyond the law.

Perhaps one reason O’Neill Burke did not reach into her personal story to round out her appeal to voters was that she didn’t think that well was all that deep. “I’m really not that interesting,” O’Neill Burke told me at one point. It’s a tough sell. After she cast her ballot, I watched as she walked outside to meet Alderpersons Bill Conway, Pat Dowell, and Nicole Lee — all of whom found her compelling enough as a candidate to buck their party leadership and back her. O’Neill Burke asked the trio to wait a moment on the curb. She walked to her car, reached into the back, and pulled out a potted plant for each of them. “I grew these,” she said as she thanked them. They were visibly surprised. “You grew these?” they seemed to say at once.

One wonders if they know what O’Neill Burke’s best friends do: that she used to sew some of her own clothes and thrills at the chance to assemble furniture. What the trio put their faith in was O’Neill Burke’s appetite for the daunting task, as they saw it, of rebuilding an essential county office that had lost staff, struggled with recruiting, and been beaten down by pundits and the police for being soft on crime — and that desperately needed a refresh.

In some ways, O’Neill Burke seems an unlikely person to take on the task. Her path to becoming the Cook County state’s attorney has been a drive to stay above the state’s bruising politics rather than to dive in. She got her start as a Cook County assistant state’s attorney in the ’90s, then went into private practice as a defense attorney before being elected a Cook County judge. In 2016, she became a justice of the 1st District of the Illinois Appellate Court in Chicago. She is the only state’s attorney to have forfeited a secure, exalted, higher-paying top judgeship, along with the hundreds of thousands of dollars in pension money that would have come with it, to take the job.

Why did O’Neill Burke give up her judgeship to run for state’s attorney? “It’s kind of a mix of personal, spiritual, ethical, and civic duty to respond to a crisis,” says her husband.

So why did she? O’Neill Burke began to think about running for state’s attorney even before Foxx announced in April 2023 that she would not seek reelection. She kept the idea mostly to herself, but found it hard to shake. “When you’re in a position to do good, I think you have to take it,” she says. If Foxx had decided to run, O’Neill Burke might not have challenged her, but when the path opened up, she felt compelled. The final decision surprised her friends and family. Her husband, John Burke, a civil attorney, learned by phone and recalls saying: “Wait, do you really want to give up one of the best jobs in the world, where people call you ‘Justice’? Do you really want to take over the state’s attorney’s office that has all sorts of issues?” The only way he can make sense of the decision is to view it as a calling. “It’s kind of a mix of personal, spiritual, ethical, and civic duty to respond to a crisis,” he says.

In the ’90s, when O’Neill Burke first joined the office, assistant state’s attorneys tended to stay in the job a decade or more. That has not been the case of late. Departures compounded during the pandemic, as they did in other big-city prosecutors’ offices across the country. According to an October 2022 report from NBC-5, the Cook County state’s attorney’s office lost 235 staffers over the previous 15 months, leaving the organization short one-fifth of its budgeted positions. Even since the pandemic, the churn of young lawyers in the office remains accelerated, with many frequently leaving before their three-year mark. The turnover is devastating for an office where experience and institutional memory are key to handling a high volume and wide variety of cases.

Recruiting qualified replacements has been slow, though in late November, in the twilight of the outgoing administration, 48 assistant state’s attorneys were hired, filling many of the vacancies. It will fall to O’Neill Burke, who attended the swearing-in and posed for a photo with Foxx, to train this new class and to create an environment that encourages ASAs to stay on longer. The latter will be a challenge considering their salaries are less than half those of new hires at Chicago’s top private firms.

In her campaign rhetoric, O’Neill Burke often emphasized weedy topics related to the running of the state’s attorney’s office. She stressed, for instance, how she would continue to educate both new and seasoned lawyers by bringing in retired judges and former assistant state’s attorneys to teach them and by creating a lively online education platform, something like Khan Academy, that would digitize, even gamify, learning. She promised to upgrade the office’s technology so that it could gather and make better use of data from the police and local agencies. “She talks about training all the time — voters might not get it, but ASAs get it,” Alderperson Conway says. “It has little to no political power, but it’s important in making the office function well.” O’Neill Burke was sending a message to the staff she knew she would be inheriting: She would aim to restore the office’s reputation and turn it into the best and most admired in the nation.

A common complaint O’Neill Burke heard from alumni of the office was that it was caught in a downward spiral of attrition. Indeed, Foxx herself frequently lamented that her staff was forced into triage mode, focusing resources on violent gun crimes. The perception that the office was incapable of handling the broader scope of crime was one of the main reasons O’Neill Burke decided to run. She likens taking over the role to cleaning out a really big closet. “That’s one of my favorite things to do. My husband knows that when I go down to the basement and I don’t emerge for three or four hours, it’s going to be all reorganized and that I love that it is. That’s exactly what this is like. This is making order out of chaos on a bigger scale, and we’re on a very tight schedule, too. We have four years to get this right and make a difference.”

A fourth-generation Chicagoan, O’Neill Burke is a self-described local history nerd. Her own family’s tale has been indelibly shaped by members of law enforcement. The second photo she pulls out of the picture pile is of her maternal grandmother, a model for Marshall Field’s. In one studio portrait of her in a light-colored, formfitting silk gown, she looks like a silent film star. “She would go outside of work onto State Street,” O’Neill Burke says. “My grandfather was a mounted policeman, so she used to go to the cafeteria and get sugar cubes for his horse. That’s how their romance started.”

The blue line continued into the next generation. O’Neill Burke’s mother, Carroll, was working as an emergency room nurse at Loretto Hospital in Austin when a police sergeant named Albert O’Neill came in, having heard one of his men had been hurt. That’s how O’Neill Burke’s parents met. “My mom said that she used to get all dressed up and be ready to go, but my dad would come over and sit with my grandpa and they’d talk cop talk for like an hour and a half.”

O’Neill Burke’s mother and father divorced when she was 5. Her father left the police force and became a vice president in the union for hotel workers and bartenders. He died five years later. “I was really just raised by my mother,” O’Neill Burke says. She shows me a picture of herself as a young girl in white on a sidewalk in Edgebrook on her way to her First Communion. Many of the city’s Irish cops — often with big families — had homes there.

“I think growing up in a smaller family with just my mom, my brother, and me is what contributed to me wanting to have four kids,” O’Neill Burke says. “I was probably one of the only kids in the neighborhood who had a single mom. It was unusual then and not really acceptable.” Her mother, O’Neill Burke says, was treated like the Hester Prynne of their deeply Catholic neighborhood. “She still refers to herself as a widow and doesn’t tell people she was divorced.”

A bookish girl, O’Neill Burke thrived on the structure of school. “I was never a terribly popular kid. I was always kind of bossy, which won’t surprise anybody. I was a little bit of a know-it-all. I’d read all the simple biographies of presidents and memorized as many facts as I could. I would tell kids things like ‘George Washington had four hunting dogs.’ ”

O’Neill Burke’s mother returned to school for a bachelor’s and a master’s in nursing. “My mom worked full-time, so my brother and I got very good at making TV dinners,” O’Neill Burke recalls. Carroll eventually rose to be a head nurse at Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center, leading the intensive and acute care units.

O’Neill Burke attended local Catholic schools until her junior year of high school, when her mother took a position in Santa Fe with the federal Indian Health Service, the principal health care provider for Native Americans. Carroll often traveled with her kids to Puebloan communities for feast days and ceremonies. Living beyond Edgebrook and local parochial schools for the first time, O’Neill Burke was riveted by how Catholicism blended with the Puebloans’ traditions and narratives. “At the Taos Pueblo, north of Santa Fe, for Christmas they would reenact how tribesmen would block the electric company from coming into their pueblo, blocking roadways and firing shotguns.” Experiencing holidays from the perspective of another culture was a revelation. Through her mother, she says, “we were exposed to all different kinds of people, and that really influenced how I approach people, too.”

O’Neill Burke returned to Illinois to attend the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She paid for tuition with money from her father’s life insurance and her work as a cocktail waitress. Her mother moved to Maryland for a job evaluating medical devices for the Food and Drug Administration. “Others would come to the FDA and work for a few years, then work for a company trying to get approval for different devices,” says O’Neill Burke. That “absolutely disgusted” her mother. “It was a good lesson: Money isn’t the ultimate thing. Doing what you think is right is the ultimate prize.”

I ask O’Neill Burke if her forebears that served in the public sector did so out of a sense of obligation or community. “That’s what they knew and what was available to them,” she says. “But that sure wasn’t my mom. She could have done anything she wanted, and she chose to be in public service.” And she remains O’Neill Burke’s guiding light. “She did things sort of like Ginger Rogers,” O’Neill Burke says, invoking the famous quip about the actress doing everything Fred Astaire did but backward and in heels. “My load was much easier than my mother’s. When I look at her in comparison, oh, she worked so much harder, under so much pressure against all kinds of things that might have overcome her at any time.”

O’Neill Burke’s interest in the law also began with her mother, who, she says, always wanted to be an attorney herself. “There’s no doubt in my mind that she planted the seed very early.” In sixth grade, O’Neill Burke heard Cook County Circuit Court Judge Mary Ann McMorrow speak at her brother’s eighth-grade graduation. “It was still the ’70s and there were not many female judges,” O’Neill Burke says. “I came home and told my mother I wanted to be a judge. I followed that voice and never deviated from that.”

In 1991, after graduating from Chicago-Kent College of Law, O’Neill Burke joined the Cook County state’s attorney’s office, initially working on appeals. O’Neill Burke was one of a few dozen hires at the time, culled from more than 2,000 applicants. When she went to argue her first case in appellate court, the judge was none other than McMorrow, who eventually became the first woman to serve on the Illinois Supreme Court. “I was so starstruck,” O’Neill Burke recalls.

The state’s attorney’s office, with more than 600 attorneys and 600 other employees when fully staffed, held much prestige at the time. It had long been a famous, and coveted, training ground for trial attorneys, with federal prosecutor Dan Webb and former Mayor Richard M. Daley among its notable alums.

Early in O’Neill Burke’s tenure, the state’s attorney, Jack O’Malley — a rare Republican in a countywide office — put her on the team working to wrest information on pedophile priests from the Archdiocese of Chicago, which had run its own investigation into allegations against them. “This was long before the [Boston Globe] Spotlight investigation, and O’Malley was one of the first to look into allegations,” says O’Neill Burke.

Cook County Associate Judge Renee Goldfarb, then a supervisor in the office, was struck by O’Neill Burke’s tenacity on the case. “Eileen was like a dog digging for a bone,” Goldfarb recalls. The team lost its effort to gain access to the documents for use in prosecution when a judge ruled that they were protected under “priest-penitent privilege,” established by state law. But the state’s attorney’s office had become aware of how the archdiocese had been complicit in the sexual abuse, shuffling priests accused of molestation off to new parishes without informing those congregations of the allegations. “As somebody who had grown up Catholic, it was shocking,” O’Neill Burke says. “It was absolutely abhorrent what was going on.”

It was enough to compel O’Neill Burke to leave the Catholic Church. Her husband stayed for a while, but eventually he left, too. “I do make a point of saying I’m not a Catholic, because it is an easy assumption to make,” she says. “You know, I grew up Catholic. I went to Catholic schools. I’m Irish. I have a lot of children.” She and her family later joined a Park Ridge church that she describes as “mainstream Protestant.” Over the years, she and her husband have taken mission trips to Central America, the Caribbean, and eastern Kentucky coal country.

In 2001, to try to spend more time with her children, O’Neill Burke left the state’s attorney’s office to go into practice for herself as a defense attorney, handling criminal and occasional civil cases throughout northern Illinois. She credits her eight years in that role with giving her a more comprehensive view of the legal system. “Defense forces you to look at the law from a completely different angle,” she says. “You start to learn how to test a case. Do we fight tooth and nail? Do we have a basis to fight? When do you file a motion to suppress? Do we just try to mitigate the harm at this point?” Unlike prosecutors, who are assigned to specific courtrooms, private defense attorneys have often not met the judge before a trial. “Some judges,” O’Neill Burke says, “may never give them a break no matter what they do. So you have to learn all this stuff to be effective.”

As O’Neill Burke runs through chapters of her life with me, she inevitably veers instead into the issues that drove her to campaign for the state’s attorney job. She seems uncomfortable talking about herself. O’Neill Burke’s longtime best friend, Clare McWilliams, an ex-judge who served nearly 19 years on the bench in Cook County, describes her as an introvert. Fittingly, the legal jobs O’Neill Burke liked best were the more scholarly ones: She relished working on appeals as an assistant state’s attorney and later serving on the appellate bench. “You get to know the legislative history of where a statute came from and how case law evolved and changed,” O’Neill Burke says. “You could see legal trends in a way you can’t see them in the trenches of trial court.”

Yet, in conversation, O’Neill Burke’s warrior streak, the one that voters read as “law and order,” bursts out. She grows intense and sometimes wildly animated about digging into the tasks ahead. She sits on the edge of her chair, her eyes twinkle then grow fierce, her arms freely punctuate her plans.

Once O’Neill Burke took office, she didn’t waste time in reversing one of Foxx’s most controversial policies: the $1,000 threshold for felony charges in retail theft. Under Foxx, thieves caught with goods worth less than that were charged only with misdemeanors, unless they had 10 prior felony convictions. O’Neill Burke, who often noted that thieves could clear a whole shelf at Walgreens and remain under the $1,000 mark, returned the minimum to the legislatively mandated $300. Where Foxx saw necessary triage, O’Neill Burke saw an invitation to steal.

The numbers indicate she may be on to something. The Illinois Retail Merchants Association touted estimates that the state’s retailers lost $2.9 billion in revenue to theft in 2022. In Chicago, while reports of theft overall were slightly down, retail incidents climbed by nearly 50 percent from 2023 to 2024, reaching their highest level in 20 years. Local newscasts regularly aired dramatic footage of smash-and-grab heists at luxury stores, some involving gangs of thieves who leaped out of cars they had crashed through store windows. In 2021, Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul established a task force on retail crime, noting that rising theft from big-box stores, pharmacies, and car dealers was linked to organized crime rings that used store robberies to underwrite drug and human trafficking and other illicit activity.

O’Neill Burke maintains that in the long term, significant reductions in crime will depend on a more comprehensive approach. “We’ve got to get the ship righted, and then we can go after recidivism.”

“Perception is reality,” says Joe Ferguson, head of the Civic Federation, a Chicago-based nonpartisan research organization. “You can grab data on crime going down, but the perception is that there is greater criminality in Chicago neighborhoods and the city is struggling with crime. The business community needs predictability, and the state’s attorney has to articulate a vision to business.” That’s something O’Neill Burke has been able to do that Foxx wasn’t.

O’Neill Burke was also incensed by Foxx’s handling of gun cases. The new state’s attorney has vowed to aggressively pursue charges and detention for felonies, particularly in cases related to gun violence. (Foxx’s office dropped charges against nearly one in three — more than 25,000 — felony defendants during her first three years in office, the Tribune found in 2020.)

Other reforms enacted in recent years are here to stay. Progressives, for example, successfully pushed for the Pretrial Fairness Act, which eliminated cash bail in Illinois, meaning that those accused of all but the most serious crimes are no longer held in jail while awaiting trial only because they cannot afford to post bail. O’Neill Burke supports the act, though on her first day in office, she announced a policy change: Prosecutors would now automatically seek pretrial detention for anyone accused of certain crimes, ranging from murder to felony offenses committed on public transit.

She maintains, though, that in the long term, significant reductions in crime will depend on a more comprehensive approach. Prosecutors, she believes, ought to be well versed in the available alternatives to incarceration, as well as the tools for reintroducing convicts back into society. “What do they need?” she asks. “There are things we can be taking care of in the six months prior to their release. Do they need a GED for a job? Let’s figure it out. If we’re not addressing somebody’s needs before they come out, we’ll be in the same revolving door.” Much of that work, she says, will come down the road. “We’ve got to get the ship righted, and then we can go after recidivism.”

Still, even now, she has been visiting local community groups that offer counseling and job training to recently released convicts. Teny Gross heads the Institute for Nonviolence Chicago, an organization active in Austin that has nearly 2,000 people with criminal backgrounds on its payroll or on stipends providing outreach to violence victims, gang members, and ex-cons. Gross says Foxx’s office sometimes referred offenders to its programs, but he sees the potential for even deeper engagement with O’Neill Burke. “She’s different from politicians in the 1990s,” he says. “An important test for her is that she doesn’t fall into the simple scenario that she is a tough-on-crime person. She can carry a big stick and use it sparingly.”

It was this more nuanced approach that attracted some of O’Neill Burke’s key supporters, including 3rd Ward Alderperson Dowell, who risked the ire of fellow Black elected officials by endorsing O’Neill Burke over Harris in the primary. “I represent a community that speaks to me often about gun violence, carjackings, and smash-and-grabs,” says Dowell, whose ward runs from the South Loop at Roosevelt Road to Washington Park on the South Side. “Eileen’s not a politician, and that was something very attractive about her campaign. I sat down with her, and she didn’t give me pat, canned answers. She shared her ideas around restorative justice and training. The more you talk to Eileen, the more you learn she has the passion to do it.”

It’s mid-December, and O’Neill Burke is at a meeting of the 18th Police District Council, making one of her first major public appearances after taking office. Created in 2021 for each of the city’s 22 police districts, these elected councils allow for civilian oversight of the department. This particular district includes the Mag Mile and many of the more affluent Near North Side neighborhoods that have suffered from spikes in retail theft. Around 200 people — mostly middle-aged and older and mostly white — fill a big hall at the Moody Church in Old Town.

O’Neill Burke’s days of traveling solo are on pause. Patrol cars park outside, and a security detail spreads out through the hall. Still, the atmosphere beforehand is friendly. A group of local officials congratulates O’Neill Burke and sheepishly asks her for selfies. She obliges.

The meeting starts with a declaration from one of the three council members about how glad he is that O’Neill Burke was elected. The crowd greets her with loud, sustained applause. O’Neill Burke opens with her love for Chicago and why the county’s high crime rate and the dysfunctional justice system compelled her to leave her judgeship. She adds that she is not cut from a politician’s cloth. “I like to compare the appellate court to a lovely pickleball tournament, and the race for Cook County state’s attorney to a Klingon death match,” she jokes.

O’Neill Burke hardly pauses for the laugh before laying out her top priority: guns. In particular, stopping the proliferation of handguns modified with what’s known as “Glock switches” that shoot an uncontrollable spray of up to 20 rounds a second. “On day one, December 2,” she says with a heavy measure of prosecutorial force, “we changed our policy. Every single time someone is found with one of these guns, we ask for detention. We can change the behavior by enforcing the law.” This declaration provokes even louder applause.

One questioner asks O’Neill Burke whether she expects support from Mayor Brandon Johnson’s office, almost certainly an inquiry into her relationship with the local progressive leadership. “I won a constitutionally elected office,” she answers, “so nobody dictates state’s attorney policy other than me.”

More applause. O’Neill Burke’s stick-to-the-law message is one that large numbers of residents have been waiting for. And one that others — those who hoped progressive change would restore communities failed by previous generations of policing and prosecution — remain wary of. But O’Neill Burke now wields the power of the state and has a bully pulpit to build trust and bring the county together on the issue of crime.

The big test, of course, is whether she will make the county safer. In that fight, she’ll have to contend with not just ideologues and political interests who oppose her approach but forces far bigger than any individual: the complex web of factors that determine crime rates. The whole city — the whole nation, really — will be watching.