My first encounter with the Lyons Den came in late summer 2003. I had just turned 24 and, as a recent graduate of the University of Iowa, was looking for a job in Chicago. But with a communications degree and no real employable skills or life experience to speak of, the only offers I received were from a suburban Chevy dealership managed by my friend’s dad and a shady pyramid scheme masquerading as an advertising company. I went with the “advertising company” since I didn’t know anything about cars. Or pyramid schemes.

After my interview, where the only question I was asked was whether I considered myself a leader or a follower (I said a leader, thank you very much), I rushed down the Kennedy Expressway to the Irving Park exit, glancing frantically at the directions I’d written on a napkin, because I was already late to sign up for a comedy open mic at the Den.

I parked on a side street and started running toward the bar, still in my interview suit. When I arrived, I was almost positive I was in the wrong place. Through the front windows, it looked more like a dive bar on a slow night than the “big open mic” I’d been promised. I was greeted by the person who had told me about it, Mike Holmes.

“The show already started,” he said. “And there are already like 35 comics on the list.”

“Where’s the show?” I asked, feeling more confused than disappointed. And did he say thirty-fucking-five comics?

“Back there.” He pointed. “There’s a big room with a stage.”

Unbeknownst to me, back there in the big room with the stage were people who would be my roommates, my lifelong friends, and the best man and officiant at my wedding. Back there were also future stars — comedians who would get their own movies and TV shows and specials on HBO, Comedy Central, and Netflix (which barely existed in 2003). It would be the first place I’d ever truly fit in.

The reason I was here in the first place was that I’d met Holmes the previous summer in Iowa City, where I hosted a comedy night at a campus bar called the Summit. If there was a comedy scene in Iowa City to speak of then, it consisted of just me, Holmes, and, like, one or two other dudes. We all loved Mitch Hedberg and Dave Attell, we’d all seen the Jerry Seinfeld documentary Comedian a thousand times, and we would all make monthly treks to Penguin’s Comedy Club in Cedar Rapids to do its open mic. Where we would crush, I’d like to add. At least in our own minds.

Holmes and I decided to move to Chicago together to keep pursuing careers in comedy. And even though Holmes had heard good things about this particular Monday open mic from his sister’s boyfriend, I had no real reason to assume it would be any different from Penguin’s. Boy, was I wrong.

As I settled into my seat in the backroom of the Den, the 30-something host, a guy named Robert Buscemi, was onstage wearing a plain white T-shirt, dress pants, and dark-rimmed glasses. His voice had a hint of a Southern twang.

“I’m aware most of you are here tonight because you follow my blog,” he started, laying the absurdist irony on thick. “And I appreciate that. For those who don’t know, my blog fans divide themselves into two warring factions. One faction believes firmly that my best feature is my gossamer-soft body hair. Their rivals in the other camp argue with equal vigor that my best quality is my vestigial tail.”

The crowd was loving every second of it. Like, this shit was killing, but I had absolutely no idea why. I’d never even seen a hipster before. For the last year, I’d been watching mostly hack road comics doing the same borrowed or dated material in Iowa City, and now this Buscemi guy was talking about vestigial tails and gossamer-soft body hair? It just didn’t make any sense to me.

“Now, I personally believe that my best quality is my world-class Hamburglar drinking glass collection,” Buscemi continued. “But what do I know? I’m only the most innovative comedian that you’ll ever see.”

A little later in the night, a young, unibrowed Pakistani guy went up and absolutely destroyed with a joke about a bassoon. I specifically remember thinking that he could have picked any musical instrument and the joke still would have worked, but he picked a bassoon because it has the funniest name. This guy was good.

Since I’d missed the beginning of the show, I asked Holmes if that comedian, who had been introduced only as Kumail, was the best of the night so far. “Him or that guy over there,” he said, pointing to a tall, blond guy who also seemed to be around our age. “His name is Holmes, too. Pete Holmes.”

Not long after Kumail performed, a large and intimidating guy named Steve O. Harvey was introduced, accompanied by Darth Vader’s theme song. And once he was onstage, he challenged everyone in the audience to a thumb-wrestling contest. There were a handful of takers, and one by one, he defeated them all easily, laughing maniacally the whole time. That was the entirety of his act. The crowd loved it.

By the time he went up, 25th or 26th on the list, Mike Holmes was convinced he needed to have an intro song picked out for his performance. I suggested it was possible that the DJ just decided himself what to play, the way DJs do, but Holmes was adamant about selecting his own song. And when he requested “No Rain” by Blind Melon, Josh Cheney, the way-too-skinny kid in the suit working the sound booth, gave him a dirty look before he begrudgingly agreed to play it.

The song didn’t help. After he was introduced by Buscemi, Holmes launched into a pretty straightforward bit about driving his car with his mother in the passenger seat. It had worked the handful of times he’d told it in Iowa in front of friends. But it died a slow, painful death that night in Chicago, suffocated by a pillow of silence. The next joke suffered a similar fate. And by the time Holmes got to his closer about Indiana Jones, which had been absolutely bulletproof in Iowa, most of the audience had already tuned him out.

“I bombed,” Holmes recalls now. And when I disagree and try to downgrade his “bomb” to a “soft set,” Holmes clarifies that it felt like a bomb because it was the first time he hadn’t done well.

After the open mic, we went back to his sister’s apartment in Roscoe Village, where we were staying. Holmes was demoralized, and I remember sitting with him on the front stoop and having to talk him out of bailing on our Chicago plans (I told you I was a leader). And now that I think about it, it’s probably a good thing that I didn’t also perform that first night at the Den. Because I definitely would have bombed, and we might have aborted everything. Luckily, from the safety of my nonbomb, I got to give a pep talk and remind Holmes that Chicago was impossibly huge. There was still sketch and improv comedy for us to try. And, most importantly, there were probably a thousand other standup shows and open mics just like that one, scattered all throughout the city — but without the eccentric weirdos talking about the fucking Hamburglar.

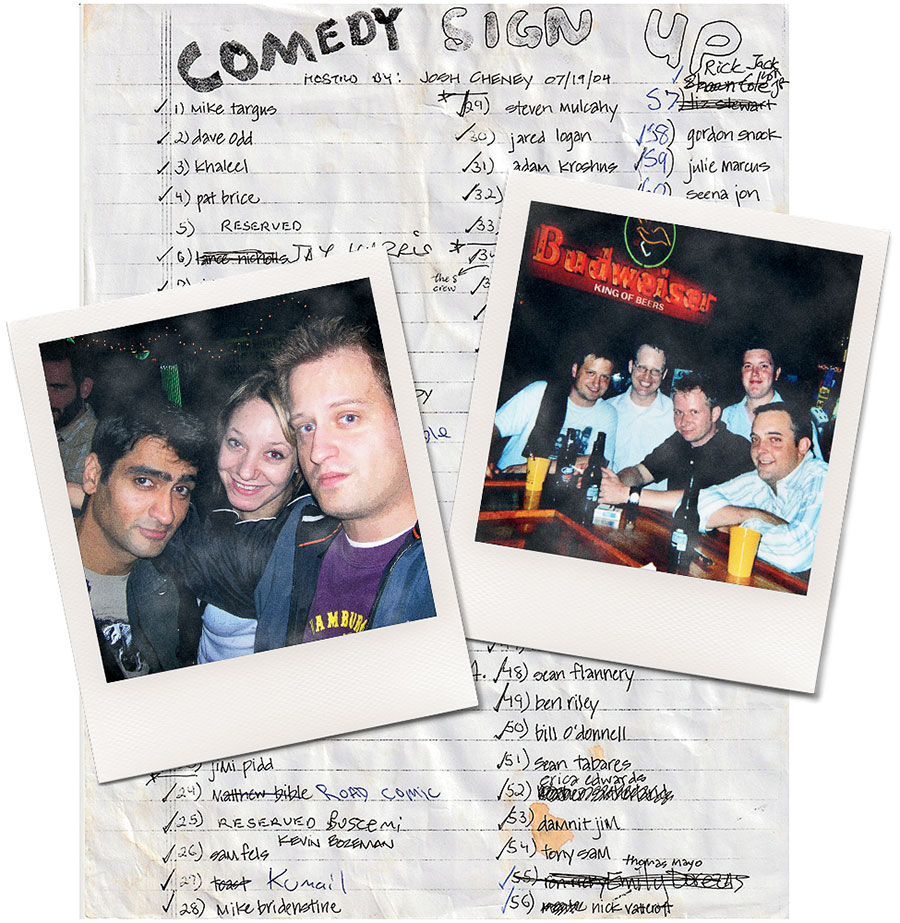

We didn’t show up at the Den again for five more months. And it slightly pains me to think of what I almost missed. In and around the same time, some of the people who would go on to become the best comedians of their generation would pass through that stage: Pete Holmes, Kumail Nanjiani, Hannibal Buress, T.J. Miller, Tommy Johnagin, Nate Bargatze, Nick Vatterott, Pat Brice, and Kyle Kinane all performed at the Lyons Den open mic on a regular basis. At some point, George Carlin dropped in just to watch. And when John Roy won Star Search earlier in 2003, he shouted out the Lyons Den in his victory interview with Arsenio Hall. It’s entirely possible that the Den, which closed in the summer of 2004, had the greatest open mic in the history of American comedy.

If the Chicago scene had a center, that was it. And I’d unknowingly just entered into it one night wearing my stupid interview suit.