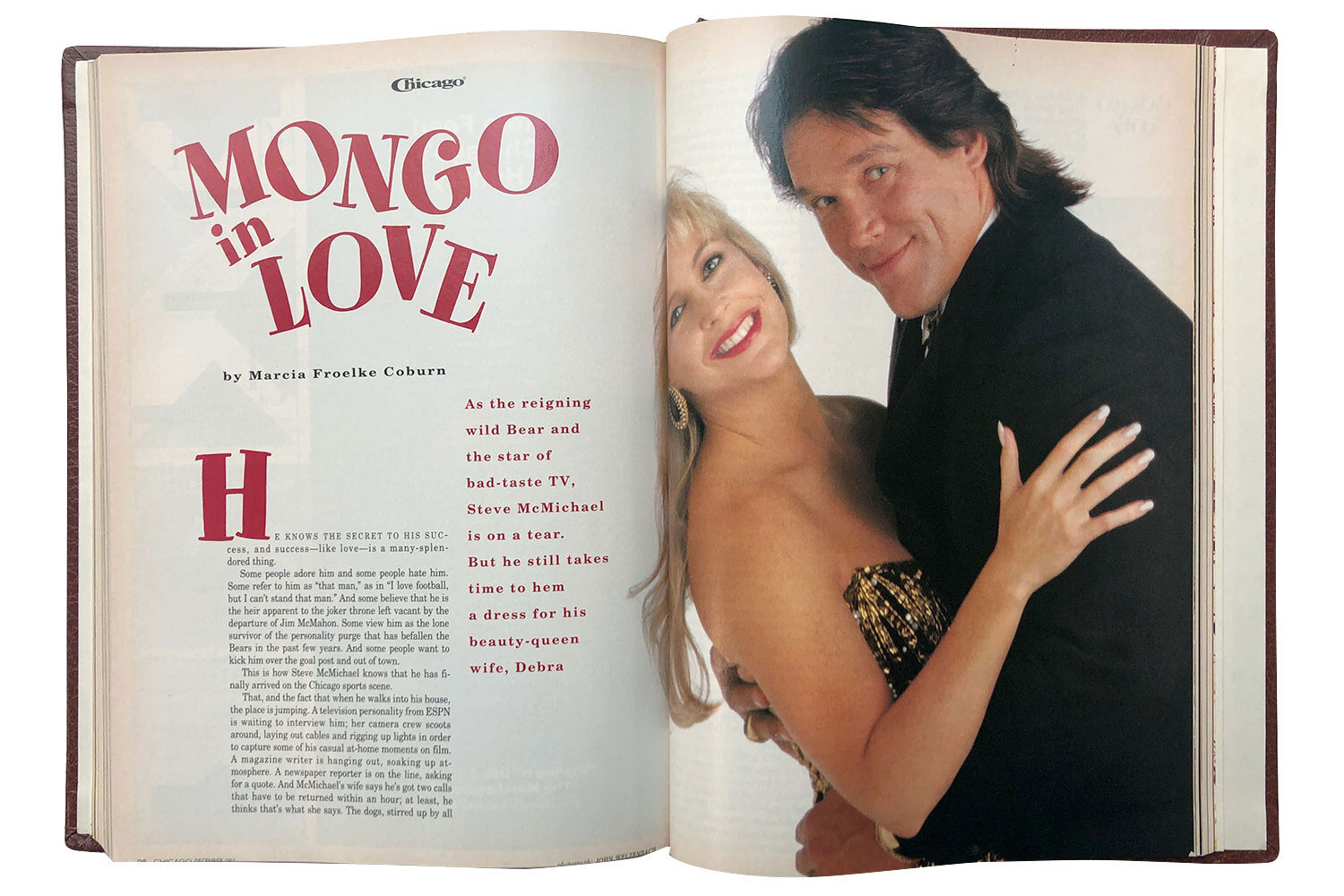

In late April, Steve McMichael, the most animated character on a 1985 Bears team loaded with them, disclosed in a WGN interview that he has been diagnosed with ALS, commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, leaving him paralyzed from the shoulders down. It was a tough sight for fans who remember him from his boisterous antics on the field and as Mark Giangreco’s cohost on NBC-5’s postgame show. Marcia Froelke Coburn captured McMichael in all his roguish charm when she profiled him for this magazine in December 1991, when he was still with his now ex-wife Debra.

He walks into the channel 5 TV newsroom and clears an enormous amount of phlegm from his throat. This is how Mongo, as he has come to be known, after the Alex Karras character in Blazing Saddles, announces his presence. Then he takes a Bowie hunting knife (a present sent to the station from WLUP radio personality Kevin Matthews) and mumbletypegs it into the top of a producer’s desk.

It is the first night of the new season — both for football and for Sports Sunday, McMichael’s show. The Bears beat Minnesota this afternoon; now a certain level of tension mixed with excitement floats through the air here. What will McMichael do tonight?

Given his past performances, it’s hard to say. He has broken a stunt bottle over Mark Giangreco’s impeccably groomed head, squirted him with whipped cream and Champagne, and held him down so that Debra could paint his mouth with lipstick. Sometimes McMichael’s Chihuahua, Pepe, has appeared on the show wearing his own miniature football helmet (painted by Debra) or a red bandanna (sewn by Steve).

A “Team Mongo” GoFundMe account has been set up for donations toward McMichael’s care.

Read the full story below.

Mongo in Love

As the reigning wild Bear and the star of bad-taste TV, Steve McMichael is on a tear. But he still takes time to hem a dress for his beauty-queen wife, Debra

By Marcia Froelke Coburn

Originally published in December 1991

He knows the secret to his success, and success — like love — is a many-splendored thing.

Some people adore him and some people hate him. Some refer to him as “that man,” as in “I love football, but I can’t stand that man.” And some believe that he is the heir apparent to the joker throne left vacant by the departure of Jim McMahon. Some view him as the lone survivor of the personality purge that has befallen the Bears in the past few years. And some people want to kick him over the goal post and out of town.

This is how Steve McMichael knows that he has finally arrived on the Chicago sports scene.

That, and the fact that when he walks into his house, the place is jumping. A television personality from ESPN is waiting to interview him; her camera crew scoots around, laying out cables and rigging up lights in order to capture some of his casual at-home moments on film. A magazine writer is hanging out, soaking up atmosphere. A newspaper reporter is on the line, asking for a quote. And McMichael’s wife says he’s got two calls that have to be returned within an hour; at least, he thinks that’s what she says. The dogs, stirred up by all the strangers and hubbub, are yapping at his feet.

And before he’s even had a chance to figure out what comes first, there is a knock at the door — a couple of neighborhood kids need some autographs on their bubble-gum cards.

It has been a long time coming, all this attention. And now that it’s here — now that he is the man of the moment, the team, the town — Steve McMichael can’t help but resent it.

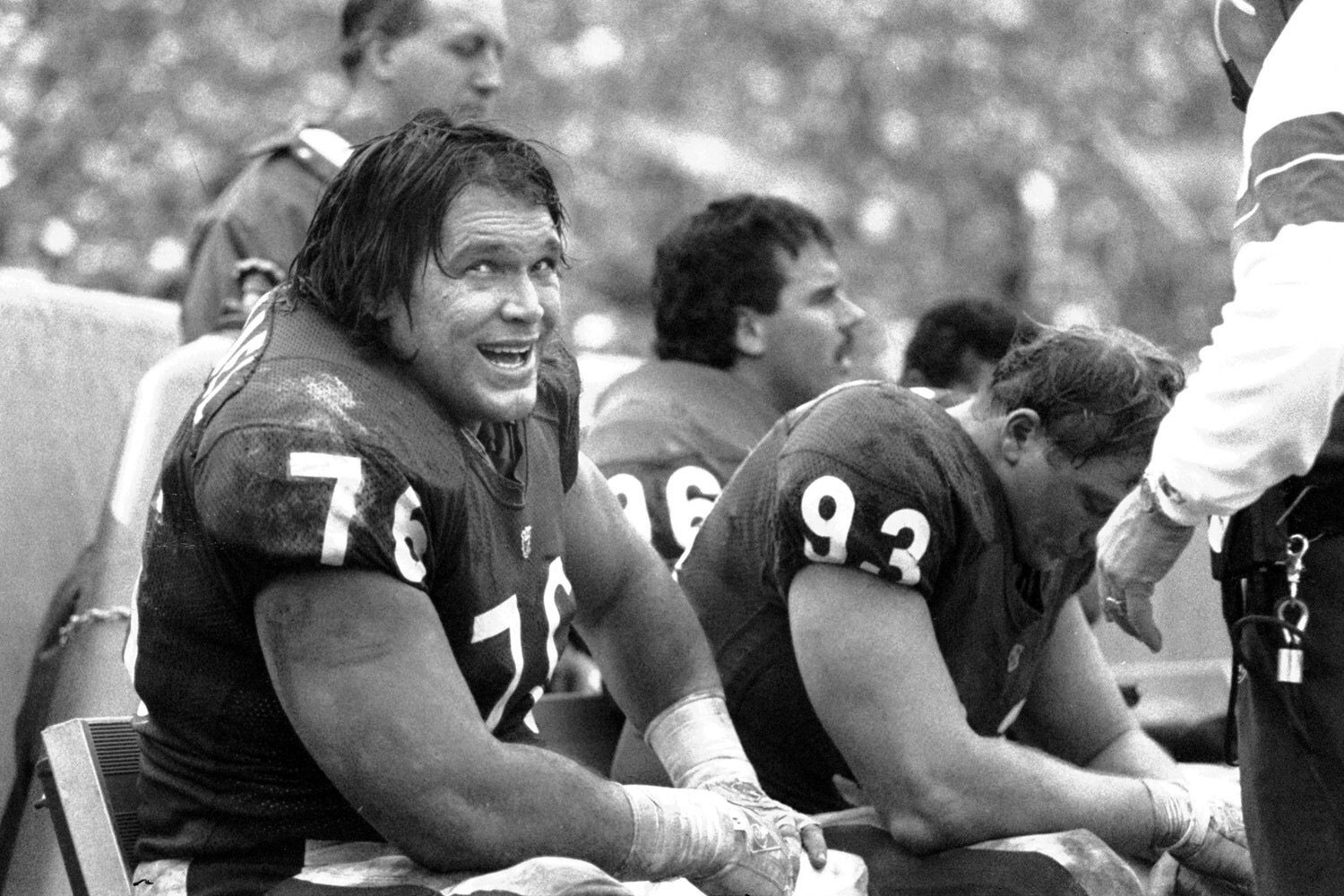

“Where’s everybody been for the past ten years?” asks the veteran defensive tackle for the Bears. “I’ve been here, starting every game since 1981. I’ve paid my dues through all these freeze-ass winters.” It’s not as if he has just emerged from a slump. He has been named All-Pro twice; he was part of the team that won the Super Bowl in 1986. For the past two years, he has ranked either first or second in defense on the Bears’ in-house rating system.

He could go on and on. But what’s the point? Statistics are for losers. Still, he just has to wonder why the bandwagon waited until now — when he is, at 34, the oldest member of the Bears — to roll into his life.

“I guess I had to hit a sportscaster with a pie to get some attention,” says McMichael.

That, of course, is a reference to his postgame show on WMAQ-TV, where McMichael is set loose in front of a live camera. He has been known to wield hunting knives with abandon (usually to stir his coffee or pick his teeth) or crack an egg on the face of his cohost, sportscaster Mark Giangreco; he has made jokes about people’s religious beliefs and sexual preferences and referred to Debra, his 31-year-old blond beauty-queen wife, and her gal pals as “the Kotex Mafia.” He’s just a Texas country boy who likes to get people’s goats.

Usually, he succeeds. The PTA has denounced him, sportswriters and television critics have raked him over in print, and one of WMAQ’s own news anchors has suggested, in polite, ladylike terms, that he take his attitude and shove it where the sun don’t shine — preferably not while he’s on the air, please.

“Yeah, I can rile people up,” McMichael says. “But even when they can’t stand me, they have a hard time taking their eyes off me. You know why?” He lowers his voice, ready to share his secret. “They’re afraid that one day my last brain cell is going to pop and I’m going to go off the edge. And they don’t want to miss it.”

They are an improbable pair, like characters in a modern-day fairy tale: the reigning Beauty and Beast of Chicago. As an athlete, he shines as one of the few bright lights on a low-luster team. As a television personality, he terrorizes the local airwaves, raising audacity and bad taste to an art form. She’s the fizz, a glamour puss whose sweetness is tempered with smarts. She’s his rock; he gave her a gigantic one to prove it.

In person, the McMichaels can’t help but generate a buzz. Their style is Southern gothic: Steve favors flowing silk shirts and pants, Tony Lama cowboy boots, and little John Lennon-style sunglasses; Debra likes clothes that are colorful (aqua, red, orange, or pink) and very detailed (studs, mirrors, or spangles), big earrings, and gold high heels. He’s fond of Kieselstein-Cord belts. She’s got a weakness for what she calls “room-to-grow” jewelry: bracelets and rings with the space to add more diamonds. During the day, he drives a Ford Bronco to Halas Hall and she zips around in a black Cadillac; but at night, they cruise through the city in a red Rolls-Royce.

In the world of pro sports, they are an unusually joined-at-the-hip couple. For the past several years, Debra has followed Steve to Platteville so that they can spend his breaks from training camp together.

She says, “I don’t see why you marry someone and then don’t get to spend all your time with him.”

He says, “I’ll tell you, being around just guys all the time does not motivate me to play football.”

At the moment, their life is like the perfect game, where everything falls into place and they make all the right moves.

He walks into the Channel 5 TV newsroom and clears an enormous amount of phlegm from his throat. This is how Mongo, as he has come to be known, after the Alex Karras character in Blazing Saddles, announces his presence. Then he takes a Bowie hunting knife (a present sent to the station from WLUP radio personality Kevin Matthews) and mumbletypegs it into the top of a producer’s desk.

It is the first night of the new season — both for football and for Sports Sunday, McMichael’s show. The Bears beat Minnesota this afternoon; now a certain level of tension mixed with excitement floats through the air here. What will McMichael do tonight?

She’s a glamour puss whose sweetness is tempered with smarts. She’s his rock; he gave her a gigantic one to prove it.

Given his past performances, it’s hard to say. He has broken a stunt bottle over Mark Giangreco’s impeccably groomed head, squirted him with whipped cream and Champagne, and held him down so that Debra could paint his mouth with lipstick. Sometimes McMichael’s Chihuahua, Pepe, has appeared on the show wearing his own miniature football helmet (painted by Debra) or a red bandanna (sewn by Steve).

Tonight, McMichael is acting frisky, at least as frisky as six feet two inches and 270 pounds of solid Texas beef can be. “Is it OK to say ‘bastard’ on TV after 10:30 p.m.?” he asks. “I’m just checking, ‘cause I know there’s stuff I can’t say. Ever.” He then proceeds to list one obscenity after another. Debra, guileless as ever, puts her hand over her eyes. Giangreco and the producers of the show laugh, albeit a bit nervously. In ten minutes, this man will be sitting in front of a live camera.

“When the show starts, ask me how feel.” McMichael tells Giangreco. And so, minutes later, live in front of their first viewing audience of the season, Giangreco says, “So, how’s it going, Steve?”

“Well, there was a little blood on the toilet paper,” says Mongo, “and I found one of Debra’s Lee Press-On Nails in my underwear.” Giangreco visibly blanches. On the sidelines, the producers reel back and gasp. Debra shakes her head. “I have no control over him,” she says.

And so it goes. Near the end of the show, McMichael pulls out his hunting knife and holds it a few inches away from Giangreco’s throat. Then he squirts him with Silly String. And the show ends.

One minute later, the phone on Giangreco’s desk rings; it is an NBC public-relations man. Giangreco listens for a moment or two, then responds. “Where have you been for the past year?” he asks. “That’s what we do. That’s the show.”

Yes, but what about the knife? says the PR guy. Exactly what image are we trying to convey here?

“Bad taste,” Giangreco shouts into the receiver. “We’re trying to convey bad taste.”

Before McMichael joined Sports Sunday in September 1990, Giangreco had hosted an even-keel show during the football season with Bears defensive tackle Dave Duerson. When the Bears let Duerson go, Debra McMichael encouraged her husband to ask for the job. (“I knew Steve would be good, because he is so funny that you could hire him to do a party,” she says.) He did, but WMAQ-TV was also considering Mike Singletary for the position. In the end, Singletary — a perfectionist — wanted script control, rehearsals, and retakes; McMichael was willing to wing it.

On his first show, McMichael started almost every sentence, “Well, Jesus Christ. . . .” The second week, he made a “fag bar” joke. And on the third program, the phrase “Kotex Mafia” went out over the Chicago airwaves. When this guy said he was willing to wing it, he wasn’t kidding.

Suddenly, the whole city was talking about this loose cannon called McMichael. For years, Channel 2’s Johnny Morris and coach Mike Ditka had owned this time period; in less than a month in 1990, Channel 5 had virtually doubled its own ratings.

For WMAQ, the question became: How do you tone down a man who gives new meaning to the phrase “defying authority,” without losing the edge? For Mongo, the answer was a move away from shock tactics and toward slapstick. (He still retains a fondness for slipping “Kotex Mafia” into his on-air conversation, though. And on recent shows, he has compared his after-game condition to that of a prostitute at a convention — ”I’ve been rode hard and put up wet” — and called his fans “Mongoloids.”)

The results are their own reward: More than 200,000 homes tuned in to watch McMichael’s opening night this fall. And week after week, the ratings show that he and Ditka are virtually in a dead heat to own the time slot. Influencing the weekly outcome are variables such as which show starts later because of run-over games (whoever goes on the air first usually wins the night), cross-referenced with which show cuts first to lower-rung sports coverage, like golf or high-school football (whoever goes junior league first usually suffers a significant loss of viewers).

Also, the results can be major-league headaches. “[McMichael] is one of the least evolved members of the human species,” wrote Sun-Times TV and radio sports columnist Barry Cronin after Sports Sunday’s début this September. “Someday, the audience probably figures, Mongo will actually use that hunting knife he carries around with him to stab Giangreco to death on camera.”

One week later, Sun-Times columnist Richard Roeper started his column by quoting a woman who had called him. “‘I want you to write a column indicting Channel 5 for allowing this Steve McMichael character on the air,'” she told Roeper.

“I don’t think people should still be falling off their chairs over Steve,” says Giangreco. “It’s old news that he might do something shocking. People don’t have to watch. So if they do and then they’re shocked, it’s because they want to be.”

Here’s how McMichael sees it: His job is to get in people’s faces. That’s why he is a defensive tackle. So, sometimes a little of it spills over into the real world. What’s all the fuss? “They advertise Kotex on TV, don’t they?” he says. As for the complaint that he’s often more interested in making a joke or using Giangreco as a punching bag than discussing that day’s plays, he answers, “Football can be so analyzed, can’t it? Oh, boy. ‘What happened on this play?’ Well, it either worked or it didn’t, right?”

For him, it’s simple. Football is not a pretty sport. It’s down and dirty, based on blood, pain, and sweat. You want pretty? Get a baseball player.

Their house in Mundelein is a relaxed, country type of place. (They bought it from Dave Duerson.) They call it their “little lake house,” since their main hacienda is a peach-colored Santa Fe–style spread in Austin, Texas. They live there from February until the middle of the summer. When training camp starts, they pack up their Louis Vuitton suitcases and their six pets (three dogs, three cats) and head back to Mundelein to hunker down for the season.

Although the entire back of the three-bedroom house opens out to a spectacular view of Diamond Lake, there is a cocooning quality to the place. This is where they get away from the world (or used to until the world came to them). The living room is comfortable sofas, Chinese vases, statues of foo dogs, an abstract expressionist painting by Debra, and floor-to-ceiling pink drapes that give everyone’s face a flushed glow.

Down the spiral staircase to the lower level, there is a custom-designed pool table, a Christmas gift from Debra to Steve. Also downstairs is a mirrored weight room, complete with a multistation Universal gym and a suntan bed. They closed up the outdoor swimming pool a few years ago. “If we want to swim, we do it in Austin,” says Steve. For all practical purposes, the white kitchen is closed up, too. “I just hate to cook and do housework,” says Debra.

She likes to go out. He prefers to stay home. They’re crazy about each other, so they compromise: Most times, they go out. Together they have created their own little romantic world. He brings her flowers. She leaves little notes in his wallet. He keeps his hunting knives in her jewelry box.

They have been married for six years (with no plans to have kids); on their fifth anniversary, they renewed their vows in Kona, Hawaii, with Bears kicker Kevin Butler and his wife, Cathy, as their attendants. They tend to finish each other’s sentences, although not always in the way that the original speaker intended. This leads to loopy, cross-referenced conversations, a sort of George and Gracie routine, Southern style.

He thinks their relationship is karma. Meeting Debra changed his whole attitude. “If you’re a match, you watch out for her feelings first before you think of yourself,” he says. “You always put it in the parameters of Well, if I’m gonna do this, how’s it going to affect her?”

She thinks that inside that big macho hulk is a sweet teddy bear. “When I did this beauty pageant, I tripped on my gown one night and I ripped the hem — ”

“Oh, don’t tell this story,” interrupts Steve.

“I’ve got to. See, everyone thinks he’s so mean or crude, whatever — ”

“Oh, Lord.” He settles back on the sofa with an embarrassed air.

“Well, Steve raced out of that hotel, sped down the street, got a speeding ticket — ”

“No, I got out of that.”

She likes to go out. He prefers to stay home. They’re crazy about each other, so they compromise: Most times, they go out.

“You talked your way out, signing a bubble-gum card,” she says. “He got thread and a needle at a store and he came back and hemmed up my evening gown. Because he knew I had to wear it the next night. A three-inch rip on a beaded gown. It took him a couple of hours.”

“Where is that red dress?” Steve asks, all embarrassment suddenly vanished. “Why don’t you show her what a nice hem I put up?”

Debra ducks away, then reappears with a beaded gown that sports a delicately turned, precisely stitched hem. “Now, what other husband would do that?” she asks.

He answers the question himself. “Oh, I was a rare find, yeah, boy.”

Debra tries to explain him. “This is just the way people are in Texas. They’re not having fun unless they’re being loud and rowdy.”

“I’m not loud,” he counters. “I’m just obnoxious.”

“You’re obnoxious and funny.”

He says, “Sometimes I’m not funny, but I’m always obnoxious.” He sighs a sigh of the often misunderstood. “I’m country. And I don’t want to change. I see these buttoned-down, tie-dyed, wind-tunnel-tested boys up here and I think, Oh no, not me, brother.”

So he shocks people. He loves that little jolt of reaction he can produce. It’s become a habit now; he opens his mouth and, within minutes, zap! Somebody’s reeling about something.

He does it because he doesn’t like to be bored. “It’s different, isn’t it? And it’s funny, damn it. I don’t care what anybody says, you laugh at some of my stuff. Now, later, you might think, Jeez, I must be an idiot, laughing like this — ”

Debra says, “You know, you can take the boy out of the country — ”

Steve says, “It’s an act, pure and simple.”

Debra says, “ — but you can’t take the country out of the boy.”

Steve says, “But it must be a good act, because they’re buying it.”

He has his rituals: On a game day, he’s got to wear the same black underwear and the same black socks to the stadium. And he has to walk up and down the field, communing with the hash marks, hours before the playing begins. He hates it when any part of his uniform wears out; he refused to give up his favorite pants, until he was walking around during the Tampa Bay game with a big rip over his butt. Even then, he asked for them to be patched (a new pair, he feared, would bring bad luck), but they were too far gone.

And he can be a rowdy boy. Earlier this year, during a golf tournament at a suburban country club, he got involved in an Animal House–style food fight. “I’m not sure if I started it, but I know I was in it until the end,” he says.

Then there are his public displays with knives. “Sigmund Freud would say that it’s a phallic symbol, wouldn’t he?” he says. He says the knife bit is just a holdover from his country days. Others, including WLUP-AM radio personality Garry Meier, have felt genuinely threatened by McMichael.

“Oh, just ’cause I said I’d cut them,” he says with a laugh. “I think I pulled a gun on Garry Meier, too, didn’t I?” The incident occurred when McMichael ran into Meier at a charity function. Irritated — or pretending to be — about some on-air comments made by Meier and his partner Steve Dahl, McMichael brandished the weapons and said, “You and your fat friend had better stop talking about me.”

“Oh, they were only props,” says McMichael today. “Just a rubber knife and a water gun.” (“Those were real weapons,” says Meier. “And in terms of phallic symbols, McMichael’s gun was just a derringer.”)

He has his opinions. On sports writers in general?

“Cattle. They all follow each other around in little herds, writing the same negative shit over and over.”

Tribune columnist Bernie Lincicome in particular?

“He’d be more interesting if he’d change his style once in a while. He can be funny and insightful, but he’s in such a negative rut.”

The fans?

“They boo a little too fast for my taste.”

The new, sanitized NFL rules?

“Pretty soon they’re going to have us in business suits and ties and whichever team has the best handshake is the winner of the game.”

When he was growing up, back in Freer, Texas, the brightest lights always shone on Friday nights. That’s when high-school football games are played.

“Down there, people live and die that stuff,” McMichael remembers. And his family was no different. His father, E. V., was an oil-field land manager, and his mother, Betty, is an English teacher. He was the second of four kids, “a happy baby who wanted to hug and laugh all the time,” according to his mother. And when he started saying that all he wanted was to play ball (he was seven or eight at the time), his parents said, great — as long as he kept his grades up. They couldn’t wish him a better future. (Richard, his older brother who is now an electrical engineer in Houston, passed on sports. Steve says, “He’s a genius. He got the brains and I got the brawn.”)

When he made the team, his folks were always there for him. And he made every team; in high school, he lettered in football, basketball, baseball, tennis, and track and field. He also played golf. (“He had a little date now and then,” his mother remembers, “but he was such a total athlete that he was too tired to go out much.”) When he played in the All-Star football game, his dad rented a bus and the family’s friends went to Houston to cheer him on.

He was recruited by 75 colleges. Eventually, he passed up a minor-league baseball contract from the St. Louis Cardinals and played football for the University of Texas in Austin, becoming the first Texas boy in 20 years to make All-American three ways: offense, defense, and kicker. (No one in the state has matched him since.)

When he graduated, he was drafted by the New England Patriots. After signing his first pro contract, he bought his mother a new Cadillac — blue, he told her, to match her eyes. He couldn’t help but feel that this was just the beginning.

One year later, the Patriots cut him. Welcome to the NFL.

“I got branded as a troublemaker,” he says. “This was back in my single days. I was a wild boy, out all the time. The Patriots had a veteran defensive line at the time, and I guess they felt I wasn’t going to be dedicated enough.”

Was he a troublemaker?

He shrugs. “If you call not kissing enough ass being a troublemaker, then, yeah.”

The Bears picked him up and, in his own way, he settled down to work. “He is serious about football,” says kicker Kevin Butler. “All the other players respect him because he puts out every game; he performs in a very businesslike manner. Well, as businesslike as a good ol’ boy can be.”

Retired Bear Gary Fencik adds, “Steve and I came to the Bears after being cut from other teams. Seeing the exit door once — that stays with you for your whole career.”

Physically, McMichael is not as big as other defensive tackles in the league; he compensates with sheer determination and extensive weight training. (He can benchpress 525 pounds.) Plus, he’s got the eye and the moves. Which is good, because all he has ever wanted to do is play ball. The sheer pleasure of walking out on the field, of being a player, even the grunt work, all the blood and sweat and snot of football — well, for him, the thrill is never gone.

She used to be a tomboy. Back in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, she liked tree houses, beating up her cousin Phillip, and zipping around on a Honda QA 50 cycle. “Then, I don’t know, I started to change back in high school,” says Debra.

Her father, W. J. Marshall, worked in a steel mill; her mother, Ann, was a nurse. When they got married, Ann was 16 and W. J. was 38. (“Oh, that South,” says Steve.) Debra was the youngest of their five kids, and the feistiest. “I liked to mix it up when I was little,” she admits. (She still does. Recently, a woman spotted the McMichaels in a downtown restaurant. “You are so lucky to be married to him,” the woman told Debra. “No, he’s lucky to be with me,” Debra countered. When the stranger continued, Debra told her companions, “That girl better cut it out or I’m going to have to beat her up.”)

She attended the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, majoring in advertising. Then she decided to see some of the world, so she became a flight attendant for American Airlines and moved to Chicago.

When Steve was a three-year veteran for the Bears, his mother and younger sister came to Chicago to watch him play. “I never saw any women during that visit,” remembers his mother, “and I said to him, ‘Where’s your harem?’ And he said, ‘Momma, I don’t think there’s a decent woman left out there.’ I said, ‘She’s out there, but you won’t find her on a bar stool or in a pool hall.'”

Instead, he found her at O’Hare, when he was putting his family on a plane back to Texas. He asked his sister to get a phone number for that stewardess, the one who made him weak in the knees. Before his sister could, his mother did.

What was it that attracted him to her right away?

“She looked very professional in her outfit, taking tickets,” he says.

Debra stares at him as if she can’t believe her ears. “Is that all you’re going to say?”

“About what?”

“Man, you’re slow talking.”

“Jeez,” he says, “do we have to do this thing fast?”

She snaps her fingers. “Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

“Nobody told me I had to do this interview fast.”

He called her two days later. He already liked it that she was from the South, that she was pretty, and pretty feisty. On their first date, he picked her up in his blue El-dorado and took her to Kelly Mondelli’s, where he had arranged for a table near his picture on the wall. Six months later, they eloped to Las Vegas and got married at the Chapel of the Bells.

Since her marriage, Debra has pursued a modeling career in Texas and Chicago. (Steve’s favorite shot in her portfolio makes her look like a sex-kittenish Ann-Margret.) In 1987, she won the Mrs. Illinois pageant. And this September she began doing her version of Monday-morning quarterbacking with Robert Murphy on WKQX, 101.1 FM.

Although she tends to structure much of her time around her husband, Debra has, in recent years, also worked for Chicago charities. This fall she was on the gala committee for Easter Seals; she is involved with AAIM, the Alliance Against Intoxicated Motorists; and she plans to take on a fund-raiser for the pediatrics ward of the University of Illinois–Chicago Hospital.

She enjoys shopping (“You know how Southern women shop?” asks Steve. “If it’s on sale, you get two”), jogging, painting, and hanging with her girlfriends. Gold-plated members of the Kotex Mafia include Eleanor Mondale, the former Vice-President’s daughter, who was once married to Bears offensive tackle Keith Van Horn, and Rebecca Besser, whose husband, Charlie, owns InterSport, the sports-oriented production company. Cathy Butler considers Debra “one of the most fun and loyal friends you could ask for.”

And she stands by her man. “It gets better for us every year,” she says.

He says, “My best moment was playing in the Super Bowl, but my smartest move was falling for her.”

She says, “I didn’t appreciate the Super Bowl enough. I just thought, Isn’t this great? We’ll be back here every year.”

He says, “Baby, I’m trying.”

Stepping inside Neiman-Marcus, Mongo is distracted by the cosmetics counters. He holds up a display tube of lipstick and says in a falsetto voice, “Oooh, I think this is a good shade for me.” The salesclerks show no signs of recognition. To them, he is just some big galoot in a white silk suit and a Kieselstein-Cord belt who wants to goof on the make-up. They let him.

Upstairs, he is supposed to try on some new Go Silk clothes he’s ordered. But the clothes are in transit, it seems. He flips through the racks; nothing catches his interest.

“What about this, baby?” Debra holds out a brightly colored, highly patterned shirt. “I’d like to see you in this.”

“Yeah, on Halloween.” That’s it for him. “Come on,” he says, holding his hand out to Debra, “I’d rather go find something for you.”

Back on the first floor, they stop at the Chanel accessories boutique, and he picks out a $350 billfold for Debra. “Baby, you need this.” He pays for it and then carries the shopping bag around the store.

Hand in hand, the McMichaels drift over to the Judith Leiber counter, where Steve falls in love with the rhinestone-encrusted evening bags. But Debra’s not quite sure. They move on to hats, then end up back at the Chanel counter, where Steve picks out a pair of cat’s-eye sunglasses for Debra. The damage this time: $250. “I like to spend money on my baby,” he says. He seems serious.

Out on the street, an intense guy with a miniature TV in the palm of his hand falls into step next to McMichael. Although his eyes never seem to leave the TV, the guy recognizes McMichael. “I’m a big fan,” he says, still concentrating on his television.

“What are you watching there, my man’?” McMichael asks.

“The Jetsons.”

McMichael looks at his companions, raises an eyebrow, and silently mouths the words. “The Jetsons!?!!”

“Hey, Mongo, were you in The Super Bowl Shuffle?”

McMichael is startled. Exactly what kind of a time warp is this guy in? “No.”

Never taking his eyes away from The Jetsons, the guy rattles on. “You’re all that’s left.” McMichael is startled again. “They got rid of the punky QB, no more Sweetness and Danimal — ”

McMichael is starting to get a kick out of this nut.

“Yeah, we’re dropping like flies,” he says. “But the NFL just rolls on.”

The McMichaels and the Ditkas are all dressed up — Debra in a black, red, and white harlequin leather jacket, Steve in a brown Go Silk suit, the coach and Diana in complementary shades of bronze and hunter green — but they have nowhere to go. Rather, they are waiting in this WBBM-TV green room for Johnny Morris, Channel 2 sportscaster and former Bear, to arrive. Then they will be able to tape this week’s version of The Mike Ditka Show.

This is the program that airs every Sunday during the season at 11 a.m.; it features Ditka and Morris discussing last week’s game, one member of the team (picked by Ditka), and a fanatically devoted studio audience of fans. It is not to be confused with the Morris-Ditka Sunday sports wrap-up program, which is a direct rival of McMichael’s show with Giangreco at 10:30 p.m.

The walls of this green room are actually green; they throw an eerie, unsettled cast on the faces around the room. Everyone looks a little queasy. Or maybe trapped in a fishbowl.

At times, these days, McMichael can’t help but feel that way. Everything is such a spectacle. What is he? he wonders. A Roman gladiator or a football player?

It doesn’t help that the ESPN crew is here, with a camera in his face again. And across the room, there is this reporter. “Oh, there she goes, writing stuff down,” he says, one hand twirling the ends of his hair, the other holding Debra’s. “You make me nervous with that pen. You’re going to try to make me seem like some kind of nut ’cause I’m twirling my hair.”

No one pays any attention to him. The ladies are talking fashion. And Ditka is watching Wheel of Fortune on a television set. He chews his gum and stares at the screen intensely, as if the answer to world peace — or a sputtering offense — could be found there.

“You know, I heard that Vanna doesn’t always get to pick out the clothes she wears on that show,” says Diana Ditka, nodding at the TV screen.

“Oh, come on. Is that right?” says Debra.

“I heard that she says some of this stuff is not what she would really wear.”

“Well, that must have caused a stir in the fashion world,” says Steve.

“Use Only as Directed,” says Ditka, fiercely.

Everyone turns and stares at the coach. He never breaks his gaze from the set. “Use

Only as Directed,” he says again. He has just solved the Wheel of Fortune puzzle.

Now Diana starts kidding Steve. “Steve, you better watch your language tonight. They’re going to have the beeper out for you.”

“Do you think I can control myself?” he asks with a laugh.

Debra pats his hand. “Stevie’s going to be good,” she says.

He shoots her a look over the top of his glasses. This is news to him.

As Wheel of Fortune ends, Ditka stands and paces around the room a few times. “Well, she talked me into watching that show Coach the other night,” he says, apropos of nothing. Just thinking about it makes him shake his head and snort. “Boy, was that dumb.”

When Morris finally arrives, everyone hustles into the studio. It is packed with pumped-up Bears fanatics: people wearing Bears sweat shirts, jackets, caps that look like a bear’s head. Someone has got a watch or a music box that is cranking out a tinny, slow-speed version of “Bear Down, Chicago Bears.” The energy level is unreal, as if the Super Bowl had just been won in this room — by the Bears, of course.

Ditka, who only moments ago was so remote that he might as well have been on Mars, suddenly seems accessible, even vastly amused by the scene. “Now, ESPN is doing a big special on Steve,” he says, playing up to the audience, “so try to make your questions intelligent.” He pauses. “Then you really won’t get any answers.” Everyone — including the coach himself — cracks up.

The show begins and moves along predictably with film clips, comments, questions. Then it’s time for the guest of the week. When Morris introduces McMichael, the audience goes over the top. He is, at this moment, just as the Bears’ theme song says of the players, the pride and joy of Illinois.

As the applause dies down, McMichael turns in his seat and looks at Morris. “Can I get a sponge for Johnny?” he says, gesturing to Morris’s forehead. “He’s sweating. You don’t have to sweat, Johnny. I’ll be a good boy.”

Morris, grim-faced, spreads his arms apart horizontally, making the universal “cut” motion. “Start the segment over,” he says, looking at his cameraman and producer. Confusion reigns in the studio. “I didn’t like that,” Morris says to McMichael, sternly, like a teacher taking to task a problem child. “I’m not kidding; this isn’t Giangreco’s show.”

A wave of “Ooh”s washes across the audience. For a moment, it’s hard to say where their sympathy — or Ditka’s — lies. “Well, you were sweating,” Ditka says with a shrug.

The segment starts again and this time, when McMichael is introduced, the audience goes nuclear. They’re backing the bad boy. When the screaming and clapping finally fall away, McMichael says, “I think these people like me, Johnny.”

For a while, the show continues without incident. Then a new segment begins with Morris asking McMichael, “Do you enjoy playing more now than a few years ago?”

“Oh, definitely,” he answers. “I know what I’m doing now. You come into the league young, dumb, and full of come — ”

For a few seconds, pandemonium breaks loose. Morris is waving his arms fiercely, stopping the show. Ditka is laughing. McMichael turns his hands palms-upward, feigning innocence. “Is that wrong?” he says. “Start it again,” says Morris.

“C-O-M-E,” spells McMichael.

“Let it stay,” the audience is shouting.

When the segment begins again, Morris skips asking McMichael anything directly; in fact, he will not speak to McMichael for the rest of the show. Instead he throws the interviewing out to the audience. And so it goes until the end.

Afterward, out in the hallways of WBBM-TV, McMichael and Morris cross paths one last time. Morris puts out his hand. Several beats skip by until McMichael shakes it. “I’m sorry I couldn’t use some of that,” Morris says.

McMichael shrugs. “Hey, it’s your show, brother.”

Morris walks away. “Are you upset?” I ask McMichael, who seems subdued.

“Now, why would I be upset?” he asks, in a voice turned up just enough that it might carry. “He’s nothing but an old, washed-up football player.”

“You know, last year Johnny Morris couldn’t get enough of me,” says Steve. It is the next evening and, over a bag of barbecued potato chips, the Morris incident is being rehashed at the McMichael house. “When I held out during training camp? He was calling me at home, wanting me to give him a scoop.”

In the summers of 1989 and 1990, McMichael delayed reporting back to the Bears. He was, through his Texas agent Larry Bales, attempting to renegotiate his contract, but it never worked out.

The holdout was only a partial success, bringing him a small raise. Although McMichael declines to name figures (“More than some, less than others” is all he will say), insiders place his salary from the Bears at $600,000. (Plus about $50,000 from WMAQ.) And while the paychecks of NFL defensive tackles never match those of high-rolling quarterbacks and running backs, this is not an especially staggering salary — especially for someone of McMichael’s stature and consistency.

Does he think he is paid enough?

“I don’t think anyone in this league is paid enough money to do what we do. Which is to risk permanent injury on your body for somebody else’s pleasure. I don’t know. I wouldn’t want to be an owner because I would feel guilty if I was socking all this money in the bank while guys were out there killing themselves.”

He’s played with two broken ribs (he sewed himself a harness), sprained ankles, hyperextended elbows, an arm so bloody that the blood just dripped down and crusted up on his pants leg. He’s had six knee operations, yet he’s never missed a down. But he knows he can’t go on forever.

He’s made good investments (including Scholz Garden, a bar in Austin that he and his agent own); he knows that, after football, he won’t have to work for a living. He is thinking that maybe, when the time comes, he will join the World Wrestling Federation. Honestly. “Me and William Perry, we’d make a hell of a tag team,” he says. All he knows for sure is that life in the real world — that is, life outside of football — scares him.

“Because most people are not worth your time. They’re backstabbing, mudslinging, living-in-glass-houses pieces of slime.”

That’s who is on the outside. On the inside, there are his friends (Butler, Perry, Fencik, actor Jim Belushi), his wife, and those three dogs and three cats that pile up next to him in bed every night.

McMichael and Butler tear through the front door, toss off a couple of hellos, and corkscrew down the spiral staircase. Moments later, the sounds of a cranked-up stereo and racked-up pool balls float upstairs.

It is the day after the team’s first Monday-night game of the season; the Bears, to everyone’s surprise — including, probably, their own — came back to beat the New York Jets in overtime. That road to victory started when, in the last minute and a half, McMichael stripped the ball from Jet’s running back Blair Thomas and then fell on it. It was the third time in that four-week-old season that McMichael had stepped forward with a game on the line after the two-minute warning.

So he’s bone-tired today. And when Debra says that a WMAQ-TV crew will be out for a live interview at 5 p.m., he’s a little cranky. “Boy, you’re throwing me to the jackals of the press, aren’t you?” he says.

Still, he has something he wants to show me. It’s the latest Steve McMichael bubble-gum card. On the front is a full-length photo of him in action, with his name and number 76 across the top; on the back, the card is split in half with a McMichael bio on one side and, on the other, a close-up photo — wait a minute! Isn’t that a picture of former Bear’s tackle Dan Hampton?

McMichael laughs. “After all this time, I’m still shadowed by that man.”

The TV is turned on; he and Butler start to watch the 4:30 news. The lead story is about the Bears’ win. In fact, most of the newscast is about that game. He and Butler throw each other a look. It is news to them that they are such headlines to the rest of the city.

And the TV reports roll on: man-on-the-street comments about the game; people-in-restaurants’ reactions; a nun insisting that God is a Bears fan. And, over and over again, the replays of those last heart-stopping moments, always beginning with McMichael’s big move.

Gradually, as he watches all this, the slightest change registers on McMichael’s face. He has always talked about the world in terms of us and them, inside and outside. But now he has the look of a man catching sight of something new and far away. It’s not quite in focus, but he sees it, nonetheless. He says, “This really is some big deal, isn’t it?”

Comments are closed.