Illinois just can’t keep a governor. In the 21st Century, we’re the only state that hasn’t had one who served two full terms (except Virginia, which limits its chief executive to one at a time). First, George Ryan declined to run for a second term because of the licenses-for-bribes scandal that eventually landed him in prison. Rod Blagojevich was impeached. Pat Quinn fumbled away his shot at a second full term to Bruce Rauner, whose refusal to sign a budget led to his landslide defeat in his own second time around.

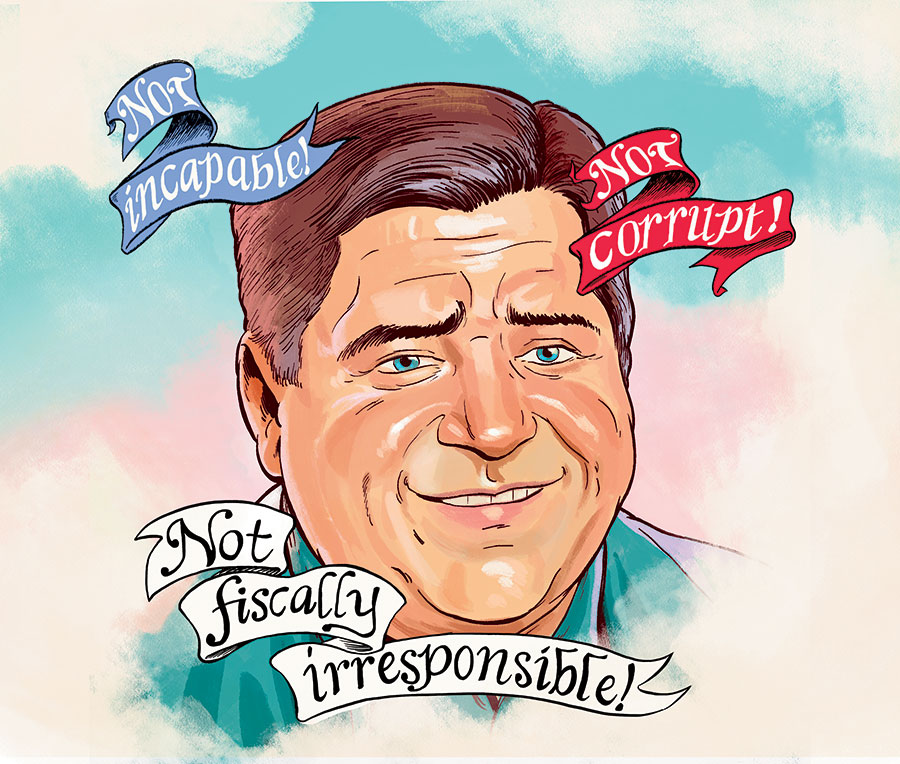

Governor J.B. Pritzker, though, looks ready to break that streak. Unlike most of his recent predecessors, Pritzker is neither corrupt nor incompetent. Those sound like obvious qualifications for a governor, but in modern-day Illinois, they’re almost as rare as unicorn sightings.

“Pritzker can sit there and talk about a record,” says Kent Redfield, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Illinois Springfield. “In other states, that’s what governors are supposed to do; in Illinois, it seems like a miracle. He’s not under indictment. Quinn floundered. Rauner tried to destroy the state.”

In five of the last six elections, the party that doesn’t control the White House has won the governor’s mansion. That trend hasn’t affected Pritzker’s electability. Earlier this year, he polled at more than 50 percent against each of the five Republicans running for that party’s nomination in June: Darren Bailey, Richard Irvin, Gary Rabine, Paul Schimpf, and Jesse Sullivan. “People don’t dislike [Pritzker] as a person,” says Rod McCulloch, whose Victory Research Group conducted the poll. “Being wealthy insulates him from people thinking he’s crooked, like George Ryan trying to steal your money. You really have to attack him on policy. Personal attacks don’t work.”

Pritzker is best known to Illinoisans for his daily press conferences during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the billionaire heir with no prior experience in elective office suddenly grew into the powers of the governorship, shutting down the state’s schools and banning sit-down meals in bars and restaurants. He came across as a calming and decisive leader during a time of fear and upheaval.

His mask mandate will cost him some votes downstate, says Jim Nowlan, a former Republican legislator who lives in Princeton: “The guys in the taverns, they don’t like to be told by Chicagoans how to behave.” In protest, some rural residents posted “Pritzker Sucks” signs in their yards. However, it likely won’t hurt him in the election. The antimaskers’ hero, state senator Darren Bailey of Xenia, who refused to mask up at the Capitol, “would be crucified” if he’s the nominee, winning “an enthusiastic 40 percent of the vote at best,” Nowlan says. Only Aurora mayor Richard Irvin has a chance to appeal to the suburbanites who decide statewide races, Nowlan believes.

Pritzker’s most significant display of competence, though, has been in an area less visible in voters’ daily lives: his management of the state’s finances. Four years ago, when Pritzker was running for his first term, Politico called the Illinois governorship “the worst job in American politics.” Why? Because the state was “on the edge of financial collapse,” with its bonds at near-junk status and its pension system “in worse shape than that of almost any other state.” Illinois, experts say, is more difficult to govern than other states because it must satisfy a large industrial state’s demand for services with the revenue structure of a rural, conservative state: a flat tax, no sales tax on services, and no lucrative signature industry, such as Texas’s oil or New York’s Wall Street.

Pritzker failed in his attempt to eliminate Illinois’s flat tax. However, Illinois has reduced its backlog of unpaid bills to $3.4 billion, down from the $16.7 billion that piled up during Rauner’s budget standoff. The state also added an extra $500 million to its required $10.8 billion in pension payments this year, the first time we’ve overpaid since 2004. As a result of this fiscal responsibility, Illinois received its first bond upgrade in 20 years. The state has benefited from $11.6 billion in federal COVID funds, but has also developed new sources of revenue — legalizing marijuana, expanding gambling, and raising the gas tax.

“It’s a little muddy, just because COVID’s not over, but there are some things we can point to as evidence the state’s righting its fiscal ship,” says Amanda Kass, associate director of the Government Finance Research Center at the University of Illinois Chicago. “It looks like trying to manage the state’s finances and dig the state out of the fiscal crisis is a priority [for Pritzker].”

Trivia question: Who was the last Illinois governor to serve two full terms? Answer: Republican Jim Edgar, from 1991 to 1999. Not coincidentally, Edgar was both honest and competent. He thinks Pritzker is, too. Game recognizes game.

“I think Pritzker has done a pretty good job on the big issues: the budget, the pandemic,” Edgar says, speaking from his vacation home in Arizona. “He got lucky. I wish the federal government had given me billions of dollars.”

Edgar is a betting man — horse racing is his passion — and he’s betting that Pritzker will win a second term, just as he did. “An incumbent governor running in Illinois, if they haven’t really screwed up, they have a good chance,” Edgar says. “The state is in a lot better shape than it was two years ago. It’s a low bar.”

A bar Pritzker’s predecessor couldn’t clear. “Rauner didn’t pay any attention to me,” says Edgar, who tried to talk to the now-ex-governor about the importance of making a budget deal. “He said, ‘The Democrats need a budget more than I do.’ If he had been halfway reasonable on the budget, he’d have been reelected.”

That misstep plays a big factor even now in giving Pritzker an edge for a second term, says state representative Kelly Cassidy, a Democrat from Chicago who helped him pass cannabis legalization and the Reproductive Health Act in 2019. The governor’s case for reelection “starts by following somebody so disastrous, and having people so hungry for competence, and delivering on that competence.”

“I’m capable of doing my job” is not a scintillating slogan, but after 20 years of Ryan, Blagojevich, Quinn, and Rauner, it may be all Illinois voters need to hear.