Lesley Williams is ticked off. The ire of the longtime Evanston resident and community activist is aimed at a rich and powerful neighbor: Northwestern University. She is part of a growing residential and political coalition challenging what it calls the boldest and potentially most disruptive university-led initiative ever imposed on the suburb.

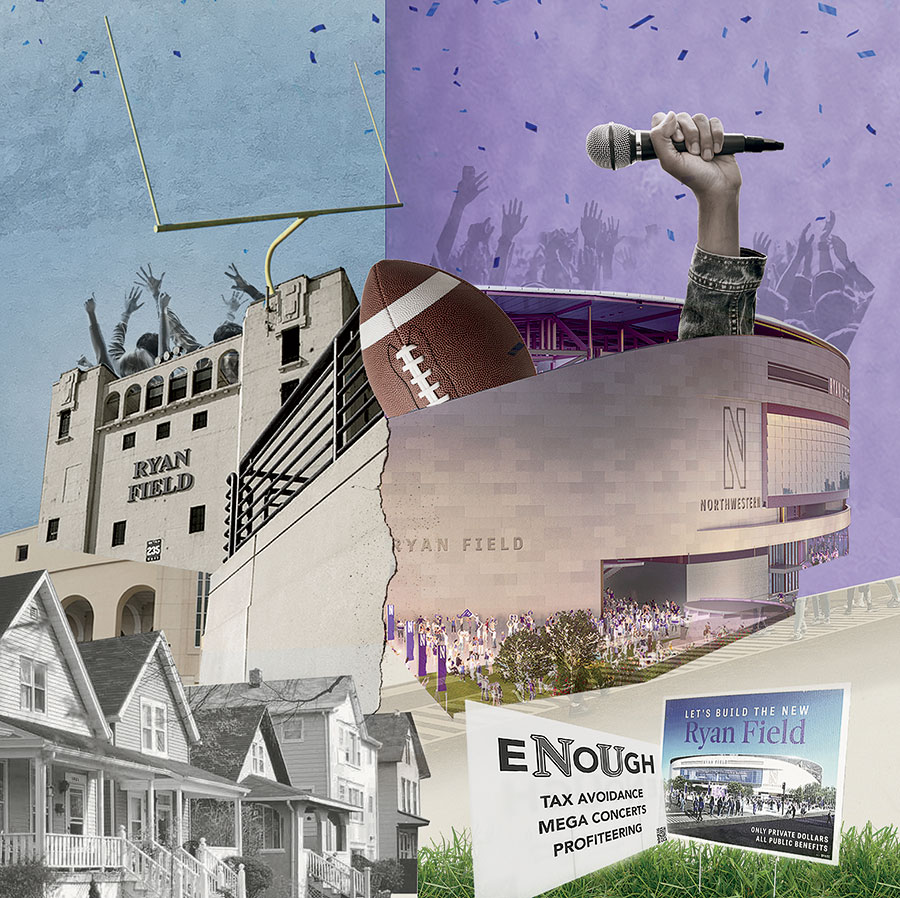

Northwestern is proposing an $800 million plan to demolish the aging Gothic-style Ryan Field, the football stadium a couple of miles west of its lakefront campus. The site would be reconstituted into a 35,000-person sports and entertainment complex that would be in a class with other elite university facilities and could host more than the current half-dozen or so football games each autumn.

But to build its field of dreams — detractors call it a “field of schemes” — Northwestern needs the Evanston City Council to sign off on a zoning change and special uses of the stadium: The school wants it to host at least 10 concerts or other major events annually, along with smaller gatherings. Northwestern argues these are essential to financially sustaining the new facility while generating jobs and, by its estimate, $1.3 billion in economic impact for Cook and Lake Counties by 2031.

It’s a huge ask, one that raises passionate questions about Evanston’s relationship with Northwestern, which, as a nonprofit institution, is exempt from property taxes. “Not contributing to the city, which is capable of making this lucrative venture possible for Northwestern, makes people very angry,” says Williams, president of the Community Alliance for Better Government, a local group that represents hundreds of Evanston residents and business owners and even some university employees and students.

Those who live near Ryan Field already contend with the traffic, noise, and rowdiness accompanying Wildcats football, and many fear the toll of adding more heavily attended events. Nearby Wilmette, too, frets about a revamped stadium becoming “one of the largest outdoor concert venues in Illinois,” as its village manager, Michael Braiman, wrote in an email to Chicago. It would seat more than both the United Center (23,500 seats) and Allstate Arena (18,500). Those venues have ample adjacent parking lots, something the Ryan plan still has to work out. (To supplement its lots for football games, the school relies on the nearby public golf course and Evanstonians renting out their driveways.) “We’re pushing back hard,” says David DeCarlo, an attorney and cofounder of the Most Livable City Association, a nonprofit started by residents opposed to the rebuild. “Concerts are a nonstarter.”

Evanston and Northwestern were both founded in the mid-19th century and are inextricably linked, but their relationship hasn’t always been easy.

The issue has sparked a conversation about whether the university is paying its fair share to Evanston. Community groups — and some city leaders — want Northwestern, which has a $14.5 billion endowment, to contribute “payments in lieu of taxes” for police, fire, and other public services the university enjoys. Some schools already do that: Yale agreed in 2021 to contribute $135 million over six years to New Haven, Connecticut. “This discussion is so long overdue,” says Clare Kelly, a council member who chairs the Northwestern University–City Committee.

One high-ranking city official, who did not want to be identified, says Northwestern is firmly against payments in lieu of taxes, as well as community benefits agreements, or CBAs, guaranteeing minority and women employees and contractors. But when asked about these possibilities, the school doesn’t publicly slam the door. “We have continually engaged with community members throughout this process, and we have no plans to stop,” the university said in a written response to Chicago.

The school points out that the sports and entertainment complex will cost taxpayers nothing (local insurance magnate Patrick Ryan and his wife, Shirley — Northwestern alums and longtime benefactors — pledged $480 million toward it and other programs) and that Evanston stands to gain $659 million in economic impact during construction alone, from the hiring of local contractors, vendors, and workers. It also points out that the facility’s design will address noise, lighting, and other environmental concerns and that its capacity is actually shrinking, from 47,000 seats, to make room for amenities like premium boxes.

Late last year, Northwestern rolled out its Ryan Field: A New Vision initiative with a marketing campaign worthy of its prestigious Kellogg School of Management. In addition to the results of a school-funded survey showing that about 60 percent of residents favored the rebuild, the campaign included testimonials, some from leaders of Evanston’s minority communities. The effort is being supplemented with supportive yard signs, sprouting up in the stadium’s neighborhood and beyond. Proponents contend that the revamped site will boost Evanston businesses and thus the local tax base. “It will be a game-changer for Evanston to have a state-of-the-art facility right here,” says Gina Speckman, executive director of Chicago’s North Shore Convention & Visitors Bureau, in her video endorsement on the Facebook page Fans of Ryan Field.

Evanston and Northwestern were both founded in the mid-19th century and are inextricably linked, but their relationship hasn’t always been easy. Periodically, there are flare-ups, usually when the school acquires property and removes it from the city tax rolls. This time, activists argue, Evanston has more leverage because the project is reliant on a zoning change. Yet some civic observers worry the City Council, which has been mostly mum on the plan, will rubber-stamp the school’s blueprint. “The longer everyone stays neutral, the more it emboldens Northwestern,” says community organizer DeCarlo. “Isn’t it the role of the city to question the university?”

That message appears to be resonating in City Hall. Evanston is hiring an independent research firm to map out the full impact of Northwestern’s plan. The city staff is studying the effects on traffic, neighborhoods, and lifestyle. “There’s a lot to analyze. Plenty of questions, concerns, and the potential upsides,” says Evanston’s mayor, Daniel Biss.

Meanwhile, both civic activists and Northwestern are expected to jawbone and lobby the 10-member City Council for their agendas. The school wants to begin construction late this year, but it will have to endure a long, hot summer of intense, even angry, negotiations before that game plan can be executed.