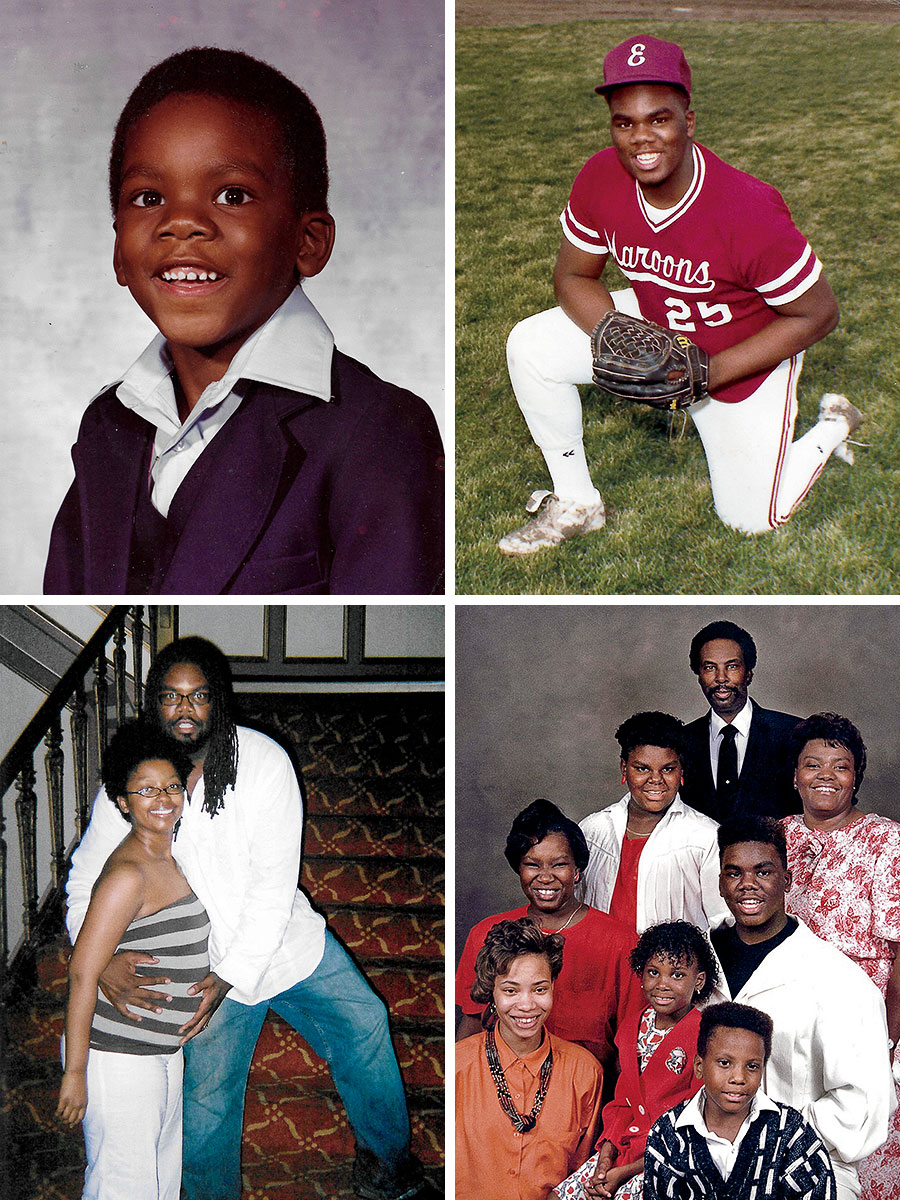

Long before Brandon Johnson ever thought of running for office, or even of moving to Chicago, his classmates at Ellis Middle School in Elgin called him “Mr. Mayor.” He was always the most serious young man in the room. At Ellis, he was the eighth-grade class president. In high school, he carried a briefcase. He wore a tie. He had, says his sister Andrea Johnson-Williams, “a presence.” His father, Andrew, was a pastor in the Church of God in Christ, the largest Pentecostal denomination in the United States. His congregation had 300 souls, and it was expected that one day Brandon would take over his pulpit. He was the sixth of 10 children, but his maturity and sense of purpose marked him as the heir.

When he was 19, after his freshman year of college, his mother died of health issues stemming from her congestive heart failure, and he took charge of the church’s Tuesday night youth group. He drove a 15-passenger van to pick up kids from the poor side of Elgin, east of the Fox River, then fed them dinner and counseled them on dating and bullying. “Brandon was always at the core of setting values, especially for the young ladies: ‘You deserve a certain level of treatment,’ ” recalls his sister. “That wasn’t necessarily keeping your chastity, but if you do make that decision, here’s what qualities you should be looking for.”

Johnson understood the teenagers’ plight because he’d also grown up on the poor side of Elgin, a satellite city of Chicago that by the 1990s was so far past its industrial and commercial heyday that the state tried to rescue it with a riverboat casino. Preaching was his father’s calling, but preaching wouldn’t feed 10 kids, so Andrew Johnson Jr. supported his family with odd jobs: driving a truck, rehabbing houses. After he injured his back in a semitruck rollover, he was unable to find full-time work, so he sold shoes part-time at Sears. One Christmas, he bought his children toys from the returns department. (Brandon got a G.I. Joe.) Brandon’s mother, Wilma Jean, styled hair in the house. Some weeks, the family had no water because the bill had gone unpaid. Other weeks, no electricity, requiring them to run an extension cord to a neighbor’s house. There were three bedrooms — one for the boys, one for the girls, one for the parents — and one bathroom, for all 12 Johnsons, plus whatever foster children, cousins, and battered women were living in the house at the time. The family’s finances finally stabilized when Andrew landed a state job at the Elgin Mental Health Center, caring for patients on the night shift.

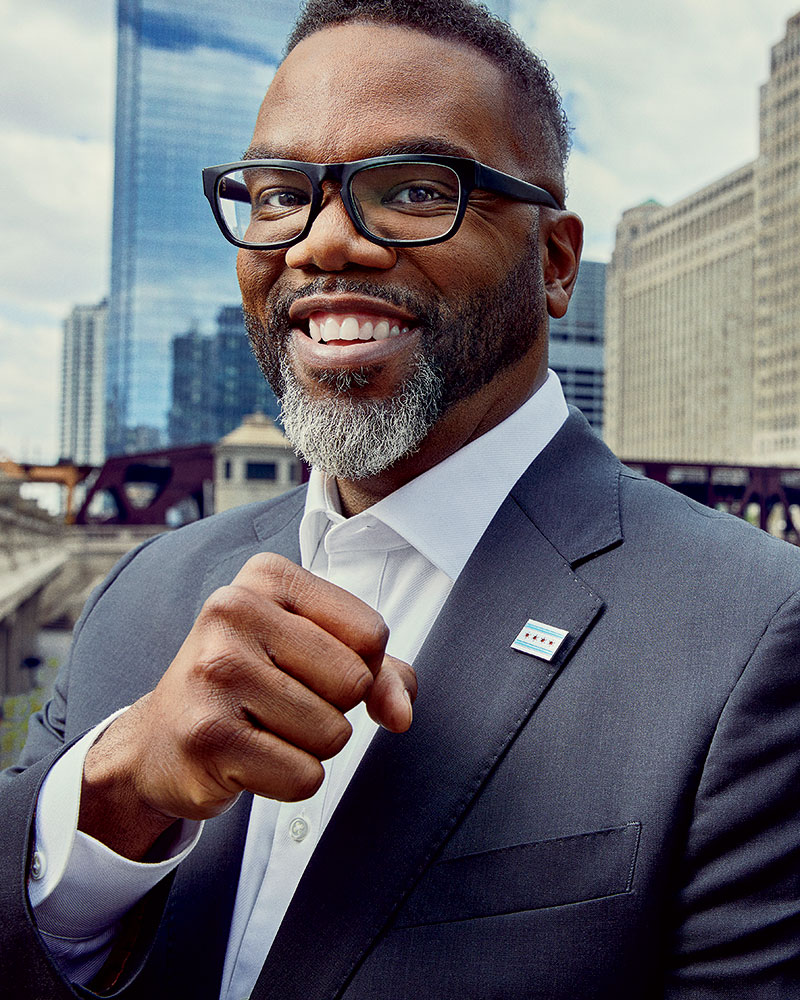

There are many unknowns about how Brandon Johnson will govern Chicago, but one thing is certain: The city has never had a mayor like this. “Here’s what I take to the fifth floor,” says Johnson, 47. “I understand the conditions of the working poor. There are people who go to work every single day and, in many instances, like my father, have multiple jobs. There are real examples of people who go to work every single day, and they are still struggling to make ends meet every single day. Just because someone is struggling, it doesn’t mean they’re not doing their part to have a better, stronger, more thriving lifestyle. There are conditions and circumstances that surround families that oftentimes get ignored.”

Brandon Johnson is the most progressive leader in Chicago’s history, promising revolutionary approaches to taxation, education, social welfare, and policing. Among other things, he has vowed to “make the ultra-rich pay their fair share,” steer at-risk youths to jobs rather than violence, reduce homelessness, and implement the doctrine of “treatment not trauma” — that is, social workers, rather than police, responding to mental health 911 calls. The former public school teacher is, of course, a product of the Chicago Teachers Union and the city’s tradition of community organizing — a movement that has long sought to hold power accountable but has never held a power seat itself. For the public employee unions, the community activists, the socialist publications such as Jacobin and In These Times, Johnson is the fulfillment of decades of railing against the establishment.

Here’s what I take to the fifth floor,” says Johnson. “I understand the conditions of the working poor.”

“We’re in uncharted territory here,” says Jacobin editor Micah Uetricht, author of Strike for America: Chicago Teachers Against Austerity, a book about the 2012 CTU strike. “I am unaware of any rank-and-file activist from a union being elevated because of strikes and other organizing to the mayoralty of a major American city. There have been people who have been champions of a working-class agenda, but never someone who comes directly from that movement.”

The stakes are high, and not just for the progressive movement in Chicago. If Johnson succeeds, his mayoralty could become a model for left-labor alliances to take over city halls elsewhere. If he fails, Chicago could return to the neoliberal governance Johnson built his career fighting against. At the same time, Johnson will have to balance the demands of the left-wing activists who backed his candidacy with his election night promise to the hundreds of thousands of “Chicagoans who did not vote for me” to “be the man for you, too” — a needle his more moderate predecessors have not needed to thread.

But to understand what type of mayor Brandon Johnson will be, you have to understand where he came from, how he got to the mayor’s office … and who got him there.

Every morning at 5:30, Brandon Johnson’s family would wake for prayers. They hosted Bible study at the house. Went to church twice a week. Traveled to other churches for gospel music competitions. Johnson met his wife, Stacie, at a religious convention. The couple married when they were 22.

Throughout college, Johnson continued to lead his church’s youth group and, he says, “just assumed that eventually I would take more of a ministerial sort of role.” He got into politics almost by accident. He worked as a YMCA youth director while studying for a master’s in teaching at Aurora University, but he lost his job to cutbacks. He and Stacie were living in Oak Park at the time, so he went to see his newly elected state senator, Don Harmon, to ask him about “his commitment to social services and programs that support young people,” he recalls. Johnson wound up getting hired to do the legislator’s community outreach.

“His district director at the time pretty much said, ‘Look, no one comes to visit a politician who doesn’t have a job who doesn’t ask for one,’ ” Johnson says. “They were more impressed by that. But I wasn’t there to ask for a job. I was really into making sure that resources at the state level would be invested in programs that serve young people.”

After a year with Harmon, Johnson went to work as a legislative aide for state representative Deborah Graham, who represented Oak Park and the Chicago neighborhood of Austin. He was quickly promoted to chief of staff in Graham’s district office. The job paid less than $30,000 a year, but it introduced Johnson to the practical ways in which government serves the needy: He helped mothers visit their sons in prison, enrolled poor families in the food stamp program, directed the mentally ill to hospitals, and found educational supplies for homeless students.

The job also immersed him in Austin. In 2004, he and his wife moved to the West Side neighborhood, eventually buying an ample frame house on a motley block near the border with Oak Park. Austin became Johnson’s new community — and the place where, as Graham puts it, “he began learning the issues.”

On the West Side, Johnson also found a religious home: Lawndale Christian Community Church. To follow a social gospel that “we ought to care for the most marginalized, those who have been most oppressed,” says its pastor, Jonathan Brooks, the church operates a health clinic for the uninsured and a legal clinic for young people facing prison. Johnson has led 6:30 a.m. Bible studies at Hope House, the church’s ministry for people with addictions. He also helped finance a church-sponsored barbershop, where he goes to maintain his pyramidal hairdo.

But preaching was not his calling. Nor was legislative work the career Johnson had studied for, and it didn’t pay well. So he turned to teaching. Johnson had worked at the New City YMCA, just north of Cabrini-Green Homes. It was, he says, “a place that really embraced my leadership.” In 2007, motivated by a desire to help children reach their dreams, Johnson applied for a job at Jenner Elementary Academy of the Arts, which served the public housing project.

At Johnson’s interview, the principal was skeptical of the young man, then with dreadlocks, who had never stood in front of a classroom before. He was applying to be the seventh-grade social studies teacher in room 309, which was notorious for driving away even more experienced educators. “The principal was kind of giving him a hard time,” recalls Tara Stamps, a teacher who’d met Johnson when he worked at the YMCA and became his mentor at Jenner. “A few questions in, they were kind of raking him over the coals. It was way more tense than it needed to be.” Stamps helped convince the administration that the school, which only had only three men on its faculty, needed “a Black man who’s married and loves his wife and has been through the experience of being a poor Black boy” as a role model for the male students.

During Johnson’s time at Jenner, the Chicago Housing Authority was demolishing Cabrini-Green, resulting in the scattering of the Near North Side’s Black population. While teaching a unit on South Africa, Johnson talked about the apartheid system’s “political decisions that criminalize Blackness” and “lack of investment, particularly around housing.” His students could relate.

Johnson always taught in a suit. He addressed his pupils as “Mr.” and “Miss.” Knowing his room’s history, though, he told his students, “You’re not going to walk over me.” As a rare male teacher, he was recruited to coach basketball, softball, and flag football. The boys were enthralled by Mr. Johnson’s professional wardrobe, so he gave them ties of his own, and they decided to wear shirts and ties on game days.

After three years at Jenner, Johnson transferred to Westinghouse College Prep, a selective enrollment high school in East Garfield Park, where he taught history. He had been at Westinghouse less than a year when he applied for a position as an organizer at the Chicago Teachers Union. It was, he says, a reaction to the disparity in resources he had seen between Jenner and Westinghouse — a gap that was apparent even to his students. During his mayoral campaign, Johnson often told a story from his time at Jenner to make this point: One day, as he struggled to keep control of his class, a student told him, “Mr. Johnson, you know what the problem is? The problem is, you should be teaching at a good school.”

Says Johnson: “Having taught in a neighborhood school and a selective enrollment school, it really highlighted the stratification that exists where there are students who are capable and bright and could have more fulfillment if those schools were invested in. I wanted to be a part of a larger responsibility to make sure that every single child had access to a fully funded school.”

This meant leaving the classroom. The same year Johnson joined the staff of the CTU, Rahm Emanuel was elected mayor. Teachers saw Emanuel as a neoliberal privatizer, and the union was in constant conflict with him — over the heatedly negotiated 2012 contract, which led to a seven-day strike; over the closing of 50 schools on the South and West Sides (“one of the greatest political destructive acts ever done,” Johnson says); over the establishment of charter schools. Those fights with the mayor radicalized the union, motivating it to seek power to protect its interests. Johnson was a member of the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators, or CORE, a militant faction of teachers that took over the CTU leadership and led it in a more confrontational, political direction.

Just a few years later, one of their own would win control of the city’s most powerful office.

At Johnson’s election night party, at the Marriott Marquis on the Near South Side, DJ Slugo led the crowd in the “Cha-Cha Slide” — and neatly summed up the historical import of the former teacher’s victory. “Harold Washington’s turning over right now,” he crowed into the mic. “Chicago’s got a new supermayor.”

Before taking the stage to give his victory speech, Johnson was introduced by the CTU’s firebrand president, Stacy Davis Gates, who proclaimed his election the fulfillment of a decade-long struggle. “Karen Lewis said that we were going to take our grievances to the voters of Chicago because they didn’t listen at the negotiating table,” Davis told the crowd, referring to the Emanuel administration. “She said they didn’t listen when we marched across the city. They didn’t listen when we had a hunger strike. They didn’t listen when we barricaded ourselves. They did not listen, but Chicago tonight …” Her emphasis punctuated the thought without her having to complete it.

And so, though it seemed like Johnson came out of nowhere, his election was a long time in the works. He himself had played a significant role in the struggle of which Davis spoke. As a CTU staff member, the former legislative aide was called on to lobby Springfield for an elected school board. He was sent to the City Council to stop charter schools. He took on the grunt work of organizing: During the 2012 teachers’ strike, he worked the phones, led picket lines, and organized rallies. In 2015, he involved himself in the bitterest of all school closing battles, over Walter H. Dyett High School in Washington Park. Parents and community organizers conducted a hunger strike to try to save the neighborhood school. Johnson and two colleagues joined on day 24. (Even before that, he had helped members of the Kenwood-Oakland Community Organization block off an elevator at City Hall with a “Save Dyett” sign.) During the day, Johnson and the other strikers camped out in front of Dyett; at night, they slept in the offices of Operation PUSH. Johnson recalls that he was “incredibly sleepy” and relied on “adrenaline” to get by without food. After 34 days, the school district compromised, agreeing to keep Dyett open but as an arts academy.

“Our ability to do our work as educators had become politicized, not by us, but by mayors and governors,” says Jesse Sharkey, vice president of the union at the time. “We really felt like our job among the union was to figure out how to build power in order to make the lives of our students better. I don’t think that Brandon wins without a movement.”

In that way, Mayor Emanuel begot Mayor Johnson. “Me becoming mayor of the city of Chicago, there is certainly a direct tie to the fight for public education,” Johnson says. The school closings were “a political attack against the working people, particularly Black and brown people,” he says. “So you had a major political player nationally strike one of the greatest blows to the civil rights movement.”

In 2014, the CTU helped found United Working Families, the political organization that would eventually conduct most of the ground game for Johnson’s mayoral campaign. That year, Johnson told Jacobin that “if elected officials are not responding to the needs of the community in a real way,” then United Working Families could “train candidates to take on incumbents around the issues that have been built through our local organizing.” That included the biggest incumbent. The CTU’s president, Karen Lewis, planned to run against Emanuel in 2015, but then learned she had brain cancer. (She died in 2021.)

An avowed progressive who worked as an organizer for the Chicago Teachers Union, Johnson says his decision to run for mayor was “based on my belief system, it was based upon a movement, and it was based on the city of Chicago needing someone to unite people.”

Johnson made his own bid at elected office when he ran for the Cook County Board in 2018, against incumbent Richard Boykin. His campaign had the support of board president Toni Preckwinkle, who was angry that Boykin had voted to overturn her sweetened beverage tax. She put out a mailer for Johnson, who won by a mere 437 votes. Though Preckwinkle may have supported Johnson in part because he wasn’t Boykin, she also, she says, appreciated the fact that he was a teacher — “not just a teacher, but a history teacher, God bless him,” just as she had been before joining the Chicago City Council. Teaching, she says, is good preparation for politics because “you have lots of different constituencies, not just the people in your classroom, but their parents, the faculty and staff at the school, the community.”

Once Johnson joined the board, Preckwinkle took him under her wing, tapping him to oversee the passage of the Just Housing Amendment, which prohibits housing discrimination against those with criminal records. Johnson also sponsored the Justice for Black Lives resolution, calling for investments in mental health, job creation, housing, restorative justice, and violence prevention, and helped secure $75 million in violence prevention funding for neighborhood groups. (Throughout his term on the county board, Johnson continued working as a CTU lobbyist — a gig that came with a salary of between $83,000 and $103,000, potentially higher than his $85,000 board compensation. Because CTU isn’t registered to lobby Cook County, the county’s ethics code didn’t prohibit Johnson from holding both positions.)

In the summer of 2022, CTU officials were thinking about who they could back as a candidate for mayor when Johnson approached them, Sharkey recalls: “He said, ‘I think I could do this.’ He saw a path.” Sharkey was convinced of Johnson’s political potential, not just because of his lobbying work but because of a speech he gave at the American Federation of Teachers convention in Pittsburgh in 2018. “It was masterful. He was so compelling,” Sharkey says. “It was an Obama moment.”

But despite his policy wins as a county commissioner, Johnson was not running from a high-profile position. Most Chicagoans can’t name their county board representative. Remembering her own failed bid for mayor in 2019, Preckwinkle advised Johnson to “armor up.” He didn’t have the celebrity of Jesús “Chuy” García, the longtime politician who forced Emanuel into a runoff in 2015. Nor did he have the money of Paul Vallas, the candidate of the city’s business and financial establishment. What he did have behind him was a movement.

In October, the CTU board brought Johnson’s name to the union’s House of Delegates, which voted to endorse him if he ran. And while his seeking the fifth floor of City Hall might have seemed like a big jump, Johnson doesn’t see it that way. “It wasn’t, ‘Oh, that’s too far.’ That’s not how I looked at it,” he says. “The impetus was not based upon what my legislative or electoral experiences were. Really, it was based on my belief system, it was based upon a movement, and it was based on the city of Chicago needing someone to unite people.”

It helped that Johnson stood out from the other eight candidates in his professional polish, his devotion to a progressive agenda, and his ability to communicate a vision for the city’s future — the product of being a preacher’s kid. (Another product: “I’ve never heard the guy curse,” says Sharkey. “When Brandon is really upset about something, he’ll say ‘freaking freaks.’ ”)

Stacy Davis Gates made him,” a longtime Chicago political journalist says. “Stacy Davis Gates owns him.”

But he was not merely a charismatic politician with a left-wing platform. With the endorsement of the Chicago Teachers Union came the resources of United Working Families — essentially the union’s political arm, as it’s chaired by Stacy Davis Gates. Casey Sweeney, a CTU staffer, was loaned to United Working Families to help direct Johnson’s field campaign under executive director Emma Tai. Chicago is the birthplace of community organizing, and Johnson applied those principles more than any mayoral campaign ever has.

In early mayoral polls, his support was in the single digits, but he made himself ubiquitous at meet-and-greet house parties and knocked on doors himself. During the runoff, Vallas outspent him nearly two to one. (The CTU contributed more than $2 million to Johnson’s campaign.) But Johnson’s team won the ground war: In all, his volunteers made 1.3 million phone calls, knocked on 555,000 doors, and sent two million text messages. That intensity gap was evident in the way the candidates presented themselves as well. Johnson was a smoother, more flesh-pressing campaigner than the wonky Vallas, who seemed most comfortable quoting statistics. During a North Side swing on the Saturday before the election, Johnson scarfed down samosas on Devon Avenue and fried chicken on Argyle Street, then inspected CTU T-shirts at the Andersonville shop Raygun.

“What size is this?” the husky Johnson asked. “We need an extra-large. We have to figure out a hoodie design. That’s really my thing.”

At the Andersonville bookstore Women & Children First, Johnson marveled at a “Brandon Is Better” poster bearing his caricature — a reminder that he had gone from obscurity to household name in a matter of weeks. “I’m still getting used to seeing my face drawn,” he murmured.

On Election Day, Vallas did a radio interview with WLS, then took the afternoon off. Johnson raced around the city to polling places in East Garfield Park, Belmont Cragin, Wicker Park, Avondale, and Rogers Park. He hugged his volunteers. At the very last stop of the campaign, at Willye B. White Park on Howard Street, a person who appeared to be homeless recognized the candidate. “Is that Brandon Johnson?” she asked. “I want to meet him!” The woman pushed through the crowd to get at Johnson, who eagerly shook her hand.

It is the essence of the progressive outlook that the man is never as important as the movement. As mayor, Johnson will no longer be a member of the CTU, but he won’t soon forget that he got there because of the teachers — and he won’t stay there without them. After Lori Lightfoot was elected in 2019, it was said her support was “a mile wide and an inch deep.” Johnson’s support is deep, but it originated from a single well.

What’s still unclear is how much sway the union will hold over the office. At Johnson’s victory party in April, a Chicago Public Schools teacher at the event said he was thrilled because “we won’t have to go on strike next year” — meaning he expects Johnson to give the teachers the contract they want when the current one is up. After all, despite Johnson’s insistence that he’ll approach it like any other city contract, it’s hard to argue that the CTU influence won’t be felt on both sides of the negotiating table. “Stacy Davis Gates made him,” a longtime Chicago political journalist says. “Stacy Davis Gates owns him.”

Johnson has closer ties to Chicago Public Schools than any mayor in modern memory. Unlike Lori Lightfoot or Rahm Emanuel or the Daleys or Harold Washington (who had no children), he sends his kids to public schools. His 15-year-old son, Owen, who plays the violin, attends Kenwood Academy High School, which is known for its music program. His 10-year-old son, Ethan, and his 8-year-old daughter, Braedyn, go to Ole A. Thorp Scholastic Academy in Portage Park. Johnson will have less control of the schools than his predecessors did, as the transition of power to an elected school board begins during his term. But he is determined to prevent further school closings, even after the moratorium on that ends in 2025. (He has suggested that underenrolled schools could share space with childcare facilities and health clinics.) And he will work with Springfield to see that CPS gets the full benefit of a 2017 state law that funds schools based not just on enrollment but on their needs, such as providing resources for students from low-income households or for those who do not speak English.

Of course, education won’t be the only item on Johnson’s agenda. One reason his campaign produced so much excitement, and attracted so many volunteers, is that his followers saw him as standing up for “poor and working people,” in the words of Jonathan Nagy, a 33-year-old queer artist from Logan Square who canvassed and designed posters for Johnson’s campaign. To avoid raising property taxes, the new mayor wants to reinstate the corporate head tax, tax airplane fuel, and impose a “mansion tax” on property sales over $1 million. He also wanted to tax financial transactions, but Governor J.B. Pritzker nixed that, saying it would chase traders out of the city.

I find it to be harmful to disparage young people and families and lump people as violent and criminal,” Johnson says. “Is that a fair characterization of Black children?”

Likewise, Preckwinkle says Johnson will have to forgo fulfilling his loftiest progressive dreams until he can solve the city’s most pressing issues. “The labor people and the community activists who supported him have to give him grace to do the two things that he absolutely has to do, one of which is to get a handle on the violence, and the other is to address the financial crisis,” she says, alluding to the underfunded pension system and persistent budget deficits. “When I ran in 2019, those were critical issues. And the situation is only worse now. That means that it’ll be hard for him to move a broad social justice agenda, given the fact that those are the two things that he has to deal with right now.”

Johnson, however, does not see a distinction between social justice, fiscal responsibility, and public safety — those goals, he argues, can be achieved by creating a more just society. “I personally believe that the financial responsibility of government is to make sure that we are guaranteeing economic security,” he says. “That’s how you protect neighborhoods. So my approach is going to be getting our fiscal house stabilized while making investments that ultimately create security in our neighborhoods.”

Perhaps most controversially, Johnson has backed alternative strategies for reducing crime — namely, to focus on addressing its root causes. On the campaign trail, he pledged to assign mental health professionals to respond to certain 911 calls and proposed doubling the number of teenagers hired by the city’s summer employment program as a way to keep them out of trouble.

Though a majority of voters showed their support for this approach by electing Johnson, their steadfastness — and his — was tested for the first time before he even became mayor. After the mid-April incident in the Loop in which a large group of teenagers created chaos, smashing car windows and attacking tourists, Johnson released a statement that condemned the disorder but also added a significant “however”: “It is not constructive to demonize youth who have otherwise been starved of opportunities in their own communities.” The next day, the Tribune, which had endorsed Vallas, posted an editorial calling the statement “progressive propaganda” and asserting that it “likely has already cost the city real money that Johnson is going to have to replace with higher fees and taxes” because it would scare away visitors.

When Chicago interviewed him that afternoon, backlash to his response was growing — but Johnson claimed to be unaware of it. His busy mayor-elect schedule, he said, had kept him away from Twitter. “We don’t condone the activity that was obviously reckless and irresponsible,” Johnson clarified in that interview before doubling down. “What I’m saying, though, is I find it to be harmful to disparage young people and families and lump people as violent and criminal. Is that a fair characterization of Black children? That Black children are violent and that they don’t have parents?”

Investment in programs to divert young people from gang life has worked in New York and Los Angeles, whose murder rates have diverged from Chicago’s since the millennium, says Roseanna Ander, founding executive director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab. Johnson’s anti-violence proposals, she argues, have recognized that “public safety is something that requires many parts of government and society to be working together” — not just the police and the criminal justice system.

But addressing the root causes of crime also requires patience. It can take years to pay dividends. Johnson’s predecessor was turned out of office in part because murders increased 50 percent on her watch. If crime continues to spike, Johnson’s policies will inevitably be blamed.

When Chicago was awarded the 2024 Democratic National Convention a week after Johnson’s election, Republicans snarked that delegates would have to find room in their suitcases for bulletproof vests. (Johnson calls that comment “racist” and “disparaging of a major city.”) Johnson attended the Shedd Aquarium press conference announcing the selection. He stood behind Mayor Lightfoot and compared his role in landing the convention to Steve Kerr’s in winning a Bulls championship in 1997 — he’s getting the last shot. The convention will take place in a city governed by a progressive mayor of color, an image the Democrats want to claim for the party. It will be Johnson’s first opportunity to show the nation the “better, stronger, safer city” he has promised Chicagoans. He just has to deliver.

No matter how humble your origins, it is not easy to remain a man of the people as the mayor of a city of 2.7 million people. Johnson does not live in a lavish house — he bought his four-bedroom, two-bathroom home for $150,000, and its white paint is peeling. But now there is a police SUV posted out front.

A week and a half after his election, he visited the Muslim Community Center on Elston Avenue for an iftar, the fast-breaking meal eaten after sunset during Ramadan. Johnson had attended Friday prayers there during the campaign and was keeping a promise to return if he won. (Both Johnson and Vallas courted Muslim and Asian American voters, previously marginal constituencies that became important in this close election.) A pair of black Ford Expeditions pulled up to the curb, and a member of Johnson’s advance team opened the door. The mayor-elect stepped out and examined his reflection in one of the SUV’s smoked windows. He smoothed his hair. He adjusted his burgundy polka-dot tie. A uniformed guard led Johnson through a back door, and he was seated near the dais; on the table were paper plates with dates, a traditional way to break the fast. Johnson bowed his head during the Arabic prayer, then made a short speech about his own religious upbringing.

“When we would sacrifice ourselves, for the benefit of others, it is the greatest act that we can ever display,” Johnson said, in that deliberate public speaking cadence he learned in church. “If we’re going to be a better, stronger, safer Chicago, we have to be prepared and willing to not just make sacrifices, but to humble ourselves to something that’s bigger than us.”

Johnson is indeed a member of something bigger — a movement whose success and influence will depend on how he handles the mayoralty. “I think there are a wide range of forces that are looking to see Brandon Johnson fail precisely so that there can be a return to business as usual in the city,” Jacobin’s Uetricht says. “If he succeeds, it wouldn’t surprise me to see other cities around the country taking up that mantle, very explicitly drawing from the CTU’s model of the teachers’ union as the anchor institution of a broader left-labor world, with a true grassroots army.”

Johnson was in and out of the Muslim Community Center in less than 45 minutes — he needed to head downtown for a fundraiser with supporters. That’s the reality of being Brandon Johnson these days.

“Yo, for real, I wake up and put on a suit, I get in a car, and they just drop me off, man,” he says of the packed schedule meticulously mapped out by his handlers. “I’m not saying I’m not enjoying myself, but nobody tells me anything anymore.” That’s a long way from living in a house with no lights or water. But Johnson has to stay in touch with those days in Elgin if he wants to fulfill the progressive promise he made to Chicago.