1 Lincoln didn’t campaign as an abolitionist.

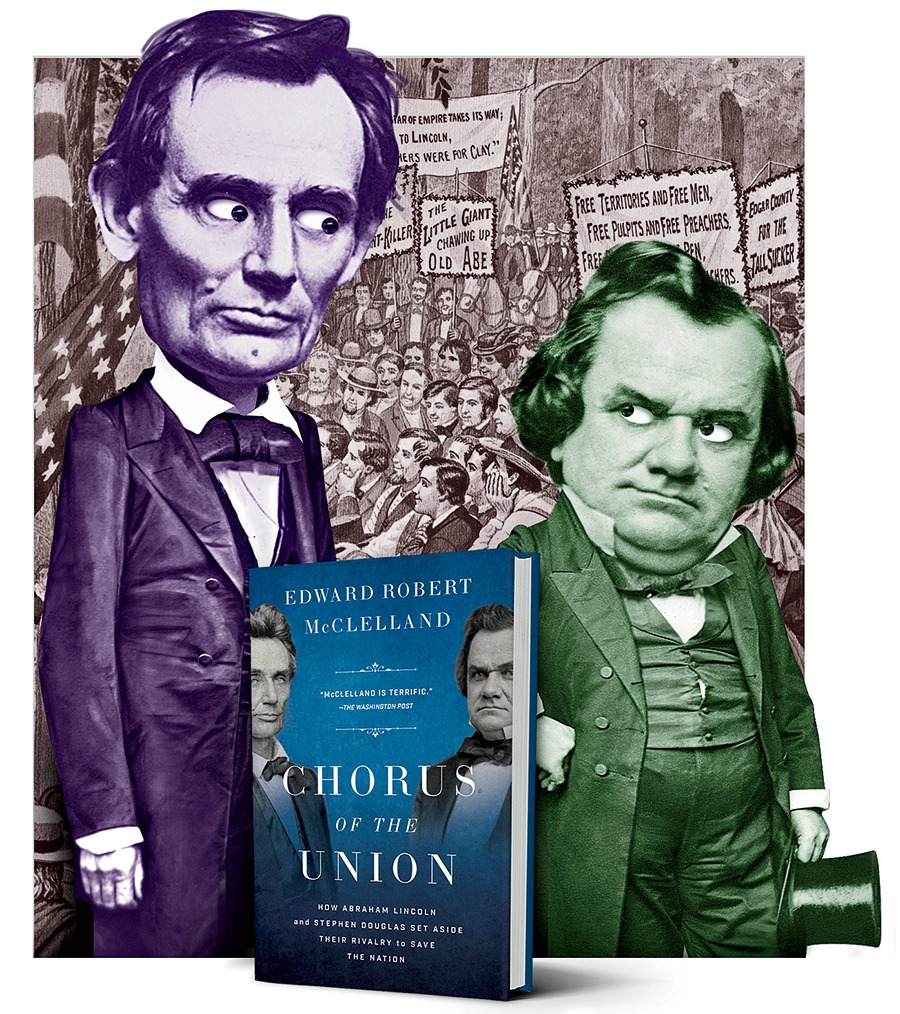

That would have been too radical for most voters to stomach. Instead, the Republican insisted slavery shouldn’t be expanded into territories and new states. His allies “recognized that his political career in half-Yankee, half-Southern Springfield,” where he’d had to find middle ground, “would make him the perfect compromise candidate for the presidency,” Chicago contributing editor Edward Robert McClelland writes in Chorus of the Union, out June 4.

2 Railway boosterism was a major motivator for Douglas.

And if that meant the expansion of slavery, the Democratic senator, who’d helped create the Illinois Central Railroad, was fine with it. “Eager to boost Chicago as a rail hub, Douglas agreed to the South’s demand that the settlers a railroad would bring to Nebraska be allowed to decide for themselves” whether to adopt slavery.

3 Lincoln tailored his messages for his audiences.

During their 1858 Senate campaign debates, Douglas accused him of swaying to local political winds. Galesburg was where Lincoln declared that slavery was “a moral, social, and political evil.” But he avoided such rhetoric when they debated in southern Illinois. For his part, Douglas refused to say if slavery was right or wrong, arguing that the Constitution was silent on the question. Each state could “do as it pleases,” he said.

4 Lincoln stayed home in Springfield during the 1860 presidential race, saying little.

The presidency was “too dignified to be canvassed for like a county clerkship or a seat in Congress,” said the New York Times, which criticized Douglas for barnstorming the country. In contrast, writes McClelland: “Lincoln’s silence made him appear more confident and dignified.”

5 Douglas urged Southerners not to secede.

In the final weeks of that campaign, as it became clear Douglas would lose, he said: “Mr. Lincoln is the next president. We must try to save the Union.” Then, as war broke out, Douglas implored the North’s Democrats to support the new president. Speaking to the Illinois House, he declared: “Give me a country first, that my children may live in peace.” Writes McClelland: “It may be regarded as the greatest argument any politician has ever delivered on setting aside partisanship in a time of national crisis.” Douglas soon fell ill and a month later died in Chicago.