Keeping an eye out for approaching trains, I walked across the rails along Brainard Avenue at the state line, stepping onto a scrubby patch of land wedged between various sets of tracks. There wasn’t much to see — shrubs, discarded liquor bottles, piles of rocks. On the morning I visited this spot in south suburban Burnham, the air rang with the shrill shrieks of blue jays and red-winged blackbirds, occasionally drowned out by the clatter of freight cars or a South Shore Line passenger train. Looking east into Indiana, I spotted Uncle Sam’s Fireworks Store roughly 200 feet away. Not surprisingly, the vacant land I walked didn’t have any sort of commemorative plaque or historic marker about the events that transpired here a century ago — it’s not the kind of history that inspires civic pride. If my research was correct, this could be the spot where Al Capone was arrested by Illinois authorities for the first time.

I got interested in this place when I was reading up on Capone’s early years in Chicago, a sketchy period of his life. A young thug from New York City, Capone arrived here as early as 1919 or as late as 1921, according to various biographers and authors. “The details of Al Capone’s first three or four years in Chicago are somewhat minimal, with little mention of him in the press,” Chicago mob historian John J. Binder wrote in his 2017 book Al Capone’s Beer Wars: A Complete History of Organized Crime in Chicago During Prohibition.

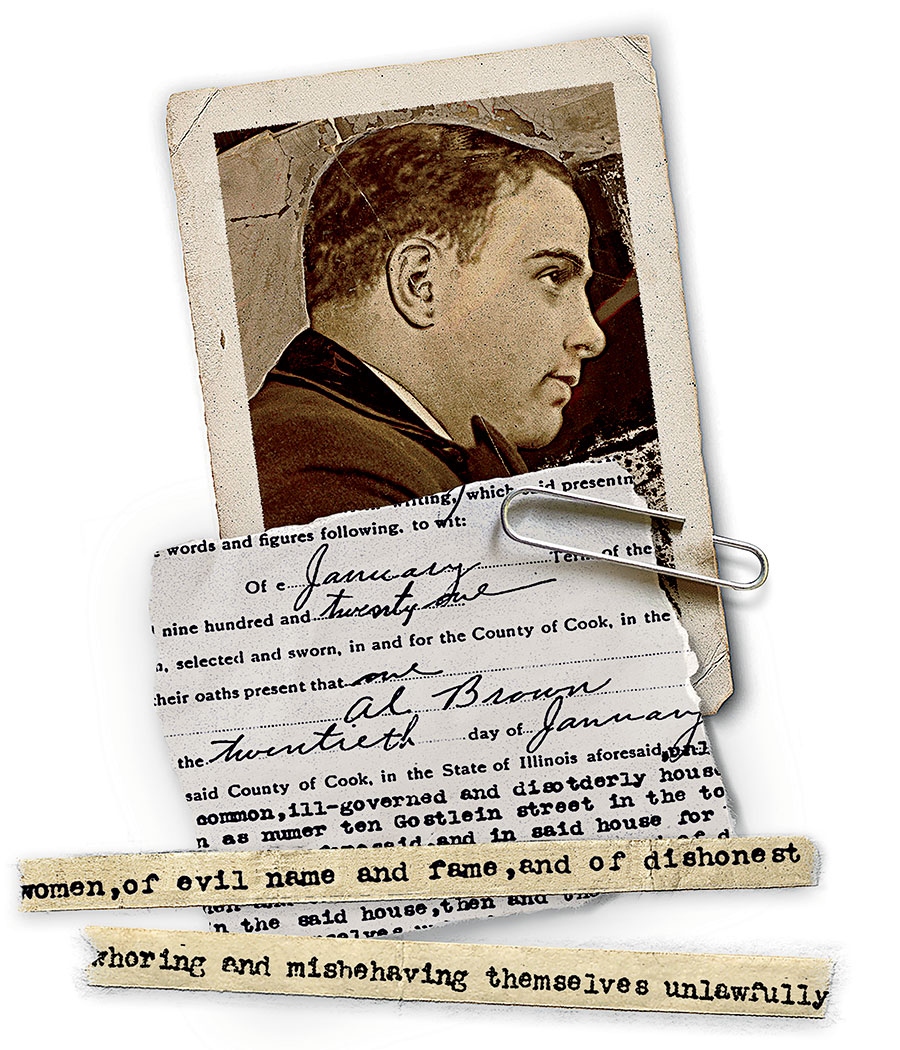

As Binder pointed out, a man using the name Al Brown was arrested in January 1921. Capone often used Al Brown as an alias — as late as 1927, the Tribune would still refer to him by this name — so there’s a strong possibility that this was Al Capone, who’d just turned 22. Of course, it could’ve been someone actually named Al Brown — or another criminal hiding behind the same alias. It was a lot easier to get away with using an alias in 1921 than it is today.

The circumstances of Al Brown’s arrest match up pretty closely with what we know about Al Capone. This Al Brown was running two roadhouses in Burnham, which is just south of the Chicago city limits, along the border with Indiana. The village (named for developer Telford Burnham, not for the famed urban planner Daniel Burnham) had a population of 795 in 1920. The Tribune observed back then that it was notorious as a “den of vice,” replete with gambling, prostitution, and saloons that stayed open all night. A federal prosecutor called Burnham “the leper of Illinois.” The town earned that reputation thanks in part to its “boy mayor,” Johnny Patton, who was just 24 when he was first elected in 1908. “The mayor says the town is open — all night, all Sunday, all any time that there is anyone there who’d like to buy a drink or to dance to the sound of a nickel piano,” the Tribune reported in 1916.

This suburban outpost with a laissez-faire mayor provided an attractive location for the folks who’d run brothels in the South Side’s Levee before 1912, when authorities cracked down on that red-light district. Mobsters including South Side boss Johnny Torrio ran Burnham’s roadhouses and brothels, so it wouldn’t have been surprising to find Capone working there circa 1921, when he was an up-and-coming member of Torrio’s mob.

Curious to learn more about Al Brown’s arrest, I headed to room 1113 of the Daley Center. That’s the Cook County Circuit Court’s archives, where I’ve gone many times on quests for old documents. One thing I’ve learned is not to get your hopes up about finding anything like a trial transcript. There are many gaps in the historical record. For example, all files for criminal cases from 1900 to 1927 were discarded a long time ago. But other documents have survived, including grand jury indictments.

Ace archivist Julius Machnikowski, who always seems to know where documents are stashed away, helped me find microfilm of the indictments of Al Brown from January 27, 1921. The charges alleged that Brown had one slot machine — “a device upon which money is staked and hazarded” — in each of his two roadhouses, at 10 and 18 Gostlin Street in Burnham.

Cook County state’s attorney Robert Crowe and the grand jury also accused Brown of keeping a “common, ill-governed and disorderly house” at one of these locations, 10 Gostlin Street. The euphemism “disorderly house” was often used in those days for brothels, as well as saloons where prostitution and similar activities occurred. These were places regarded as public nuisances.

In Brown’s case, the grand jury said he’d “caused and procured” certain men and women “of evil name and fame, and of dishonest conversation” to “frequent and come together” at this place, where they engaged in “drinking, tippling, whoring and misbehaving themselves” at “unlawful hours, as well as in the night as in the day.” Brown was allegedly allowing all of this to happen “for his own lucre and gain.” And the grand jurors noted that this activity contributed “to the great damage and common nuisance of the inhabitants of the … State and to the evil example of all others.”

Al Brown — a.k.a. Alphonse Capone? — pleaded guilty to the charges and was fined $150, roughly $2,500 in today’s money.

I might have ended my research there, but Machnikowski said, “You know what I would do?” He suggested looking up property records, which might offer more clues about the scene of Brown’s alleged crimes. Only one problem: The addresses 10 and 18 Gostlin Street no longer exist. So where exactly were these notorious roadhouses? There is a Gostlin Street in Hammond, Indiana, but when it crosses the state line into Illinois, it becomes Brainard Avenue and veers northwest. The roadhouses must have been somewhere in that vicinity. According to a 1918 Tribune story, Burnham’s “roadhouse district” included four saloons and two brothels “only a few feet from the Indiana line.”

My next stop was the basement of the County Building, where Cook County keeps books listing old property transactions. Parsing these documents can be a little like deciphering coded notations scribbled by medieval monks. And I faced an extra challenge: I didn’t have a property description or a property identification number. All I had were obsolete addresses and a vague notion about where the roadhouses might have been.

After a first and fruitless visit, I went online and found a map on which this area near the state line was labeled “5-36-15”: section 5, township 36 north, range 15 east. So when I returned to the County Building’s basement, I poked around, looking for those numbers. That led me to an index of plat maps showing property lot lines. Those maps revealed that Brainard Avenue used to be in a different spot, roughly a hundred feet south of where it is today. Back when Al Brown was arrested in 1921, Gostlin Street had extended straight across the state line for a short distance before it turned northwest and became a street called Howard Avenue (a.k.a. “Old Brainard Avenue”).

In the tract book listing property transactions, I found notations offering another clue about a possible Capone connection: State and county prosecutors had sued property owners in this little corner of Cook County in 1919 and 1923. That information in hand, I went back to the court archives in the Daley Center and requested to see the lawsuits. They were retrieved from a warehouse, a process that took two weeks, and I got a look at files whose pages probably hadn’t been unfolded for a hundred years.

Those documents confirmed that I was looking at the correct properties. They said the “disorderly house” where Al Brown was arrested was called the Speedway Inn. And they revealed a link with Capone: In 1919, the Speedway was under the control of Jake “Greasy Thumb” Guzik, a Torrio mob member who later became one of Capone’s closest associates (as well as a character in the TV shows The Untouchables and Boardwalk Empire).

The Illinois attorney general accused Guzik and the other roadhouse proprietors of serving drinks to minors and habitual drunkards. State investigators said they’d witnessed “loiterers, drunkards, and dissolute persons” inside the saloons, as well as “persons who indulged in low-vulgar, profane, and obscene language.” People “were lying upon the streets and upon adjacent lots, in a drunken condition.” According to the attorney general, these saloons encouraged “lawlessness, dissipation and debauchery.”

“Al Capone’s syndicate owned a piece of the Arrowhead, as well as the whole town,” a jazz musician who played in Burnham recalled.

The Tribune reported that Indiana’s governor had complained to Illinois authorities about these places along the state line, as well as the neighboring brothels, urging them to take action. Barkers would stand outside the establishments, urging passersby to enter. Most of the patrons came from northwest Indiana, but the Tribune noted that people were also driving down from Chicago. “Deputy sheriffs patrolled the streets of Burnham and the roadhouse district adjoining, herding more than 200 immoral women into custody,” the newspaper wrote. “All were given their choice of submitting to medical examinations and treatment at the state’s expense or having big red cards labeled ‘Venereal diseases here’ placarded over the doors of places where they reside.”

The prosecutors also sued Kitty Walters and Mabel Young, who were allegedly running brothels. The allegations contain more than a tinge of Victorian era moralism. Not only were the women employed there accused of violating the law against prostitution — they were also condemned for practicing “fornication and adultery” and for being “lewd, immoral, and depraved.” The attorney general warned that “youthful inhabitants of the community” had been “debauched, enticed, and lured away from lawful and profitable pursuits and educated in evil and vicious habits.”

A judge issued temporary injunctions against the Speedway Inn and the other roadhouses, but the lawsuits were then dismissed. At the time, the Speedway’s address was given as 10 Howard Avenue. But when authorities sued the owners again, four years later, the address had changed: It was now 10 and 12 Gostlin Street. This time, investigators said they’d made dozens of prostitution arrests at the Speedway.

Al Brown was not mentioned in the 1923 litigation. But this was around the time when Capone was a regular at the nearby Arrowhead Inn, where jazz clarinetist and saxophonist Milton “Mezz” Mezzrow would play with his band. “Al Capone’s syndicate owned a piece of the Arrowhead, as well as the whole town,” Mezzrow recalled in his memoir, Really the Blues, written with novelist Bernard Wolfe.

Unlike the prosecutors’ fire-and-brimstone rhetoric, Mezzrow wrote about Burnham’s red-light district with a playful tone. He seemed to take delight in performing for the town’s “good-natured and sociable” sex workers whenever they stopped into the Arrowhead. “I used to walk from table to table, playing request numbers on my horn while one of the entertainers sang,” he recalled. “I never in my life saw a flock of chicks who could turn on the weeps so fast when we played their favorite tearjerkers.” In Mezzrow’s estimation, Burnham had “more whores per square foot than in any town in the good old U.S.A.” He also made this claim: “The town was better known to tourists than Niagara Falls — it was a kind of Niagara Falls, strictly the one-night-stand type — and important visitors from every state in the Union dropped around to snag a honeymoon between trains.”

The Speedway Inn closed in the early 1930s, around the time that the new Brainard Avenue replaced the old roadways and that Al Capone, by then known far and wide by his legal name, went to prison for tax evasion. By 1944, the Hammond Times was calling Burnham “a model community.” The four-decade reign of the village’s “boy mayor” finally came to an end in 1948.

These days, Burnham, which has a racially diverse population of about 4,000, is rarely in the news — and certainly not for anything like what it made headlines for back in Capone’s day. I know it mostly as a place to visit for nature walks and birding. Powderhorn Lake, a popular fishing spot, is just northwest of the former roadhouse district. And the Burnham Woods Golf Course is south of all those railroad tracks.

I didn’t expect to find much when I visited that vacant land, now owned by the South Shore Line. We’ll never know for sure if the Al Brown that was arrested there in 1921 was actually Al Capone. I had no Geraldo Rivera–like expectations of finding a secret Capone vault. It’s hard to tell if any traces of the old roadhouses remain. But even when a place’s history is hard to see, I still find it fascinating to look around and think about what once happened there, imagining the scene a hundred years ago.

After exploring that spot, I headed to the lovely Burnham Prairie Nature Preserve, on the other side of town, and took a walk along the marshes, listening to the distant calls of sandhill cranes and watching some downy woodpeckers and mute swans. I wonder if Al Capone ever paused to look at the birds.