Excerpted from How to Watch Basketball Like a Genius: What Game Designers, Economists, Ballet Choreographers, and Theoretical Astrophysicists Reveal About the Greatest Game on Earth by Nick Greene, to be published on March 2 by Abrams Press. Copyright © 2021.

There’s something both comforting and distressing about watching old basketball games. Knowing the results takes away the suspense, and so the broadcasts take on the character of a lava lamp. It’s easy to get lost in the glow of the action as it flows back and forth across the screen. That part’s nice. The distress comes in the form of nostalgia, and the realization that the games you watched as a kid look fuzzy (literally, as there were no high-definition cameras) and out of sync with the rhythms of today’s basketball. The pace is slow — sometimes frustratingly so — and the 3-point line just sits there, unused, like Mr. Chekhov’s firearm. The contests are still enjoyable, just different. If anything, you get to appreciate the things about the game that are impervious to change, like Hubie Brown and free throws.

The other day I rewatched game 1 of the 1997 finals between the Bulls and the Jazz. The teams were tied 82 to 82 with 9.2 seconds remaining in the fourth quarter (told you it was slow) when Dennis Rodman and the Jazz’s Karl Malone collided while trying to grab a loose ball. The officials whistled Rodman for a foul, gifting Malone two freebies and the chance to hand Utah a late lead.

Malone was the league’s MVP that year and one of the most reliable scorers on the planet. This dependability was reflected in his nickname, the Mailman. He finished his career second on the list of the NBA’s all-time leading scorers, and a huge chunk of those points came at the line. He took the most free throws in league history (13,188) and made more than anybody else (9,787). His 74.2 percent success rate is commensurate with the leaguewide average.

When Malone stepped to the line in Chicago, he did the same protracted routine he performed before every attempt: He bounced the ball repeatedly (seven times, in this instance), spun it in his hands twice, and whispered a few words to himself. What he said before releasing his shot was a point of mystery and fascination in Utah, but Malone never divulged it. That year, the Salt Lake Tribune hired two lip readers to analyze close-up footage, and they determined that Malone used these moments of relative solitude to deliver a message to his son: “This is for Karl. Karl, my baby boy.”

A foul shot can be intensely personal. It is the only time during a game when your teammates and opponents are powerless to help or hinder your success. There may have been 21,000 screaming, largely drunk Chicagoans letting Karl Malone have it that Sunday afternoon at the United Center, but he was as alone as a basketball player can be. The island was familiar, even if the water surrounding it churned harder than ever before.

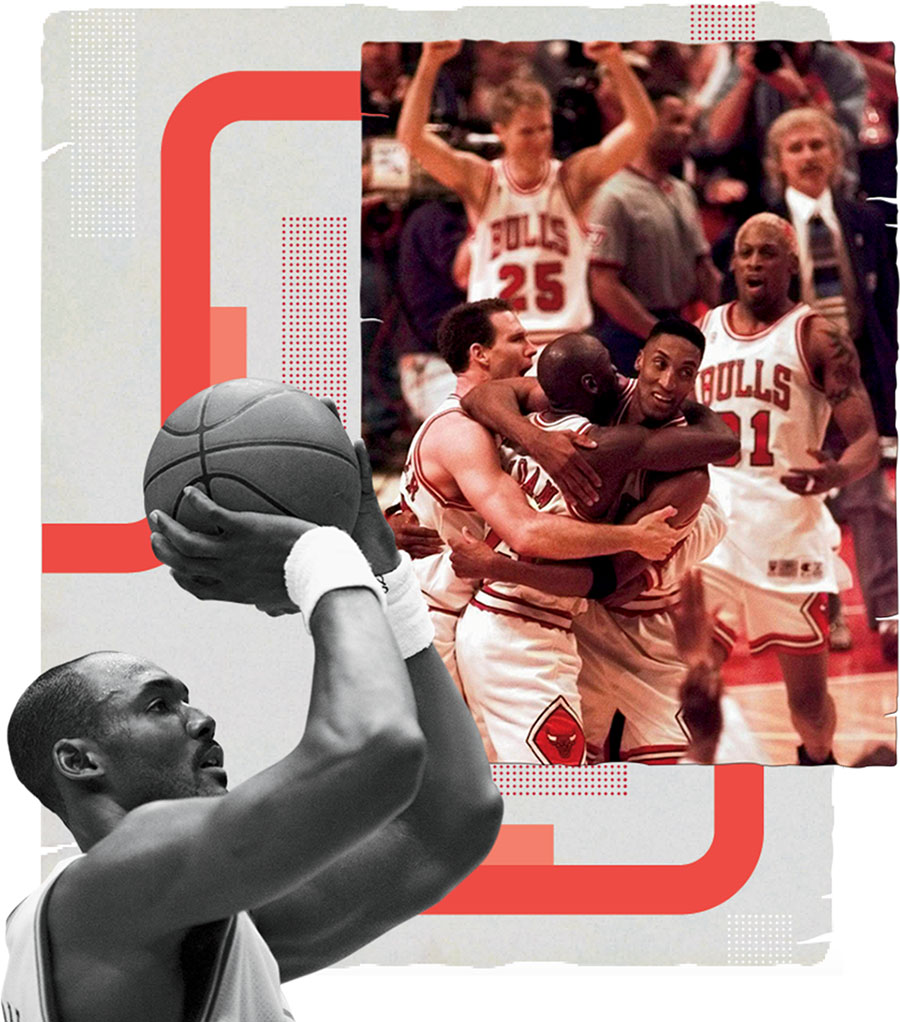

OK, I’ll stop with the Jack London crap. You probably just want to hear what happens next (or you already know): Malone misses both attempts, the Bulls get the rebound, and Michael Jordan hits a buzzer-beater over Bryon Russell for the win.

Adding insult to Malone’s agony was Scottie Pippen. After the game, the Chicago forward told reporters that he had whispered something in Malone’s ear, interrupting the Jazz star’s routine as he prepared to take the first of those two fateful free throws. Pippen’s trash talk is now legendary: “The mailman don’t deliver on Sunday.”

It’s a great line, and for decades, I thought I had seen Pippen deliver it with my own two eyes. However, upon rewatching the game, I know this to be a false memory. The cameras didn’t capture him issuing his bon mot — all viewers got to see was Malone’s long routine, the ball rimming out of the hoop, and his agonized wince.

There was another aspect of the game’s ending that I had pushed to the far recesses of my mind. Right before Rodman’s foul on Malone, Jordan had a chance to give the Bulls the lead from the foul line. He made the first attempt but clanked the second, which is why the score was knotted at 82. As if out of some cosmic arrangement, Jordan’s stumble set into motion a sequence of events that resulted in yet another highlight-reel moment of greatness. All foul shots are the same, except when they aren’t.

Professional basketball players have a lot to think about. The flow and pace of the game may be a good distraction, but what happens when everything grinds to a halt? You’re isolated on the foul line with nothing to focus on but the hoop and a frozen clock. What’s the mind supposed to do then?

Paula Kout saw firsthand just how difficult it can be for NBA players to slow down. Phil Jackson hired her to teach the Bulls some basic yoga principles before the 1997–98 season. “The players had no frame of reference for it,” she tells me. “If you take a player today and tell them they are going to do yoga, well, everyone does yoga.” Back then, however, the practice was practically unheard of, and the Bulls organization was so skeptical of its benefits that Jackson had to pay Kout with his own money.

“I was taking a bunch of guys who had spent their whole lives in one mindset, one method of training their bodies,” she says. Getting Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen into downward-facing dog was a bit odd at first, but everyone on the team was open to the experience. “They were such good sports,” she recalls. The biggest surprise, though, came during the quiet moments.

These were the only times in their professional lives, Kout believes, that someone told them to do nothing. “Don’t succeed. Don’t excel. Don’t be aggressive.” She loves to imitate Dennis Rodman doing shavasana, or corpse pose, where you lie still on your back. “He would be lying on his mat with his eyes closed, drumming his fingertips on the floor.” He had no idea how to not do anything. (Rodman’s career free-throw percentage: 58.4 percent.)

“That moment of doing nothing wasn’t the prelude to something that was demanding pressure and stress,” Kout says. “It was a total free space on the bingo card. Do nothing now, and do nothing afterward.”

Karl Malone could have benefited from doing nothing after missing that first free throw. Watching the replay, it’s obvious that the man’s mind is racing. He saunters toward half-court with furrowed brow and grunts a word of frustration that likely upset Utah’s finest lip readers.

Malone clearly didn’t feel great, and his second attempt against the Bulls reflects this. The ball dips tantalizingly below the rim and then spins out and to the left — an identical reproduction of the first shot. He learned nothing. Those initial mistakes concerning arc or hertz or speed were copied and pasted into the fibers and sinew of Malone’s kinesthetic machinery and produced an agonizing sequel.

“I think both of them were right on line,” Malone’s teammate Jeff Hornacek said while doing some quick motion modeling in his head. “I think it was a case if it was a half-inch shorter, it would have hit the rim, bounced off the backboard, and went in. If it was a half-inch farther, it would have been a swish. Both free throws were right there, but a half-inch here or there makes a difference.”

Malone failed basketball’s most repeatable experiment, but Chicago’s Steve Kerr credited the laboratory conditions for the Bulls’ fortunate break. “That rim down there the last two months has been loose because of our mascot dunking all the time,” he dished to a reporter after the game. Chicago was experimenting with a newer and more extreme mascot at the time named Da Bull. Unlike the charming and portly Benny the Bull, Da Bull was a buff daredevil who entertained the crowd with fierce, trampoline-assisted slams during breaks. According to Kerr, Da Bull’s antics loosened the rim at one end of the court so severely that a maintenance crew had to come in and tighten its mechanism before game 1 against the Jazz. “And thank God, because both those free throws were right there,” Kerr said. “They tightened them up just right.”

Karl Malone made more foul shots than anybody else in NBA history, but he is remembered for two misses against the Bulls that may have rolled out because of an overzealous mascot.

All free throws are the same, except when they aren’t.