On February 21, 2020, Chester Otto Weger, prisoner C-01114, stepped out of far-downstate Pinckneyville Correctional Center into the cool air of an overcast morning. It was the 21,646th day behind bars for the state’s longest-held inmate. It would also be his last.

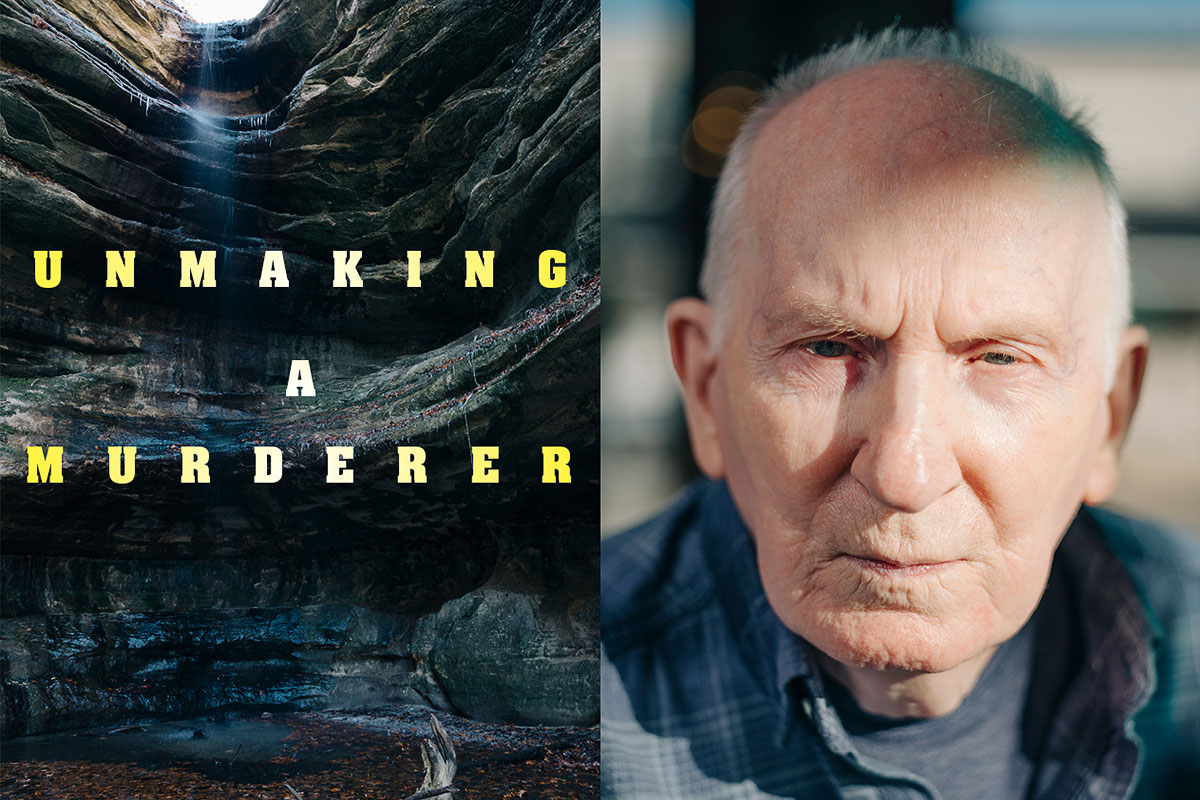

When he ceased to be a free man back in 1961 and became known far and wide as the Starved Rock Killer, Weger was only 22, a chain-smoking ex-Marine, avid hunter and fisherman, and married father of two young children. In those days he had James Dean’s swooping pompadour and svelte build, if not quite a matinee idol face. But now, at the age of 80, he showed signs that he had been hobbled by time served in concrete-and-steel cages all over Illinois — at Stateville and Menard and Pontiac and Graham. He was down to only 113 pounds, his pale scalp encircled by a faint halo of short gray hair that he no longer bothered running a comb through. Emphysema made breathing a struggle, and the pain of rheumatoid arthritis limited his movement.

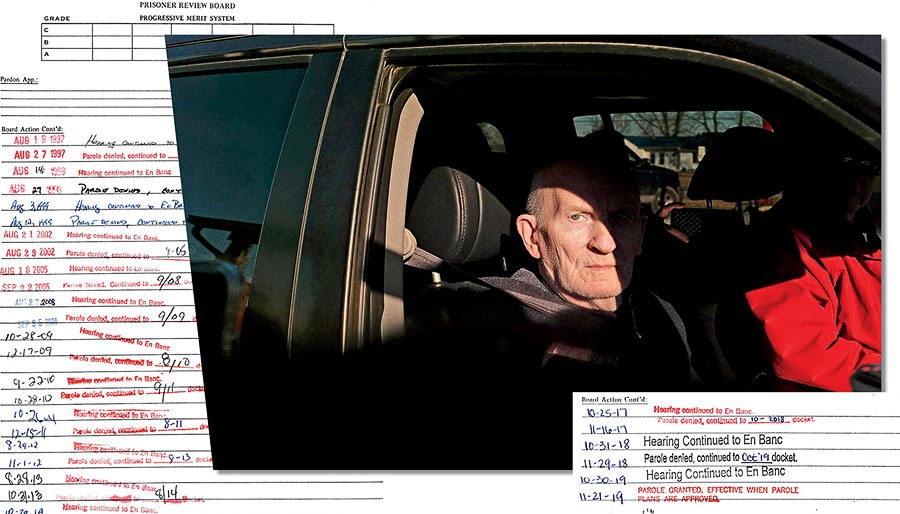

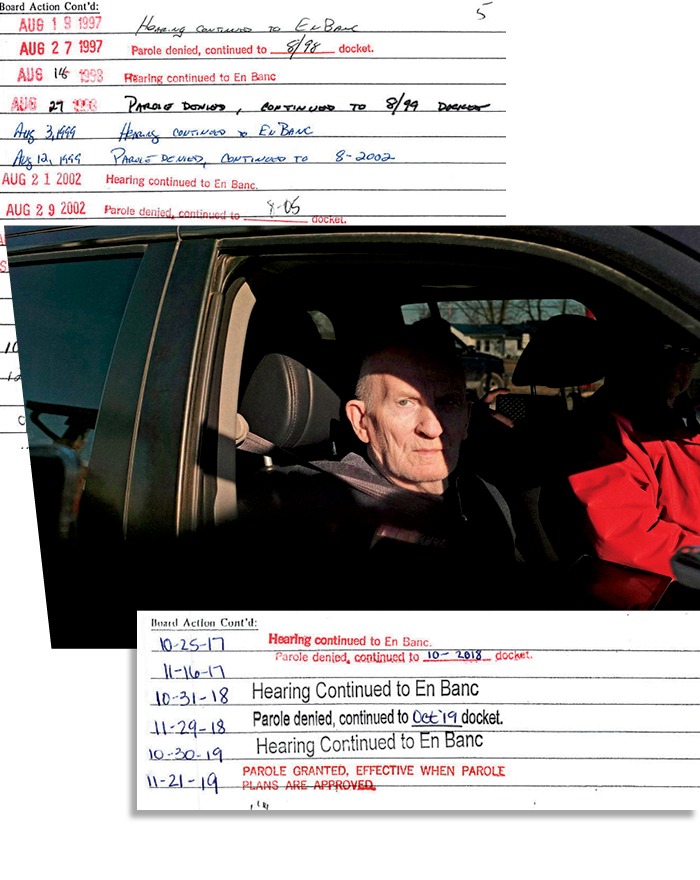

Three months earlier, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board had met to decide Weger’s fate. Would he be granted parole, or would he continue to serve out a life sentence for murder in connection with one of the most notorious cases in Illinois history: the 1960 triple homicide at Starved Rock State Park? He had long been aware that the board wanted him to express remorse and that not doing so would almost certainly doom his chance of early release. But year after year, over the course of 23 hearings since he became eligible for parole a half-century ago, he refused. His claim of innocence, he said, was all he had to cling to. That immovable stance made the conclusion of his 24th hearing all the more stunning: a vote of 9–4 in favor of release.

As the prison doors swung open, Weger saw his beloved younger sister, Mary Pruett, as well as her husband and two daughters, who had lobbied the Prisoner Review Board for the man they lovingly call Uncle Otto. Later that evening over dinner, Weger would reunite with his children, Rebecca and John, who were ages 3 and 1, respectively, when their dad was locked up. Pruett, who was a teenager during Weger’s trial, had bawled in court when the guilty verdict was read. Through the years, she wrote and called and visited frequently, but she had not been allowed to embrace her brother in the 59 years he was behind bars.

Weger’s family agreed they’d never seen him smile like he smiled that day. The prospect of freedom after so long was exciting — and, for an institutionalized man such as Weger, terrifying. The mere glimmer of hope of this day’s arrival, he says, kept him alive, comforting him on the many dark nights alone in his cell when he doubted he’d live to see it actually come.

Wearing a dark hooded sweatshirt, Weger gingerly folded himself into the passenger seat of his niece’s gray Honda SUV. The vehicle carried Weger over the flatlands of southern and central Illinois, toward St. Leonard’s Ministries, a halfway house in Chicago where he would initially reside as a stipulation of his parole. Through the windshield, he watched a strange new world speeding by. He marveled at the oddly futuristic-looking vehicles along the highway, drivers guided by a talking map on a wireless phone that had more computing power than an Apollo spacecraft. He had missed so many moments, from the moon landing to the entire lifespan of the internet, but also his parents’ funerals and nearly all of his children’s birthdays. He knew little of fast food. At one point, the Honda pulled into a McDonald’s drive-through, and Weger ordered his first postrelease meal, a biscuit sandwich.

In the midst of the 300-mile journey, Weger’s thoughts drifted back, as they often did, through the fog of decades of incarceration, to the tragic, twisted events that led to his imprisonment.

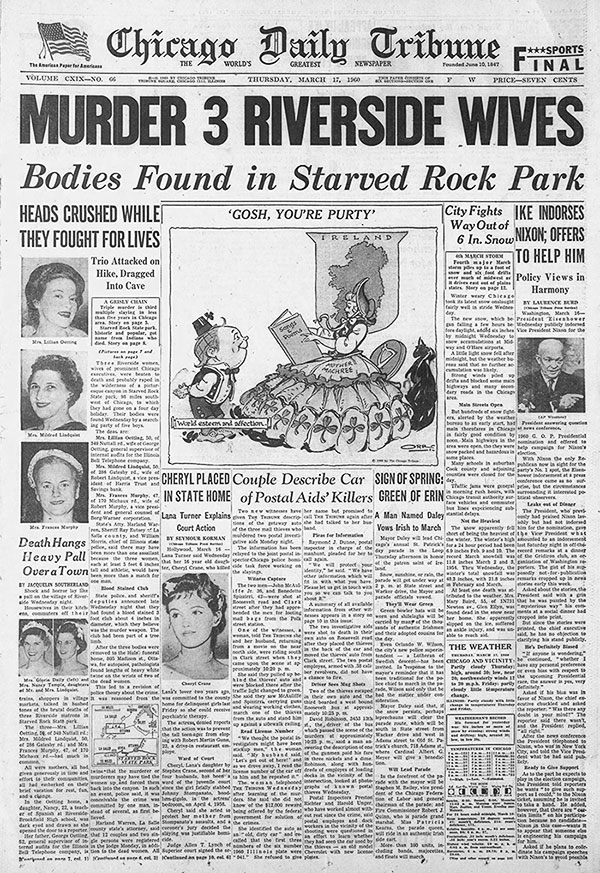

On March 14, 1960, three women from west suburban Riverside — wives of Chicago corporate executives and prominent members of Riverside Presbyterian Church — departed on a midweek vacation to Starved Rock, one of the state’s most picturesque sites, located on the Illinois River in LaSalle County, 90 miles southwest of the Loop. They were drawn to the park, like more than two million tourists still are each year, by its glacier-carved sandstone bluffs and canyons, its dramatic waterfalls, its miles of wooded trails snaking across what was then 1,500 acres. Two days later, the women were reported missing. Soon thereafter they were found dead, their bludgeoned bodies lying in a cave within a scenic canyon.

The crime made headlines around the world and triggered what was then the most resource-intensive manhunt in state history. But it wasn’t until several months later, after the investigation had stalled, that the authorities zeroed in on Weger, who had been employed as a dishwasher in the lodge kitchen at the time of the killings. After professing his innocence for a month in the face of constant surveillance and repeated interrogation, Weger finally broke down and confessed. He soon recanted, testifying that police coerced him. But by then it was too late, and he was convicted largely on the basis of his own words.

It was only the beginning of what would become one of the most widely publicized and fiercely debated criminal justice sagas in Illinois history, a kind of heartland noir that has played out over the course of three generations, sparking numerous articles, a book, and most recently an HBO documentary. In the enclave of quaint riverside towns near Starved Rock known as the Illinois Valley, where I was born and raised and where much of my family still lives, the murders have been endowed with the mythic quality of folklore, a sepia-toned ghost story recounted in hushed tones around campfires. But that petrified tale told by the townspeople oversimplifies what in truth is a knotty epic of crime and punishment studded with conflicting narratives, questions of reasonable doubt, allegations of misconduct, and a host of alternate theories. And Weger’s release from prison kicked off a wild new chapter.

“I don’t want to die with people thinking I’m guilty of a crime I never committed.”

Many men in a similar position might decide to live out the remainder of their days quietly, basking in the glow of family and attempting to make up for lost time. But now that his day of liberation had finally arrived, Weger knew exactly what his next move would be. He had been telegraphing it for half a century. Back in 1972, before what was Weger’s second parole hearing, a Prisoner Review Board member had visited him at Stateville Correctional Center and asked about his plans were he to be released. Without a thought, Weger replied that he would seek, by all legal means, to prove his innocence.

And now he has that opportunity. In October, his pro bono lawyers — veteran trial attorneys with experience in exoneration cases — received permission from the LaSalle County Circuit Court to submit evidence recovered at the crime scene for DNA testing. Weger hopes the analysis will help him finally clear his name — perhaps by revealing the identity of what he calls the true killer.

“It’s the only thing I want,” he told me over the phone one evening in the midst of the push for testing. “I want that more than anything else.”

He was speaking from his room in the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center on the Near West Side, his temporary residence at the time, before his family secured him permanent housing in LaSalle County. He talked of prison food (not as bad as you’d think), his recurring dreams (about family, mostly), the career he would’ve wanted (police officer, oddly), and the simple pleasures of his newfound freedom (buying candy at the convenience store). The line was plagued by static. And the 82-year-old, never one to offer more words than necessary, was reserved and soft-spoken.

But one thing he said came through loud and clear: “I don’t want to die with people thinking I’m guilty of a crime I never committed.”

Weger has made this same proclamation for 60 years. What’s different now is that he finally has a chance to prove it.

The first sign that something was wrong was an unanswered telephone call to room 109.

On the evening of Monday, March 14, 1960, George Oetting dialed the lodge at Starved Rock State Park to check in with his wife, Lillian. The phone rang and rang, but no one picked up.

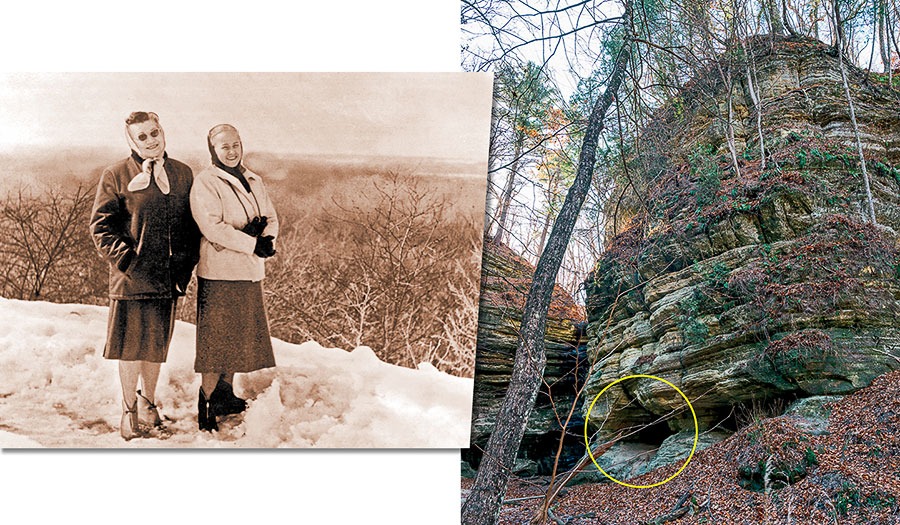

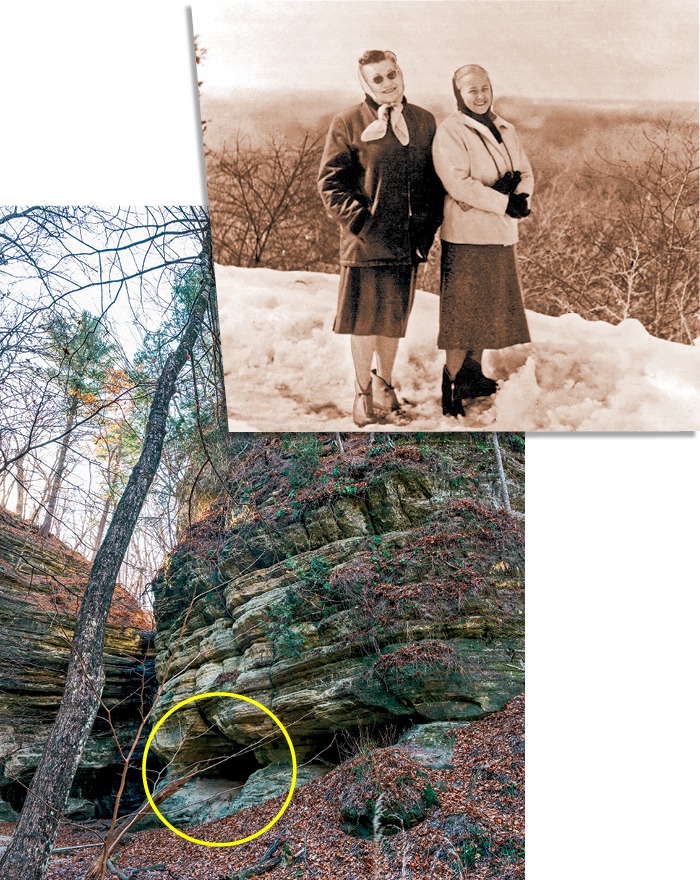

That morning, Lillian, 50, and two friends, Mildred Lindquist, 50, and Frances Murphy, 47, had hopped into Murphy’s gray Ford station wagon and left behind their upper-crust domestic lives in Riverside. It was on a whim after that Sunday’s church services that they planned the trip — a leisurely four-day getaway to Starved Rock.

Around 12:30 p.m., the women checked into adjoining rooms in the lodge. In the dining room, they had a lunch of chow mein, juice and coffee, and cake and a sundae for dessert. They returned to their rooms to change into clothes suitable for the day’s sunny but wintry conditions. Then the trio departed for a hike, carrying little aside from a camera and a pair of binoculars.

It would be among the last times they were seen alive.

For months before the trip, Lillian had kept watch over George, who had suffered a heart attack that prompted an extended leave from Illinois Bell Telephone Company, where he worked as a general supervisor of internal audits. Mildred and Frances believed their friend deserved some rest and relaxation away from the house, out in the splendor of nature. But before Lillian left George’s side on Monday, she made her husband a promise: She would phone later that night to make sure all was well at home.

When the call didn’t come, George rang the lodge and asked for his wife’s room. A switchboard operator attempted to connect him, but there was no answer. By Tuesday evening, George still hadn’t heard from Lillian. He made additional attempts, and still no one picked up the ringing phone in room 109. The desk clerk on duty told George that he was welcome to leave a note for his wife. The message, George said, was simple — call home immediately.

Early on the morning of Wednesday, March 16, George tried and failed once more to reach his wife. He felt a hot wave of panic sweep over him. Where on earth were Lillian and the girls?

Around 6:45 a.m., George’s brother, Herman, an accountant living in nearby Berwyn, had heard about his difficulty getting in touch with Lillian. Herman began his own efforts. When he had no luck by phone, he asked that the desk clerk check the women’s rooms. It was then that the clerk reported back a jarring find: the beds in the rooms appeared neatly made, almost as if they hadn’t been slept in, and the ladies’ bags remained inside the rooms. Herman then requested that the parking area be checked for a station wagon whose license plate carried a Riverside sticker and was informed that the vehicle was indeed parked in a spot near the main lodge entrance. The grave reality of the situation could no longer be denied: His sister-in-law and her friends had disappeared.

That’s when Herman phoned Frances’s husband, Robert Murphy, a vice president and general counsel for Borg-Warner Corporation, and Mildred’s husband, Robert Lindquist, a vice president of Harris Trust and Savings Bank. They, too, had not heard from their wives since they left for Starved Rock. Murphy contacted LaSalle County sheriff Ray Eutsey to report the women missing. He also notified Virgil Peterson, a friend of the three families and director of the Chicago Crime Commission, an organization of civic-minded business leaders determined to snuff out organized crime. A former FBI agent whose connections in law enforcement ran deep, Peterson told Murphy he would call the chief of the Illinois State Police to assist in the search for the missing women.

Late Wednesday morning, parties of state and local police and volunteers fanned out across Starved Rock. By that time a severe winter storm had moved into the region, dumping several inches of snow that added to the challenge of traversing the park’s rugged terrain. Despite the inclement weather, it took only about 90 minutes for a volunteer group of boys from a forestry camp for juvenile offenders in nearby Marseilles to come upon the battered, bloodied bodies of Lillian, Mildred, and Frances on the floor of a shallow cave within St. Louis Canyon, one of the park’s most scenic locations, a little more than a mile from the lodge. The women, two of whom were naked from the waist down, had been bound with twine and brutally bludgeoned beyond recognition. Outside the cave, in the shadow of the canyon’s 80-foot sandstone walls, blood and other evidence were encased under the quickly accumulating snow. The only witness, it seemed, was the canyon’s waterfall, frozen into a monumental icicle.

This was not the first time blood had been spilled at Starved Rock. In fact, the park was built upon the site of a Native American massacre. In 1769, according to legend, the Ottawa and Potawatomi tribes surrounded a band of Illinois (who had been responsible for the assassination of the Ottawa chieftain Pontiac) and stranded them high on a bluff — effectively starving them of food and water. When the Illinois attempted to escape, they were violently killed, some bludgeoned to death.

In 1960, in the immediate aftermath of the gruesome discovery of the three murdered women, a dark cloud of fear and paranoia descended on Starved Rock and the Illinois Valley. With a killer or killers on the loose, an entire community that had never before considered locking its doors was suddenly dead-bolting them. “We have read of such tragedies in distant places,” a resident of Utica said, according to one report, “but to think that we now have it at our doorstep!” And as the gory details of the killings began to spread, a stunned citizenry was left asking, as one local columnist put it, “What kind of human animal could do a thing like this?”

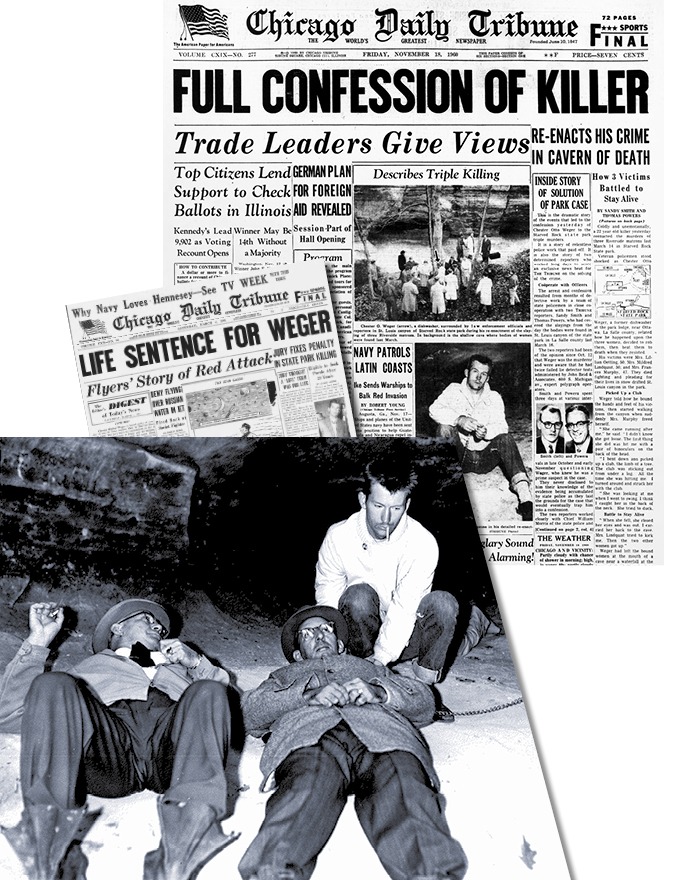

From the moment the three Riverside matrons turned up dead at Starved Rock, there was unusually intense pressure on investigators to find the killer or killers. The brute savagery and seemingly random nature of the triple homicide, the idyllic public setting of a state park, and the prominent social standing of the victims made the story catnip to the news media. The Associated Press even called the murders the “No. 1 news story in the world today.” To keep up with the great demand the influx of journalists and police was putting on the area’s communications infrastructure, Illinois Bell dispatched a mobile radio telephone car to the lodge and an emergency telephone trailer to downtown Ottawa. Life magazine would dedicate pages in two issues to the killings. The case made headlines for months in the Chicago Daily Tribune and the LaSalle County papers, whose readers were anxiously attuned to every development.

Amid the glare of the media spotlight — or perhaps in response to the scrutiny — no expense was spared. The LaSalle County authorities, including Sheriff Ray Eutsey and LaSalle County state’s attorney Harland Warren, insisted on heading up the investigation. But Governor William Stratton ordered the State Department of Public Safety, which included the state police and the Bureau of Criminal Identification and Investigation, to assist in what became one of the largest manhunts in the state’s history up to that point. “State officials,” the Tribune reported, “said that Sheriff Eutsey would get as many of the state’s 1,100 man force as he deemed necessary.”

The brute savagery and seemingly random nature of the triple homicide, the idyllic public setting of a state park, and the prominent social standing of the victims made the story catnip to the news media.

On the evening the women’s bodies were discovered, they were transported to Hulse Funeral Home in Ottawa, where in the small hours two pathologists from the Bloomington-Normal area conducted autopsies. Those who had observed the grisly scene of the killings that night could not have been surprised when the official word came back that the women had all died due to massive head trauma. One of the more puzzling findings was that the tip of one of Frances’s fingers was cut off and not recovered.

From a temporary war room set up inside Starved Rock Lodge, police commenced an interview blitz in the hunt for leads. Among the few hundred people questioned were all the employees and guests of the lodge; transients living in 17 motels in the vicinity; known fur poachers; a bakery truck driver seen near the canyon entrance the day of the crime; a man spotted in the park days before the killings, not long after he was arrested for chasing high school girls in Utica. Sheriff Eutsey even tracked down a traveling minister who had taken some motion pictures while driving through the park on the day the women were killed; the reverend turned over the films but they yielded nothing of substance.

In the search for clues at the crime scene, a weed burner was used to help melt snow, and a mine detector was brought in to locate anything embedded in the ground. Investigators put into evidence the women’s bloodied clothing, lengths of twine used to bind their wrists, and other trace items, including strands of hair and cigarette butts. They also found a three-foot-long tree limb coated with blood and hair; they surmised that the club — four inches in diameter and weighing roughly 10 pounds — was the main weapon. Additionally, they recovered three articles also encrusted with blood: a pair of binoculars, cracked into two halves; Mildred Lindquist’s Argus C-3 camera; and a camera case with a broken strap.

There was hope the women may have captured an image revealing the identity of the killer on the 35 mm color film inside the camera. After the film was developed, investigators’ attention immediately went to a triple exposure. One exposure featured a smiling Mildred posing in the foreground on the trail. The second showed Frances in front of the frozen waterfall. The third added an eerie dark blob near the left edge of the frame, which some investigators interpreted to be the shadowy outline of a man. Further analysis determined that the “mystery man” was nothing more than an optical illusion created by the outline of a canyon cave.

The Chicago companies that employed the victims’ husbands — Borg-Warner, Harris Savings and Trust, and Illinois Bell Telephone — offered a combined reward of $30,000 for information that led to the arrest and conviction of the killer. Nicholas Spiros, the lodge’s longtime operator, chipped in $5,000, bringing the total to the equivalent of more than $300,000 today.

Tips came flooding in by mail and telephone, but the bit of information that seemed most solid was furnished by a LaSalle auto dealer, who recalled that, on March 14 around 2 p.m., he was driving down Illinois Route 178, the road beside an entrance to St. Louis Canyon, when he saw a tan and beige Chevrolet Bel Air backing up to where three women stood. A young man got out of the car and began talking to the women. Another man stayed in the car. The dealer’s description of the first man: around 25 years old, 5-foot-8, 165 pounds, wavy reddish brown hair, dressed in a yellow-gray coat and blue pants that may have been denim.

Reviewing the evidence, the chief of psychiatry at Stateville prison provided investigators with a “sketch” of the type of person that could’ve committed the killings: a semireclusive man between the ages of 25 and 30, with a powerful physique, who may have been motivated to kill to gratify sexual urges.

But to the surprise of many, vaginal smears from the victims taken as part of the pathologists’ examination came back negative for the presence of sperm. This suggested that the women may not have been raped, as was initially assumed. The finding shifted the focus of the possible motive from sex to robbery, a shaky hypothesis supported in part by the crime lab’s claim that Lillian’s wedding band and engagement ring could not be found. Investigators began contacting pawnshops to see if the jewelry had been hocked.

“Many of our leads have led to dead ends,” a frustrated Eutsey told reporters in late March of 1960. “We’re going to solve this case. I don’t know where or how long it will be. But we will.”

Like all of the employees at Starved Rock Lodge, Chester Weger was interviewed by police in the days and weeks following the murders. The 21-year-old was a familiar, friendly presence amid the throng of busy lawmen. After the investigators moved their headquarters out of the lodge to one of the cabins on the property, they would sometimes ask for a pot of coffee or rolls, and every so often it would be Weger who would deliver the order from the kitchen. Weger was an avid outdoorsman, and he had extensive knowledge of the trails at Starved Rock. Since boyhood he cherished the feeling of peace and freedom he felt while walking through the woods, a sensation nearing communion with God.

Born in Derby, Iowa, in 1939, he was the only son among Herschel and Juanita Weger’s six children. When he was 2, the family moved to Illinois. They lived on the outskirts of Oglesby, near the Vermilion River, in a two-bedroom house without indoor plumbing. Weger slept on a pull-out sofa bed in the dining room. “I know now we were very poor,” says younger sister Mary. “Growing up, we never knew. We were just like the other kids, we thought.” Herschel worked seasonally as a painter and raised coonhounds, and Juanita for a time was a housekeeper at Starved Rock Lodge. The family truly lived off the land, eating only what meat they had hunted and growing vegetables in a large, plentiful garden. Being the only boy, Weger developed an especially close relationship with his father. In the woods behind the family house, Herschel taught his son to trap raccoons and mink, and how to skin the animals before hanging the pelts to dry.

In 1952, when Weger was 12 or 13, he was arrested on a statutory rape charge in Oglesby. The incident is mentioned in Illinois Prisoner Review Board documents, but the details have been redacted due to the ages of the people involved. Weger has claimed he got in trouble because he put a piece of white cloth inside the vagina of a girl who had been raped by someone else. “I was told to plead guilty,” he wrote in a prison autobiography that the Tribune reported on in 1963. “I did. I was given a pass.” In other words, he was placed on probation.

The discovery of that incident in Weger’s background first put the dishwasher on the investigation’s radar. During an early interview with police, Weger mentioned to state troopers that he knew of a shortcut out of St. Louis Canyon “up behind the falls someplace.” He offered to show the men the route if they felt it would be helpful. One trooper later testified that while they explored the area around the waterfall, Weger stopped, pointed up into a cave, and asked, “Is that where the women were lying?”

Less than a week later, the officers stopped Weger at the lodge to ask if they could accompany him to the apartment in LaSalle where he lived with his wife and two young children. They told him they wanted to take photos of him wearing his buckskin jacket, bedecked with leather fringe, like something from Davy Crockett’s closet. Weger consented. After snapping pictures, the officers clipped a couple of the tassels from the coat, which were sent to the Illinois Crime Lab in Springfield.

At this point, the Crime Lab had begun conducting polygraph testing in the courthouse office of State’s Attorney Warren. Even back in 1960 lie detector results were not admissible in court due to their unreliability, but authorities often used them to help guide an investigation. No less than two dozen subjects were tested. Weger underwent six tests. After each one, the examiner concluded he was not withholding any relevant knowledge and did not commit the murders.

In late April, with the triple homicide still unsolved, the Illinois Crime Lab came under intense fire for bungling the investigation. For weeks, the short-staffed and underfunded laboratory could not locate Lillian’s rings — until a deputy unpacking evidence found them in her glove. Another missing piece of evidence, Frances’s reading glasses, was discovered in the pocket of her jacket. The lab did not promptly report bloody fingerprints on the women’s clothing. It also allegedly misidentified hair found in Lillian’s hand as that of a female; a subsequent examination showed the source to be two males — one a youth, the other a middle-aged man.

The controversy would lead to the wholesale reform of the lab. But in the meantime, evidence in the Starved Rock case was forwarded to the Michigan State Police Crime Laboratory for reexamination. The detectives felt like they were back at square one. By mid-May the search for the Starved Rock killer had become the most extensive and costly manhunt in Illinois State Police history. All told, according to one Tribune report, state police had put in 21,360 total man-hours looking for the murderer. And where had it gotten them?

“We are no closer to the killer right now than we were on the day the bodies were found,” said Emil Toffant, chief of the state police’s Bureau of Special Investigations. “Hard work doesn’t mean a thing in a murder case. You have to catch the killer, and we haven’t done that — yet.”

Criticism of the investigation was perhaps felt most acutely by Warren, the state’s attorney. After all, it was he who had made the decision to send the material evidence to the Illinois Crime Lab, despite the state police’s preference for the FBI lab and facilities connected to police departments in Chicago and St. Louis. As the Starved Rock investigation ground to a relative standstill in the summer of 1960, the timing could not have been worse for Warren’s political prospects: An election loomed in early November, and his Democratic opponent was not letting voters forget that the most infamous crime in the county’s history remained unsolved, and that a killer still roamed free.

In late summer, Warren resolved to take matters into his own hands. The prosecutor became a detective. Taking stock of the evidence, which he had reclaimed from the Michigan lab, Warren focused his attention on the bloodstained twine used to bind the women. It made him curious what kind of cord was being used at Starved Rock Lodge. One September day, he went there to collect samples. In the kitchen, he located coils of what looked like similar twine. The discovery was enough to give the amateur sleuth the confidence that the killer was someone who had access to that kitchen.

In the interest of narrowing potential suspects, Warren set up a polygraph in a large cabin on the grounds of Starved Rock. He hired an examiner from John E. Reid & Associates, the Chicago firm that would soon popularize the Reid Technique, a method of interrogation based on psychological manipulation that is still widely used by law enforcement and has been known to elicit false confessions. After several employees were tested, the next up was Weger, who had left the lodge in May and found work as a painter. When the test was complete, Weger exited the cabin. As legend has it, the examiner looked at Warren and uttered some variation of “He’s your man.”

More than six months after the murders, Weger had become the investigation’s prime suspect.

Early in the morning on September 27, LaSalle County sheriff’s deputy William Dummett and assistant state’s attorney Craig Armstrong picked up Weger outside his father’s home in Oglesby and took him to the Reid headquarters in Chicago. It was late morning when John Reid himself sat down across the table from Weger. Over the course of the next two to three hours, Reid discussed the Starved Rock case with him and administered a polygraph test. When Reid concluded Weger was being misleading, he spent hours trying to persuade him to tell the truth. But despite the pressure exerted, Weger maintained he had nothing to do with the killings.

Into the afternoon and evening, Reid and an assistant continued to interrogate the young man. During one test, Weger would later testify, Reid instructed him to answer “yes” to every question, including ones about the murders. He refused. At another point, Reid threatened to inject Weger with truth serum.

Weger finally left Reid’s office sometime around midnight. But the interrogation did not end. In the front seat of Dummett’s Chrysler, with Weger sandwiched between the deputy and Armstrong, Dummett told Weger if he did not sign a confession, he would be sentenced to the electric chair.

“Chester,” Dummett said, according to Weger, “you are going to ride a thunderbolt.”

“I’m not going to go to the chair,” Weger replied, “because I didn’t kill anyone.”

Dummett would later deny making the threat, but on the stand Armstrong refuted his statement, saying that the exchange had indeed occurred.

It was around 2 a.m. when Dummett’s Chrysler pulled into the parking lot at the LaSalle County Courthouse. Up in his fourth-floor office, Armstrong put Weger through four more hours of questioning. Even as Weger continued to protest his innocence, he was by all accounts polite and agreeable. He assented to Armstrong’s request to take off his shirt so that the assistant state’s attorney could take photos of his build, as well as his tattoo: “Rocky,” a nickname, on his left arm. He also complied when Armstrong then asked him to appear in a police lineup. The 21-year-old was photographed standing with prisoners from the county jail, not one of whom appears to be under the age of 40, one of Weger’s lawyers would later point out.

As daybreak approached, investigators told Weger they wanted to obtain certain items of his clothing, which would be sent off to an FBI crime lab. He consented. It was about 7 a.m. when Armstrong and deputy Wayne Hess drove Weger back home. Inside the modest apartment, Weger brought out the buckskin jacket they had requested. Armstrong then asked if he and Hess could look through the place. Weger said yes. The assistant state’s attorney began opening drawers and cupboards, looking for string; he found several pieces, but it was very fine, nothing that matched the thicker cord found at the crime scene.

Finally, Armstrong and Hess drove Weger to his father’s house in Oglesby, where he had been staying. During the ride, Weger began to nod off. For more than 24 hours he had been kept awake while enduring on-and-off interrogation. And for 24 hours he’d maintained that he had not killed the three women.

Soon after that, Warren and Eutsey asked the state police to put Weger under 24-hour surveillance. The stated reason was public safety. But the round-the-clock tail may have actually been part of a broader strategy by Warren to intimidate Weger into confessing. Evidence for this notion came to light in 2009, when Warren’s daughter, Anne Warren Smith, who had been employed as her father’s legal secretary from 1981 until his death in 2007, signed an affidavit attesting to the veracity of a handwritten note she discovered while sifting through the former state’s attorney’s documents. Scrawled on two pages of undated yellow paper was what appeared to be a plan to frame Weger. The affidavit included a transcription: “Query — how do you prove Weger was present,” the note begins. “Get Man to confess, persuade Him. What do you do. States Attn. Sheriff’s office. Commence Psycological [sic] warfare A. Put tail on him night + day that visible, know [sic] being followed. B. Intense investigation of background. Focus on one man. […] Plan pick him up 5:30 or 6pm Have […] two deputies take him Up 5th floor started interrogating 15 hour there.”

In mid-October, a rotating detail of eight state troopers began surveilling Weger night and day. The officers lurked in a car outside his apartment. They followed him to taverns and a bowling alley. They would show up to his painting job sites and take photos of him. When he went to paint a steeple in the nearby town of Peru, they sat outside the church watching him.

Weger had been surveilled nonstop for a month when, on November 16, 1960, around 6 p.m., Dummett and Hess picked him up at his apartment. At the courthouse, the deputies sat Weger down and began asking him, once more, about his involvement in the Starved Rock murders. Again, he told them he didn’t kill anyone.

During the interrogation, Sheriff Eutsey went to a justice of the peace — a local grocer named Louis Goetsch — to get warrants for Weger’s arrest. This was highly unusual, one of Weger’s lawyers would later argue. Justices of the peace typically presided over marriage ceremonies, their jurisdiction limited to misdemeanor cases. In a felony matter such as the triple homicide, where the possible punishment was death, a circuit judge would typically have been the proper authority to determine if there was probable cause for arrest.

What evidence did the authorities have at this point? There was the similarity of the common twine in the lodge kitchen to that found wrapped around the women’s wrists, though investigators could find no expert to testify that they were identical. There was Weger’s buckskin jacket that he had worn for years before the killings and for several months afterward. Investigators had sent it to an FBI lab, which concluded it contained small droplets of human blood, though the blood was present in such a minuscule amount it was not able to be type matched to Weger or any of the women. There were also some lodge employees who had begun to recall having seen scratches on Weger’s face in the wake of the murders, though neither they nor the officers who questioned Weger initially had reported such marks earlier.

At around 9:30 p.m., Weger was informed of the charges against him, which included the three murders at Starved Rock, as well as charges stemming from two other incidents in Matthiessen State Park: a robbery in July 1959 and a rape-robbery in September 1959. The victims in those cases, Weger was told, had picked him out of the lineup he had cooperated in earlier. He would never be tried in those cases.

Back on the third floor, the deputies continued interrogating Weger. It was at this point in the night, Weger would later testify, that Dummett essentially gave him two options: Confess, get a life sentence, and be released within 14 years. Or don’t confess and be executed.

At 1 a.m., Eutsey brought in Weger’s wife and parents to talk to him. Herschel Weger testified that the sheriff took him aside and told him if his son didn’t confess, he would go to “the little green room,” which he interpreted as a reference to the electric chair. Herschel said that, standing outside the interrogation room, he could hear Dummett say to his son repeatedly, “You know you did it. Why don’t you come clean and say you done it? Why do you want to treat your wife and children like that and why do you want to treat your father and mother like that? Come clean and tell us about that.”

Herschel would testify later that he was then sent into the room to talk to his son. He asked Chester if he had committed the murders. Chester looked at his father and said, “No, Daddy, I did not.” Herschel then asked Eutsey to hold off on interviewing his son until he could secure a lawyer the next day. The sheriff ignored his request. Before Weger’s family departed the courthouse, his wife kissed him. His mother hugged him and said he should tell the truth.

Shortly before 2 a.m., after being interrogated for the better part of eight hours, Weger looked over at Dummett and Hess. “All right,” he said, according to his testimony. “If you want a confession, I’ll give you one.”

Weger then proceeded to give police a version of events that had him trying to rob the three women when things got out of control. In his confession, which he gave to no less than four officials over the next 15 hours, here’s how he said the episode unfolded:

During his afternoon break from work, he was walking toward St. Louis Canyon when he encountered the women. He grabbed a strap from one, believing it to be a purse, but it was attached to the binoculars. The strap broke. At this point, he said, one of the women hit him with either the binoculars or a camera. Another attacked him with something sharp, perhaps a comb. Then, somehow, he was able to calm the women and persuade them to walk into the canyon as he followed. He told them that once they returned to the canyon he would let them go. Back in the canyon, the women agreed to allow him to tie them up. He used string from the kitchen that he had in his pocket. He stole nothing from the women and began to walk away. That’s when one of the women broke out of her binding and attacked him. He picked up a tree branch, knocked the woman unconscious, and dragged her body into a cave. Fearing that he had killed her, he then bludgeoned the other two to death to eliminate witnesses. Then the woman he first hit regained consciousness and struck him with the binoculars. He retaliated with the tree limb and the binoculars. Overhead he spotted a red and white Piper Cub airplane and worried it was a police plane. So he dragged the bodies of the other two women into the cave. “Then I took this here lady’s coat off, if I am not mistaken,” Weger said, “and put in front of this one here and just made it look like rape, is all I can say.” Asked whether he removed one woman’s pants and stuck them under her underskirt, as was the case at the crime scene, he said, “I do not know.” He checked their pockets for money and, finding none, left the scene. He washed the blood off his hands in a creek or in the snow, then returned to the lodge to work his evening shift.

On the morning he confessed, around 3 a.m., Weger was brought to the county jail. Four and a half hours later, he was taken in shackles to St. Louis Canyon, where he reenacted the crime as described in his confession for an audience of law enforcement officials and news media.

Two days later, while in jail discussing his case with his court-appointed public defender, Joseph Carr, Weger recanted his confession. “I wasn’t even there,” he told Carr. “I don’t know anything about the murders.” The statements he gave to officials, he claimed, were informed by details given to him by Dummett, including photographs of the crime scene the deputy showed him, as well as newspaper reports and talk he’d heard around the lodge.

The following month, a judge denied Weger’s pretrial motion to suppress his confession. Coerced or not, his own words would be the state’s most powerful weapon against him.

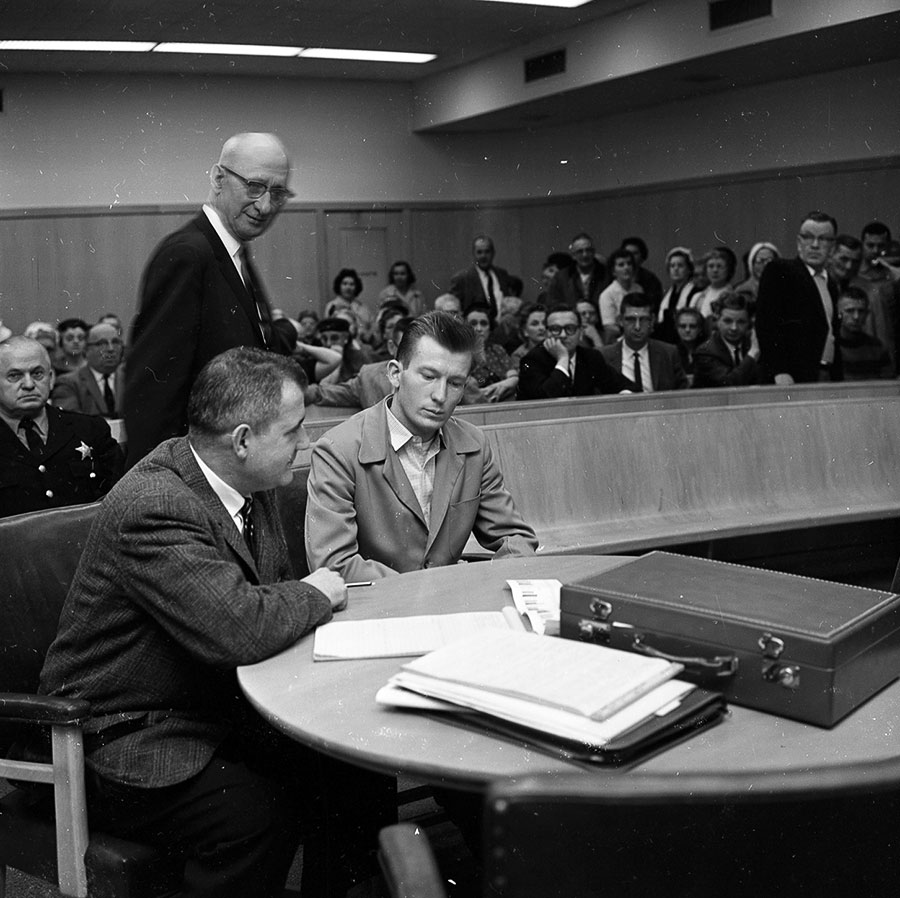

The trial began in February of 1961 at the limestone county courthouse in downtown Ottawa, a couple of blocks from the park where Lincoln and Douglas held the first of their historic debates. On the first day of testimony, the courtroom’s 100 seats were filled, with dozens of other curious members of the public standing against the walls. Trying the case in front of Circuit Judge Leonard Hoffman was newly elected state’s attorney Robert Richardson, a rather green trial attorney given the office he held. As his first assistant, Richardson tapped Anthony Racugglia, a brash 27-year-old Illinois Valley native fresh out of John Marshall Law School who had never before tried a murder case. In the absence of eyewitnesses or physical evidence that definitively tied Weger to the crime, the prosecutors made his confessions the bedrock of the state’s case. On those grounds, they would stand in front of the jury of seven women and five men and ask them to sentence him to death.

Privately, though, the prosecutors held doubts about the integrity of Weger’s statements. “I read that confession one night as we were preparing this case,” Raccuglia would later recall, in 2010, during an Illinois Institute for Continuing Legal Education (IICLE) event about the Starved Rock murders. “I said, ‘Bob, this can’t have happened this way. This is absolutely ridiculous to have happened this way.’ He said, ‘Well, what are you going to do about?’ I said, ‘Well, nothing — I’m going to tell the jury this is what happened. Because, bottom line, at the end of the confession he says, “I killed ’em.” That’s what we need. We need him to admit he killed the women. Not how he did it.’ ”

Richardson and Raccuglia decided to prosecute Weger for the murder of Lillian Oetting only. Their thinking was that, were they to lose, they would be able to then try him for the deaths of the other two women. “I was concerned about the confession. And I wanted to test that confession with the judge and with the jury,” Raccuglia explained to the IICLE event audience. “It was a risk because without the confession all we really had was the spattered jacket and the circumstance of the scratches.”

Defending Weger was a Marseilles attorney named John McNamara, himself a former LaSalle County assistant state’s attorney whom Weger’s father hired with the proceeds from the sale of two coonhounds. In his closing argument, McNamara took direct aim at deputy William Dummett. “The only bit of evidence as to how [the murder] might have happened are the confessions that have been placed in evidence of Chester Weger, which have been denied by him,” McNamara told the jury. “Every word of that confession shows it was a cunningly devised lie. A lie first mouthed by William Dummett, after which he offered Chester Weger his life if Chester would confess according to his theory.”

After deliberating for less than two days, the jury found Weger guilty of murder and sentenced him to life in prison. The verdict happened to come down on March 3, Weger’s 22nd birthday. Newspaper headline writers had their fun with the coincidence: “Weger Gets Life as Birthday Gift.” Members of the jury later explained they chose a life sentence instead of the death penalty because they saw it as a greater punishment for an outdoorsman. Weger would not become eligible for parole until 1972.

As Weger was ushered out of the packed courtroom, the mass of people in the gallery moved suddenly forward to get a closer look at the man they could now openly call a killer. Escorted into a conference room, the newly convicted man was overwhelmed by the whir of TV cameras, the pop of flashbulbs, reporters shouting questions.

“Chester, do you still think you were framed?” one newsman asked.

“I know I was,” Weger replied.

“You said people lied about you. What were these lies?”

“They will come out in time.”

During the early days of his imprisonment, Weger remained confident he would soon be released. In his mind, there was no way that what he viewed as a grave injustice would stand. But days became months, months became years, and years slowly slipped into decades. A couple years into Weger’s sentence, when the reward money in the case was distributed, State’s Attorney Warren accepted $11,500, and deputies Dummett and Hess each took $5,000. Six years in, Weger confided in his wife, Jo Ann, that she would be wise to move on with her life. She filed for divorce. By the mid-1970s, Weger’s postconviction options had all but dried up. His case had been in front of the Illinois Supreme Court twice, first in 1962 and then in 1971. In 1977, his request for a hearing before the United States Supreme Court was denied.

Even as he explored every legal avenue to get out of prison, Weger was adapting to life behind bars. He almost always worked a job, from line cook to dispenser of art supplies. He mastered the trade of bookbinding and rose to the position of instructor in the inmates’ bindery. He acquired vocational skills in bookkeeping, clerical duties, and inventory control. He taught himself to paint using oils, often depicting the wooded landscapes of his youth that he so missed. He read voraciously: history and philosophy and magazines and the Bible, always the Bible. In 1985, after being sent to prison with an eighth-grade education, Weger attained his GED.

But hearing after hearing, year upon year, the Prisoner Review Board would deny his parole. It didn’t help Weger’s case that, each time, Anthony Raccuglia, one of the prosecutors, would write an impassioned letter arguing against release. Up until his death in 2019, Raccuglia would sometimes even make the 130-mile drive from LaSalle, where he maintained a private practice, to Springfield to read his letter aloud before the board. “If Chester Weger is paroled, it will lend credence to his continued argument that he is innocent,” he wrote in 2012. “He deserves to die in prison, and he deserves to have his body delivered to some cemetery somewhere to begin its journey to hell where without question he will have a very prominent role.”

Around the turn of the century, Weger began taking an interest in stories about how DNA testing was being used to exonerate the wrongfully convicted. The emerging forensic technology began to look to him like his best chance of freedom. The Illinois Appellate Defender’s Office soon appointed Weger a new public defender, Donna Kelly, a meticulous and dogged attorney who would quickly become one of Weger’s fiercest advocates. It took only a reading of the transcript from the 1961 trial to convince Kelly that not only did Weger’s claims of innocence have merit but that he had been the victim of numerous injustices during the investigation.

In April 2004, Kelly filed a motion requesting DNA testing on various items of evidence collected at St. Louis Canyon in 1960. The LaSalle County state’s attorney’s office fought the motion, filing a response that said items may have been contaminated in the more than 40 years that they had been stored.

An assistant state’s attorney named Brian Towne was tasked with looking into the history of the care of the evidence. A friend and protégé of Anthony Raccuglia who would go on to become the county’s top lawyer, Towne talked to any official who may have had custody of the evidence over the previous four decades. What he discovered was catastrophic for Weger’s request for DNA testing.

After the trial concluded, the evidence had been placed into a filing cabinet, the victims’ bloody clothing intermingled with Weger’s clothes. Raccuglia told Towne that the state’s attorney’s office allowed “numerous groups of individuals, including many high school classes, to view the physical evidence as part of class trips or citizen’s tours.” The evidence would be put on display and “any individual within the group that wanted to pick up the evidence, look at the evidence, or examine it in some fashion were allowed to do so without the presence of gloves or any other protection against contamination.” Raccuglia estimated that hundreds of people had come into contact with the evidence.

In July 2004, Kelly withdrew the motion for testing and pivoted to a new quest: seeking a pardon for Weger from then-governor Rod Blagojevich. In the 50-page clemency petition she filed in 2005 she attacked the confession as “wholly implausible” on a number of fronts. Weger frequently used tentative language, such as “I think” and “I don’t know,” during critical moments in his recollection of the crime. He also got key details wrong, and later signed off on multiple corrections to the confession transcript that she argued seemed coached by deputies to fill in discrepancies. On top of that, the narrative Weger offered seemed far-fetched, Kelly argued: “Chester’s confession has him, though unarmed, convincing the women — who have retained possession of the camera and binoculars — to go back down into the canyon upon his promise to release them,” she wrote. “It is completely contrary to human nature that three women — two of whom had purportedly turned on their aggressor by striking him — would now suddenly become complacent and agree to return to a cold, snowy, canyon area surrounded by 80-foot sheer rock walls, because they are fearful of an unarmed man.”

Kelly also cited in the petition a 2002 story in LaSalle County’s NewsTribune in which Raccuglia made a stunning admission: The prosecution withheld evidence that Lillian Oetting was sexually assaulted, so as to avoid undermining the robbery motive of Weger’s confession. And Kelly outlined two cases of significant investigative misconduct in Deputy Dummett’s background, which she argued added weight to Weger’s claims that he’d been coerced into a confession.

The most curious element of the petition, though, was an affidavit from Weger in which he amended his alibi for the afternoon of March 14, 1960. At trial he had testified that during his afternoon break from work that day he was in the basement Pow Wow Room of Starved Rock Lodge writing a letter, tending the furnace, playing pinball, and listening to music on a jukebox. Now, suddenly, he said a friend and busboy at the lodge, Stanley Tucker, drove him into downtown Oglesby, where he got a haircut. The petition also included an affidavit from the barber, Ben Franklin, in which he swore Weger was in his barbershop that day.

Why was he just now providing a verifiable alibi? According to Weger, when investigators originally asked him for his whereabouts during the time frame of the crime, he told them of hitching a ride with Tucker to Oglesby. Later he felt pressure to fabricate an alibi after police informed him that Tucker — himself a suspect — was no longer corroborating his story.

In the affidavit, Weger also claimed for the first time that, during the interrogation before his confession, Dummett held a gun to the side of his head and pulled the trigger, and Eutsey hit him in the stomach and groin with a billy club, a flashlight, and shackles.

As for the biological evidence found at the crime scene, Kelly argued that it pointed away from Weger. Buried among thousands of pages of case documents, she came across a Washington University laboratory report from November 1960. It contained the results of tests on hairs, including those found in the glove of Frances Murphy. The lab concluded none matched that of Weger. But the jury never heard that evidence.

Governor Blagojevich denied Weger’s petition in 2007. But all was not lost. The revelations Kelly had uncovered touched off widespread reconsideration of the case and a groundswell of public support for Weger’s claims of innocence. Several years ago, the Illinois Innocence Project out of Springfield briefly took up the case. In 2016, Nancy Porter, the last living juror from the trial, told the Tribune she now found Weger’s confession implausible — it was unlikely, the then 92-year-old felt, that an unarmed man of Weger’s slim build could overpower three women.

David Raccuglia, the son of prosecutor Anthony Raccuglia, began to question the belief instilled in him since childhood that the man his father convicted was akin to the boogeyman. “When I was a little kid, I was terrified of Chester Weger,” says Raccuglia, 62, the founder of the men’s grooming company American Crew. “My grandmother told me when I was 5 that if Chester were ever to get out of prison that he would come hurt me and my family.”

But following the clemency petition, he says, “I started listening to Donna Kelly’s side of the story for the first time.” He decided to embark on a sort of fact-finding mission of his own. He read the trial transcript and other case documents. He also began a correspondence with Weger, eventually asking if he could meet him in prison. The two men struck up an unlikely friendship. Raccuglia soon began filming interviews with Weger, with a mind toward making a documentary. He amassed dozens of hours of footage, some of which was incorporated into a docuseries, The Murders at Starved Rock, about the case and Raccuglia’s own conflicted journey to find the truth, which premieres December 14 on HBO.

Like Raccuglia, I grew up in the Illinois Valley. And for much of my childhood in a one-stoplight town 15 miles west of Starved Rock, I saw Weger as something of an apparition, a symbol of fear. When I was 10, maybe 11, years old, I went to the library and borrowed the urtext about the killings: The Starved Rock Murders, a peculiar little paperback self-published in 1982 by local newspaper reporter Steve Stout, who has been outspoken about his belief in Weger’s guilt ever since. I had no idea such violence had ever visited the park where I’d gone on so many school field trips, where family members had gotten married. Twenty-five years later, while flipping through 1960s newspapers on microfilm at local libraries, I would often come across a front-page headline about a development in the Starved Rock investigation followed a couple of pages later by an ad for Malooley’s, the grocery store my grandfather ran with his brothers, touting pork butt roast for 39 cents per pound.

One recent afternoon, I called my 85-year-old uncle, Ronald Malooley, who worked at that store as a child. I wanted to know what he remembered about the mood of residents in the area in the wake of the murders. He paused, inhaled deeply, and told me something he’d never shared before. As a teenager in the early 1950s, he had talked his way into a job on a crew of “gandy dancers,” meagerly paid railroad laborers who made repairs to the track, replacing rotted crossties and leveling the grade. One hot summer day, a scrawny, pale-faced kid showed up to work. He introduced himself as Chester Weger and immediately took his shirt off. The next day, he came to work with the worst sunburn my uncle had ever seen. “I always thought he was a little off base. There was, I don’t know, no moxie. He was an outsider,” my uncle told me. “But far be it for me to say he seemed like a murderer.”

In the 16 years since the clemency petition, one of the most noticeable side effects has been the spread of alternative theories of the Starved Rock murders. Kelly’s inquiry pointed out the lack of incontrovertible evidence against Weger — and that vacuum has been filled by armchair investigators eager to forward other potential suspects and scenarios. Some raise an eyebrow at the juvenile offenders who discovered the women’s bodies. Why had the boys found the crime scene so soon after the search commenced? Others share images of old news stories about a LaSalle County man who was known to stash stolen guns in a cave at Starved Rock before they would be fenced in Chicago. Had the Riverside wives, during their hike, stumbled upon something that they weren’t supposed to see?

Still others believe the killer was someone the victims knew intimately. They point to a report by William Jansen, a 25-year-old graduate of the Michigan State School of Criminology, who state police brought in to take a fresh look at the case when they’d hit a dead end. Jansen concluded that the murders appeared to be “more a revenge crime than a sex crime,” and recommended friends, family, and business associates be questioned.

With the petition, Kelly herself had cast suspicion on another man: George Spiros, son of the operator of Starved Rock Lodge at the time of the murders. Spiros lived with his father in a house on the park grounds, not far from where the women were found dead. His alibi didn’t quite check out, but he passed a polygraph. In May 2005, two weeks after Kelly presented her findings for a panel of Prisoner Review Board members advising the governor, the 73-year-old was found dead in his Starved Rock residence. The apparent cause was a self-inflicted gunshot wound. “I feel it’s suspicious that this man was a suspect in this highly publicized case,” Kelly told the Times of Ottawa, “and now he’s dead.”

The petition included even more red meat for wannabe detectives: an affidavit from a Chicago police officer describing a deathbed confession. Mark Gibson said he and his partner were dispatched to Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Hospital on the Near West Side in 1982 or 1983. When they arrived, a nurse told them that a woman dying of cancer wanted to “clear her conscience.” She grabbed Gibson’s hand, telling the officers that when she was younger, she had been with friends at a state park near Utica, Illinois, when “something happened,” “things got out of hand,” and “they dragged the bodies.” Before the police could get more details, the woman’s daughters arrived and yelled at the officers to leave, saying their mother was “out of her mind.”

It would not be the only deathbed confession associated with the Starved Rock murders. In 2008, the first meeting of the Committee to Free Chester Weger was held at the Reddick Library in Ottawa. Founders Robert Petre and David Marsh bonded over their research into the case. They began sending their findings to the Prisoner Review Board, attending Weger’s parole hearings, and holding public rallies calling for Weger’s release. In 2013, before Weger’s 18th hearing, Marsh posted to the Starved Rock Murders Facebook page an interview with an Illinois Valley woman named Alice Wrona Boehm, the sister of the late Harold “Smokey” Wrona, a convicted felon of some local notoriety. Before he died in 2005, Boehm said, Wrona told her he was involved in the murders and that Weger had nothing to do with the crime.

As an outlet for sharing her own extensive research into the case, Cathy Carroll launched the Friends of Chester Weger Facebook page in 2013. Even though she had grown up in LaSalle County, Carroll knew next to nothing about the Starved Rock murders before falling down the rabbit hole. The 58-year-old Wheeling resident suspects the Riverside women may have been the victims of a mob hit. She points to their husbands’ close association with Virgil Peterson, who as the head of the Chicago Crime Commission was trying to stamp out organized crime. At the time the women were killed, LaSalle County had a well-earned reputation as a haven for Mafia-connected vice, particularly illegal gambling.

Several years ago, Carroll began a correspondence with Weger. In one reply letter, he thanked her for the Christmas card and book she’d sent him. He praised the wisdom of Plato and Kant, and offered some deep, if cryptic, thoughts on Christian theology. He seemed preoccupied with lies and liars and ignorance. He cited Jeremiah 5:21: “Hear this, you foolish and senseless people, who have eyes but do not see, who have ears but do not hear.”

Embedded among the eight pages of neat penmanship was one of the only sentences that directly addressed his case. It said he had been framed for the murder of Lillian Oetting. And it seemed to Carroll to be a message Weger hoped people like her would continue to share to the world, the one far beyond the walls of his prison cell.

Four years ago, Andy Hale made the 300-mile drive from Chicago to Pinckneyville Correctional Center to introduce himself to Chester Weger. The attorney had recently read a newspaper item about the Illinois Prisoner Review Board denying Weger’s parole for the 21st time. He knew next to nothing about Weger or the Starved Rock murders, but he was compelled by the story of a prisoner who, after more than 50 years behind bars, staunchly refused to admit guilt — even in the interest of securing release. “I was just so impressed by that persistence,” Hale says. After talking with Weger about the case and doing some research, he became convinced that the man had been wrongfully convicted. It wasn’t long before he began work as Weger’s pro bono lawyer.

In some ways, Hale was an odd choice to represent Weger. In the middle of the aughts, the City of Chicago began hiring him as outside counsel to defend Chicago police officers in civil rights matters, including police brutality and wrongful conviction lawsuits. Some of those suits were filed by Black men who alleged they were tortured into false confessions by officers under the watch of notorious Chicago police commander Jon Burge.

But by the time he met Weger, Hale had started representing the other side of such cases too. In 2014, he produced and appeared in a documentary, A Murder in the Park, about the wrongful conviction of Alstory Simon, who was exonerated after spending 15 years in prison for a 1982 double murder in Chicago’s Washington Park. The film centered on the role the Medill Innocence Project at Northwestern University played in railroading Simon in its quest to exonerate a death row inmate named Anthony Porter. For a time, Hale helped represent Simon in the exoneree’s $40 million lawsuit against Northwestern, which eventually was settled for an undisclosed amount. Hale had also taken up the case of Cleve Heidelberg, who had been convicted of killing a Peoria County police officer during an attempted robbery of a drive-in movie theater in 1970. Thanks to Hale’s investigative efforts, Heidelberg’s conviction would eventually be vacated after 47 years. “Because I spent all these years defending police officers, I was uniquely qualified to analyze cases like this, dig in, and make some progress,” Hale says. “I know what evidence should be there. I know what police are supposed to do.”

Delving into Weger’s case in the fall of 2017, he tapped a lawyer at his firm named Celeste Stack to assist. A former prosecutor with 30 years under her belt in the Cook County state’s attorney’s office, Stack specializes in cases involving DNA testing, particularly those in which a person convicted before the rise of modern forensics is asking for evidence to be reexamined. This, she and Hale quickly realized, was where they needed to focus their effort to exonerate Weger. “As we got more documents and got to know the case, it evolved into our belief that this is certainly a wrongful conviction,” Stack says. “Our hope was that there was still evidence around that could help us prove that with forensic testing.”

To show the evidence in Weger’s case still could yield probative information if tested, Hale and Stack needed to find a laboratory that would be undaunted by the challenge of reviewing items that were more than a half-century old and had been stored improperly and manhandled for decades. They didn’t have to look farther than the northwest suburbs. Microtrace, based in Elgin, specializes in the analysis of trace evidence: hair, fibers, dust, soil, paint, glass — any material that can be inspected under a microscope. The lab has a reputation for doing a lot with a little and coming up with fresh approaches to cases that had stumped other investigators. Its résumé includes work on some of the highest-profile cases in the last 30 years: the Unabomber, the Oklahoma City bombing, JonBenét Ramsey, the Green River Killer.

Hale reached out to Microtrace founder Samuel “Skip” Palenik, a forensic microscopist who often quotes Sherlock Holmes and whose horseshoe moustache gives him the air of a police detective. When the attorney mentioned his client was Chester Weger, Palenik was floored. The Starved Rock case, he explained, had inspired him to go into his line of work. Raised on the Southwest Side, near Midway Airport, Palenik was an intellectually curious 13-year-old when the triple homicide began dominating the front page of his parents’ Chicago Sun-Times. Reading about the latest details of the investigation over breakfast every morning, he became entranced with the notion that he could put the clues together to solve the high-profile whodunnit. Now in his 70s and nearing retirement, Palenik was tickled by the poetic symmetry that his career might be capped off by some small contribution to the case.

“As we got more documents and got to know the case, it evolved into our belief that this is certainly a wrongful conviction,” says one of Weger’s attorneys.

In August 2020, six months after Weger’s release, Hale and Stack filed a petition in LaSalle County Circuit Court pushing for forensic testing. Circuit Judge Michael C. Jansz questioned the chain of custody on those items. So too did Colleen Griffin, an assistant state’s attorney from Will County, who was brought in as special prosecutor after LaSalle County state’s attorney Todd Martin recused himself, citing a professional conflict.

Their concerns were based on the mishandling of the evidence that had been exposed during Weger’s initial DNA testing bid. When Donna Kelly, his lawyer at the time, withdrew her motion in 2004, she made comments in court that portrayed the evidence chain of custody as “completely unreliable.” Now her words were being used against Weger’s new team to challenge their request.

To answer those concerns, Hale and Stack turned to Microtrace’s Palenik and his son Christopher, who followed his father into the family business. The Paleniks looked at the inventory report created in 2004 and said it seemed to include items of evidence that were intact, identifiable, and suitable for forensic testing. They pointed out other cases where Microtrace was able to recover evidence from such rough-looking items as broken microscope slides. And in the 16 years that followed Weger’s first effort to have the evidence tested, forensic techniques had evolved. Mitochondrial DNA analysis, for instance, can now be done on degraded samples many decades old by allowing the extraction of genetic material from hair shafts; earlier techniques required the root. But the only way to know for sure if The People v. Weger’s rickety file cabinet of evidence still had value, the Paleniks concluded, would be to allow Microtrace to do its own preliminary examination of it.

This past June, in an Ottawa courtroom less than three miles from where Weger was tried, his team made its case. “Girl Scout Troop 205 has had more access to the evidence than me,” Hale said. “I haven’t seen the jacket. There’s kids that have tried the jacket on.” As he paced in front of the judge’s bench, he bent down, picked up a trash can and held it aloft. “The state wants to make it sound like all the evidence is in this garbage can, and it’s been jumbled up, and it’s completely worthless. If I take out of the garbage can the slide of the hair on Mrs. Murphy’s glove, despite it being in the garbage can, Mr. Palenik can test it. And we can test it, and it will have forensic value — huge forensic value. It could solve the whole case.”

The judge agreed to let Microtrace take a look — not a full-on DNA analysis, which if approved would be performed by a company specializing in genetic testing, but a big first step in that direction. And by the end of that month, the LaSalle County sheriff’s office had produced the file cabinet from an evidence room. Weger’s team and Microtrace spent two six-hour days cataloging every piece of evidence, some 313 unique exhibits. In the top drawer, they found four pairs of Weger’s blue jeans. The bottom drawer contained a cloth sack with Weger’s buckskin jacket commingled with Lillian’s clothing still marked with brownish blood stains. Some key evidence was missing, including the clothing of Frances and Mildred, as well as all three suspected murder weapons — the tree branch, the camera, and the binoculars.

They were thrilled to discover that much of the trace evidence, such as hair and fiber samples, were in good condition, preserved and mounted under labeled glass slides in specially designed wooden boxes — as useful scientifically 60 years later as the day they were made. “Those glass slides were engraved with a diamond-tipped pen on the glass to tell you exactly what is there,” Hale excitedly reported to Judge Jansz at a status hearing in July. “We think the evidence was, frankly, just stunningly remarkable.” Weger’s team narrowed its request for DNA analysis to nine items. Among them: hairs from Lillian’s left-hand fingers and right-hand glove, string found in the cave, and four cigarette butts from the scene.

In late September, Weger appeared in a LaSalle County courtroom for one of the first times since he was sentenced in 1961, to hear the judge’s decision on whether those items could be tested. Over the summer, his nieces had found him a rental house in LaSalle, a modest two-floor white cottage with gray shutters on a corner lot. He was not given a warm welcome in the local press. His return occasioned a front-page photo of his residence in the NewsTribune beside the all-caps headline: “NEW NEIGHBOR.” Outside the courthouse before the hearing, Weger sat in a wheelchair surrounded by Hale and family members. He was wearing bright white New Balance sneakers, a short-sleeved golf shirt, and gray sweatpants, with a fleece jacket thrown over his lap like a blanket. Thin plastic tubes from an oxygen tank ran into his nostrils, and a catheter peeked out the bottom of his right pant leg, next to an electronic ankle monitor.

“Today is a big day for us,” Hale said to the group. “The culmination of a couple years of work, and 60 years of Chester fighting to clear his name. Justice will be served by letting us proceed with the forensic inspection of this evidence. And Chester, your spirit is with us today. You’ve never given up the fight. And I know you’ve been looking forward to this day in court. You’ve fought for almost seven decades to clear your name. And I think that’s one of the reasons you’re still alive.”

Related Content

In the end, Jansz said he needed more time to consider the issue, and in late October, Weger was once again wheeled into court. This time the judge was ready to rule. He approved DNA inspection on eight of the nine exhibits. In early December, a representative from Microtrace watched as sheriff’s deputies packaged the evidence and sent it off to Bode Technology, the nation’s largest private forensic DNA lab, in Virginia. Results could be disclosed as soon as February 8, the date of the next hearing in the case.

If Weger’s DNA is not found on any of the items, Hale says he and Stack will argue that the conviction should be vacated. The results may also reveal a profile that matches another suspect, perhaps someone whose genetic information is stored in the FBI’s database. In any case, if the testing ultimately excludes Weger as the perpetrator, a judge could decide to exonerate him immediately. But more likely a decision wouldn’t come until after months, even years, of hearings — the kind of time that Weger and his family worry he may not have left if his health deteriorates.

As the judge finished reading his ruling, Weger sat stoically in his wheelchair. At that moment, he had never been closer to potentially clearing his name — and yet he appeared unmoved. It was the look of a man who seemed to understand that, even after surviving nearly 60 years in prison, his toughest fight had only just begun.