You need to try the banosh,” said Elizabeth, our Ukrainian friend. “This is something typical from the west.” The menu described the cheesy porridge as “Carpathian grits,” and I was sold, having never met a grit I didn’t like.

My wife and I met Elizabeth (anglicized from Yelyzaveta) through friends of friends in the spring of 2022, shortly after she fled Kharkiv at the start of the war and settled in Chicago. She lived briefly in our garden apartment. We kept in touch with her and could think of no one better to invite to Anelya, the new Ukrainian restaurant from Johnny Clark and Beverly Kim, the husband-and-wife team behind Parachute.

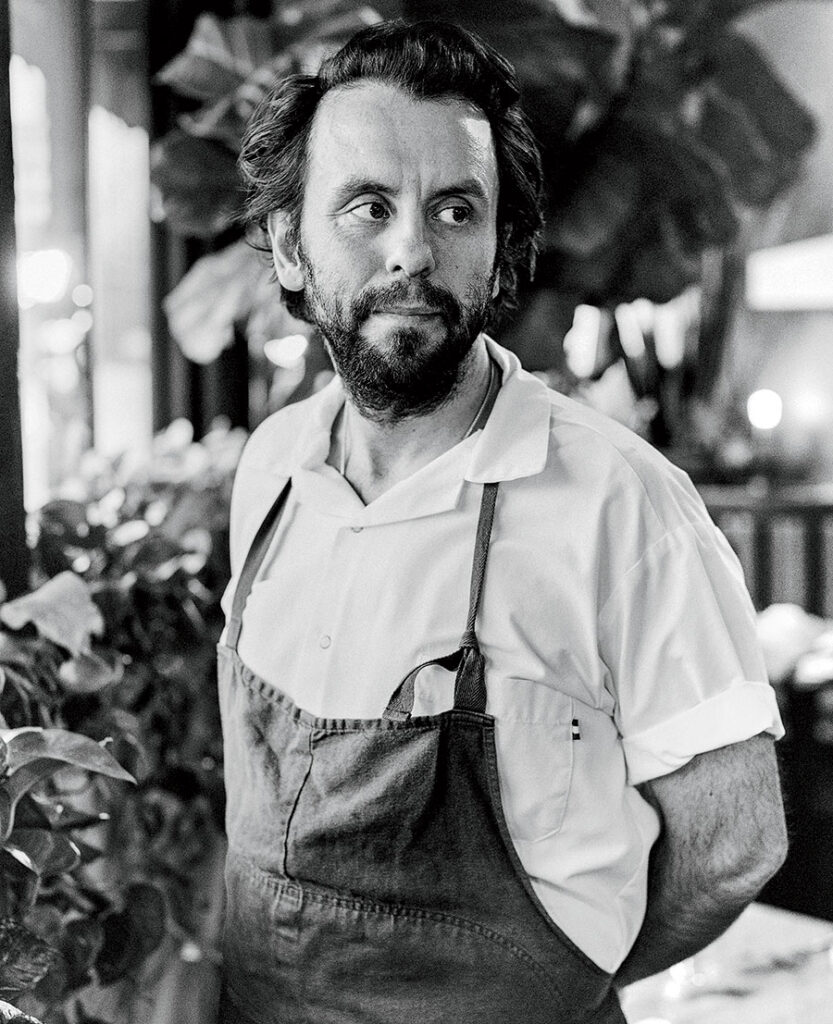

During the meal, she was up and down from her seat, talking to the many Ukrainians on staff — everyone from Milena, the young host from Donetsk, to chef Clark, who named the restaurant for his grandmother, also from Kharkiv. Last year, he traveled to that city, just 20 miles from the Russian border, and got to know a chef for whom Elizabeth had done some branding work. After dinner, my wife and I retreated to the bar to give them time to share photos and say goodbye with a hug.

Hugs are not uncommon at Anelya. Since opening in October, it has become a meeting place for Ukrainians and Ukrainian Americans. Clark and Kim sought out Ukrainian workers, taking the time to train those with no restaurant experience. The flowing emotion here, more than shared trauma, is about heritage asserting itself in a time of duress. When a culture is under attack, artists turn to its vernacular roots to find creative expression, and that is what Clark and Kim have done here.

In terms of culinary ambition, design, service, and sheer will, Anelya is a captivating aesthetic object and, I’d venture, one of the most significant restaurants to open here or anywhere this past year. It’s also an exciting place to eat, with a menu of more than 30 items, from fresh pastas and cured meats to house ferments and fancy cakes. Over two visits, I sometimes wanted the food to be a little homier, a little less expensive, a little more stop-you-in-your-tracks delicious. Yet I loved it all the same for its brash, creative energy.

What’s even more astonishing is how Clark and Kim launched it on the fly. Last May, they shuttered their previous restaurant at this site, Wherewithall, after a collapsed city sewer line left it without plumbing. Clark, whose interest in the Ukrainian part of his heritage had been awakened by the war, had recently returned from a research trip armed with cookbooks. Working with their designer, Charlie Vinz, they gave the room the sparse, industrial look Clark saw in Kyiv’s trendier dining spaces. China plates decorate the walls, and multicolored lights cast a moody glow and render the food blessedly un-Instagrammable.

Ukrainians, like Russians, often begin meals with zakusky — cured fish, salads, charcuterie, pickles, and other cold bites spread out on the table and ready to wash down with vodka. Clark and team have reimagined this tradition into a groovy cocktail hour. The Eastern European drinks are like nothing anywhere else. Try a honey-sweetened, horseradish-infused vodka, or the Lights Are Blazing, a cocktail with Bosnian rosemary brandy, sherry, and smoked pear. Order a deliciously alive Georgian Tilisma orange wine aged in the traditional earthenware amphora, or keep Dry January going with the best drink on the menu, a nonalcoholic kvass that’s made in-house from fermented rye bread and tastes kind of like birch beer. (Grandma Anelya used to make hers with leftover bread and brown sugar in an old pickle jar.)

Drinks delivered, the server rolled over a three-tiered cart with canapés. Maybe you need nothing more than a trout roe tartelette (a one-bite masterpiece) or a jar of smoked carrot pashtet (pâté) with toast. Or maybe you want a nosh-o-rama: fantastic egg mayo outfitted with anchovy and nigella seeds, house-cured herring, a puck of kholodets, a.k.a. jellied head cheese that any Southerner would recognize. Enjoy while you peruse the menu, which is filled with so many unfamiliar words your head will swim.

In fact, I wish there had been some liner notes to contextualize the menu. Some dishes are hyperregional or specific to ethnic groups, others common to both Ukraine and Russia, and still others from the chefs’ imaginations. Elizabeth and the server gamely answered my 463 questions, and we feasted. There’s much to love, starting with plump varenyky dumplings filled with potato and bathed in the silkiest saffron butter sauce. Diced smoked jowl bacon adds pops of porky goodness. Sturgeon meatballs nestle alongside buttery mash under a rich tomato sauce. I also have good news for fans of Parachute’s late, great pressed broccoli salad: A version with green raisins and baharat appears here. It’s a gem.

Others dishes intrigue but don’t push the yum button. Borscht with duck confit and smoked pear lacks brightness. (It’s also $20.) Vegan mushroom holubtsi (stuffed cabbage) doesn’t have much to say, and its clumpy coconut cream sauce further confuses matters. Desserts, such as a Kyiv cake layered with icebox-hard buttercream and meringue, seem like the earnest creations of culinary students.

The banosh turned out to be less like grits than a super-rich polenta enriched with smetana, Ukraine’s tangy sour cream, but worth a try. A woman in the kitchen named Ivanna prepares it exactly as she did back home. I respect Clark for leaving well enough alone. He is learning and tuning in to tradition as he engages this fervent cultural moment that has blossomed in response to war. The émigrés and refugees here are showing him what to do, how to move forward as the world pays attention. I feel he and Kim have created more than a restaurant at Anelya. It’s kind of a work of agitprop. Maybe even a work of art.