It began with a proverbial pebble at the peak of a proverbial mountain. And it’s why, in the darkness of a Chicago winter’s night, I am transfixed by a virtual menagerie of fantastical creatures.

A winged, three-headed beast breathes blue fire across an arctic tundra. A man-spider, with a bulbous red body, eight hairy legs, and an armor-clad human torso, hovers above an altar stacked high with human skulls and burning candles. A headless mer-creature is swallowed up by a wall, its hands clawing at the wallpaper while a silvery finned tail glistens under a pendant lamp. A landscape blooms across the page in blues and purples, castles overturned and covered by the mist of magic.

I am firmly in the world of Kim Van Deun, a Belgian artist who, after getting her master’s in biology and PhD in veterinary sciences, left academia to dedicate herself to illustration. It’s easy to surmise that her specialty is fantasy, something she confirms once we begin to email back and forth. When she was a kid, she says, her brother came home with The Dark Eye, a role-playing video game similar to Dungeons & Dragons. She found the illustrations of goblins and kobolds intoxicating: “I only wanted to know how you could draw things like that and spend your life dreaming up such monsters.”

Van Deun was able to push that childhood idea aside for years, she says, until it was “beginning to yell and throwing a ruckus in my head.” So she walked away from the promise of a steady paycheck and a pension to pursue the thing that she felt she was meant to do.

It didn’t take long for her to realize that generative artificial intelligence was going to be trouble — or that it would, at the very least, change everything — for independent artists. It was 2022, and generative AI models like ChatGPT were beginning to pique mainstream interest. The app Lensa AI had dazzled social media with the allure of summoning up instantaneous portraits of whomever you wanted, in any style you wanted. No one seemed to be thinking about how it manufactured such creations.

A couple of years earlier, Van Deun had found Fawkes, an image-cloaking software that protects personal privacy against unregulated facial recognition technology. Van Deun, who says she is “very shy,” was looking for ways to shelter the photos of herself that she uploaded to her website. It got her wondering if Fawkes might be able to do for her art what it did for a photograph of her face: give it some level of protection. She decided to cold-email its creators at the University of Chicago’s Security, Algorithms, Networking and Data Lab and ask.

And with that, the proverbial pebble — tottering and tenacious — tipped over the mountaintop and started to pick up speed.

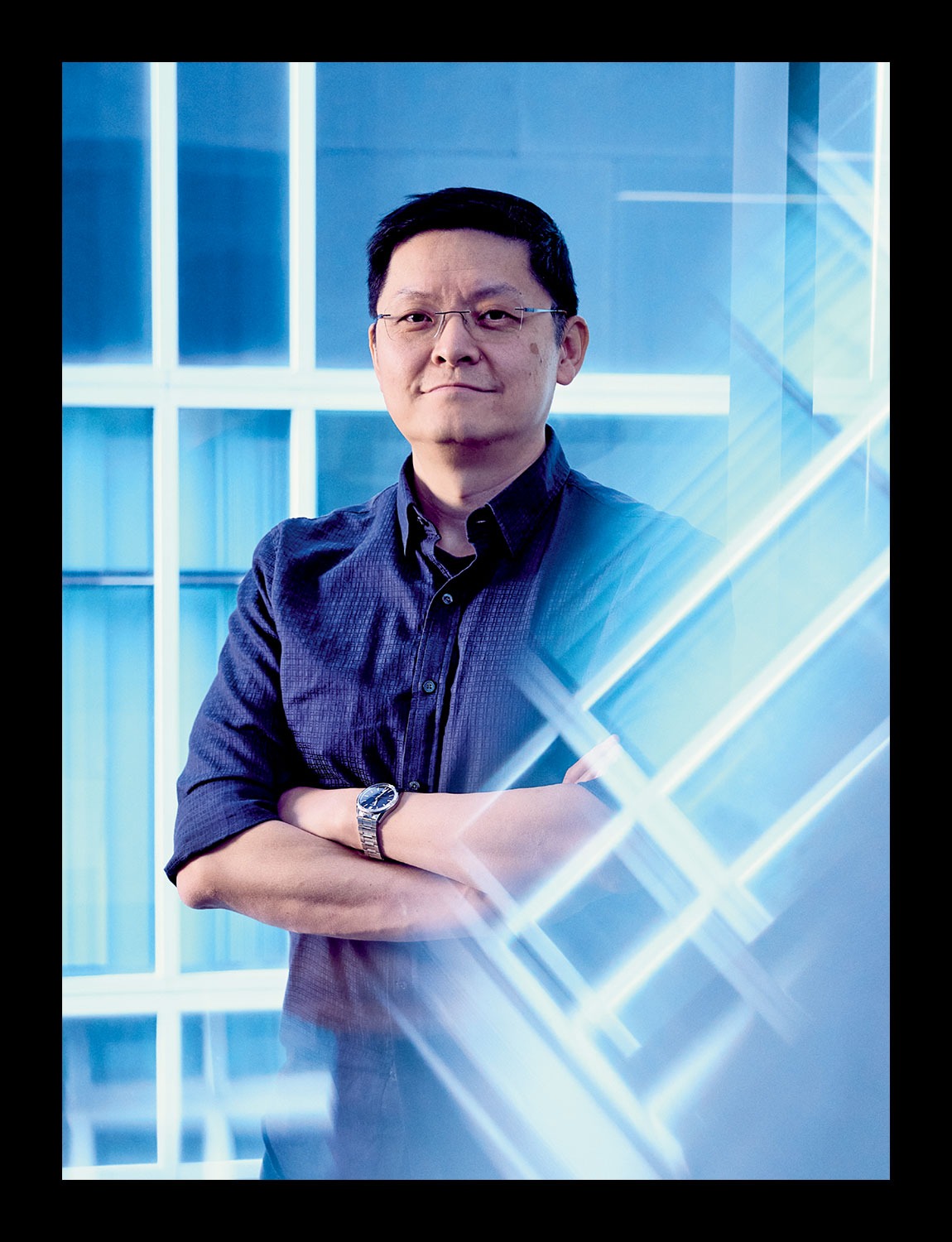

It’s 9:30 a.m. on a Monday in October, and with the exception of Professor Ben Zhao, SAND Lab is empty. Housed in the John Crerar Library, a decidedly modern building among the neo-Gothic ones typical on the U. of C. campus, the lab is austere, almost monastic, with rows of white desks that will soon be occupied by students — no more than a dozen PhDs, and perhaps a handful of undergraduates and high school researchers — working on laptops. Large windows fill the room with sunlight. It’s what you’d expect from any academic space, save for the plentiful art on the walls.

On one of the desks sits a small but hefty trophy. “You’re the first to see it,” Zhao, 49, tells me with a smile. He’s just come back from Pasadena, California, where he accepted the Concept Art Association’s Community Impact Award on behalf of the lab for its work in developing two tools that have made it famous among artists and their advocates: Glaze and Nightshade, software programs that give artists a fighting chance against a growing adversary.

I can tell Zhao is proud. It’s been two years since the CAA hosted a town hall in response to its members’ growing concerns over the impact of generative AI — which means it’s been two years since Zhao raised his hand and offered up the lab’s expertise.

Back in 2022, when Van Deun emailed the lab and found out that Fawkes, in fact, could not work for her art the way she’d hoped, she told the team there about the upcoming meeting. Maybe they could join? As a former academic herself, Van Deun was working off a hunch that if she dangled a problem in front of a group of researchers, they’d be curious enough to stick around and learn more.

Zhao happened to be free that day, so he joined the virtual town hall, hosted by artist Karla Ortiz. A recording of it is still on YouTube and serves as a reminder of both the nascent state of generative AI, already slippery and rapidly evolving, and a crucial moment of reckoning. Watching the video, I get the sense that Ortiz and the other artists were simply trying to disseminate as much information as possible to their peers, in hope of determining some kind of path forward.

At one point, Ortiz showed a chart of the main players in generative AI, all of which use large data sets to train their models. Stability AI, the chart noted, relied on an open-source set named LAION-5B. At the time, LAION-5B had already scraped over 5.8 billion images from the internet. (LAION has said it is simply indexing links, not storing the images.) And because Stability AI had used the images for commercial purposes, it was participating in what Ortiz called data laundering: employing copyrighted data and private artworks to feed the machine in an ostensibly lawful way, leaving the original owners little legal recourse.

Halfway through the meeting, Ortiz introduced Greg Rutkowski, an artist whose work has been commissioned for iconic games like Magic: The Gathering and Dungeons & Dragons. About three months before, his fans had started reaching out to him. Did he know that his name was being used as a generative AI prompt? He didn’t. But when he Googled his name, the images populating the page weren’t ones he had created, but rather copycats generated by AI. “Fake works, signed by my name,” he told those gathered.

When artist Greg Rutkowski Googled his name, the images populating the page weren’t ones he had created, but rather copycats generated by AI. “Fake works, signed by my name,” he told an artists’ town hall.

The experiences other artists at the town hall shared varied in scope, but the stark reality was the same: AI was stealing their work. It was taking away jobs. It was eroding their livelihoods.

By the time the discussion was opened for questions, Zhao was first in line. He wanted to help, he said. He brought up the lab, the work it had done with Fawkes, and suggested a few ideas, including a tool that would turn art into digital junk when it was scraped into a data set.

“Perhaps you guys would like a more cooperative role with the model — for example, you could track how much of your art was trained into the model and therefore you know how much profit could be headed back to you,” he offered. Ortiz smiled. A few months later, in January 2023, she would file a class-action lawsuit (still pending) with two other artists against Midjourney, Stability AI, DeviantArt, and Runway AI.

But first, Ortiz suggested another idea. One that was a little more proactive. Fun, even. “I would love a tool that if someone wrote my name and made it into a prompt, bananas would come out.”

It wasn’t all bad. At least not at first. Before 2022, in Zhao’s view, AI was mostly a good thing. The professor seems like the kind of person who believes in good things. But when the good things sour, he’s not the kind of person who sits idly by. His X feed is filled with posts and reposts about generative AI that attempt to expose and debunk the mainstream hype surrounding the technology. Or at least it was. In November, Zhao departed the platform formerly known as Twitter (“Left this dumpster fire,” his inactive profile reads). This is also to say that Zhao doesn’t spend time in the murky middle. He picks sides.

Zhao is a professor of computer science at the U. of C., a post he’s held since 2017. He came to Chicago by way of the University of California, Santa Barbara, along with his wife, Professor Heather Zheng, with whom he leads SAND Lab.

But before all that, Zhao was an undergraduate student at Yale who liked to wake up early and walk across campus in the quiet morning hours to the university’s art museum. Usually it would be only him and the security guards, and he’d soak in the majesty of the masterpieces. Years later, in 2017, when he announced that he and Zheng were relocating from Santa Barbara to Chicago, he wrote in a post on the knowledge-sharing platform Quora that among the reasons they were making the move was the access to art and culture here: “For me personally, I can practically LIVE in the Art Institute with [our two daughters]. Heather could bring us food to keep us alive.” A computer scientist first and foremost, but a computer scientist who genuinely loves art.

This was back when one could safely assume that art was being made by humans, and when AI was not just mostly good but ethical, even. When AI largely meant machine learning and deep neural network models (the kind of technology that trained self-driving cars).

But once generative AI went mainstream in 2022, the balance shifted. Suddenly it was possible, with a few keyboard strokes, to create pictures of anything, in any style, including crisp, detailed, photo-like images. That the technology seemed to be getting smarter by the minute only added to the hype — and the money followed. Billions of dollars have been poured into technology that’s steamrolling independent visual artists, voice actors, photographers, writers, and others.

All this masks a simple truth: Generative AI isn’t actually all that smart. “It’s truly the most useless of AI things,” Zhao tells me, leaning back in his chair. “It just really is.” There’s a frustrated resignation in his voice. The kind of resignation that comes when you’ve screamed yourself hoarse and no one’s listening.

It’s important, then, to understand how we got here. Generative AI first took off with the advent of large language models, or LLMs, which allow a user to type a prompt or question into a chatbot and receive a written response. Ask ChatGPT for an itinerary for your trip to Italy, and it will generate a schedule based exclusively on probability. Zhao is quick to remind me — in a way that makes me think he’s had to remind a lot of people — that apps like ChatGPT are far from sentient. When you feed one all the answers to all the questions that exist on the internet, it’s easy to get compelling, if not particularly groundbreaking, answers. Even where to get the perfect cappuccino in Rome. But, Zhao points out, “it literally does not know anything.”

To understand how generative AI evolved to produce images from text prompts, you have to go back to 2017, when machine learning was the main focus of AI research, which manifested as image classification: This is a statue. This is a cat. That kind of thing. Then, after LLMs were popularized, something called text-to-image diffusion models entered the mainstream.

Zhao makes his hands into fists and holds them in front of him. “Imagine two balls connected by a skinny connector,” he begins. “One ball represents everything we understand about how words relate to each other. The other ball represents visual features like color, shape, and texture.”

These diffusion models learn how to put the pieces together, using large data sets filled with images scraped from the internet. So when you ask a program like Midjourney to give you a picture of a cat, it has been trained to make sense of an anticipated pattern: whiskers, ears, fur. Maybe even a collar with a bell. Like LLMs, these diffusion models aren’t particularly smart — they’re just really good at understanding how data is arranged. And that’s because they’ve been trained on billions of images from all corners of the web.

This is what generative AI is: an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the rules that inform data and patterns. It’s also the aggregate of decades of research, which means it’s not just one thing, but a series of things that, combined, create a technology that’s perceived as magic. That there are so many components is also what makes it easy to mess with.

Take the self-driving car, for example. A lot goes into making sure the car drives accurately, that it stays on the road and doesn’t hit people. There’s complex technology (like deep neural networks), but there’s also the more straightforward tech, such as the camera that relays critical information to the car’s computer. If you mess with the camera by, say, covering up a stop sign at an intersection, it doesn’t matter how sophisticated the computer is. If it’s getting bad information, things will go wrong.

Glaze is one of two programs SAND Lab created to hinder AI models from using artists’ work without permission or compensation. The Glaze software prevents style mimicry. Take the example below, in which Glaze is applied to Claude Monet’s Stormy Sea at Étretat before it’s uploaded to the internet. To the human eye, the painting still looks like the original (left), in the French artist’s impressionist style, but AI models perceive an entirely different style — cubism (right).

After a string of unanswered emails, I’m finally on the phone with Shawn Shan, a PhD student at the U. of C. I’ve called him to talk about the work he’s doing on generative AI (or “exploitive generative AI,” as he gently corrects me) at SAND Lab, and I quickly realize that Shan wasn’t ignoring my interview requests. He just gets a lot of them. Both Shan and Zhao have been exceptionally busy this past year, presenting at conferences and giving talks. Zhao recorded a TED Talk in San Francisco in October. Around the same time, Shan was in Germany, delivering a keynote address about their work at the media conference Medientage München. Shortly before that, he was named MIT Technology Review’s Innovator of the Year for his work on Glaze and Nightshade.

Shan, 27, has been with SAND Lab since he was an undergraduate. In 2017, after hearing Zhao give a lecture about drones, 3D, and AI, Shan sent him an email asking if they could work together. Usually it’s difficult for an undergraduate to get a research position in a lab like Zhao’s, but Zhao was new to the university and hadn’t built up his bench yet. Shan was in the right place at the right time, and he was immediately hooked: “I all but stopped going to classes and just stayed in the lab doing research.”

At the time, Zhao and Shan’s research was focused on security and AI. Soon enough, they were developing the image-cloaking technology that would eventually become Fawkes. In June 2022, after Van Deun emailed the lab, it was Shan who put the CAA town hall on Zhao’s calendar. And after the two decided to jump into the fight against generative AI, it was Shan who coded the algorithm behind their first software program meant to fool it.

Zhao and Shan had studied the technology that went into generative AI images and realized that if they could mess with the model training process, they could break the whole system. Put another way: AI machines and the human eye see things differently, so pixel-level changes to images, while largely imperceptible to humans, could drastically alter what the generative AI models interpret and classify. That became the basis for Glaze, the first such tool that SAND Lab released (it can be downloaded free from the lab’s website). This was in March 2023, just four months after the town hall.

Artists can run Glaze on their images before uploading them to the internet. The software makes changes to each pixel, shifting what the generative AI models perceive. For example, an image that has been Glazed could be seen by human eyes as impressionism but as cubism by the generative AI models. If someone then attempts to use an artist’s name as a prompt, Glaze ensures the output looks completely different from the artist’s style.

If generative AI models were going to continue to train on images without consent, Nightshade would make sure those images would teach the machines unexpected and unpredictable behavior. If Glaze was built to be a defensive tool, Nightshade was designed to go on the attack.

When Zhao announced Glaze’s arrival, the response from artists was immediate and enthusiastic. Ortiz, who had given the team her entire catalog to test out the software, soon tweeted an image of one of her paintings, the first ever to have been Glazed. Fittingly, she called it Musa Victoriosa (Victorious Muse), and today it hangs at SAND Lab. Since then, Glaze has been downloaded more than 5 million times.

The success felt good. But it was soon evident that protecting artists at an individual level wouldn’t solve the greater problem of the nonconsensual scraping of images. While SAND Lab researchers had figured out how to confuse generative AI machines, they came to realize there was an opportunity to aim even higher by damaging the data sets used to train the models.

Nightshade, released in early 2024, took a more collective approach. If generative AI models were going to continue to train on images without consent, Nightshade would make sure those images would teach the machines unexpected and unpredictable behavior. If Glaze was built to be a defensive bulwark, Nightshade was designed to go on the attack.

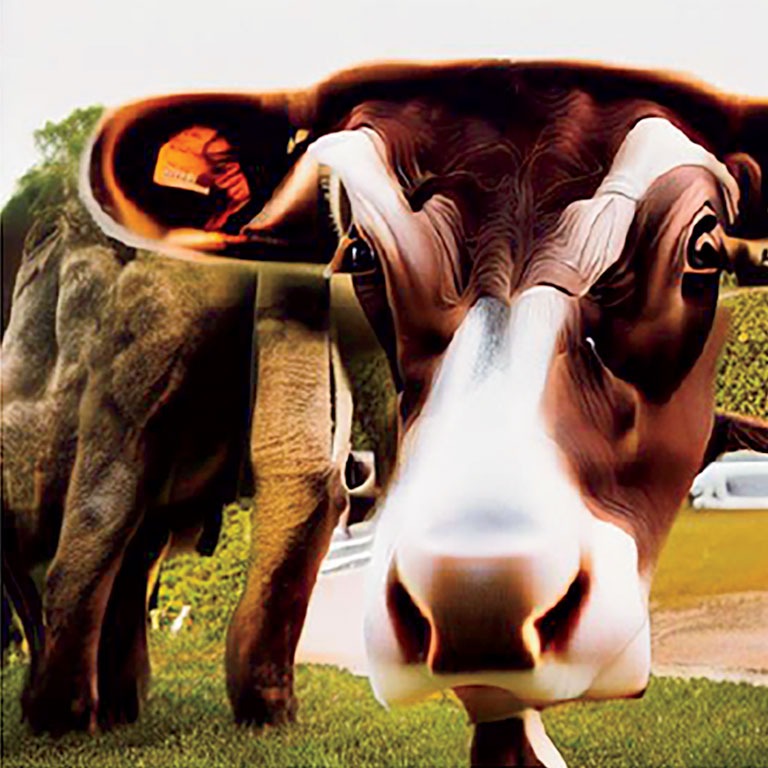

Take an image of a cat. Apply Nightshade to the image, and the AI model will see not a cat but something entirely different — perhaps a chair. Do this to enough images of cats, and gradually the model stops seeing cats and sees only chairs. Ask the same model to generate a picture of a cat, and you get an overstuffed high-back chair instead, maybe even with scrolled wooden feet. While Glaze provides immediate protection on individual images, Nightshade, which has been downloaded more than 2 million times, plays the long game. It poisons the well one image at a time.