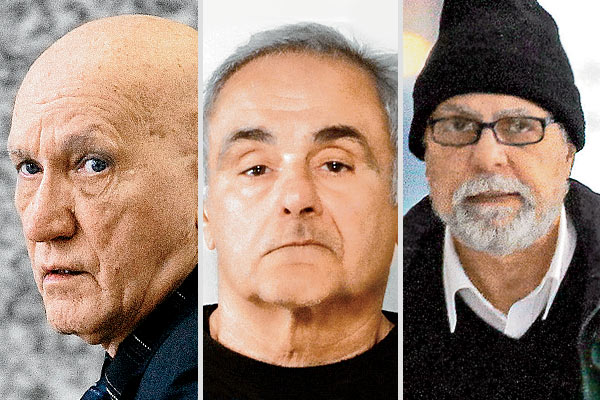

Art Rachel (left); Bobby Pullia (middle) in a 2011 FBI photo; and Jerry Scalise (right) at Chicago’s Dirksen U.S. Courthouse in January.

Related:

In an enclave of mostly multifamily dwellings in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood, the brown-and-gray brick house stands out like a palace. Flanking the front door are opulent bow windows etched with a diamond pattern. Wood shingles cover the entrance to the driveway leading to a detached four-car garage. And it is all enclosed by a six-foot-high brick wall. To convicted drug dealer and robber Robert “Bobby” Pullia, it was a “fucking fortress.” During the spring of 2010, he had spent two weeks checking it out with a couple of other ex-cons, Arthur Rachel and Joseph “Jerry” Scalise. “It’s a fortress,” Scalise agreed, “but it’s still got windows.”

Although born with a deformed left hand—no more than a knob with a pinkie and thumb—Scalise managed to scale the wall. He discovered a door to the house that was hidden from the street. To see inside before he picked the lock, he would need to remove some glass bricks from an adjacent wall.

On two successive nights, as either Pullia or Rachel stood lookout, Scalise returned with a drill to slowly and quietly cut through the mortar around the bricks. His plan, once they got into the house, was to search behind family portraits for compartments with hidden valuables.

But before the treasure hunt could begin, the three burglars would have to do something about the home’s occupant, a 68-year-old woman. If they waited for her to go to sleep, she might wake up while they were working and call police. They had to “get her before she goes to bed,” Scalise told Rachel. On the night of April 7, the two tested a can of Mace in a supermarket parking lot.

The next evening, the three returned to the house in a white Ford Econoline van and parked nearby. This time they were dressed in black from head to toe, and they brought the Mace, a six-foot ladder, handcuffs, and various tools. While Rachel remained in the van to monitor a police scanner, Scalise and Pullia stepped out for one last round of reconnaissance before the assault.

At 8 p.m., as the house’s resident sat sipping tea in her kitchen, she was startled by a loud noise. Outside her window, FBI agents in bulletproof vests and blue jackets swarmed a stunned Scalise and Pullia from all directions. The feds nabbed Rachel back at the van.

When the U.S. attorney in Chicago, Patrick Fitzgerald, announced the arrest a week later, some remarkable facts emerged. One was that the reported age of the suspects—Pullia, 69; Rachel, 71; and Scalise, 73—exceeded that of their intended victim. While most of their contemporaries had long since downshifted into retirement, this geriatric gang had already carried out one robbery and was planning others, according to a federal complaint. (The FBI had tailed them for months and had bugged Scalise’s van.)

What’s more, the place with the brick wall wasn’t just any house. It was the family home of the late Angelo “the Hook” LaPietra, one of the most powerful and fearsome bosses of Chicago’s Mafia, known as the Outfit. Though LaPietra had died in 1999, his daughter Joanne Lascola still lived there. Lascola’s daughter Angela is married to Kurt Calabrese, a son of incarcerated Outfit boss Frank Calabrese Sr. These family ties were known to Pullia, Rachel, and Scalise because the three had long been in the Outfit themselves.

To target LaPietra’s household and put his daughter at risk was not only an affront to the memory of a past don but also an insult to the Calabrese family—offenses that would have once been unthinkable. “It’s the ultimate sign of disrespect,” says Jim Wagner, a former head of Chicago organized crime investigations for the FBI. According to FBI reports and court testimony, Scalise in particular had been considered so loyal by the Outfit’s leaders that he was reserved for their most sensitive contract killings. So why did he, and the other two, do it?

Scalise and Pullia—who earlier this year pleaded guilty to charges of racketeering, conspiracy to commit robberies, and weapons violations—aren’t talking; they have not responded to requests for interviews. Nor has Rachel, who stood trial on the same charges as the other two and was acquitted on only one gun count. Sentencing is tentatively scheduled for this month. Because they have refused to cooperate with authorities, each is expected to get ten years behind bars.

Despite the gang’s silence, a close examination of the government’s surveillance tapes and other evidence—plus interviews with friends and foes and an illuminating 2008 interview with Scalise himself—helps make sense of their methods and motivations. What emerges is not just a tale of three men who refused to fade into the sunset, but also a parallel story of a Chicago Mob that may already be in eclipse.

* * *

Photography: (Rachel, Scalise) José M. Osorio/Chicago Tribune; (Pullia) FBI

Scalise (second from left) and Rachel (far right) after their 1980 jewel-theft arrest.

Related:

While most Americans associate organized crime in Chicago with the Roaring Twenties and Al Capone, it was his successors who steered the city’s Mob to national dominance. None were more powerful than the understated Tony Accardo, who reigned as the Outfit’s unchallenged leader from the mid-1940s until his death, at age 86, in 1992 (see “The Chicago Mob’s Rise and Fall”).

Early on, the key to Accardo’s success was his ability to influence local government by controlling unions and pivotal ward committees inside the Democratic Party. His clout enabled mobsters to get lucrative no-show city or county jobs, tip-offs on police investigations, even a role in picking judges. In 1951, when Senator Estes Kefauver conducted the nation’s first congressional investigation of organized crime, he called the amount of political corruption in the Second City “particularly shocking,” writing that “organized crime and political corruption [in Chicago] go hand in hand.”

While the East Coast Mafia organized its turf by families—which proved to be a source of endless feuds—the Outfit used Chicago’s freeways to slice the area into five pieces and assigned a boss for each. Angelo LaPietra got Chinatown, where the immigrant residents’ penchant for gambling made illegal casino games especially lucrative. LaPietra stood just a few inches over five feet and wore thick glasses, but with his bald head and heavy-lidded eyes, he had the menacing look of a cobra. His nickname supposedly referred to the implement he used to torture his victims, most of whom he suspected of cheating him.

Like the other bosses, LaPietra would exact a “street tax” on every illegal activity in his area, from a neighborhood poker game to a bank heist. The Outfit’s hit men, who ruthlessly enforced the tax system, killed with impunity. “The Mob had confidence that they could control investigations inside the police department,” explains Wagner. “If that didn’t work, they could pay off a judge to throw the case out on a technicality.”

Having consolidated his hold on crime in the city during the 1950s, Accardo was able to extend his influence to Las Vegas, where the Outfit used Teamster pension funds to build lavish casinos. The Mob’s slick wise guys, with their pompadours, gold chains, and silk suits, brought Vegas glamour to the bars and restaurants of Taylor Street in Chicago’s Little Italy, where they made a big impression on neighborhood teens Art Rachel and Jerry Scalise.

Though Scalise lived with his divorced mother, his father, who owned a grocery store and a car wash in Bridgeport, tried to exert a positive influence on his son’s education. He enrolled the boy at St. Ignatius, a prestigious Jesuit-run high school. Jerry did well there and won admission to Cincinnati’s Xavier University. But by 1957, at age 20, he had dropped out to pursue another of his life’s ambitions. “From the time he was a little kid,” says a childhood friend who requested anonymity, “Jerry wanted to be a thief.”

For aspiring young wise guys, the path to acceptance in the Mob often started with theft. Stealing a car or burglarizing a home proved to the bosses that a kid had the balls to break the law. And the Outfit generally took the lion’s share of the proceeds from fencing the goods.

Scalise was already an overachieving thief by 1961, when a garage where the 23-year-old was storing stolen cars caught fire. He was sentenced to probation. Before the year was out, he was convicted again of burglary and spent a few months in prison. As a cycle of increasingly serious crimes and ever-lengthening incarcerations began, so did Scalise’s rise in the Mob firmament. By the 1970s, the Outfit had made him a partner in the chop shops that sold parts to legitimate businesses.

* * *

Meanwhile, Art Rachel, one of Scalise’s oldest Taylor Street buddies, was running with mobsters too. Over six feet tall, Rachel had a gaunt, hollow-eyed look that impressed some as half crazy. Like Scalise, he had a high IQ—hence his nickname, the Brain—and also an aptitude for art, which drew him toward counterfeiting currency. In 1958 and in 1972 he was sentenced to prison time for bank robbery.

In the 1970s, Scalise’s most frequent partner in crime was gunman Gerald “Gerry” Scarpelli. The “two Jerrys,” as FBI agents called them, made an odd couple. Scalise was lanky and ferret-faced; Scarpelli, shorter but muscular and with the chiseled looks of a movie star. Together they honed a method for knocking over armored cars that featured Halloween masks and split-second timing. From 1978 to 1980, they conducted three such jobs; Rachel joined in on one of them. The heists brought in a total of $1.2 million, as Scarpelli later confessed. They must have given some of that loot to the Mob in street tax, says Wagner. They wouldn’t have been allowed to continue if they didn’t.

By this time, Scalise had ascended to the highest level of trust for a foot soldier: He was enlisted into the Wild Bunch, an elite crew of hit men who executed the bosses’ capital punishment on offenders who were either dangerous or in the public spotlight. (Other members included Scarpelli and Frank Calabrese Sr.’s younger brother Nick. Both told authorities about Scalise’s involvement.) Although Scalise did not fire any shots—perhaps because of his deformed hand—he drove the car for the men who did.

One of the Wild Bunch’s most notorious jobs, in 1980, was against William Dauber. The Mob had used Dauber as a hit man, but after his wife was arrested on drug charges, it suspected him of informing to agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration or the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. According to FBI documents, Scalise was at the wheel of a van that followed the Daubers as they left court. When they reached a lonely stretch of road, he pulled alongside the couple’s car so the gunmen sitting behind him could blast away. After the car careened off the road, Scalise backed the van up to let one of the gunmen finish off the victims.

Two months after that killing, Scalise and Rachel teamed up for the most ambitious heist of their careers: robbing a jewelry store in London’s most fashionable shopping district. The duo gained entrance dressed as Arab sheiks, with robes and fake beards. Once inside, they pulled out a gun and a hand grenade, then scooped up some $3.6 million in jewels, including the 45-carat Marlborough Diamond, worth nearly $1 million.

Scalise and Rachel managed to board their Chicago-bound flight without incident. But an alert civilian had taken down the license plate of their rented car after they fled the store, and Scotland Yard was close on their heels. While they were flying across the Atlantic, the phone rang in the Chicago office of the FBI. “I can still hear that British detective’s voice,” says Jack O’Rourke, who then ran a program to track Chicago’s most prolific robbers and burglars. “He asked, ‘Would you know a chap named Skull-lee-cee?’ I answered, ‘Do I know him? He’s practically my hobby.’ ”

Though the jewels were never recovered (Scalise arranged for a London cabby to drop them in a mailbox), the Brits had enough evidence to convict the Yanks in London’s Old Bailey courthouse. Scalise and Rachel spent the next decade in England’s toughest prisons, along with the most incorrigible bombers of the IRA. Some of the cells were so medieval, Scalise told friends, they had buckets instead of toilets.

Back home, the feds hoped that the harsh conditions would convince Scalise and Rachel to become informants in return for shorter sentences or the chance to serve their remaining years in the United States. O’Rourke even went overseas to try face-to-face persuasion.

But the still-loyal Scalise was not about to violate the Outfit’s code of silence. As he wrote to his father: “I would rather sit in jail than compromise myself.” To O’Rourke, he quoted Nietzsche: “You have your way. I have my way. As for the right way, the correct way, and the only way, it does not exist.”

* * *

Photograph: Arthur Walker/Chicago Tribune

Related:

In the 1980s, while Scalise and Rachel sat moldering in UK cells, the FBI finally turned the tide in its war against the Outfit. Operation Strawman uncovered the Chicago Mob’s secret ownership of Las Vegas casinos and an elaborate scheme to skim cash from the counting rooms. Tony Accardo escaped prosecution, but some of his top bosses, including Angelo LaPietra, were convicted in 1986 and sent to prison.

While a successful government prosecution was bad news for everyone in the Outfit, LaPietra’s fate didn’t engender much sympathy. “LaPietra was not a pleasant guy to most people,” says Wagner. “And like all bosses from that era, he had his tricks for getting back the money he paid to his crews.” For example, according to Mob lawyer Bob Cooley, LaPietra would force soldiers and Mob associates to join his Italian social club and then shake them down for contributions to his bogus charities.

Even more devastating for the Outfit than Operation Strawman was Operation Gambat (for “Gambling Attorney”). For three and a half years, Cooley wore a wire on his contacts at all levels in the Outfit, as well as on their political pawns. Over the course of eight trials from 1991 to 1997, his tapes and testimony convicted not only mobsters but also Fred Roti, then Chicago’s longest-serving alderman; Illinois state senator John D’Arco Jr.; and Thomas J. Maloney, the only judge in United States history ever convicted of fixing murder cases.

With little clout left in the courts, says Wagner, “the hit men weren’t going to put bodies in trunks anymore.” The city of Chicago, which had reported thousands of Mob killings before 1989, has had just a handful since.

During this period, FBI agents in Chicago were becoming increasingly successful in getting foot soldiers to flip. One obvious reason was that stool pigeons were now less likely to be executed by Mob hit men. But another was the growing resentment of the way the Outfit’s bosses were treating the foot soldiers. With the success of federal investigations like Strawman and Gambat, the Outfit had fewer cushy government jobs and less cash to give them, says Wagner.

One of the disaffected wise guys was “the other Jerry.” In 1988, O’Rourke confronted Scarpelli with evidence of gun violations that could have put him away for 15 years. Over the course of several hours, Scarpelli gushed forth with one of the most remarkable confessions in the history of the FBI. He named people who he said were involved in some of the Outfit’s most infamous unsolved murders and robberies, Scalise among them.

Scarpelli “was tired of the life he was living,” O’Rourke recalls, “and felt he had been screwed over by the bosses”—being denied permission to rob and being forced to take on an Outfit partner in his bookmaking operation who cheated him. Scarpelli’s understanding was that his statements would not be made public, O’Rourke says.

But in the spring of 1989, while Scarpelli was still locked up in Chicago’s Metropolitan Correctional Center, surrounded by other mobsters, a judge ruled that O’Rourke’s report on Scarpelli’s confession could be made public. Later that day Scarpelli was found dead on the floor of a prison shower room, reportedly having hanged himself with a rope of plastic bags. Any federal case based on his confession died with him.

* * *

In 1992, when Scalise and Rachel were finally released from the British prison, they returned to a Chicago Mob in full retreat. Due to the Gambat convictions, more of the old bosses were shuffling off to prison. The Outfit’s sphere of influence in the criminal world had shrunk to mainly illegal gambling. Given the much slimmer pickings, the Mob’s old foot soldiers were mostly left to fend for themselves. But the Outfit was no longer taxing them on everything they stole.

O’Rourke, who continued to keep tabs on Scalise, was surprised to find him moving into a ritzy townhouse on the Near West Side that he had bought and rehabbed with his father. (Rachel settled in the townhouse next door.) “When I saw that,” O’Rourke says, “I figured that he must have squirreled away the money from that jewel theft.”

Or he simply had new plans to get income flowing. For Scalise was soon back to “his way”—this time going after the supposedly easy money in cocaine. When a cross-Atlantic drug transaction fell through, according to O’Rourke, he pursued other deals closer to home. In 1998, Scalise walked into the middle of a DEA sting and wound up pleading guilty to intent to distribute cocaine. For that crime he served six and a half years.

Related:

By the time Scalise got out of prison, in 2006, he was 69. He had been arrested 27 times, convicted six times for serious offenses, and incarcerated for more than 20 years. He settled into the sprawling ranch house of a girlfriend 14 years his junior in the western suburb of Clarendon Hills. Together, with friends, they traveled the world, skiing in Aspen and Switzerland. From all appearances, Scalise was finally retired.

The following year, the so-called Family Secrets trial rocked what remained of Chicago’s Mob. In 2007, four elderly leaders of the Outfit, including Frank Calabrese Sr., were convicted of a range of racketeering crimes, among them 18 previously unsolved homicides. The two key witnesses: Calabrese’s younger brother Nick and his oldest son, Frank Jr.

Nick testified that when he was part of the Wild Bunch with Scalise, he had participated in hits not just on Mob enemies but also on fellow foot soldiers who had lost favor with the bosses. “The violence used by the Chicago Mob leaders against their own people since the 1970s,” says Markus Funk, one of the assistant U.S. attorneys on the case, “ultimately led to the erosion of loyalty.”

For Scalise, 2008 would bring unexpected glamour. That’s when Hollywood director Michael Mann came to Chicago to shoot Public Enemies, a movie about the bank robber John Dillinger, starring Johnny Depp. Mann, who declined to comment for this story, met Scalise and gave him the unlikely title of “technical consultant.” In a documentary about making the film, Scalise explains that his role was to help Mann and the cast get inside the head of a bank robber. “What really creates Dillinger is the ten years in prison,” Scalise tells the camera. “[He’s] rehearsing [a bank robbery]. That’s all [he’s] thinking about. . . . Day after day after day. Three weeks [after he’s out], he’s working.”

By “working,” Scalise means robbing. And as FBI agents would discover, he could have been talking about himself as well. A year earlier in La Grange, a few miles from where Scalise lived, there was a meticulously planned robbery. Two men entered a Harris Bank branch, wearing Halloween masks and waving handguns. One ordered everyone to the floor; the other stood on a plastic container to hop over the teller’s counter and grab two bags containing $119,000, which had been prepared for a weekly armored car pickup.

Moments later they ducked into a stolen minivan waiting outside, which was found abandoned a few miles away. On the gearshift there was a smear of body fluid with the DNA of a previous federal prisoner: Jerry Scalise.

* * *

FBI agents asked Chicago’s federal court for permission to shadow Scalise, permission that was not granted until December 2009. They soon found that he was spending a lot of time with his old pal Art Rachel. According to a mutual friend, Rachel had become a “recluse” since returning from the UK, spending most of his days alone, painting, when not out with Scalise. The two had another frequent companion: bulldoglike Bobby Pullia, another career criminal.

Almost immediately Christopher Smith, the investigating FBI agent, noticed a pattern to their outings. As he wrote in his complaint: “Agents observed Scalise, Pullia, and Rachel meeting on numerous occasions and conducting extensive surveillances of banks.” They focused most intently on the First National Bank of La Grange, typically appearing on Thursday mornings to watch from various vantage points as the armored car arrived.

By March 2010, agents had seen enough to get permission from the court to bug Scalise’s van. Now that the trio’s peregrinations had a soundtrack, the FBI learned that a holdup was imminent. The three were only waiting for a day when the armored car brought so much money to the bank that the guard needed a dolly to wheel it inside. If something went awry, Scalise told the others, they had only to take off their masks and walk away because “they’re looking for some young guy.”

Even more disturbing, the three discussed two prospective hits: an informant they were looking to track down and someone else who had cheated Scalise in a drug deal. Scalise explained how easy it would be for one of them to pull it off: “[If] you want to flatten someone, put on a black sweatshirt with the hood up and baggy pants and blast. Then run [around] the block [to where you] have your work car. They’ll think it’s a kid because they all run.”

Related:

By the end of March they started talking about a second robbery—a home invasion—and suddenly they put preparations for it on a much faster track than the bank job. Ironically, they were inspired by the FBI’s March 23 raid of the home of imprisoned Mob boss Frank Calabrese Sr. (The feds were looking for some of the $24 million in restitution that had been ordered in the Family Secrets case.) Agents found $720,000 in cash and $500,000 worth of jewelry hidden in the wall behind a family portrait.

Upon hearing this news, Scalise wondered if Angelo LaPietra might have had a similar in-home hiding place. He told Rachel and Pullia that he considered LaPietra and Calabrese to be “the same guys,” equally distrustful and unlikely to use a bank’s safe-deposit box.

The surveillance tapes reveal that the home invasion was not just about money. Scalise called LaPietra “a miserable person,” remembering the Hook sitting imperiously in the corner of his Italian social club, eyeing all who walked in. “Every little thing made him nuts,” Scalise said; even though the soldiers had paid to join the club, “nobody wanted to go there.”

Unmoored from the Outfit, the freelance thieves were finally allowing their resentments to boil over into a measure of revenge. Of LaPietra’s daughter, Wagner says: “I have no doubt that they would have killed her if they had to.”

While Scalise and his gang did not have many fond memories of their old bosses, they also likely felt they had little to fear from the new ones. Both O’Rourke and Wagner say that the current top boss is 83-year-old John DiFronzo. (DiFronzo’s attorney, Donald Angelini Jr., declined to comment.) Known to be slick and ultracautious, DiFronzo has owned car dealerships and other legitimate businesses and has not been snagged in the feds’ biggest cases. In recent decades, he has spent just a year imprisoned (his 1993 conviction for defrauding an Indian casino was reversed on appeal).

DiFronzo has reportedly steered his remaining crew members away from rackets that involve an inordinate amount of violence, focusing mostly on gambling. Former prosecutor Funk, however, says that these days the Mob “may just outsource the dirty work of killing to street gangs.”

In any case, Wagner says, he doubts that today’s Outfit will exact retribution on the would-be LaPietra robbers. “Maybe if they had pulled it off or hurt somebody,” he says. “Otherwise, it’s just not worth the effort.”

* * *

Pullia, Rachel, and Scalise may not fear retribution from the Mob, but they do have one formidable enemy: time. They’re unlikely to emerge from prison until their early to mid-80s. At best, they’ll have a few years of freedom left to enjoy. Why did Scalise, in particular—who has already spent a chunk of his later years behind bars—squander his last shot at a peaceful retirement? Was he desperate for money?

His lifelong friend laughs. “If Jerry was desperate for anything,” he says, “he was desperate for action.”

Director Michael Mann made a similar comment to movie critic Roger Ebert during a 2009 interview. “Jerry says you think you’re a king when you walk out of [a place] where you scored,” Mann told Ebert. “And you can’t wait to do it again.”