In December 1978, the Art Institute of Chicago made a chilling discovery: Three paintings by postimpressionist master Paul Cézanne were missing. Suspicions centered on one Laud Spencer “Nick” Pace, who worked in packing and shipping. He had asked about the value of one of the pieces and been seen carrying a package outside their storage location early one morning. When police searched his place, they found Plexiglas and a handwritten story about robbing the Art Institute — Pace claimed it was fiction — but no art. He received a suspended sentence for taking the Plexiglas. As William Currie noted in his May 1979 Chicago story “The Theft,” Pace was “one of the more unusual personalities involved in the whole affair.”

Nick Pace wants someday to be known as a writer. In fact, he says he takes menial jobs such as driving cabs and slinging hash and hanging paintings so that he can concentrate on his writing. He considers himself an extraordinary victim of circumstance.

Shortly after the story was published, events took a dramatic turn. Pace approached museum officials to ransom the paintings for $250,000. When he showed up with all three (and a gun), he was promptly arrested and later sentenced to 10 years in prison. The paintings, including the beloved Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair, were back on display just in time for the Art Institute’s 100th birthday. As for Pace, the Reader reported in 2002 that he had died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound six years earlier.

Read the full story below.

The Theft

One quiet afternoon at the Art Institute, there was some ugly news.

It was about lunchtime for E. Laurence Chalmers, Jr., president of the Art Institute of Chicago. Perhaps, as usual, he would stride purposefully — with coattails flying — into the executive dining room for a light repast. He was tapping some stubborn ash from his pipe when he heard an uncharacteristic commotion in his outer office. Very soon now his trim bow tie would jump high over his Adam’s apple, riding the wave of a prodigious gulp.

Things are usually low-key outside Larry Chalmers’s office; he and his people are not used to dealing with much harried excitement. Still, it takes a lot to make Chalmers gulp. He is known for his ability to remain cool and articulate in the face of the wealthy and the powerful — especially those bearing gifts to the museum. He runs an institution that has been, for the past 100 years, a bastion of culture and sophistication in this provincial town infamous for its hog butchers, blustering politicians, and audacious criminals.

Chalmers immediately sensed a bit of that other Chicago seeping into his office, just as the salty, pungent odor of the old Chicago Stock Yards once wafted over the city’s neighborhoods.

He was about to hear words that he may never forget, words that would fill the Art Institute’s halls with those kinds of people he seldom encountered in the art world — nagging reporters and cigar-chomping cops.

The words would touch Chalmers’s life forever. But they would also touch forever the life of another man at the Art Institute — a disgruntled shipping clerk who’d taken the job as a lark, a man quite unlike Larry Chalmers. And the words would involve a Chicago TV newsman in a scheme that could have cost him his life because they would spell “scoop” to him.

Today, Larry Chalmers remembers only that around noon on December 27th, J. Patrice Marandel “looked like a ghost” when he entered his office — an alarming sight, indeed. Marandel, curator of early painting, sculpture, and classical art, is a swarthy man with copious dark hair and a shining mustache.

“I hate to be the one to tell you this,” Marandel said in his thick French accent, “But I think we have had a theft of three Cézanne paintings.”

Soon after the discovery of the thefts, art critic Alan G. Artner wrote in the Chicago Tribune that Paul Cézanne “is widely accepted as the only major artist of the 19th century who painted equally successful portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. Each of the three paintings stolen from the Art Institute is in one of these categories.”

There was Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Armchair (1893–95), which, according to Artner, is “more a logically ordered disposition of elements than a representation of Cézanne’s wife.”

There was Apples on a Tablecloth (1886–90), a still life that moved greatly toward abstraction. Such abstraction was a development that would have great influence on 20th-century art.

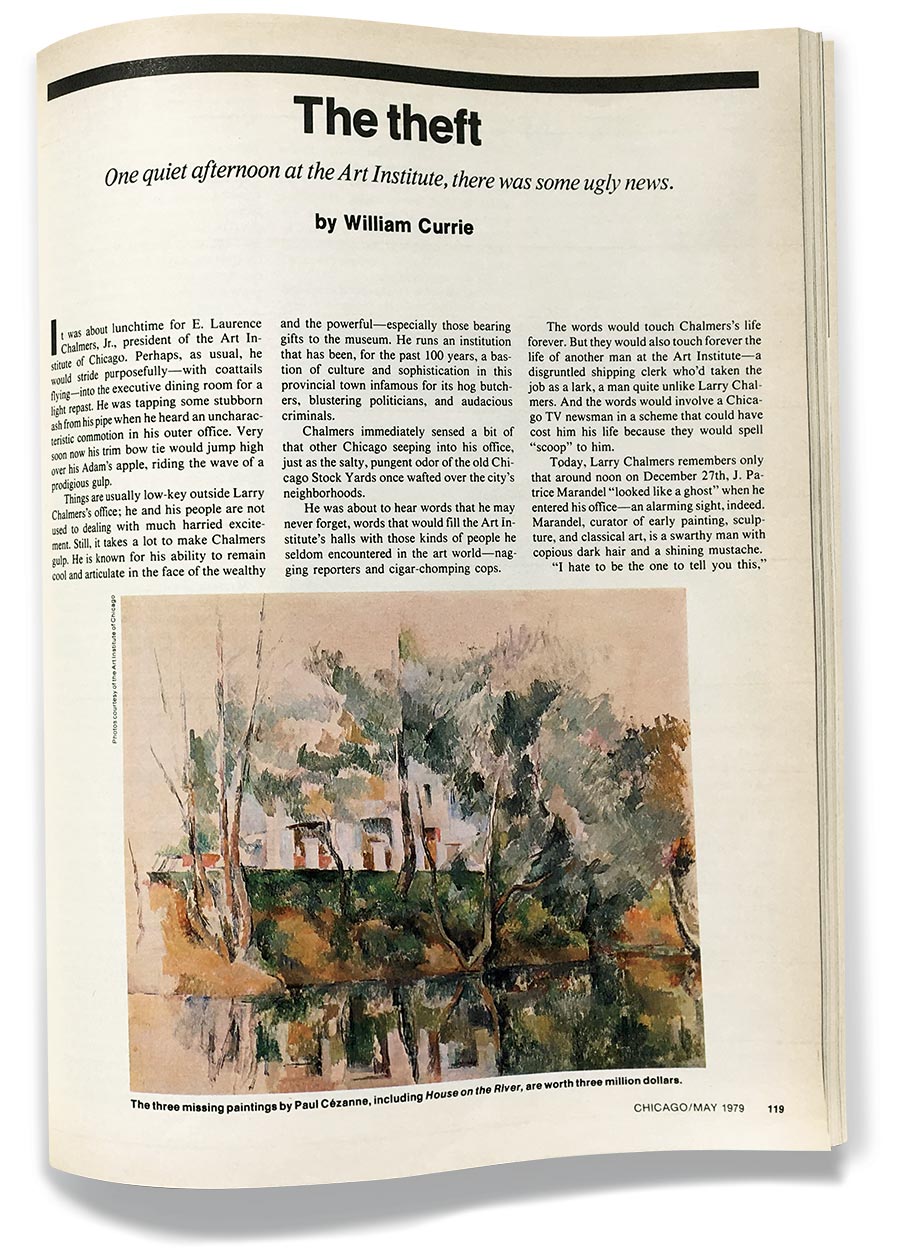

And there was House on the River (1885–90), in which as Artner wrote, “conventional perspective — a line of distance between objects — also has been eliminated from the severely flattened space… This one already opens the door leading to distinctly modern times.”

All three works represented Cézanne’s mature style. All three were treasures entrusted to the Art Institute — part of a fine arts collection that has been conservatively valued at $250 million.

The thefts stood the art world on its ear. In the next few days, Marandel would a price tag of three million dollars on the paintings. Despite later protests from Chalmers and the Institute’s hapless insurance broker, that huge amount of money can’t be shaken from the consciousness of the media.

The three-million-dollar estimate makes the Art Institute the most brutally mugged victim in a rash of art thefts all over the world. In 1978, thieves bagged $40-million worth of art — up 35 percent in a year. The Cézanne theft is the second biggest in Chicago history; only the $4.3-million Purolator vault theft in 1974 tops it. And more than half of that was recovered.

What seemed to escape the reporters and editors was that, unlike the Purolator money, the paintings can never be replaced. That thought didn’t escape Larry Chalmers. It made him shudder.

“At first we thought there was an outside chance that maybe the paintings were in the conservation department,” Chalmers said. The conservation department is where paintings are taken to be framed, repaired or otherwise worked on. The trouble was that the frames had been found in a storage area downstairs.

“[We thought] they had done a no-no, mainly to take them out of the frames in the storage area,” said Chalmers. “That was a long shot. Conservation never takes a painting out of a frame outside the laboratory.”

The long shot failed, as have all the shots that get longer and longer on a trail that is getting colder and colder. It’s been four months now since Larry Chalmers got the bad news, and everyone is still asking the same question: How could it have happened?

By late afternoon on December 27th, Chicago police and FBI agents had set up a command post in Chalmer’s office. J. Patrice Marandel was the first to be put on the hot seat.

The paintings, he told them, had been removed two months earlier with others from a second-floor gallery that was being remodeled. Rather than put them in already overcrowded vaults, he had had the paintings removed to a storage area off a nearby corridor. The paintings were last seen on November 28th, when Norman Rosenthal, a curator from the Royal Academy of Art in London, was escorted to the storage room to look at the museum’s Postimpressionists.

Perhaps Rosenthal’s response, when he was asked later about seeing the famous paintings in a narrow, cramped storage room best describes what everybody was thinking when Marandel told his story.

“Rather strange,” Rosenthal said.

The museum’s embarrassment over the room became worse when investigators got a look at it and learned that at least 300 Institute employees had access to its keys.

One investigator was quoted as describing the storage room as a mere broom closet, an inaccurate description only because broom closets tend to be high but not deep. This room was very long and very narrow but clearly not a likely place to find millions of dollars worth of art treasures stashed by a large metropolitan art museum.

Marandel went on with his story: That morning, the head of the shipping department, Reynolds Bailey, came to him with the news that one of the Cézannes was missing from its frame in the storage room. Marandel said that he then went to the storage room, where he found the two other empty frames.

Marandel also told police that Bailey had headed the six-man crew that had moved the paintings from the gallery to the storage room.

“Uh-huh,” said the police. They would want to question Bailey and his men first thing the next day.

But even before they rounded up the crew for questioning, the police were suspicious of one of them in particular — Laud Spencer “Nick” Pace, one of the more unusual personalities involved in the whole affair. Nick Pace wants someday to be known as a writer. In fact, he says he takes menial jobs such as driving cabs and slinging hash and hanging paintings so that he can concentrate on his writing. He considers him se lf an extraordinary victim of circumstance.

Late on Wednesday, the 27th, a security guard reported to the police an unusual incident that took place on the 22nd, a Friday: Pace had been seen by a custodian in a hall way near the storage room. Not so unusual, since Pace’s job took him everywhere in the vast complex. But he was seen at 6:15 a.m., more than three hours before he normally showed up at work — a time when the galleries are barely lit. And under his arm he was holding a large parcel, about the size and shape of an average painting, wrapped in brown paper.

The custodian, Antonio Vergura, told the corporal of the guard, who immediately launched an investigation. Search the walls for missing paintings, she ordered. They searched. None were missing. The incident was logged. Nobody checked the storage room, and, since nothing was missing from the walls, Pace was not questioned, though he was there at work. Later, a guard at the loading dock would remember Pace parking a car in the driveway early Friday morning.

On December 28th, the day after the paintings were discovered missing, Pace came face to face with a crew of police and FBI agents.

What were you doing in the museum at six o’clock, Nick?

“I wasn’t there,” he lied.

Do you have a car?

“No,” he lied again. At that very moment, police found two cars in front of his apartment; one was registered to him, the other to a friend.

Will you take a lie-detector test, Nick?

“No,” said Pace.

By the end of the day, Nick Pace had had it with authority at the Art Institute. He walked into the personnel office, threw his keys on a desk, and said, “I quit.”

In the meantime, he had changed the story he had given to the police. He said he had been in the storage room that morning. He had gone to the museum early to get some money from his locker — he’d been sick for two days and needed to buy some medicine. While he was there, he remembered that he had hidden in the storage room some Plexiglas that the museum had discarded. He thought that now would be a good time to take it home.

What he meant about the car, he said, was that he didn’t have one that worked. His was junked on the street, and the car that he drove to the museum that Friday morning was the one that belonged to the friend.

The police checked. The part about the car was true.

Before Pace quit, he also gave police permission to search his North Side apartment. There, they questioned the woman Pace lived with. When the left, they took with them several large pieces of Plexiglas, some plastic wrapping, and two art books, one of which contained a reproduction of one of the missing Cézannes. In Pace’s garbage, they found some of his writings.

On looseleaf notepaper, Pace had written in longhand:

“I looked at the building complex and began to work seriously for the first time. It was obvious that the escape would be the most crucial element of the operation. The target’s elaborate alarm system, complemented by armed guards, did present as much of an obstacle as did its location, Chicago’s Loop, with its abundance of police and congested streets where, even at night, a speedy retreat by car would turn absurdly unadvantageous within a matter of blocks.

“The Morton wing that jutted north from the main building at first glance gave promise. The flat-top, modern structure ran parallel to the Illinois Central railroad yards that separated the two elements comprising the Art Institute, the main building dating to the 1850s.”

That evening, the police arrested Pace for the theft of the Plexiglas, the plastic, and the two books. On February 21st, after stipulating to the facts of the case against him, Pace was given a suspended sentence. In other words, after a year, his record will be expunged, and it will be as if Nick Pace had never admitted to stealing anything.

The police questioned Pace periodically in the weeks to come. The museum offered a $ 100,000 reward for the paintings or for information about them. But they haven’t come much closer to finding Madame Cézanne, Apples on a Tablecloth, or House on a River.

The police say that they’ve been checking out new leads. But no big ones.

Well, maybe one. On January 18th, Walter Jacobson, anchorman and commentator for WBBM-TV, got a phone call from a man who identified himself as Tony. In fact, Jacobson got nine calls from Tony that day. One observer called them “drama-packed.”

Tony told Jacobson that he knew the “kid” who stole the paintings. He said the kid was scared and didn’t know what to do with the paintings. Tony said that the kid “once threatened to tear them up in 1,000 pieces and stuff them in the lion’s mouth in front of the Art Institute.”

He told Jacobson that the kid wanted $100,000–$50,000 of it for himself and $25,000 for Tony. The caller said that Jacobson could have the remaining S25,000. All he had to do was bring the money to a phone booth in the Woodfield Mall, in Schaumburg.

Jacobson jumped at the opportunity. “I didn’t want the money,” he said. “All I was thinking was that I wanted the story and I wanted to save the paintings. Not only would I be a good reporter, I’d be a hero. Right?

“I gave the guy my word that I wouldn’t participate in a trap in any way. I just care about the paintings. I think that anybody who could pull off a theft like that is kind of cool. It doesn’t hurt anybody except the insurance company.”

Jacobson then contacted Larry Chalmers, who agreed to get the money in small, unmarked bills. But before Tony could call again with final instructions, Chalmers, the police, the FBI, and a covey of lawyers were in the office of WBBM’s station manager. It seems that during the day Chalmers had learned about certain procedures that are usually followed when ransoming art things like having Tony first identify markings on the back of the paintings.

When Tony called again, he said he’d show Jacobson the markings at the phone booth. Chalmers said no deal, and everyone, including Jacobson, agreed. The deal was off, and Tony was never heard from again.

“The long and short of it,” Jacobson said later, “was that if I took the $75,000 to the mall, he would put a gun on me and say, ‘All right, give me the money’ and turn and run.” The long and short of it, according to Commander William Murphy, who is heading the investigation for the police, “was that Tony probably would have blown Walter’s head off in the CBS parking lot.”

It wasn’t until March that Nick Pace talked to a reporter about what he calls “my unfortunate burst into fame.”

The writing the police found in his garbage, he said, was an attempt at fiction. “I wanted to rob the place on paper,” he said. They were his. The plastic was from his new mattress. He hadn’t argued about it in court because his lawyer had said it might ruin his chances for a suspended sentence.

“Oh, sure I lied to the police,” said Pace, “because I didn’t know what they were looking for. But I changed my story in three minutes because at first I thought it was such a ridiculous situation. I couldn’t imagine they were after me for the Plexiglas. Here was this FBI guy acting like James Bond. And I was calling him James Bond all the time. And every time I did, he twitched like Inspector Clouseau.”

It seemed that Nick Pace just had trouble with certain kinds of authority.

“Wouldn’t you be bitter?” he said. “The whole thing is that I didn’t particularly have to quit. And I know about lie boxes. They’re not accurate. I’d get nervous and fail it. It’s just that so much pressure was put on me in such a nasty and offensive way that I decided to hell with this, I don’t need it. And I quit. But they didn’t give me the gold watch and severance.

“I gave them a hard time. That’s probably why they’re so suspicious of me. But suspicions don’t hurt anybody.

“I’ll get a job and try to write on the side. Or maybe I’ll be a Benedictine monk and walk around on my knees. Or maybe I could get a job in one of the church’s art museums.”