Among some who were there, it’s now known simply as “the worst meeting ever.” This was 2013, and Brett Batterson, the executive director of the Auditorium Theatre at the time, had just read about a survey by the advocacy group Americans for the Arts that revealed that 92 percent of arts executive directors and CEOs in this country were white. “It was unbelievable to me,” Batterson recalls. “The arts are supposed to be the place that’s inclusive and accepting and promotes differences.”

He sent an email to colleagues throughout the city alerting them to the survey and suggesting a meeting. “My thinking was, if we can address it in Chicago and create a program, then other cities can follow suit.”

One of the people who responded was Angelique Power, then the culture program director at the Joyce Foundation, which awards $30 million to $50 million in grants a year. Power, who has since become president of the Field Foundation of Illinois, has a background in the arts herself, having studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and served as the director of community engagement and communications at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. “She had some instant credibility,” Batterson says. “Whereas I was just an old white guy who was pissed off.”

Power leveraged her contacts to call about 20 directors, executives, and other leaders of local arts organizations together at the Joyce Foundation’s Loop offices for a conversation on the topic. That’s when things went bad.

Batterson was stunned by some of the comments. “We heard things like ‘This problem is going to resolve itself in 50 years because the world’s changing and there’s interracial marriage.’ I thought to myself, Really? You want to wait 50 years instead of doing what we can do now to make it better?” At that time, Power points out, discussions about diversity were different than they are now: “It was, ‘How do we keep the system — a white-dominant system — the same, but tinker at the margins?’ ”

Carlos Tortolero, the founder and president of the National Museum of Mexican Art, was also there. Listening to the abstract talk about resources and training, he grew increasingly frustrated. “Finally, I said, ‘Why aren’t we talking about racism?’ Angelique likes to say it was like a grenade fell in the room.”

The worry of being painted as racist in front of Power, who represented one of the biggest arts benefactors in town, put the attendees on the defensive. “There was fear of repercussion,” Power recalls. “People heard ‘racism’ and thought it meant they personally were harboring racist thoughts — not that the entire art and philanthropic ecosystem was designed to reify and fund white culture, and that if we weren’t actively aware of this and working against it, then we were complicit in upholding it.”

Tortolero kept pressing the issue. “You yourself, you’re not a racist,” he said to the group. “But if 10 people — 10 white men like you — make decisions for the city of Chicago, that’s racism.” As he explains now, “You can throw all these terms out, but if you don’t talk about antiracism, it’s a waste of time.”

Batterson agrees. “Angelique and I took a while to come around to what he was saying. It is lack of opportunity, it is lack of equity in funding, it is lack of equity in hiring. It is all of those things, but at the core it’s racism.”

Fast-forward eight years, and the word “racism” hardly lands like a bomb in meetings at arts organizations anymore. That’s due to changing times but also, in no small part, to Enrich Chicago, the nonprofit eventually formed out of that first meeting. These days, cultural groups around town are clamoring to sign on with Enrich, which is devoted to helping them increase diversity and inclusion in their hiring, funding, and programming. Enrich doesn’t intervene directly on specific decisions. Its approach is more conceptual and intellectual: Broaden the perspectives and change the minds of the individuals at the top of Chicago’s arts community — curators, artistic directors, executives, and philanthropists — and that will lead to more equitable practices.

Already, more than 50 arts organizations participate, including some of the city’s most prominent institutions, such as the Art Institute, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Chicago Humanities Festival, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the Joffrey Ballet, as well as smaller niche ones, such as the Puerto Rican Arts Alliance and Red Clay Dance Company. Then there’s the money end. In addition to the two groups with links to Power — Field and Joyce — Enrich works with other big arts benefactors, including the MacArthur Foundation and the Alphawood Foundation. At a time when cultural institutions risk being publicly criticized for not doing enough to create equitable environments, it may come as no surprise that Enrich has a waiting list of organizations seeking to hire it.

Getting to this point, though, has been a push. The work began right after that 2013 meeting, when Power and Batterson decided to enlist outside help for a fresh look at how to deal with the issue. They consulted Spark Design Strategies, a now-defunct Chicago-based design firm specializing in human behavior. A group of 22 top arts executives from 11 local organizations started meeting weekly to discuss systemic and institutional racism.

“If we’re saying we want to be arts institutions for the whole city, what are we willing to do differently?” Sánchez asks.

Initially, their efforts focused on areas traditionally considered solutions to a lack of diversity, like increasing the pool of qualified minority job candidates and making sure they were given full consideration. But they soon felt they needed to press further, giving diversity and inclusion training to people in charge of not just staffing but programming, administering grant money, and other facets. In mid-2014, the group decided to host a two-and-a-half-day workshop in Steppenwolf’s Merle Reskin Garage Theatre, conducted by the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, a New Orleans–based collective of antiracism educators.

Even Power, who is of mixed race (her mother is Jewish, her father Black), recalls getting her “clock cleaned.” The workshop made her look at her own situation as a person of color differently. “Many of us who are even allowed to succeed bear markers of privilege,” she says, “be it lighter skin, ‘talking white,’ demeanors that make us more palatable.”

For Batterson, the training was a shock to the system. “It opened my eyes to the ways I was failing,” he says. “How the systems of power in America that had benefited me throughout my life were in fact set up to keep certain people down, and how I had implicit bias within me of which I was not previously aware.”

Those involved in that summit wanted to create something that would be ongoing: If select leaders in arts institutions could undergo this kind of training, they could operate as “warriors” within their organizations, coaching trustees and executives and advocating change. Power, Batterson (who has since moved to Memphis), Tortolero, and the other founders of Enrich — including Joffrey CEO Greg Cameron, former Steppenwolf executive director David Schmitz, and Hyde Park Art Center executive director Kate Lorenz — imagined a “cohort model,” in which institutions wouldn’t go through this process alone but rather as part of a community with shared interests, holding each other accountable.

Enrich was formed later that year. Here how’s it works: At least three representatives of each member organization are required to complete a two-and-a-half-day group workshop called Understanding and Analyzing Systemic Racism, conducted by the nonprofit Chicago Regional Organizing for Antiracism (Chicago ROAR). In addition, Enrich visits larger organizations twice a year, and smaller ones once a year, to conduct coaching sessions exploring themes like “the manifestations of white supremacy culture in our institutional lives.” Then quarterly, the representatives from all member organizations, including at least one person of color from each, meet as a group to create goals and assess progress.

Members pay annual dues ($1,000 for those organizations with budgets over $1 million, and $250 for the rest), but much of Enrich’s funding comes from the partner foundations, which undergo the same training, and other grant givers. It received $356,000 from these sources last year. Enrich also brings in money — $60,000 last year — by providing additional consulting to member organizations and allowing nonmembers to attend workshops for a fee.

Whether you see antiracism training as educational or, as our last president did, indoctrination, whether you slant progressive (acknowledging that society must finally come to terms with the wretched ground on which it is built) or cynical (recognizing that without at least the pretense of pursuing equity, you leave yourself vulnerable to attack), the language of critical race theory has become as normalized in 2021 as corporate-speak and sports metaphors. Absorbing and repeating it carries a Rosetta stone–like quality in terms of being able to explain how the world works today. But in 2014, when it began espousing this thinking and terminology, Enrich was an outlier, at least in Chicago.

So how much does membership in Enrich reflect a genuine desire from these institutions to change, and how much is merely an appearance-driven effort to bulletproof themselves from accusations of racism? “Of course co-optation happens,” Tortolero says. “Not everybody is gonna be in Enrich Chicago because they believe in what they’re doing. That’s just being honest.”

To Power, the question is beside the point: “Even if you enter thinking that this may benefit you in one way, I guarantee it will benefit you on a spiritual and professional level. The benefits that actually come out of doing the work are there, no matter what your original intention is.”

With a staff of two full-time and three part-time employees and an operating budget of $459,000 last year, Enrich is still so small that many people in the local arts community tend to associate it with one person: Nina Sánchez, its director. She has been with Enrich for three and a half years and conducts the in-house sessions and facilitates many of the group workshops herself.

Sánchez, 42, grew up in Pilsen, right off 18th Street, and attended the same Catholic grammar school as her mother. Her father was a singer and a musician, and she describes her mom as a “crafty, creative person.” As a youth, Sánchez did community theater and sang in the church choir. She also dabbled in writing; to this day, she considers herself a lapsed poet. “Enrich Chicago has really been the moment for me to bring together all the things I love and care about and I would be doing anyway, even if no one was paying me to do it,” she says.

That includes promoting inclusion. When she was 9, Sánchez’s family moved to McKinley Park, an Irish neighborhood that was experiencing white flight amid an influx of Latinx residents. “We were the second Mexican family on our block,” she recalls. “Not only was the first Mexican family not happy to see us, nobody else was either. And so it really put us in this place of being subjected to regular, nearly daily bullying and racial slurs. Because we were fortunate to grow up in a really strong community context, it became pretty clear to me early on that there was nothing wrong with me but there was certainly something wrong with these people.”

She graduated from St. Ignatius College Prep, a prestigious Jesuit high school on the Near West Side that has come under fire in recent years because of accusations by students of color that they were discriminated against by teachers and fellow students. “I was definitely alienated,” says Sánchez, who describes the school’s approach to inclusion as “diversity icing.” She adds: “When it came to speaking up about issues of discipline, which were disproportionately wielded on students of color, when it came to speaking up in your classroom space around political ideas that were not aligned to what was being shared, when it came to standing up and advocating for the queer teachers who were being wrongfully terminated, there was very little tolerance for that kind of behavior.”

The experience had a profound effect on her — as did, in the opposite way, her earlier education. “I had a group of teachers in grammar school who were all lay ministers, who had spent time in Central America during the height of the ‘dirty wars.’ We had what I now understand to be a very liberatory education. So that politicization, paired with some very fortunate levels of access to education in private school, really propelled me. I moved away from writing and more toward direct action and advocacy.”

Sánchez double-majored in anthropology and international affairs at Colorado College, then got a master’s degree in Latin American and Caribbean studies at the University of Chicago. Before Enrich, she was at Teach for America for nearly three years; she initially worked in leadership development but soon shifted to lead the organization’s regional diversity, equity, and inclusiveness initiatives. In a way, Sánchez had spent her life preparing for her role at Enrich.

“If we’re saying we want to be arts institutions for the whole of the city, what are we willing to do differently?” Sánchez asks. “What are we willing to stop doing so that someone who looks like me can come to an institution and feel welcome? It’ll be the year 2111 before Black people have been free in this country longer than they were enslaved. You don’t undo that even in a five-year plan, but it does mean that you have to work really hard every day.”

Enrich’s philosophy — changing the values of those who administer funding, rather than simply donating money to “good causes” — runs counter to traditional philanthropic wisdom dating back to at least the 1880s, when Andrew Carnegie’s “The Gospel of Wealth” posited that the best way to close the gap between the haves and have-nots was through thoughtful, targeted giving: “All we can profitably or possibly accomplish is to bend the universal tree of humanity a little in the direction most favorable to the production of good fruit under existing circumstances.”

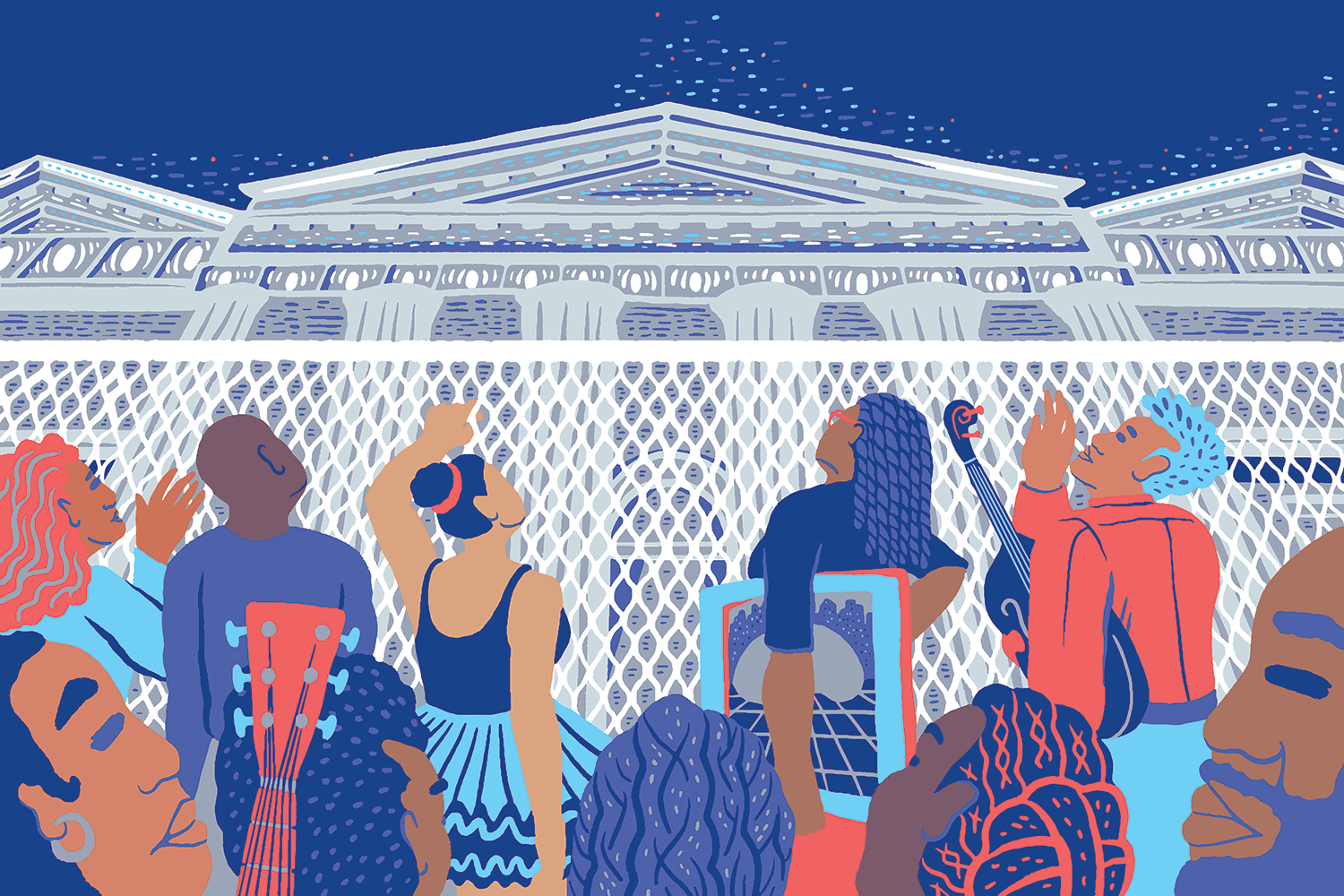

The arts have become a significant place for philanthropists to unload money, with Carnegie’s namesake classical music venue, Carnegie Hall, serving as an archetypal case. However, an unspoken rule of the art world is that dirty money can fund clean gallery installations. The Sackler family of OxyContin infamy contributed millions of dollars to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian Institution for decades. Safariland CEO Warren Kanders was allowed to sit on the board of the Whitney Museum of American Art, despite his company’s sale of tear gas that, in all likelihood, was used against protesters of racial injustice. The art world has only recently begun to question the wisdom of being financed by benefactors whose wealth may have been earned through unseemly means.

“We know philanthropy in its current form isn’t yet doing what communities of color really need and want it to do,” Sánchez says. As a first step toward envisioning an alternative model, Enrich is collaborating with the Chicago Park District on a project to identify overlooked arts organizations in town, particularly on the South and West Sides. That database will be made public, and Enrich plans to offer grants to organizations in it that demonstrate innovative approaches to antiracism.

Enrich’s trajectory overlaps with a recent evolution: how the definitions of “racism” and “white supremacy” now focus more on institutional structures than on people. That is central to the organization’s approach. The idea isn’t to tear everything down but, counterintuitively, to keep august institutions in place. The change happens in the leadership’s mindset — one executive, then one staff member, at a time. “That’s how it becomes real,” Power says. In this light, the culture war back-and-forth over what people are and aren’t allowed to say is frivolous. It’s what institutions do that’s important.

So what concrete things have Enrich’s members done? Hyde Park Art Center, a member from the start, has begun allowing families to pay what they can for its art classes in an attempt to provide more equitable access. Its staff has also formed an equity team, which is currently at work on developing transparency in organizational decision making and training employees in equitable hiring processes.

The idea isn’t to tear everything down. The change happens in the leadership’s mindset — one executive, then one staff member, at a time.

Several people affiliated with Enrich cite the MacArthur Foundation as one of its greatest points of impact. Every one of the foundation’s 181 staff members has been through Enrich’s training. And after the 2019 appointment of a white man, John Palfrey, as president sparked questions about the hiring process, Palfrey himself took the course. Under his leadership, Power points out, the foundation is “one of the most impactful organizations working on racial justice to this day.” Of its 21 “genius” grant recipients last year, 15 were people of color.

But what happens when an organization doesn’t do enough — or at least faces such accusations? The Chicago-based Poetry Foundation, which began tapping Enrich in the summer of 2018 for antiracism workshops but didn’t become a member until this January, is a cautionary tale. In June 2020, following the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the foundation put out a four-sentence statement expressing its “solidarity with the Black community” and asserting that it was “committed to engaging in this work to eradicate institutional racism.” Three days later, a who’s who of 30 Chicago poets — including Eve Ewing, Nate Marshall, Jamila Woods, and Fatimah Asghar — issued a letter of their own, calling the statement “worse than the bare minimum” and demanding the “immediate” resignations of the foundation’s president, Henry Bienen, and board chairman, Willard Bunn III. Soon after, both stepped down.

In collaboration with Enrich, the Poetry Foundation is now setting up an in-house group to craft and oversee a five-to-10-year plan that will transform the organization into what it terms an “antiracist institution.” In addition, says Sarah Whitcher, the foundation’s media and marketing director, all staffers “have attended a daylong workshop on systemic racism and dismantling white supremacy.” The board of directors also completed a workshop tailored specifically for them.

Victory Gardens Theater, one of Enrich’s founding members, is another example. Last June, it was hit with public criticism on a couple of fronts: that it hadn’t pressed hard enough to find a diverse hire for its vacant executive artistic director spot, and that during last summer’s civil unrest, it boarded up its windows instead of providing a safe space for protesters in Lincoln Park. Amid the tumult, executive director Erica Daniels, who had absorbed the open position, resigned and board president Steven Miller stepped down. Victory Gardens replaced Miller with Charles Harris II, a Black partner at Mayer Brown LLP who had been on the theater’s board for seven years. In March, Ken-Matt Martin, a Black former associate producer at Goodman Theatre, was named Victory Gardens’ artistic director. Victory Gardens had let its Enrich membership lapse in the meantime, but is now considering rejoining, according to Sánchez. (The theater declined to comment for this story.)

The Joffrey has been going well beyond its membership requirements, hiring Enrich to provide staff-wide antiracism workshops. Last November alone, more than 80 employees attended these multiday sessions, including administrative staff members, musicians, teaching artists, wardrobe personnel, and crew members. Through its work with Dance/USA and the International Association of Blacks in Dance, the company has also actively sought to get more Black dancers on the stage. And during the pandemic, it launched Joffrey for All, a series of affordable courses (as low as $13) for people interested in dance at various ages and ability levels.

The commitment Enrich demands is formidable. Of the 12 organizations that formed the nonprofit, five are no longer actively involved. In addition to Victory Gardens, Black Ensemble Theater, Court Theatre, the Old Town School of Folk Music, and Muntu Dance Theatre have stepped away for a variety of reasons. In the case of Black Ensemble Theater, founder and CEO Jackie Taylor points to time demands but says she is still supportive of Enrich’s mission. “If my staff were larger and not weighed down with multiple responsibilities, we would be active members,” she says. “We are adding our voices at other tables.” Those include the boards of Uptown United, Collective Chicago, Betty Shabazz International Charter Schools, and the National Association of Black Theater Building Owners.

Changes at the top are behind the interruption of Enrich’s relationships with the Old Town School of Folk Music, whose longtime CEO, James “Bau” Graves, retired in 2019 (though his replacement, Jim Newcomb, took antiracism training through Enrich), and with Court Theatre, whose executive director, Stephen Albert, died in 2017. Which is why Sánchez says institutions should be careful not to hinge their inclusion efforts on any one leader. “This work should never be about an individual. My goal is to make sure that antiracism work becomes a part of institutional life, that it’s reflected in their budget, that it starts to be increasingly reflected in their values and their ways of operating. If you remove that person, the people that put them there and the structure that put them there are still in place.”

The same concern Sánchez has about institutions building their efforts around an individual holds for her own organization. “Right now, I basically do everything,” she says. Between courting new members and fielding calls from existing ones, between leading discussion after discussion on the heaviest of topics and worrying about the financials, the burnout risk is real. “We’ve been trying really hard to slow it down,” she says. “Twice now in the last year, we’ve closed for an entire week and said, ‘OK, everybody, just go do something else. Rest, sleep, binge Netflix, whatever you need to do.’ ”

Power, who serves as Enrich’s cochair alongside Puerto Rican Arts Alliance executive director Carlos Hernandez, knows this is an issue. “We have to do better to support Nina and protect her. We’re working really hard to figure out how to give her better scaffolding.” The organization has already brought on six contractors as new facilitators to help run workshops, and now it’s actively looking to hire a codirector to share the workload of running the organization.

Sánchez welcomes the help. She understands it’s critical that she never let herself get too worn-down and jaded by the taxing work. “You can’t do this if you aren’t coming to it with some sense of compassion and caring for the people you’re holding these conversations and spaces with. If you can’t do that, then you owe it to yourself and your community to step back.”

How much lasting change can Enrich make? We will have to wait until current anxieties decline to know whether these institutions will sustain their commitment to making Chicago’s arts scene more equitable. But if nothing else, Enrich’s model has demonstrated how collective action can change the conversation in a community. “Anyone could’ve started Enrich Chicago,” Power says. “It survives because of so many who are willing to risk the bad meetings, the wrong words, the missteps — all for the promise of something different we will build together.”

Comments are closed.