Nothing is going to happen for at least the next 90 minutes,” Dr. Chang says.

I am skeptical of this declaration from the woman who is helping my wife bring our son into the world for two reasons. First, my knowledge of delivering a baby is equivalent to my understanding of nuclear physics. Lexi is about to get an epidural, which I assume means the baby may immediately shoot out like a cannonball. The second — and primary — reason is that a lot that wasn’t supposed to happen has happened in the past 26 hours.

Yesterday, a routine checkup for my 31-weeks-pregnant wife turned into an urgent trip to OB triage at Northwestern Medicine. She had dangerously high blood pressure and severe preeclampsia, which, if left untreated, can lead to serious complications like placental abruption, seizures, and damage to basically every organ in a woman’s body. Last night, what felt like a soccer team of medical professionals pumped her full of magnesium, reviewed her lab results, and listened to the ding-ding of a blood pressure machine every 15 minutes. The only solution to make sure that she and Walter — we already picked out his name — are OK is to deliver him 59 days ahead of schedule. To help us digest that news, a doctor from the neonatal intensive care unit tried to reassure us by sharing all kinds of data about Walter’s odds of living a healthy, normal life while informing us that we should plan for him to be in the hospital until his original due date.

“Trust me,” Dr. Chang tells me with the knowing glimmer of someone who has overseen thousands of deliveries. “You should go grab some lunch.”

I am a bystander in the miracle of life, instructed to find somewhere to do nothing while Lexi does everything. Having a child is a reminder that men have it pretty easy.

Ninety minutes gives me exactly what I need to calm my nerves: time for a beer at Timothy O’Toole’s, a basement watering hole ideal for drinking at an unrespectable hour. I order a Pipeworks Ninja vs. Unicorn and contemplate the four years of in vitro fertilization that preceded this barstool.

IVF comes with plenty of ups and downs, but the one constant is a schedule: We have structured a good portion of our lives around the third day of my wife’s menstrual cycle, the size of her follicles on days 11 to 14, the need for me to abstain from ejaculation prior to an egg retrieval (more than two days, but no more than five), the exact hour of trigger shots for ovulation, and the specific time of a frozen embryo transfer. We have been working toward being “expecting” for a long time, and now that we are in the final turn of this marathon, everything feels entirely unexpected.

I smile at the insanity of it all. No one is ever ready to be a parent, but I’m as prepared as I can be, I tell myself as I near the halfway mark of my glass. My phone buzzes. The caller ID reads “Northwestern Med.”

“David?”

It’s Maddy, our nurse. She does not sound calm.

“We need you to come back to the hospital.”

“Right now?”

“Yes, as soon as possible. The baby’s heart rate dropped, and plans have changed. So, yes, come back now.”

It has been 25 minutes. Something has happened.

I leave $20 on the bar and sprint three blocks through Streeterville and press the “8” button on the hospital elevator. I run down a hallway where two nurses usher me into an empty room and hand me a hazmat-esque gown. One of them is explaining something about how Lexi needs an emergency C-section. I put on a hairnet. Maddy opens the door to the operating room, but she receives a cautionary glare from a colleague. We turn around. Maddy asks me for my phone so she can take pictures when Walter comes out.

“He has all his fingers and toes,” she tells me when she returns to my holding room a few minutes later. “And he cried when he came out.”

I ask if Lexi is OK. The answer is elusive.

A team of NICU specialists wheel Walter into the room. I think of those blissful Instagram posts: So-and-so was born this morning at 9:23 a.m., weighing 7 pounds, 2 ounces. So-and-so and Mom are doing great. We are overjoyed with #love.

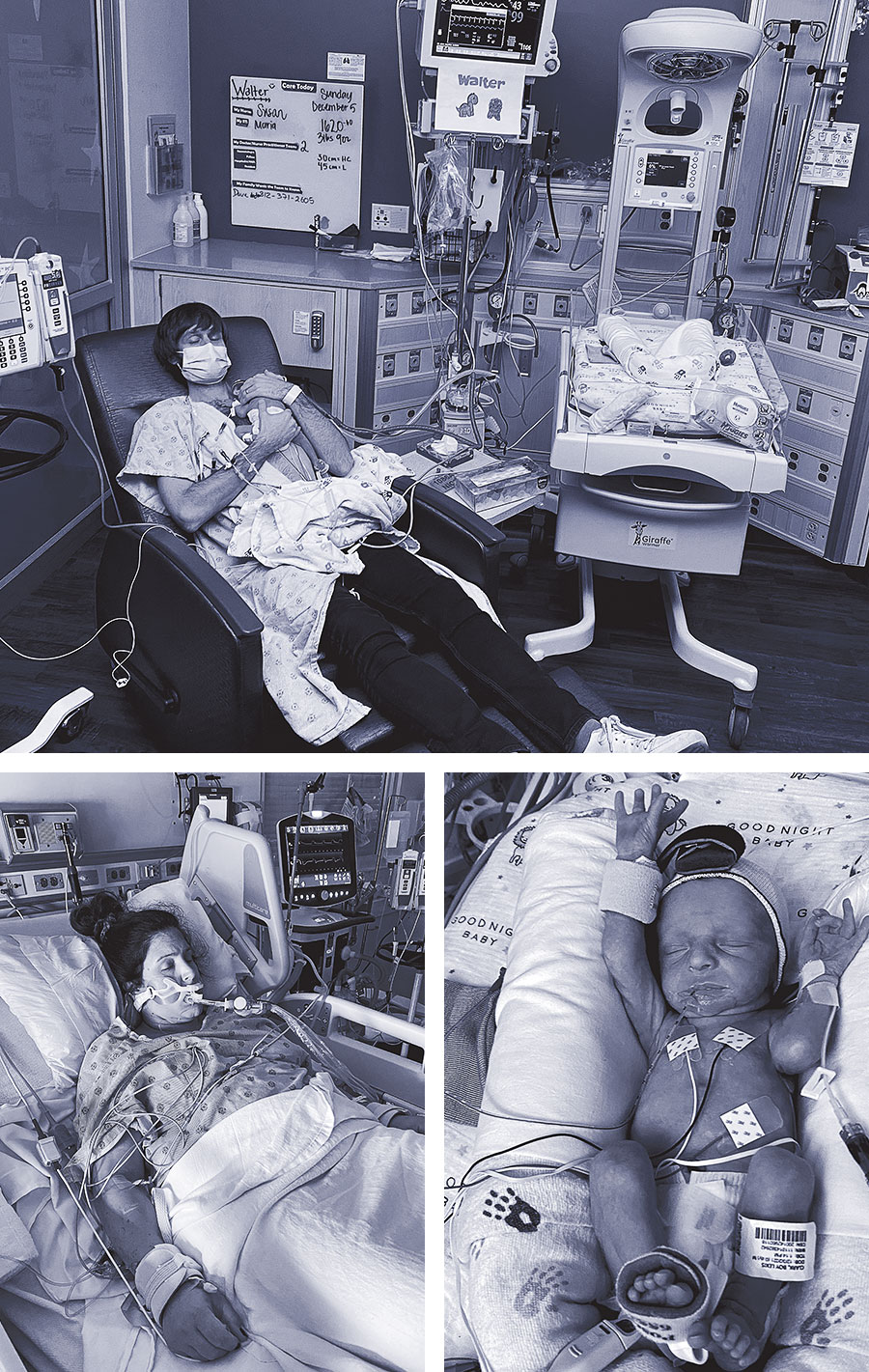

Walter is cradled in a human aquarium with 10 tubes extending from his tiny body. His mom is nowhere in sight.

Again I ask about my wife. The question goes unanswered until Dr. Chang returns, her face hidden by a mask but her eyes sorrowful. She walks me through the chain of events: Lexi’s epidural surged past its intended target, she has fluid in her lungs, Walter’s heart rate dropped precipitously, Lexi’s vitals went haywire during the C-section, and she stopped breathing.

The doctor is still talking, but my mind is stuck on the fact that Lexi stopped breathing. Dr. Chang says she will need to go the ICU to be placed on a ventilator.

My brain floats above my body. I am in the calm before the hurricane. Things move slowly. I stand up and sit down. Dr. Chang gives me a hug. Another nurse gives me a hug. Breathe, I tell myself. If Lexi could talk, she would tell me to call her parents.

Her mom answers, her flat Wisconsin accent bursting with excitement that Walter is here. Breathe, I remind myself again as I begin to say that Lexi is going to the ICU. I tell her I think Lexi will be fine, because that is what a man is supposed to say. But I am worried. My voice cracks. My lower lip is quivering. The hurricane is here.

Lexi was so excited about the nursery she designed for Walter and she may never get to see him in it and this isn’t fair and why did I leave for a beer and maybe if I had been in the room I could have known something was wrong and I can’t be a father by myself and so many people love her and she is the kindest person in the world and if she isn’t here I don’t know why I should be.

I am shaking, swallowing a mess of salt and snot. I clasp my hands, look at the ceiling, and start talking to God. It is the most committed I am to believing there is someone listening up there since I was 6 years old. You don’t understand how much you need an omniscient being until you realize that you don’t know anything.

As of 1:14 p.m. on December 3, 2021, I am a father, but I do not know how long I will be a husband. I pull out my phone and begin moving my thumbs.

I’m sitting here waiting for this army of medical professionals to wheel you by, and they have warned me that you will be on a breathing tube and that it will look scary. I am very terrified and I have been crying but since I would normally talk to you if I am scared and crying, I’m writing you this email instead.

Walter is good. Our little buddy was born at 3 pounds and 12 ounces, which feels like it would have been a lot to push through your vagina. He is an amazing little dude. I touched his foot. His feet feel big for his body. So maybe he will be a basketball player. Right now, it looks like he might have my nose. So I’m sorry about that.

I finish the email, willing myself to believe that Lexi will eventually read it and laugh. Nearly three hours after Walter’s introduction, her bed arrives outside the door. Her complexion is pale, and the person who has been smiling for every day of the 13 years I have known her is a blank mannequin. A woman in scrubs is manually breathing for her by pumping her fist on a contraption coming out of Lexi’s mouth, and the blood pressure monitor reads 220/130. I kiss Lexi on the head, and we walk through the tunnels underneath this massive complex to the ICU.

A nurse helps me understand how I will get from Lexi’s bed to Walter’s room. I visit my newborn son, and another nurse tells me she loves the name Walter. I visit my wife, and a doctor tells me they want to get images of her chest and her heart to figure out if she can breathe on her own.

It is the best and worst day of my life.

The next 48 hours hang in this balance. I sit next to Walter on the 10th floor of Prentice Women’s Hospital, where the promising potential of life fills the air. Then I hurry to the ninth floor of the Feinberg Pavilion, where the last gasp of life could be just around the corner. Watching her on a ventilator feels like I’m complicit in a war crime. Each time she wakes from a fentanyl-induced sleep, she realizes a tube is shoved down her throat, which is why her arms are restrained: to prevent her from ripping it out. She lunges forward, staring at me with a deep searching that asks, Why the hell are you letting this happen?

I watch her eyes open and close. I talk to her, a one-way conversation of attempted encouragement. I look at her phone, buzzing with friendly inquiries calling her “Mom” and wondering how the labor is going.

Slowly, the curtains pull back to reveal glimmers of hope. In the morning, she motions to me. She lifts hands that look like they weigh 10 pounds with all the cords. She wants a pen and paper.

“Is he OK?” she scribbles.

I show her pictures on my phone.

“Where am I?” she writes.

She drifts in and out of sleep, waking and heaving in a violent but silent cough.

“Thank you for taking care of me,” she writes to the nurse.

The doctors determine she can be extubated and switched to traditional, noninvasive oxygen assistance. She talks in hushed tones, her entire body ravaged by a medical assault. Turning her head requires the energy of climbing a mountain. Late in the evening on the third day of Walter’s life, the doctors say she can be moved to a standard postpartum recovery room three floors above the NICU. When I wheel her to his bedside for the first mother-son introduction, the tears of pain and terror meld into tears of joyous relief.

Approximately 700 women die every year in the United States from pregnancy- and delivery-related complications, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 50,000 women almost die. Carrying a human for nine months and pushing it out of your body or being slashed open to pull it out is not simple. There are so many possibilities for everything to go wrong.

In Lexi’s case, her epidural turned into what is known as a total spinal, a rare condition that caused anesthesia to take over her entire body. I comb through academic PowerPoint presentations to try to understand the intricacies, but I can’t make sense of any of it. The only thing I know is that, eventually, we are going to walk out of here with Walter. And when we do, it will be tempting to let this section of our lives fade away.

But I plan on keeping this page of our lives cracked open on the coffee table in my mind. When I scoff at Lexi for the boxes from an e-commerce binge for newborn clothes, I want to remember that there was a chance her name would never be printed on another shipping label. When Walter keeps us up at night crying, I want to recall the middle-of-the-night two-mile drives between our condo and the hospital parking lot when my tears flowed. When daycare pickup times and afternoon baseball games and school plays begin to feel like a burden, I want to recognize that every second is a gift.

On the fifth night in the hospital, after Lexi eats three bites of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and drifts to sleep, I walk back to Timothy O’Toole’s. I order a beer and let the hum of football fans lull me into a sense of normalcy. There is no phone call and no need to run. I walk back through a cold Chicago evening and take the long way, thinking of the people who saved our family.

Rossi, the nurse practitioner who spotted the signals of preeclampsia and sent Lexi to the hospital; Dr. Chang, who ordered the C-section; Jen, the ICU nurse who helped put Lexi’s hair into a ponytail; Vence, the nurse who gave her a sponge bath; Nicole, the respiratory specialist who cheered for her to take deep enough breaths to pass the test for ICU discharge; Brian, the security guard who wrote “DAD,” with a smiley face in place of the A, on my first pass to visit Walter; Selma, the attending ICU nurse who picked me up off the floor when I was a puddle of tears; Edyta, the nurse who coached Lexi through blood pressure readings in a thick Polish accent; the janitor, whose name I cannot remember, who cleaned our room and told us of her three-month-premature twin boys who have grown to be over six feet tall; Maddy, who wrote a birthday card for Walter while I was an empty man in that empty room. The hospital is filled with angels who work miracles in 12-hour shifts, and you hope you never have to see them again.

“Thanks for being here,” I say to the security guard who verifies my badge.

“Of course,” she says. “Everybody’s got a job to do.”

I press the elevator button and head back up to do mine.