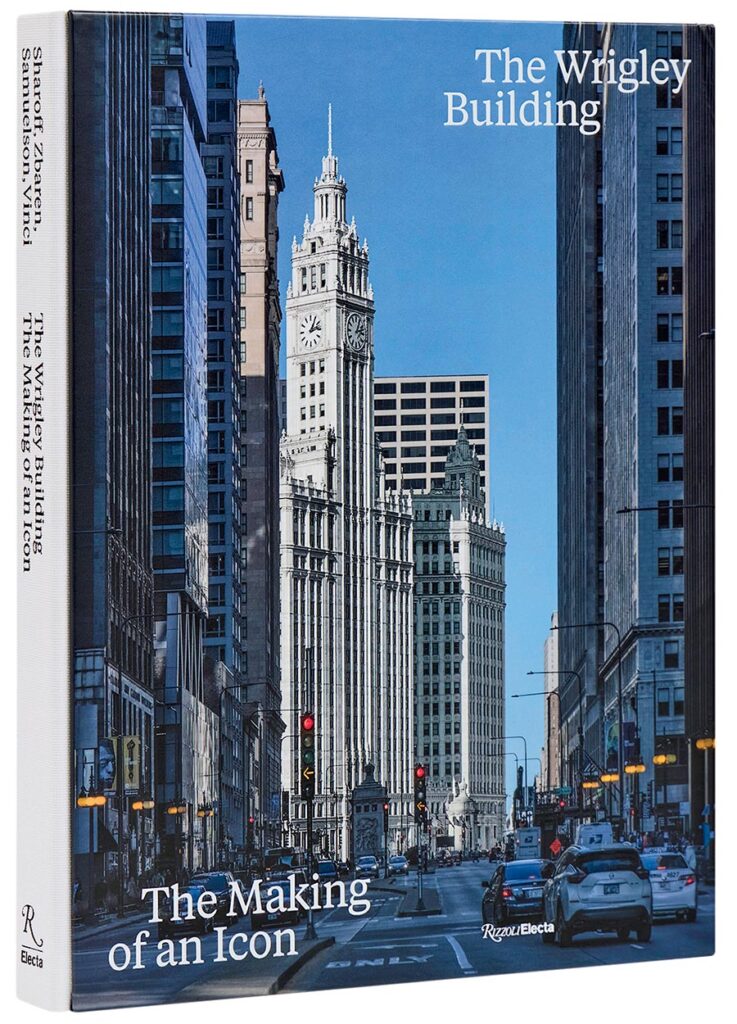

1 The Wrigley Building put the “magnificent” in the Magnificent Mile.

That moniker for North Michigan Avenue wouldn’t be coined until the 1940s, but the glitzy corridor began taking shape with the completion in 1921 of the building’s south tower, the stretch’s first major structure, a year after the Michigan Avenue Bridge opened. “As the first person to erect a new building on the north side of the river, [Wrigley Company founder William Wrigley Jr.] got the best site at the lowest cost,” Chicago architectural author Robert Sharoff writes in The Wrigley Building: The Making of an Icon.

2 People compared the new building to a castle and a ship.

Architect Charles Gerhard Beersman’s trapezoidal Beaux-Arts south tower, Chicago’s tallest building when it was completed, “functions almost as a prism, with different views from different directions,” Sharoff writes. Observing it in 1921 from a mile to the south, a journalist noted how “one can see the tower in all the airy grace of its many pinnacles and turrets much as one might glimpse the towers of some distant castle set on a rock.” But viewed from the north, it looked more like “a huge, sharp dominating prow” to another writer, who added: “It seems to cut the air and to be slowly bearing down on the spectator with an awful majesty quite overpowering.”

3 The signature clock kept poor time at first.

The building sports Chicago’s biggest and tallest timepiece, but the original gear mechanism had accuracy issues. The book quotes a ticked-off Chicagoan in 1922: “Darn that Wrigley clock. Every time I see it pointing to 20 minutes of six when I know it’s half-past nine it makes me so darned mad I just spit my wad of gum right out.” The problems included “a windswept site that sometimes made the wooden hands slap against the dial’s terra-cotta face,” local historian Tim Samuelson writes in one of his commentaries in the book. The gears were eventually replaced with a more accurate electric system.

4 The skyway was put in to save Wrigley Company workers some steps.

The north tower was added in 1924, but the 14th-floor pedestrian bridge connecting it with the original tower wasn’t constructed until 1931. Why then? “The Wrigley Company’s corporate offices on the south tower’s 14th floor had outgrown its quarters,” Samuelson writes. “Rather than expanding to other floors — thus encumbering employees with the time-consuming inconvenience of stairs and elevators — it was decided that a bridge connecting to the north tower would be built.”

5 The building was a cultural hot spot last century.

Its tenants in the 20th century were predominantly commercial and fine artists, radio stations (including WBBM and WIND), and advertising firms, such as J. Walter Thompson, which occupied all or part of seven floors in the 1960s. The Wrigley Building Restaurant “was one of the great social fishbowls of its era, a place to see and be seen,” Sharoff writes. In Studio 12 on the second floor, a who’s who of musicians made recordings for Columbia Records: Benny Goodman, Peggy Lee, Cab Calloway, Woody Herman, Gene Krupa, Big Bill Broonzy, Big Joe Williams, and Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys, who recorded “Blue Moon of Kentucky” here in 1946.