Above the rippling hills, past where a pair of Southern California valleys join to begin their golden ascent, the house . . . no, the mansion . . . no, the estate rises on a promontory like a crown.

To get there takes work. You must first pass a clipboard-wielding sentry, who fixes you with the fish eye even if your name appears on his list. Next you grind up past a bewildering succession of palm-treed cul-de-sacs, each jeweled with sumptuous homes and luxury automobiles—Porsches and Jags and Shelbys that loll in the desert sun like sleeping cats. A last climb (enlivened, occasionally, by the odd rattlesnake slithering across the road) brings you to a 40-acre property that has its own guesthouse, horse barn, corral, and baseball diamond. There you will find the nine-bedroom, 14-bath, 13,000-square-foot manor proper, with its vaulted 30-foot ceilings and an infinity pool set against a Shangri-la of flora.

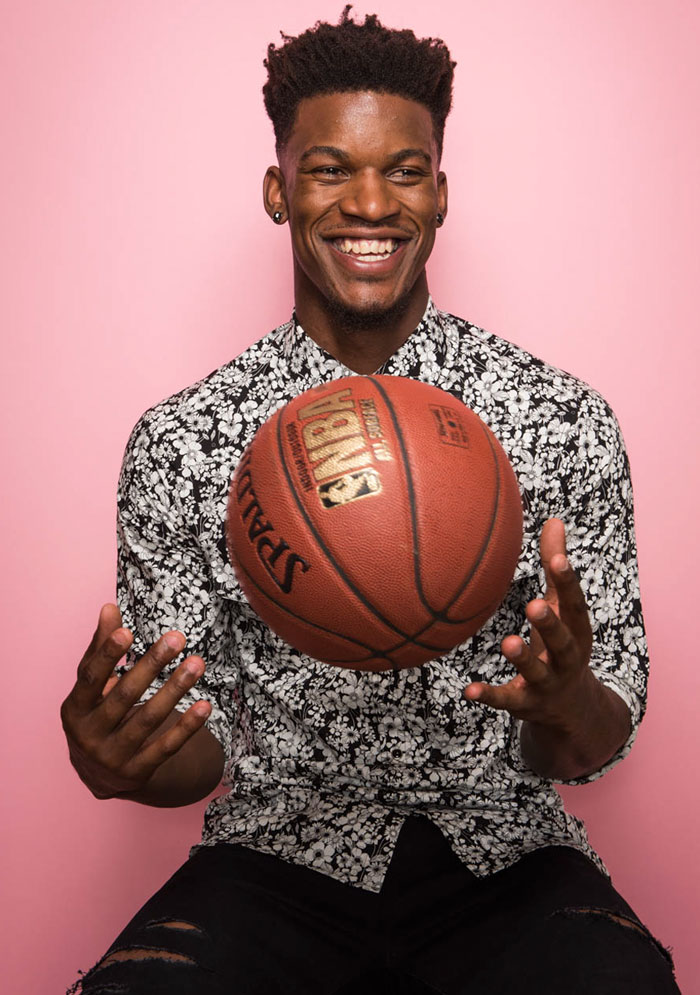

You’ll also find, in the stillness of a lazy September afternoon, a figure lying on a chaise by that pool, dozing in the Pacific breezes. His familiar Kid ’n Play meets Bart Simpson fade cuts a corrugated silhouette against the sunlight pouring down. A nugget-sized diamond winks from his left ear.

Soon enough, Jimmy Butler is up, yawning loudly and stretching. He ambles inside, dwarfed, big as he is, at 6-foot-7, by the massive house, situated in a tony enclave outside San Diego. The 26-year-old Chicago Bulls star rented it in the off-season for himself and his two longtime pals Jermaine and Ifeanyi, whom he introduces as “my brothers.”

“Nice place,” you offer, the only icebreaker that comes to mind as you follow him into the living room.

Butler laughs and nods. “Tell me about it.”

Just then, Jermaine floats past into the kitchen, a 30-foot expanse of quartz and stainless steel. Soon Ifeanyi wanders in, too, ostensibly to forage. “Don’t no one buy no groceries around here?” Butler yells over his shoulder in mock irritation.

Jermaine throws up his hands. “What? I just went.”

A five-minute zingfest ensues about who’s the most efficient supermarket navigator. (Butler: “Two hours? And that’s all you got?” Jermaine: “You hear of traffic?”)

And so it goes. The digs may be extravagant, but Butler will be damned if he and his roomies are going to tiptoe around with cups of tea and raised pinkies. “We have fun in our own way,” Butler tells me. “All the things we did as kids we do now. It’s what makes us laugh.”

For one thing, they’ve set up a makeshift indoor putting green that consists of a red plastic cup duct-taped to the carpet. And at any moment, spongy hellfire can rain down on your head. “We go to Wal-Mart and buy, like, $1,500 worth of Nerf guns,” Butler explains. “We have flat-out wars.” A too-casual walk past that Eden outside will almost certainly bring a shove into the pool—“and believe me,” says Butler, “nobody cares if you have your cell phone.”

Then, sly as a Cheshire, he grins his million-dollar grin—his $95 million grin, to be exact, given the five-year contract he signed in July, a deal that clearly signaled his arrival as the new face of the franchise . . . or at least the shared face, with the often-hobbled Derrick Rose.

What a difference a year makes. Headed into last season, his fourth with the Bulls, Butler was a $2-million-a-year, not-exactly-awe-inspiring role player good for a dozen or so points a game and solid D. Then last year—a year in which Rose, the former league MVP with the star-crossed knees, missed another 31 games—Butler stepped up to the tune of 20 points a game, nearly double his career average, while playing lockdown defense, night after night, on the other teams’ best players. He hauled in rebounds, buried game-winning shots, and ran the floor for 40 minutes a night—more than any other guy on the squad—all while playing with a passion and energy that made Bulls fans embrace “Jimmy Buckets,” as he’s come to be known because of his hot shooting streaks. By midseason, he was an All-Star. By the end of the season—a year in which he led the Bulls to the second round of the playoffs—he was voted the NBA’s Most Improved Player, the first Bull to ever win that award. There was even talk among some pundits that he should be considered for league Most Valuable Player.

“We knew we had a [talent],” says John Paxson, the Bulls’ vice president of basketball operations and, of course, a key cog in the Jordan-era championship runs. “But to ever think that he would become the player that he advanced to last year? I’m going to tell you straight out that there’s not a person in this building that saw that coming.”

Even Butler was stunned. “Hell, it came out of nowhere for me, too,” he says. “I’m not going to sit here and tell you I knew I was going to average 20 points a game in the best league in the world. I had no idea. Tell you the truth, I’d never averaged 20 points a game since high school. I was just playing ball, trying to help the team. But when I look at it now, I’m like, Wow.”

Soon he was reaping the rewards—signing that fat new contract, hanging out with the likes of Taylor Swift and Mark Wahlberg, strolling the red carpet at ESPN’s ESPY Awards (the sports world’s version of the Oscars) in a polka-dot-lapel tux and black high-tops, and luxuriating in San Diego splendor. As his publicist, Ashley Smith Becker, puts it: “It’s good to be Jimmy Butler.”

Life certainly looks fine from the mountaintop. But if you think Butler is spending all day putting into plastic cups or fighting Nerf wars, you don’t know Jimmy Buckets. Dude came to San Diego to put in work.

So if he was catching some z’s poolside, forgive him. He’d risen at 5 a.m., standard reveille for him all summer, and caravanned with his crew to nearby Poway High School for the first of three hardcore workouts that day. At 6 a.m. sharp, Chris Johnson, Butler’s basketball skills trainer, had him drilling moves—step, pivot, hard fake, shoot.

Balls ripped through the net, six in a row, then seven, eight. At a dozen, one rattled out of the rim, and Butler hissed through his teeth. “Don’t worry about that,” said Johnson, who wanted him to stay focused on the move itself. “That was good, that was good. You gettin’ it.”

When the school’s basketball coach came in at 7:30, followed by a trickle of awestruck students, Butler pleaded, “I got five more minutes, Coach. Please?” The coach grinned. “No worries.”

Later, the question will come up: Where does Butler get his work ethic? “I think it comes from not having much all your life,” he says. “And whenever you’ve got to grind for everything that you’ve ever had, whenever you do get a little something, it’s not satisfying enough for you.”

All through the workout, while Butler toiled, Ifeanyi tended to the music: Z-Ro and Slim Thug, Big Moe, Lil’ Keke—a far cry from the twangy tunes that Butler, a Texas native, grew up liking. Jermaine, meanwhile, retrieved balls and zipped them to Butler, occasionally jumping in to put a hand in his friend’s face. At one point, Ifeanyi, Jermaine, and Johnson triple-teamed Butler during a midrange shooting drill.

Saying that Butler takes care of his friends is like saying Jordan was a pretty good player. They are virtually inseparable, with Butler taking them on trips, keeping them in cars and cash, and indulging any want. Why train in San Diego? It’s not out of Butler’s secret yen for sailing, but rather as an accommodation to his buddies. “I let them choose where we would live this off-season,” he explains. “They chose San Diego. I wanted my guys to enjoy the life we will live for the rest of our lives. They work just as hard as I do.”

And there’s the rub. More accurately, he insists that they work as hard as he does—or at least try. Because for Butler, there is strength in solidarity. “I have to travel, they have to travel,” he says. “I make them train at the same hours I train. I think I work pretty hard. And if I’m working, you best bet your last dollar that these lazy bums around me are working as well. Around here, if you don’t work, you don’t eat.” (In mid-September, Butler found a new in-season pad for himself and his pals, plunking down $4.3 million for a four-story, six-bedroom house in River North.)

So seriously does Butler take the idea of sacrifice that he uses that word, in big block letters, as his phone’s screen saver. And, in a kind of basketball Lent, each off-season, he and his roommates agree to give up one major activity to allow more time for training. The summer of 2014 it was no cable and Internet. This summer: no going out to party. (Well, less going out.) “Staying home is way harder” than last year’s sacrifice, says Butler: “We are in bed on a good night by 10. On some bad nights, 12. Because 5 a.m. comes around early—and you’re up, grinding, grinding, and grinding.”

Butler’s disciplined approach to life comes as much as anything from an unlikely source: his friendship with Mark Wahlberg. The two met in the fall of 2013, when the actor was in Chicago filming the latest installment of Transformers. Wahlberg dropped by the Berto Center, the Bulls’ old training facility in Deerfield, in search of a basketball game. “He was like, ‘I want to play,’ and we were like, ‘Let’s hoop,’ ” recalls Butler, who admits to being a little starstruck. “I was like, Damn, this is the first bigtime famous individual that I’ve met.”

The next night, Butler joined Wahlberg and his entourage at Lucky Strike. Wahlberg had rented out the bowling alley to watch a boxing match on TV. The two exchanged numbers, but Butler was reluctant to reach out. “I didn’t text him because it was awkward,” Butler says. “He’s a really good dude and I wanted to thank him, but I didn’t want to bother him.”

Finally, after a few weeks, he worked up the nerve. “I was just like, ‘Hey, man, I’m checking in. Hope all is well,’ ” Butler recalls. “And he’s like, ‘Whenever you’re in L.A., come to the house, meet the family, the kids.’ ” On the Bulls’ next West Coast road trip, Butler took Wahlberg up on the offer. “Ever since then, he’s been my guy,” says Butler. He accompanied Wahlberg on a private-jet trip to Paris last year and did the same this summer—a summer in which the two hung out for nearly four solid weeks.

“I love him to death,” Butler says. “He’s always asking about me as a person. Forget Jimmy Butler as a basketball player. ‘Hey, you doing OK? Is there anything I can help you with?’ I try to pick his brain a little bit.” One thing that impressed Butler about Wahlberg, in addition to the actor’s commitment to his wife and kids, was his work ethic: “I just saw the way he got after it, the way he would train. I was like, You know what? That’s probably something a lot of people aren’t doing. Which is why I started waking up at 5 a.m. to start working out. He was doing it.”

Says Wahlberg about his bromance with Butler: “We just kind of clicked. For me, it’s exciting to see a young 20-something-year-old kid, who’s got the world basically in the palm of his hand, controlling his own destiny. Just to see the excitement in his eyes, but also a good, strong head on his shoulders. There are a lot of people who will try to come around and get on his good side to get something from him. And he knows that I don’t need anything from him, that all I’m trying to do is point him in the right direction.”

It’s not random that Butler chose staying in as his crew’s sacrifice. Explains Wahlberg: “I told him, ‘Look, I was lucky. I got it all out of my system when I was younger. When I was your age, I was not disciplined, but if I had been, I think I’d be a lot further along in what I’ve wanted to accomplish. If you don’t give it your all now, you’re going to regret it. You’ll look back on that time you wasted going out and having fun, spending all hours of the night out instead of all hours of the morning at the gym.’ He just got it.”

If Wahlberg comes off as a bit of a father figure to Butler, there’s good reason. Bulls fans who have closely followed Butler’s career are familiar by now with his early life, an ugly chapter that began in Tomball, Texas, a town of about 11,000 just north of Houston, and was first detailed in a 2011 story on ESPN’s website. Butler’s father wasn’t around for the early part of his life. Then, following a dispute, his mother kicked Butler out of the house when he was 13, with the words, “I don’t like the look of you. You gotta go.” He was taken in by a high school teammate’s family, to whom he expresses deep gratitude even now.

Still, he loathes reliving the past—so much so that he has removed the rearview mirror on his car (yes, really) as a symbolic reminder to never look back. His coach at Marquette University, Buzz Williams, says Butler was so sensitive about his upbringing that he swore Williams to secrecy while playing for him.

When I ask why he hates talking about the past so much, Butler shifts uncomfortably on the sectional in the grand San Diego house. “It’s because I don’t ever want that to define me,” he says. “I hated it whenever it came up because that’s all anybody ever wanted to talk about. Like, that hasn’t gotten me to where I am today. I’m a great basketball player because of my work. I’m a good basketball player because of the people I have around me. And if I continue to be stuck in the past, then I won’t get any better. I won’t change, I’ll get stuck as that kid. That’s not who I am. I’m so far ahead of that. I don’t hold grudges. I still talk to my family. My mom. My father. We love each other. That’s never going to change.” In fact, the day I visited Butler, his father was staying with him.

(Butler’s less-than-idyllic upbringing may explain the roots of one ritual that has become a rule with him and his roomies: When you go to the grocery store, you pay the bill of the person behind you in line. “I don’t care how many groceries they have. It could be a 99-cent ice-cream cone or a $2,000 grocery bill,” says Butler. “We have been so blessed. It’s fun.”)

In high school, Butler was the best player on his team but hardly the kind of star who attracted attention from major colleges. Tyler Junior College in Tyler, Texas, was the only school that showed real interest in him. After a year there, Butler transferred to Marquette, where Williams, who had just taken over as head coach, brought him in solely on the word of a Marquette player who had been Butler’s teammate at Tyler. “I never sent Jimmy a letter, I never sent him a piece of mail, he never took a visit to Marquette,” recalls Williams. “He faxed his national letter of intent from the nearest McDonald’s. And that’s how we signed him.”

Williams rode him hard from the get-go. One of the first things he said to Butler—and continues to say, as a running joke—was, “Jimmy, you suck.” Says Williams: “I was bordering inhumane how I coached him. But I was brutal because I wanted him to make it. He was weak, he was overwhelmed, but he never quit. Jimmy just kept showing up, kept showing up.”

By his junior year, Butler was a starter. Over the course of his last two seasons, he averaged more than 15 points a game, while earning a reputation as a strong defender. He never even made all-conference in the Big East, but in 2011 the Bulls and their defense-minded coach, Tom Thibodeau, drafted him in the first round, the 30th pick overall. “You just loved his toughness,” says Thibodeau, who lost the Bulls job at the end of last season. “When we drafted him, we didn’t know how good he was going to be, but we definitely felt like, OK, this guy is going to be able to work himself into the rotation quickly.”

Fans weren’t as happy with the pick. “A lot of people wanted offense,” says Bill Wennington, a former Bull who is now a color commentator on the team’s ESPN radio broadcasts. “Jimmy came in not being able to do that or not known for doing that.”

In Butler’s lockout-shortened rookie year, he played sparingly, averaging a measly 3 points. But each off-season, he worked on his game. And each subsequent season, he improved—to 9 points per game his second year, then 13 his third. The real turning point came when Butler began working with Chris Johnson a couple of seasons back. “I told him, ‘Give me two years and I’ll make you an All-Star,’ ” the trainer recalls. Adds Butler: “And he was right. He was right.”

But no one could have foreseen the success Butler had last year. Before that season, the final one under his rookie contract, the Bulls offered him an extension: $44 million over four years. Butler was tempted. “Forty-four million is a lot of money,” he says. “It was more money than I ever thought I’d have.” He decided to turn it down and roll the dice: play out his contract and hope to sign a bigger deal as a restricted free agent at year-end. “I was nervous, I’m not going to lie to you,” says Butler. “But everything I put myself through, I knew what I was capable of.”

The gamble, of course, paid off bigtime. After Butler signed the $95 million deal, Wahlberg threw him a party. “We had quite the dinner at my house,” says the actor. And though Paxson now has to sign the paychecks, he is equally delighted. “For years, as we’ve been trying to build the team, it’s always been, ‘You need a complement to Derrick Rose,’ ” he says. “Well, we’ve got one.”

But adding a star to a team that already has one isn’t always a smooth transition. When Rose returned to the lineup late last season, he had to adjust to the fact that Butler had become the team’s primary scorer. And his unease with that, according to a report on the website of Chicago’s CBS affiliate, culminated in some bad chemistry during the playoffs. In the second half of the Bulls’ elimination-game loss to the Cleveland Cavaliers, Rose, looking a bit lost, attempted only four shots, while Butler, perhaps forcing things, put up three times as many.

Naturally, the front office plays down any tension. “If you’re asking about their relationship, only Derrick and Jimmy can speak to that,” says Paxson. “Our concern is how they blend on the basketball court and how that translates into winning, and I don’t envision anything other than both those guys and everybody else putting their best foot forward and trying to win.”

Butler treads lightly on the matter but does acknowledge, albeit in a supremely diplomatic way, a shift in team leadership. “I think people look at me now as kind of, maybe, the face of the Chicago Bulls,” he says. “When you think of the Chicago Bulls, yeah, you think Derrick Rose, Joakim Noah, and Pau Gasol, too—but maybe every now and then you think of myself.”

What about his relationship with Rose? “I think our relationship is great,” Butler says. “I think we each want each other to be successful. And I think we share the goal of wanting a championship. I think if we just continue to change for the better, build off of each other, then we’ll be fine. We are fine.”

The first two workouts of the day done, Butler, Jermaine, and Ifeanyi mull over the idea of playing a round of miniature golf. With a wager, of course. There’s always a wager. And the stakes are never small—in this case, $1,000. But the afternoon is growing late and traffic is already building.

Instead, Jermaine has a better idea. They could go to the golf course just down the street, pay for full rounds, and simply putt the greens. And so, bearing two putters and one ball to share among them, the three young men pile into golf carts and zip past the first fairway of the nearly empty course to the green. Butler doesn’t love golf (Wahlberg theorizes that he is hesitant to embrace the game until he’s mastered it), but he does love to putt.

Over the next hour or so, he and his friends rule the course, racing down cart path slopes, mocking each other’s awful putts, woofing back and forth, laughing, sneering, gloating, and generally doing all the things that close friends (and brothers) do. In the end, Jermaine, the golfer in the crew, ekes out a one-stroke win, sending the competitive Butler into a semifunk.

Walking to the parking lot, however, Jermaine erases any vestige of irritation. The group has just passed a pipe spilling water into a drain. “Give me $7,000 and I’ll drink it,” he says to Butler.

Butler counters: “Man, you crazy. Seven thousand? That’s worth, like, $1,500, tops.”

“Man, that’s sewer water,” Jermaine protests. “You gave me $5,000 for drinking syrup!”

“Well, that was a lot of syrup,” Butler says.

“It was,” Jermaine nods. “Damn.”

“Now,” says Butler, his mind churning, “if you lick the inside of that trashcan, that’s worth $7,000.”

“Psh. You crazy. Raccoons be licking on that. They got rabies!”

The group howls, Butler louder than anyone.

In the fading afternoon, the three jump into Butler’s Mercedes G-Class SUV and begin the slow ascent to the grand house, past the guardhouse, past the other beautiful homes, headed back to the top.

Butler would love to take another nap when he gets there, but he can’t. He has one more workout to go, then dinner, then bed. Five o’clock comes early.

Comments are closed.