This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

She had the It factor. He had vision and connections. Together, the two globetrotting Southern transplants became a Chicago power couple whose family would live in a 12-room brownstone on King Drive (formerly South Park Way) in Bronzeville for nearly 50 years.

Etta Moten Barnett was a fashion-forward actress who starred in the 1942 Broadway revival of Porgy and Bess and sang in films such as Ladies They Talk About and Flying Down to Rio. She was a trendsetter and a hot topic — even later in life, when she joined federal delegations to Africa on cultural missions. There’s a photo of her wearing a full leopard-print outfit while posing with a live cheetah in front of the Paradise of Princes, a palace in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

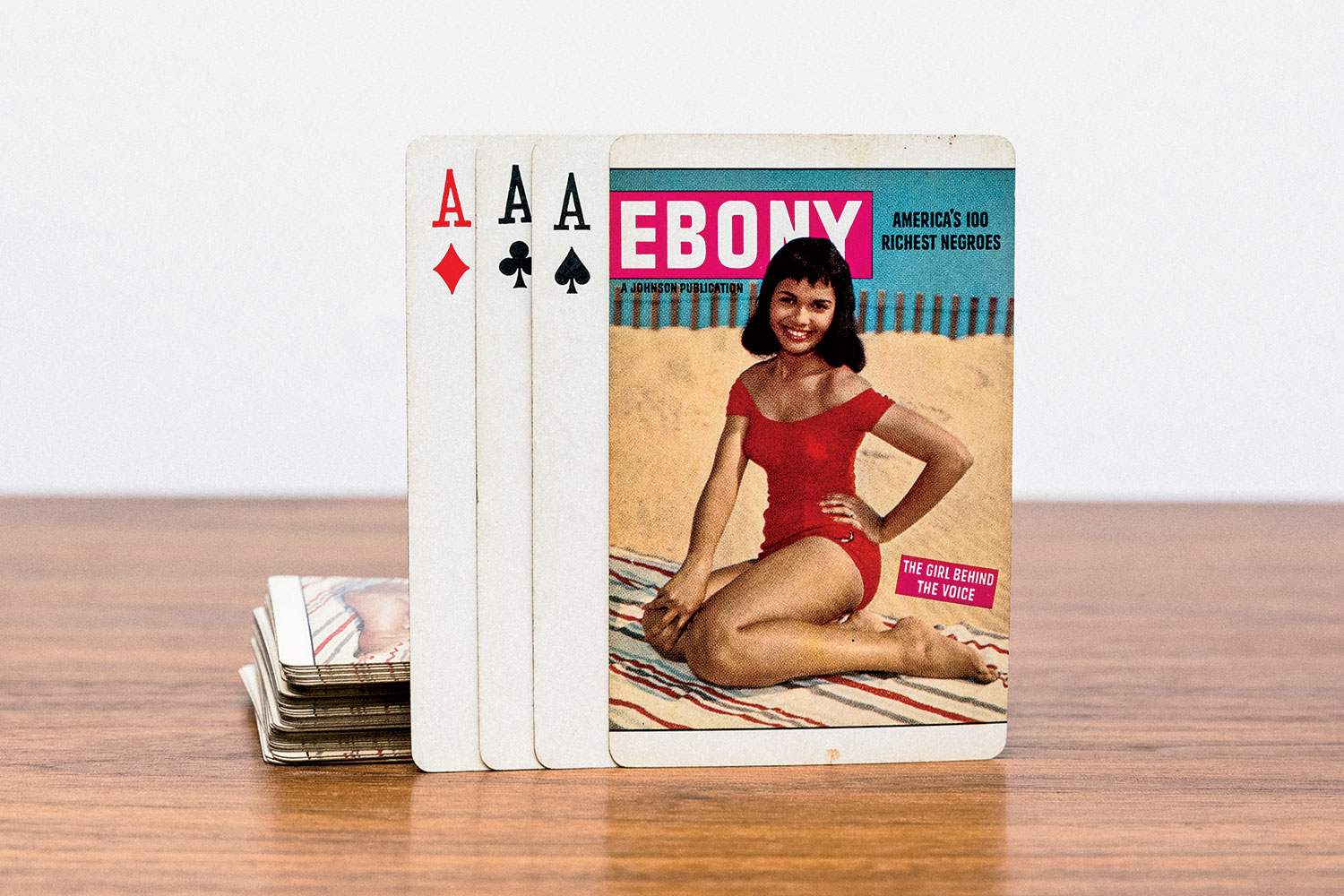

Claude A. Barnett was best known for his Associated Negro Press. Passionate about amplifying Black voices, he also served as a mentor to John H. Johnson, founder of Ebony, Jet, and Tan magazines.

The Barnetts died some time ago — Etta in 2004 at age 102, Claude in 1967 at 77 — but the story of their lives came back into focus this fall when Lynn Rousseau McDaniel staged an estate sale of their possessions. A portion of the estate also went to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, DC. To McDaniel, the Barnetts were more than money and power; they were an American love story worthy of national remembrance. We talked with McDaniel, who’s co-owner of the Logan Square furniture shop An Orange Moon, about the Barnetts and her work.

I decided to name the Barnett estate sale “An American Love Story” because as we went through their documents and saw the communications between the two of them, the main message was all about love.

It’s important for the world to know that people of color have wonderful relationships with each other. The media never really focuses on love. We have a couple of great Black love movies. For my husband, Ty, and me, our favorite is Love Jones. However, we never talk about Black love. Black people love each other, we love people, and we are open to embracing love. Black people are very romantical — that’s what I like to say. I know it’s not a word, but I love it: “romantical.”

When I first met Ty, he bought me a dozen yellow roses the size of my fist. I’m thinking, “This brother has got potential,” because he was romantical. That’s the same thing I noticed about Claude and Etta.

Claude’s office was packed with signed photos, including a big portrait that Etta signed: “My darling, I love you with all my heart.” And some of the letters that he would send her, his sweetness, were just … Oh, I want to cover my eyes.

Everybody wanted a piece of her. There’s a Sidney Poitier letter that had me asking, “What did his wife say?!” It’s a public letter on letterhead and everything.

I need only to close my eyes for a moment and I am back in the mid-nineteen forties at the Belasco Theatre rehearsing for “Lysistrata,” starring the most beautiful woman I had ever seen in my life. The most incredible, amazing, voluptuous, dignified, and sensual actress to grace the Broadway stage in my lifetime — the incomparable Etta Moten Barnett.

— Sidney Poitier, October 2, 2001

The person accompanying her told me that Etta’s response to Poitier’s attention was, “You know what? Tell that boy I can’t be bothered. Go, tell that little boy to go.” Everybody wanted her, but she only had eyes for her husband. That’s why it’s an American love story, because she loved Claude with her heart and soul.

To me, Claude A. Barnett doesn’t get his dues. He’s the one who got Etta’s career started. He hooked up Etta and Clarence Muse [Car Wash, Porgy and Bess]. Etta worked her magic, she got booked, and she’s off. She never played a maid or a servant role. He also developed this massive media empire, and everyone knew him.

They were really a powerful couple. They were the Beyoncé and Jay-Z of the time. It would be wonderful if somebody could do a film featuring them as the Barnetts. That would be killer. It’s painful because I’m trying my best to get the word out because their story is our history. This is Chicago history. This is world history.

I don’t want [the collection]to go to New York or the Florida Keys. I want the items to stay here in Chicago because the Barnetts are Chicago legends. I see estates all the time. This collection is jaw dropping. The photos, the memorabilia, and, I mean, the clothes.

The difference between Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, and the Florida Keys — I say with an eye roll, but I’m only joking — Chicago is laden with history. Collectors really sleep on the South Side of Chicago, but that’s where the history is. Bronzeville is steeped in history.

You can walk into somebody’s grandmother’s house, look up in her cabinet, and see the collectibles in the kitchen. And I’ve seen this with my own eyes — the old Little Red Riding Hood or Three Little Pigs cookie jars. Then there’s the old Maxwell House or Folgers tins on the stove holding cooking grease. They’re still made out of metal, not paper or plastic. And they don’t know that they can command high dollars on the retail market.

And not just the kitchen, but we go into homes in the poor, downtrodden Black communities, and there’s always, always incredible art. Some of the quilts are museum-quality quilts. When they tore down the old White Sox park, Comiskey Park, they wiped out an entire neighborhood. I communicated with the people in the community and bought a trunk of quilts that came from the Muddy Waters plantation. I then sold it to UCLA. They, in turn, took it on a tour of the United States, which I thought was an incredible thing.

The saddest part of this whole estate business is that people just don’t know what to do when somebody dies. It’s really a shame and sad. When it comes to estates, people unintentionally throw away — we call it in our industry — “the money.”

The family of a famous hat maker from Bridgeview rented a dumpster to get a jump-start on cleaning up and almost tossed away the bulk of a valuable inheritance because they were trying to be helpful. They were throwing away money, so we had to do double work and get it out and bring it back in. So, you must leave the job to the professionals. We understand that it’s a lot on your shoulders, but leave the job to the professionals.

I’m very happy to see that the Barnetts’ important documents have not gotten discarded over the years, because a lot of times, you go into these homes, there’s nothing left. And then you go into some of these homes, these historic estates, and you just see it all.

A lot of times, the family says, “We don’t want anything.” Sometimes we still put together a nice box of mementos because maybe there’s a granddaughter out there. When we liquidated one of the oldest houses in the city of Chicago — over by the United Center — which still had the gas lighting in the walls, the family didn’t want anything. They said, “Don’t send us anything; just FedEx us the check.” But then I started seeing little things, like a single-strand pearl necklace, a little mink stole, a pair of gloves with pearl buttons on the side, and a little French tea set. I located a niece who lived here in Chicago — she couldn’t have been more than 21 — and I gave her that box.

We’ve been doing estate sales for 12 years. We believe everybody has a story, and our job is to get the story told. As former clinicians, Ty and I often counsel clients on how to say goodbye and figure out the best way to appreciate stuff accumulated during a life. We will do the right thing. We will make sure that these documents don’t wind up on somebody’s table at L.A.’s Rose Bowl Flea Market. No offense to the Rose Bowl.

I actually met my husband while completing my practicum for a master’s in psychology from the Adler School. I was his intern. My mother, Helen Rousseau, graduated as an interior designer from Ray Vogue College of Design on the corner of Huron and Michigan when I was a little girl. So, I came by my interest in antiques honestly. We are archaeologists, anthropologists, sociologists, and therapists. We are going through the Barnetts’ archive and we are putting it together, bone to bone, until we build a body.

A Glimpse of a Marriage

EBONY PLAYING CARDS

Claude A. Barnett was a mentor to John H. Johnson, founder of Ebony, which produced these playing cards in the 1960s.

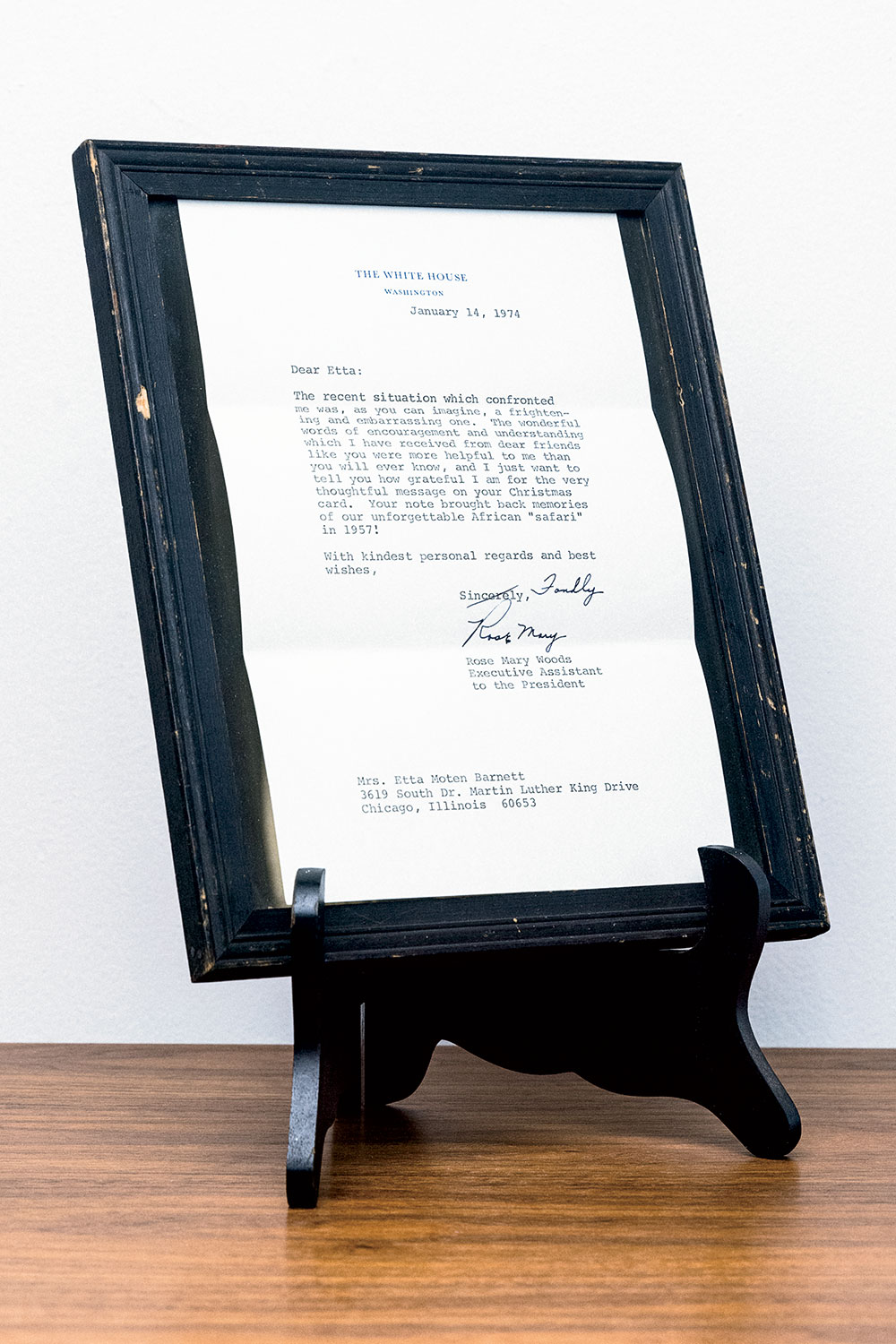

WATERGATE LETTER

Rose Mary Woods, executive assistant to President Richard Nixon, wrote this letter to Etta Moten Barnett on January 14, 1974, to express her gratitude during the Watergate investigation. It reads, in part: “The recent situation which confronted me was, as you can imagine, a frightening and embarrassing one. … I just want to tell you how grateful I am for the very thoughtful message on your Christmas card. Your note brought back memories of our unforgettable African ‘safari’ in 1957.”

THE BARNETTS AT HOME

The Barnetts, both on the left, receive friends at home, sometime around 1945. The Barnetts owned one of the largest collections of African ivory in the United States — still legal then — which included the carved elephant tusk on the table.

A CLOSE-UP

Etta was called “the most beautiful woman I had ever seen in my life” by Sidney Poitier. This portrait was taken in the late 1920s.

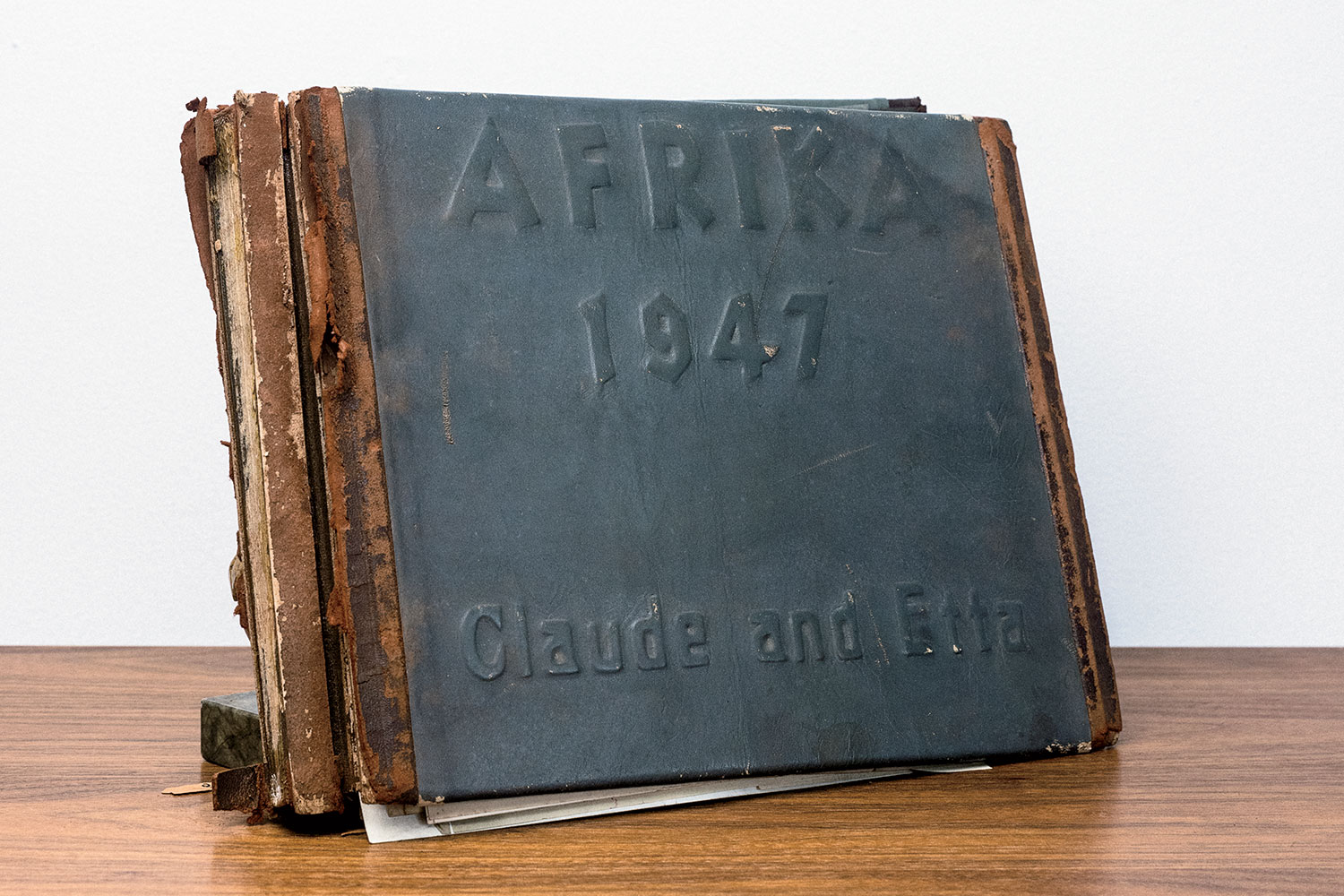

AFRIKA 1947 PHOTO ALBUM

The album chronicles the Barnetts’ Ghanaian travels during the rise of Kwame Nkrumah, who would become Ghana’s first prime minister.

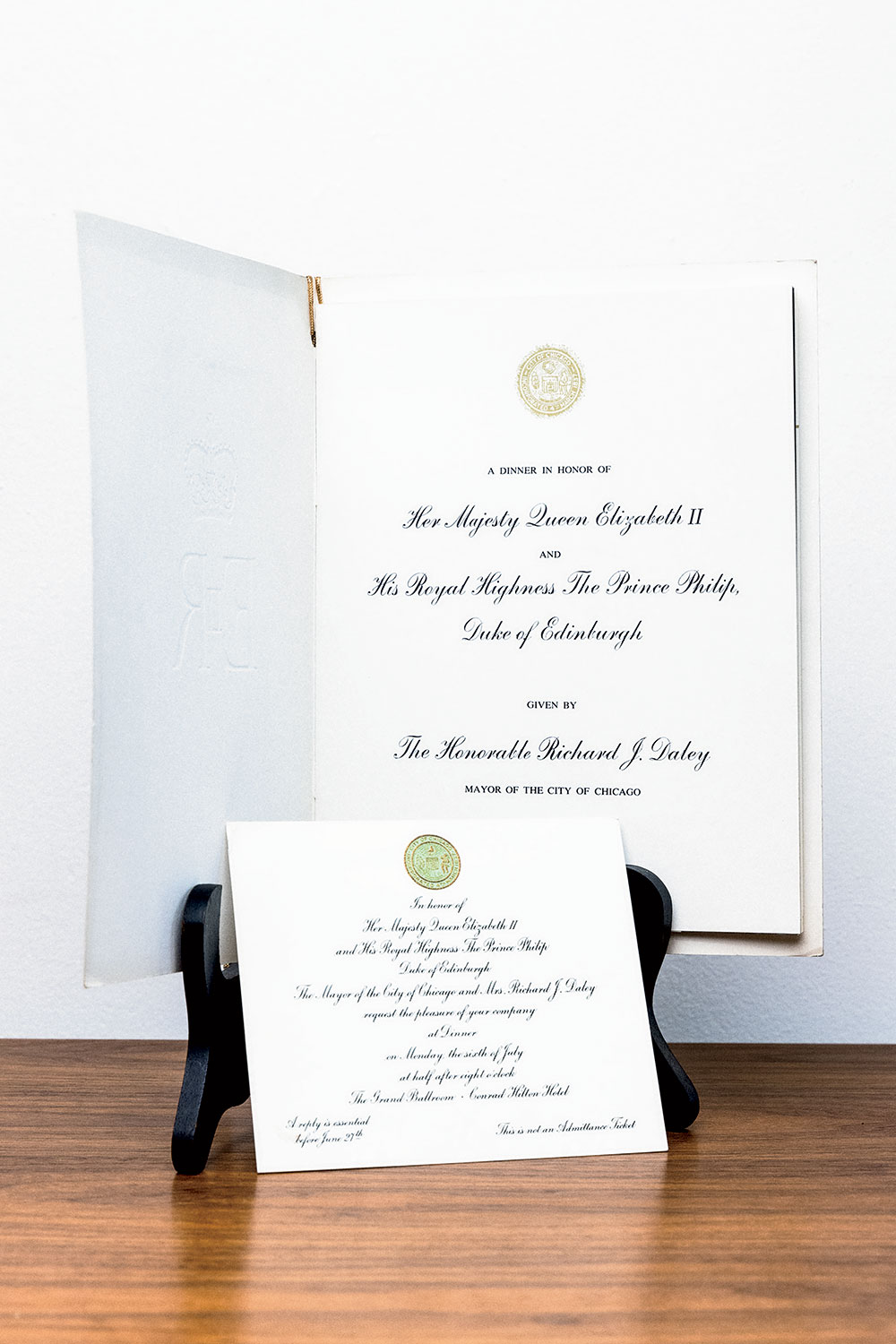

INVITATION FROM QUEEN

The Barnetts were invited to attend a party for Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip at the Conrad Hilton on Michigan Avenue on July 6, 1959.

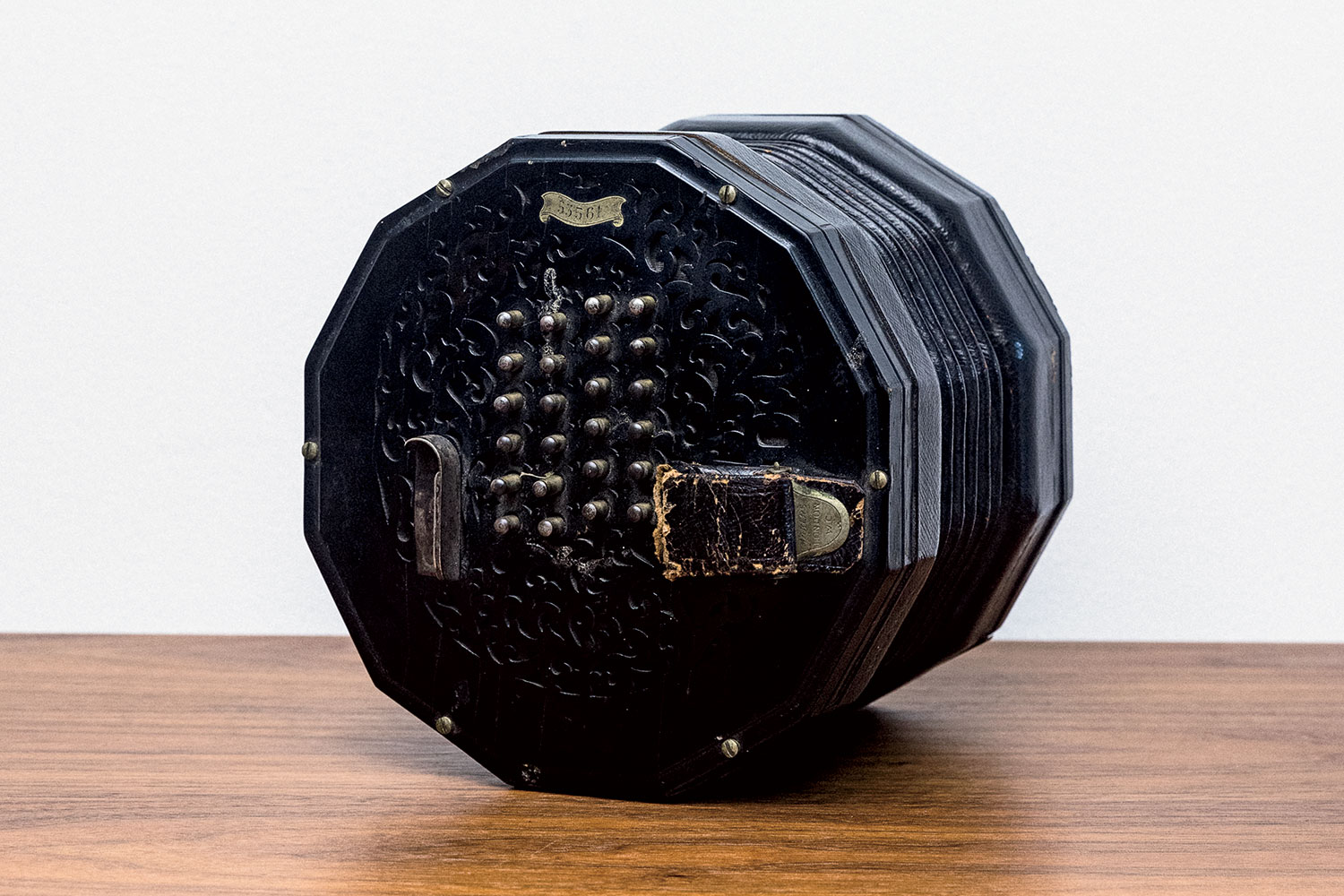

CONCERTINA ACCORDION

Etta owned and played this 1914 concertina accordion, featuring six-fold bellows and ebonized pear-wood ends.

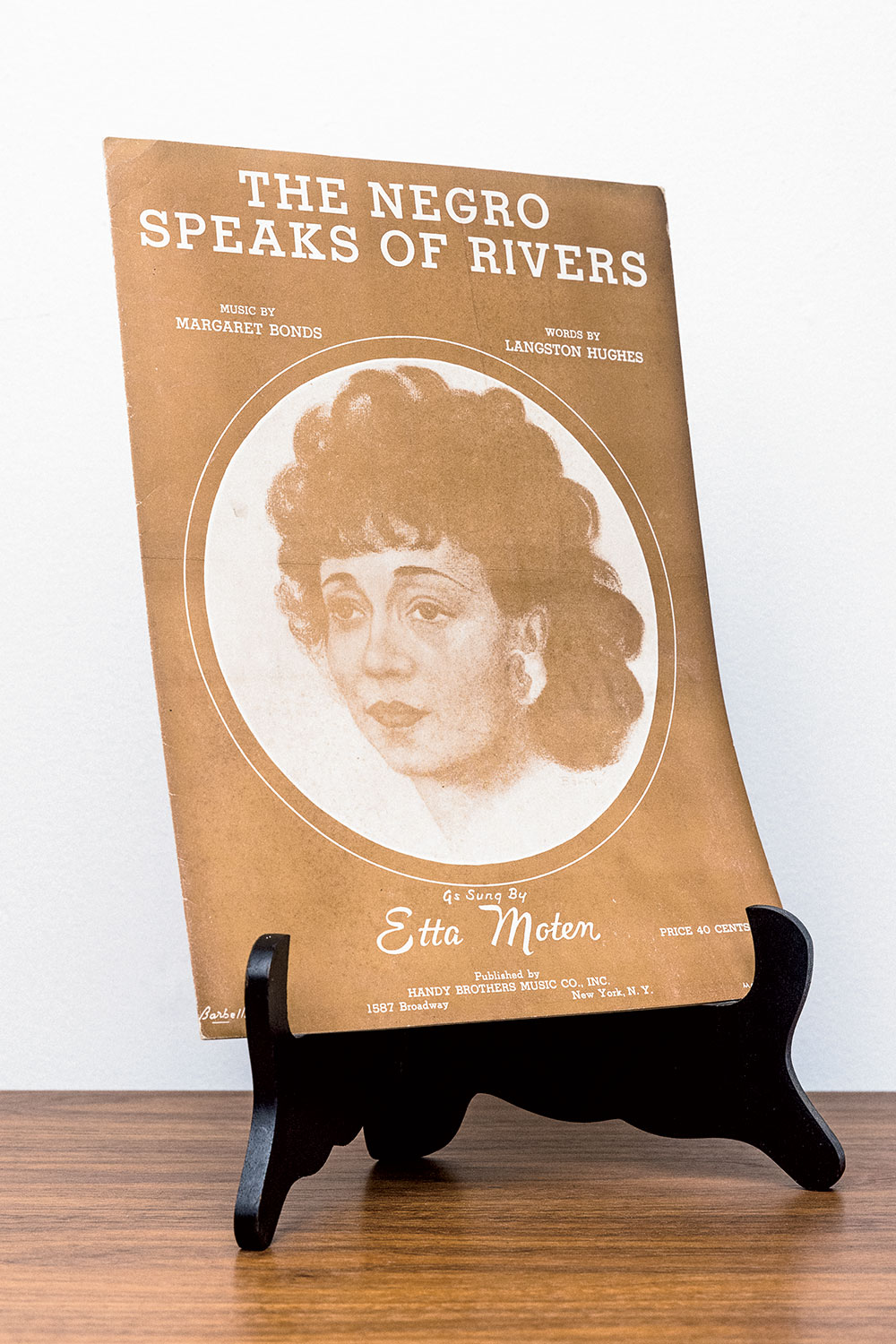

SHEET MUSIC

In the early 1940s, Etta sang the premiere of The Negro Speaks of Rivers, a poem by Langston Hughes set to music by Margaret Bonds.

THE POACHER

This sculpture, acquired during the Barnetts’ travels to Nigeria, Liberia, or Ghana, portrays a legendary figure who goes from village to village, bringing booty to his people. He carries a baby elephant on his head and stands on a crocodile.

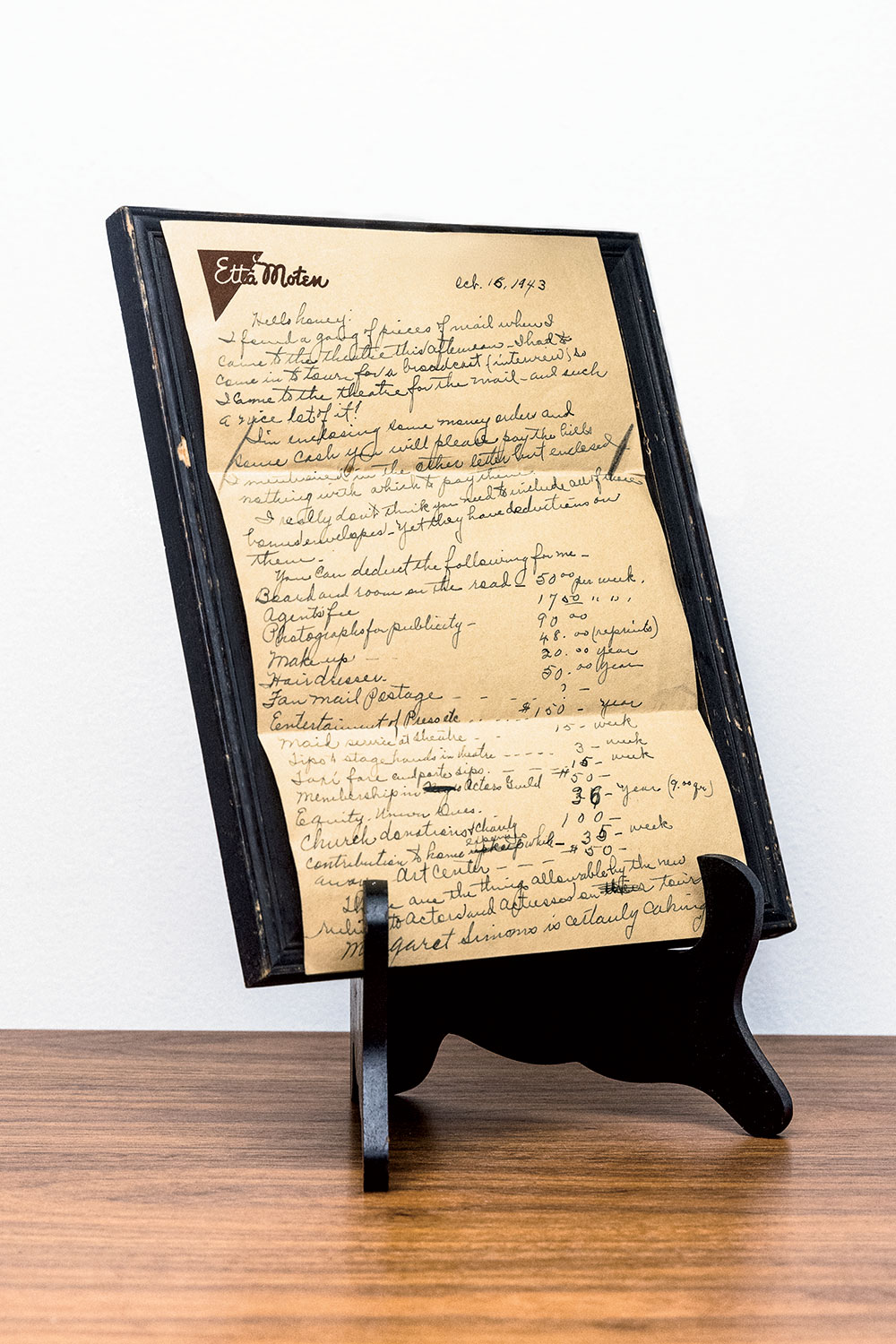

A LETTER FROM ETTA TO CLAUDE

This October 1943 letter written during Etta’s tour of Porgy and Bess begins with “Hello honey” and goes on to outline expenses incurred while traveling, including: $50 per week for board and room on the road; $17 per week for an agent’s fee; $90 for photography; $20 per year for makeup; $50 per year for the hairdresser; and “?” for fan mail postage.