When Otto Frank returned to Amsterdam from Auschwitz after World War II, he was alone, his wife and two daughters having perished in Nazi concentration camps. But Miep Gies, who had helped his family in hiding, gave Frank the papers his daughter Anne had left behind. Among them was the diary he would publish, now among the most iconic of Holocaust artifacts.

For all that was lost in the war and the genocide, there were also precious acts of salvage. With each passing year, new letters and manuscripts and memories surface — insistent reminders of lives, like Anne Frank’s, derailed or extinguished, and of a culture and heritage threatened but not entirely gone.

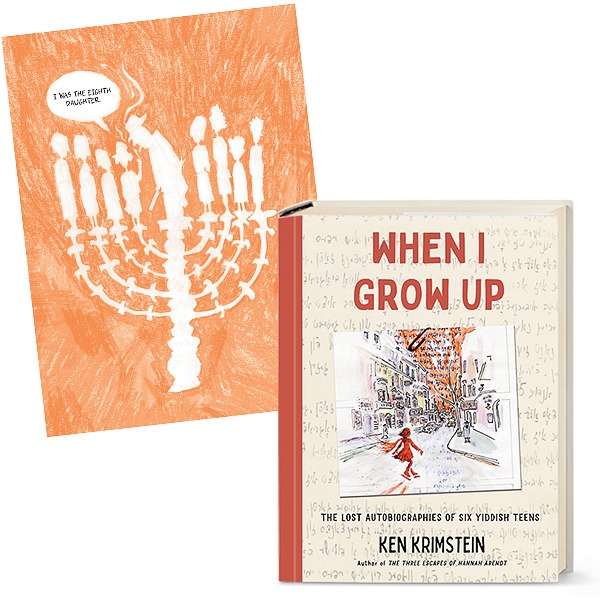

Ken Krimstein’s new graphic narrative, When I Grow Up, derives much of its power from that context. This collection of six tales, adapted from 1930s manuscripts by Jewish youths from Eastern Europe, shows them wrestling with concerns whose contours haven’t changed much over the decades: fractured families, the heartbreak of first love, conflicts over education, and dreams of a better life. That their dreams, shaped by the religious, social, and political currents of the time, were destined to be thwarted — that the writers, in most cases, never would grow up — gives the collection its special poignancy. So, too, do the many twists and turns in the story of salvage and preservation that Krimstein uses to frame these tales.

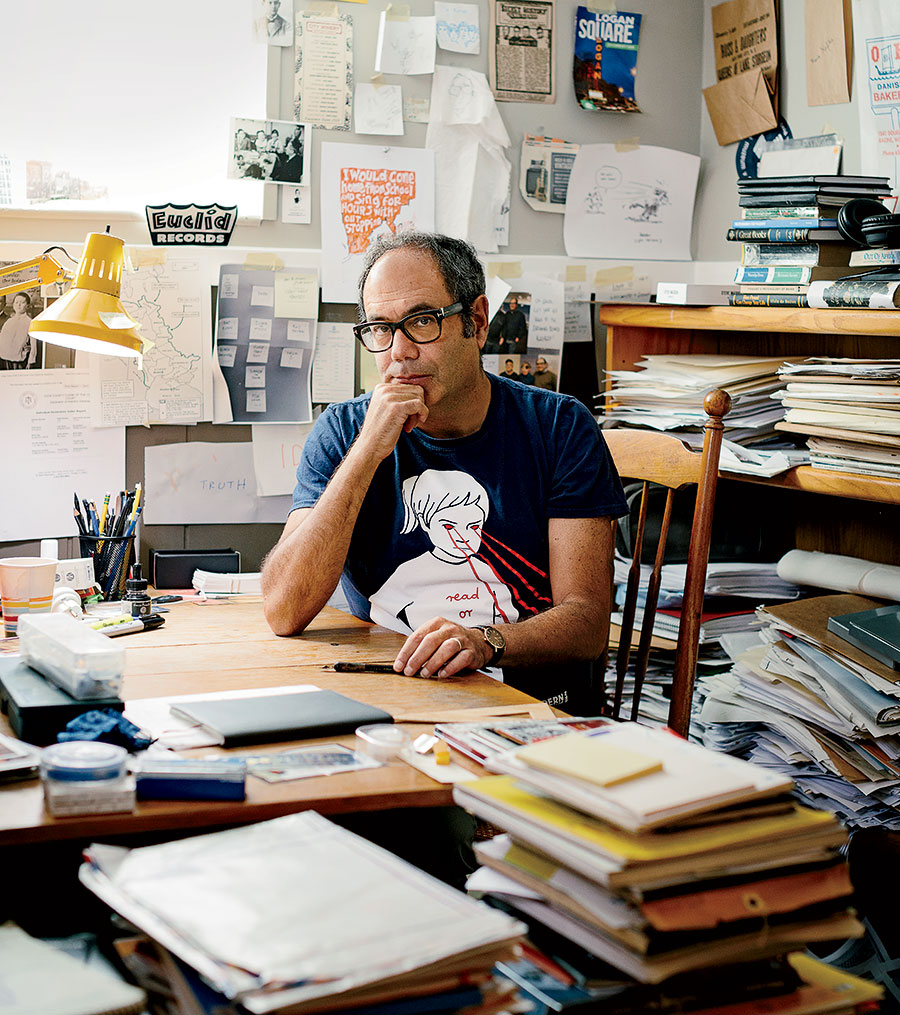

An Evanston resident and New Yorker cartoonist who teaches at DePaul University and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Krimstein leavens the potential sentimentality of When I Grow Up with both his signature wry wit and a raft of scholarly footnotes. These techniques will be familiar to fans of Krimstein’s 2018 graphic novel, The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt. Pushing the limits of the medium, Krimstein envisioned Arendt as a philosophical superhero, illustrating her travails as a refugee, her complicated friendships and marriages, and her groundbreaking analyses of totalitarianism and what she termed “the banality of evil.” He also probed the tension between her inescapable Jewish identity and her doomed love affair with her married mentor, the philosopher — and Nazi Party member — Martin Heidegger. For good measure, he added extensive footnotes and a suggested reading list.

When I Grow Up has in common with Krimstein’s earlier work the pre-World War II European setting and a concern with aspects of Jewish culture and experience. But for all its co-optation of superhero tropes, Hannah Arendt was indisputably an adult narrative. This new book will likely speak to a broader audience, especially teenagers and young adults who can identify with the adolescent angst on display.

It’s not always entirely clear how much Krimstein has enhanced the source material — where the original voices end and his begins. These stories all derive from what he calls, in a prologue, an “ethnographic study in the guise of a meagerly funded autobiography contest” by the Vilna-based organization YIVO (now known as the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research). Launched in 1932, the “contest” — in actuality, three separate competitions — was open to boys and girls ages 13 to 21, he writes. (An 11-year-old included in the book was a presumptuous outlier.)

As is customary in social science research, entrants were permitted to remain anonymous to encourage candor. “Throughout the 1930s,” Krimstein writes, “more than seven hundred entries rolled in from all corners of Yiddishuania,” his neologism for the swath of Eastern Europe where Yiddish was the lingua franca.

By supreme bad luck, the day that the grand prize of 150 zlotys was to be awarded was September 1, 1939 — the date of the Nazi invasion of Poland and the start of World War II. As a result, Krimstein tells us, no YIVO winner was ever announced, no prize given — and all the entries were very nearly obliterated.

How they came to be preserved is an extraordinary story. When the Nazis conquered Vilna, in June 1941, they decided to steal YIVO’s holdings for their own Frankfurt-based Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question. But the Jewish ghetto residents charged with the sorting process smuggled out and concealed as much as they could. For their wartime heroics, they would become known as the Paper Brigade.

When the Soviets retook Vilna in 1944, the brigade’s few survivors unearthed the hidden documents and established the Vilna Jewish Museum. Five years later, though, Stalin, angered by Israeli politics, “ordered the entire contents of the museum pulped in retaliation,” Krimstein writes. But a sympathetic Communist Party official stashed the Yiddish trove in a church — where it was not rediscovered until 2017.

Unlike Anne Frank’s diary, which is concurrent with the deportation of Dutch Jews, the stories in When I Grow Up are not, properly speaking, Holocaust narratives. They are set in an Eastern Europe that has not yet become a cauldron of death. Antisemitism intrudes, for sure, and the writers’ prospects are often limited by gender, class, and custom. But life is not unabashedly grim. While enmeshed in the era’s constraints, these young people worry about quotidian problems.

In “The Eighth Daughter,” a 19-year-old describes the powerful influence of her father, a kosher butcher with literary interests who encourages her passion for reading and writing. After his untimely death, she attempts to say Kaddish, a mourning prayer. A synagogue official shuts her down, declaring: “Don’t you know that a girl’s Kaddish is worth nothing?” She concludes: “Still all these years later, my heart yearns.”

Yearning is, in fact, the collection’s dominant emotion. In “The Letter Writer,” a 20-year-old boy’s studies are cut short by his Jewish background. He reacts by writing letters to the mayor of Tel Aviv, the president of the United States, and the editor of an American Yiddish newspaper. His efforts to immigrate to the United States end up being stymied by labyrinthine visa requirements — and his American uncle’s tax dodges.

“The Folk Singer” tells the story of a 19-year-old music lover whose father descends into alcoholism, steals money, deserts, and leaves the girl and her five siblings destitute. Despite her mother’s steadfastness, the girl still finds herself “overcome with longing” for the parent who abandoned her.

Then there is “The Rule Breaker,” whose author not only entered the contest too young — at 11 — but violated its anonymity with both her name and a photograph. Beba Epstein’s very propensity for rule breaking may have contributed to preserving both her life and her story. The adult Epstein, it turns out, was a member of the Paper Brigade. A conversation Krimstein has with her son propels the author to the city that is now Vilnius, Lithuania, providing the inspiration for this book — another link in the chain of salvage.