This is not as tired as DeMar DeRozan gets, but it’s close. The Chicago Bulls star forward is quietly decompressing in the third row of a luxury SUV driving through Los Angeles, his hometown and where he lives during the off-season. He has just finished the second of two consecutive two-hour gym sessions.

The real exhaustion will come in August, with its three workouts per day, but late July is no slouch. A few friends are along for the ride, and DeRozan breaks his silence when their conversation turns to the ever-growing Mega Millions lottery prize. Yet another drawing had gone by without a winner, and the potential jackpot was now up to a staggering $1.025 billion.

“If I won that,” DeRozan says, “you would never hear from me again.”

It’s a joke — hence the laughter — but his tone seems more wistful than arch. Perhaps I’m reading too much into it. I’m tired, too. I had to get up at 4 in the morning to watch him work out.

DeRozan credits much of his success to the grueling routine he maintains during these so-called off months. “I hate the summer because it’s the hardest,” he tells me. “But it makes the season easier. It’s like, I just got to play and practice? Perfect.”

A normal summer day starts pre-predawn, when DeRozan hauls himself out of bed and makes his way across L.A. County for his first scheduled training session at 5. The freeways are empty, but the drive to the little gym by LAX still takes about an hour. It’s dark, and he shuffles through the rear parking lot wearing a pair of ruby Crocs, briefly raising his drowsy gaze when I compliment his choice of footwear.

“Crocs are the shit,” he says. There is no reason to doubt his sincerity on the matter — he claims to own a pair in nearly every color.

With the exception of a few framed jerseys of famous clients hanging on the walls, there’s not much to suggest that Jason Estrada’s gym is an elite training facility. From the outside, one could reasonably expect it to be an auto repair shop or a bathroom tile showroom. “Everything in here is unassuming,” Estrada says with pride. He’s talking about the equipment, or the relative lack thereof, though he might also be referring to the sleepy 6-foot-6 NBA player loosening up on the ground before him.

“I never tell him what we’re going to do each day,” Estrada says. “He just has to show up. It’s easier if it’s a surprise. He doesn’t have to think about it.”

“It still sucks,” DeRozan says from the floor.

What’s going to suck today, specifically, is some extensive work on the Quadmill. Tucked away in the corner, it looks like a bulky treadmill. Estrada has affectionately dubbed it the Scream Machine, and, seeing my reaction to this phrase, asks if I want to try it out. “Sure,” I say, so as not to look like a dweeb, but Estrada instead tells DeRozan to hop on.

“I thought Nick was going to use it,” DeRozan says with real despair.

When engaged, the once-unassuming Quadmill bucks in a manner similar to a barroom’s mechanical bull, and I thank God that Estrada’s offer was a joke, for I surely would have been thrown from the gyrating platform and through the glass of the framed Michael Strahan jersey on the wall behind it like a stuntman in a western saloon fight.

DeRozan, of course, can handle it. Standing in a semi-squat, he keeps his upper body perfectly still and churns his legs and hips to keep up with the rapid movement, like an Olympic skier flying down a set of moguls. While there are no outright shrieks, the Scream Machine does elicit a cascade of pained grunts.

Estrada has been working with DeRozan for the majority of the player’s career. He is a kinesiologist, and much of his focus is on movement and fluidity. He instructs DeRozan to stand on the Scream Machine sideways and then pantomimes grabbing a rebound to demonstrate how the two actions are similar to each other.

DeRozan stops for a breather, and I ask if he’s able to tell if he’s getting better — whether self-improvement is a conscious act. “You can’t think about it in the moment,” he says. “You don’t wake up on Monday happy about Friday.”

Estrada perks up at this spontaneous and thoughtful axiom. It’s something that could be added to his Write Book, a journal his clients and other gym visitors fill with kernels of wisdom. DeRozan flips to a page which, purely by chance, is one upon which he had scribbled an entry. “That’s crazy,” he says, pointing to what he wrote: “An hour of Jay, an hour closer to greatness.”

“Do you believe that?” I ask.

“I guess,” he says. “I wrote it like nine years ago.”

Last season — DeRozan’s 13th in the NBA and first with Chicago — was, by many measures, the finest of his career. He put up 27.9 points per game, his most ever, as he led a young and promising but oft-injured Bulls squad to the team’s first playoff appearance since 2017. He was named to the All-NBA Second Team and was a legitimate MVP candidate for much of the year, including a frankly absurd period in February when he set a league record by scoring 35 or more points on at least 50 percent shooting for eight straight games. The previous best streak of such high-output efficiency was six games, achieved in 1963 by Wilt Chamberlain, a man who may or may not have been engineered as part of a Manhattan Project–style experiment to set seemingly unbreakable records. Despite DeRozan’s efforts, though, the Bulls faded down the stretch and quickly bowed out to the Milwaukee Bucks in the postseason.

DeRozan’s route to Chicago was circuitous. Drafted by the Toronto Raptors in 2009, he formed a remarkably close bond with his adopted city and organization, but in 2018 he was abruptly traded to the San Antonio Spurs. DeRozan has spoken occasionally about how painful the experience was, a torment exacerbated by the Raptors’ championship-winning run the following season without him. This candor was on display during a 2021 conversation with his friend and fellow NBA star Draymond Green for Green’s web series Chips, when DeRozan described feeling despondent upon learning that he had been traded. “It hurt like shit,” he said. “We’re all expendable at some point.”

“I always tell myself that when something gets harder, you push yourself even more to try to get through it. I hate getting up at 4 o’clock in the morning. Trust me.”

There’s an old saw you’ll sometimes hear from NBA players about the fickle nature of their occupation: “It’s a business.” While that’s generally true and perhaps even reassuring, DeRozan, who turned 33 in August, doesn’t necessarily see it that way. “This is not a job,” he tells me. “We only get so long to play. You’re not a teacher. You can’t do this for 40, 50 years and get your retirement plan at 68. You only get a short window to be able to accomplish this. That’s the challenge and the beauty of it.”

In San Antonio, DeRozan found himself on a team caught between its storied recent history and an undecided future. But he credits the experience with helping him grow as a player, even if his tenure didn’t attract national attention or amount to much success. “San Antonio took me in, and I embraced them,” he says. “But that wasn’t my choice to be there.”

In the summer of 2021, after three seasons in Texas finishing off the long-term contract he had signed with the Raptors in 2016, DeRozan was able to fully explore free agency and have some say in his next stop. He initially expected to join the Los Angeles Lakers, going as far as to say that he considered it a “done deal” at the time. But the move fell through, and the Lakers opted to go a different direction, one that involved trading for point guard Russell Westbrook and his sizable contract. To learn how that turned out, search for “Lakers Westbrook” on Twitter. Or don’t, actually. Just know that it could have gone better.

If this Sliding Doors moment is still on DeRozan’s mind, he certainly doesn’t show it. During our ride through Los Angeles, his driver asks if the Lakers are going to sign point guard Patrick Beverley during the off-season. (Indeed, they did.) “Shit,” DeRozan says. “They’re probably going to try and sign you, too.” (Sadly, they did not.)

DeRozan settled on the Bulls. He joined the team in the second year of an organization-wide rebuild that began with the 2020 defrocking of GarPax, the once-immutable two-headed front office monster otherwise known as Gar Forman and John Paxson. Replacing them as team architects were a pair of new hires, executive vice president of basketball operations Arturas Karnisovas and general manager Marc Eversley, who had been Toronto’s assistant GM when the Raptors drafted DeRozan.

“Chicago had been a struggling organization,” DeRozan says. “It was one of those things where they just hired a new front office and were moving in the right direction. You look at it from the dynamics of them really trying to make a push to be a winning organization again — especially when they brought in Marc Eversley. Having a relationship with him and hearing his vision and what they wanted to go after and accomplish, I knew it wasn’t anything that would waste my time.”

Still, DeRozan’s stellar first season in Chicago managed to surprise even the people responsible for his recruitment. “We’re in the business of identifying talent and projecting out future talent,” Eversley tells me, “but I’d be lying if I told you I thought DeMar would turn out to be the player that he is today. I watched him evolve from this lanky, raw, athletic wing to someone who became the Spurs’ pseudo–point guard. For us, he improved our basketball skill. He improved our basketball IQ. And we needed somebody in the locker room who could provide a little bit of leadership for this young group.”

Helping to ease DeRozan’s transition was head coach Billy Donovan, whom Karnisovas and Eversley hired in 2020 as one of their first moves. DeRozan calls Donovan a “players’ coach,” which is very much a term of endearment. “He values our opinions about everything, first and foremost,” DeRozan says. “There are a lot of coaches who are stuck in their ways. It’s their way or no way. But when you incorporate your teammates and make them feel as one, it makes the job feel a lot easier.”

This feeling is mutual. “I’m a guy who likes to sit down and talk and watch film and meet to get the players’ perspective about things,” Donovan would tell me later. “When I first talked to DeMar about that, he said, ‘The more we meet, the better.’ ”

Donovan replaced Jim Boylen, who had the flair and temperament of an overzealous gym teacher and went so far as to install a literal time clock so his players could punch in and out of practice each day. I ask DeRozan whether Donovan, the “players’ coach,” is the exact opposite of Boylen. “Yeah,” he says. “From what I’ve heard.”

It’s easy to look at the stats and declare DeRozan’s first year with the Bulls the best of his career, but the player approaches the subject with more nuance. “It was my freest season, without a doubt,” he says. “To have a choice, for the first time in my career, and to have it pan out how it did, it was a different sense of freedom — like, This was the choice I made. That was the dope thing about it.”

But that’s all over now. This is summer, the tempore horribilis in which DeRozan is beholden to the cruelties of time, and his early-morning workout grinds on. There are ab drills. Cable-pull wood chops with a special basketball-shaped attachment. Prone back arches. Many more sessions atop the Scream Machine. Skip Bayless is on the TV, and somebody switches the channel to a small-claims-court-based reality show called Relative Justice that grabs DeRozan’s attention. He spends his time between sets glued to the ongoing arbitration. Outside, the sun finally starts to rise.

The workout ends with some deep stretching, and then we drive north for more than an hour to reach the next destination: yet another gym. DeRozan insists on sitting in the SUV’s third row. “I don’t like having people behind me,” he says. I ask him about movie theaters. “Last row. Always.” That’s where he sat the previous night during a showing of Jordan Peele’s Nope. (He enjoyed it.) It’s somewhat unfortunate, then, that his job requires him to sit for stretches with thousands of spectators packed behind him.

We arrive at an airy, warehouse-like facility with a basketball court, and DeRozan switches from his Crocs to a pair of Nikes. The leader of this second workout session is Johnny Stephene, a dribbling consultant who briefly played professional ball in Mexico before a leg injury forced him to pursue a new career path. Stephene instructs DeRozan to warm up by taking a few one-footed shots from about 10 feet out. He clanks his initial three attempts, which, in all my years watching him play, might be the first time I can recall seeing DeRozan miss three midrange jumpers in a row.

I’m not the only one. There’s a clip from a shootaround before the 2022 All-Star Game in which the Dallas Mavericks superstar Luka Doncic pulls DeRozan aside and playfully asks, “Did you ever in your life miss a midrange shot?”

“Sometimes,” DeRozan responds.

In this hot, near-empty gym, it’s more than a tad surprising and more than a little amusing to watch DeRozan take advice on how to dribble into his midrange jumper. This is not a knock on Stephene — it’d be wild to see anyone instruct DeRozan on this particular prowess. No one made more midrange jumpers during the 2021–22 season than his 348, and it wasn’t even close: Kevin Durant, the second-most prolific scorer from that range, made only 226. (It’s worth noting that, with the rise of analytics, DeRozan’s favored shot is now considered the most inefficient in the sport and has fallen out of favor.) DeRozan is quite literally the most accomplished midrange scorer on planet Earth, so this is like watching a great white shark take seal-eating lessons from, well, someone who isn’t a great white shark. Even so, DeRozan remains attentive and dutifully follows Stephene’s instructions.

“I started out with Johnny eight, nine years ago,” DeRozan says when I ask him how he learned to trust others with improving his game. “He was just a regular guy trying to make something happen.”

But why would DeRozan listen to a regular guy?

“Shit,” DeRozan says. “I was just a regular player.”

Stephene switches to pure dribbling drills, and DeRozan bounces two basketballs behind his back while doing lunges from one end of the court to the other. Though this specific skill is unlikely to be called upon during an NBA game, it never hurts to be prepared. Last season, DeRozan assumed more than his fair share of ball-handling duties, a responsibility that became especially pronounced late in games, when the Bulls would inevitably turn their offense over to the veteran scorer. Opponents knew who was going to get the ball in such moments, but that hardly mattered — DeRozan still averaged 8.4 points in the fourth quarter, more than any other frame.

“The ends of games slow down, they quiet down, for him,” Donovan says. “That’s not a normal thing that guys do instinctively. I mean, maybe there are some guys who are better than others, but he works at it. He comes back in almost every single night [after games] to shoot. There’ve been times when I’ve come back just to watch what he does. It’s really impressive. Meticulous.”

Eversley finds himself watching in awe, too: “DeMar plays with a cadence of a veteran. The game is never too fast for him. He never lets the defense speed him up. It’s incredible. He always gets to his spots. His ability to break down a defender and still get off his shot, it’s something to marvel at.”

“Gets to his spots” — that’s the basketball adage that best explains how DeRozan manages to make it all look so easy. He’ll slash past his man, stop on a dime, and then rise over an outstretched hand to sink a jumper. Then he’ll do it again. And again. And again. With increased frequency, the sequence becomes all the more astounding, calling to mind viral videos of people who are so extraordinarily good at their jobs — a truck loader neatly stacking kegs at a furious pace; a farm worker bundling crops with unerring precision — that they manage to transform a rote task into high art.

“It’s repetition,” DeRozan explains. “I drill. Understanding my angles, separation from guys, just every way possible on the floor. A lot of that comes with time, with doing something over and over and over and over and over.” DeRozan has a knack for coming up with compelling analogies on the fly, and here he provides a relatable one: “It’s kind of like how you can be inside your bedroom with the lights off, but you still know where you need to go. You have a comfort because, unconsciously, you’ve walked through it thousands and thousands of times. And so, when you get up in the middle of the night, you don’t need to turn on the light.”

DeRozan continues to pay his respects at the altar of repetition and is now drenched with sweat. There is more dribbling and shooting before Stephene initiates the final drill, which is supposed to mimic high-pressure end-of-game situations. Stephene tosses the ball to DeRozan and yells a number — one, two, or three — that denotes how many dribbles he must take before getting his shot off. Stephene is also playing defense, along with an assistant who applies the double team. They play multiple games to 13, with the defenders getting points whenever DeRozan misses. While I lose track of the exact scores, I do know how many points DeRozan had at the end of each round: 13.

Notable during this drill is the manner in which DeRozan racks up a chunk of his points. He takes a sizable number of step-back 3-pointers, a move that is de rigueur in the modern NBA but hasn’t been for DeRozan. He attempted only 1.9 a game last season. For comparison, Nikola Vucevic, the Bulls’ 6-foot-10 center, averaged 4.5. Is this long-range step-back a shot that DeRozan plans to incorporate this season?

“I always try to add something,” he says. “A lot of times you don’t necessarily know what it is. You work on countless things. You add it to your package. Over time, over the summer, you try to get comfortable with it. I like it to become second nature. So if I’m ever in a moment and something is called for, it’s not an uncomfortable feeling.” In other words, if he finds himself in a dark room this season and has to shoot a step-back 3-pointer, he won’t stub his toe.

The drive home after DeRozan’s second workout is mercifully short. In his backyard, which looks out on a rolling tract of drought-scorched canyon, he continues to talk about the dichotomy between comfort and discomfort and how the latter must be endured to facilitate the former. “I always tell myself that when something gets harder, you push yourself even more to try to get through it. I hate getting up at 4 o’clock in the morning,” he says, briefly rising from the near-supine position he has taken in his patio chair. “Trust me.”

Behind him, in the pool, one of his four daughters is taking a swim lesson. He occasionally cranes his neck to see how it’s going, and her apprehensive shrieks eventually turn to giggles.

When DeRozan was 14, his father, Frank, entered him into the Drew League, a legendary pro-am basketball tournament in South-Central Los Angeles. “My dad knew all the older guys. It was kind of like, ‘Get your ass out there.’ It was tough. Back then it was dudes who were, like, grown men. They didn’t give a damn who you was. But it was one of those things that was needed. It went a long way. You would see the separation when I played in high school.”

DeRozan still tries to participate in the Drew League whenever his schedule permits. He teamed up with LeBron James for a game this off-season, and NBA TV bumped a Summer League broadcast to air the exhibition contest, in which the pair of superstars eked out a 2-point win over a squad of former college players. During the game, DeRozan got in a heated exchange with an opponent who was playing handsy defense. The video clip made the rounds online with headlines like “DeMar DeRozan Was Ready to Fight Trash Talker in Drew League.” DeRozan, meanwhile, loves that the defender pushed him so hard. “I think it was a great moment,” he says. “Confrontation isn’t a bad thing during sports. It’s exciting. It brings out the best. Who am I? I’m never too big to get involved in confrontation.”

Later in the summer, DeRozan invited third-year Bulls forward Patrick Williams to stay at his house, join his early-morning training sessions, and participate in Drew League festivities. It’s indicative of the veteran’s approach with younger teammates. “The best example I can give you,” Donovan says, “is when the rookie Ayo Dosunmu got his jersey retired [at the University of Illinois] and DeMar drove two hours to go be there with him. He doesn’t have to do things like that.”

Dosunmu, a second-round pick last year who grew up in Chicago and graduated from Morgan Park High School, recalls the interaction that led to DeRozan joining him in Champaign. “He just asked me where I was going. I told him, and he said, ‘All right, I’ll be there.’ And he came. It meant a lot, because that was before we were really cool.”

“I know the value of appreciating the young guys,” DeRozan says. “Ten years from now, I want him to do the same thing for somebody else.”

While reserved by nature, DeRozan has made an effort to be more open with his teammates, something that hasn’t gone unnoticed by those who know him. “When DeMar came into the league,” Eversley says, “he was this shy, quiet kid from Compton. Over the years, I’ve seen him find his voice. At times last season, when things didn’t go well, whether it was at practice, a team meeting, the meal room, he would speak up. You don’t have a lot of guys who do that in today’s NBA.”

That takes some of the load off Donovan. “With the young guys,” the Bulls’ coach says, “a lot of times they’ll feel like a player of that caliber is unapproachable. But DeMar is as approachable as you could ever possibly want.”

“When DeMar came into the league,” GM Marc Eversley says, “he was this shy, quiet kid from Compton. Over the years, I’ve seen him find his voice.”

Dosunmu agrees. “He’d always give advice on how the season would go. He doesn’t have to do that. He’s a vet. It didn’t benefit him in any way, shape, or form, but he took time out of his days to share that with me.”

Maybe that’s because DeRozan has sought guidance himself. Midway through his professional career, he found himself contending with persistent emotional pain. It was depression, and when he tweeted, in 2018, that it was “getting the best of” him, he became the first NBA player to speak publicly about mental health in such blunt terms. His candor encouraged others, including the Cleveland Cavaliers’ Kevin Love, to come forward with their own tales of such struggles. The NBA and its players’ association ultimately instituted league-wide access to therapy.

“Anytime anyone expresses about mental health, that says a lot,” Dosunmu says. “For him to do that, to not just bring awareness to himself but to the whole league, that just shows how tough he is.”

DeRozan’s teammates know they can talk to him about their own issues. “You let it come naturally,” he says of these conversations. “Athletes enter a situation where we have to adapt to fame and money so quick, you lose sight of yourself at times. This is not just a basketball thing — this is a life thing. If I could help in any type of way, that’s something that motivates me.”

When DeRozan first entered the NBA, he found motivation by looking at the established stars — that era’s DeRozans. “I was one of those guys who was like, I wanna come for his spot. Then, after a few years, you realize that all these new guys are thinking the same thing [about you]. You’ve got to work that much harder. That’s the beauty and challenge of wanting to continue to make the sacrifices you’re going to make.”

Much like comfort and discomfort, beauty and challenge are irrevocably entwined for DeRozan. For now, he’s happy to be miserable during the summers; he knows that it’s not going to last forever. “If I ever get to the point where I don’t want to make those sacrifices, I just won’t play anymore. I don’t want to embarrass myself or shortcut the game. That’s my view of it. I’ll just try to find different ways to be uncomfortable.”

The previous day, I observed DeRozan explore a new form of discomfort: filming the pilot for Dinners With DeMar, his interview show. The shoot took place in the private room of a Brentwood steakhouse and featured Draymond Green as the inaugural guest.

“Anytime anyone expresses about mental health, that says a lot,” teammate Ayo Dosunmu says. “For him to do that, to not just bring awareness to himself but to the whole league, that just shows how tough he is.”

With his own successful podcast and extensive time behind the NBA on TNT desk, Green is an entertainment empire unto himself, and when DeRozan flubs an early question, the seasoned media mogul assures his host that they can cut it out later. This helps DeRozan settle in, and the conversation quickly picks up steam.

Their discussion vacillates between humor, commentary, and harrowing confession. DeRozan opens up about his childhood in Compton and how he would dress in layers because he never knew when he’d get a chance to shower next. He talks about losing his father in February 2021 after a long bout with illness, using two-day breaks during his final season with the Spurs to fly back to Los Angeles for visitations that, at times, had to be made through a hospital computer screen due to COVID restrictions. DeRozan and Green discuss using basketball as a safe haven and the fear of knowing that their careers won’t last forever. Will they be able to handle what comes next? To be, as DeRozan says, “a human being in the next life”? This show, I gather, is a small component of such existential preparations.

Podium Pictures, the production company behind Dinners With DeMar, which doesn’t yet have a home on a network or streaming service, describes it as a documentary series “focused on breaking the stigma of mental health through the power of athletes and storytelling.” It’s a well-meaning plug that actually undersells the novelty of the show’s approach, at least from what I saw. When DeRozan and Green talk about things like mental health, they manage to avoid Pollyannaish, PSA-style platitudes and instead discuss the subject with frank practicality. Like when DeRozan explains that he had to go through three or four therapists before finding one with whom he could develop an honest rapport. Green responds, with some astonishment, that no one ever talks about “that stuff,” meaning the nuts and bolts of what it’s really like to seek help.

Though it took him a while to get comfortable with a therapist, the calm that DeRozan found in those sessions led to an improved sense of living in the moment, both during his day-to-day life and on the court. “A lot of it is mentality,” he tells me in his backyard. “I’m just as comfortable failing as succeeding. This may sound crazy, but there’s really no pressure. Two things can happen: You either make the shot, or you miss it. That’s just what it is. If I miss it, I’m not going to go to jail. Don’t overthink it. Nothing’s ever perfect.”

I ask if he got nervous during the filming of his pilot. “I think it’s exciting,” he says. “You don’t get to do too much new stuff at this point because you try to be locked in. Obviously, you have your main priorities — your personal life, being a father — but I was at a point of feeling comfortable and I wanted to try something new.”

We’ve both been awake since a God-awful hour, but only one of us has been physically subjected to a pair of intense workouts. Slumped in his patio chair, DeRozan looks like someone in the last row of a red-eye flight struggling to recline. Still, he gamely continues answering my questions. We discuss the moment he began to consider himself a veteran (“When the young guys start calling you ‘OG’ ”), his favorite young players to watch (“I’m a big fan of Josh Giddey from OKC; he’s so creative at doing so many things offensively”), and his go-to Chicago restaurant (Ocean Prime). I ask whether last year’s success will raise expectations for the coming season. “I mean, yeah,” he says. “The goal is to not just go out there and play. It’s to be better.”

The question may have been obvious, but it was asked at a moment when he’d otherwise be napping. Once again, he had pushed himself beyond discomfort.

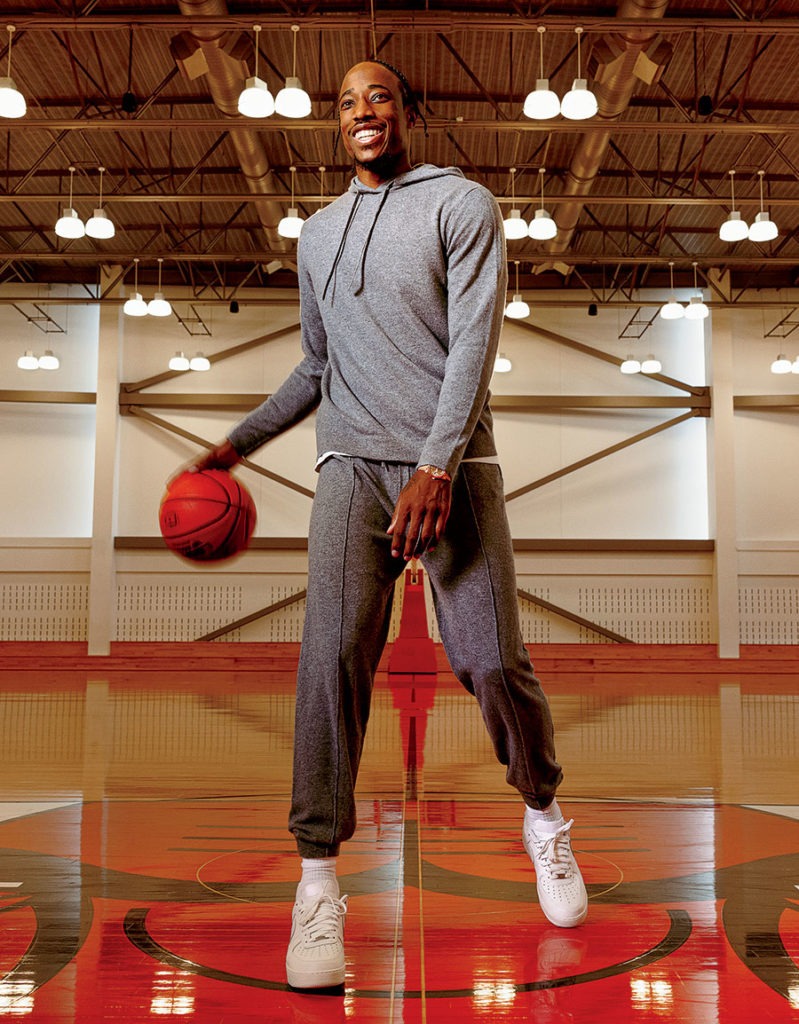

Fashion Styling: Jessica Moazami. TSE cashmere hoodie and sweatpants, Neiman Marcus; A.P.C. blouson jacket, Neiman Marcus; cotton jersey tee, Nike. Grooming: Denise Ferguson