SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO, 1976

Wilfred Benítez stands in the middle of a crowded ring at Hiram Bithorn Stadium, one of his home island’s largest venues. He’s wearing a robe with his name stitched on the back, awaiting the judges’ verdict in his junior welterweight title fight against reigning champion Antonio “Kid Pambele” Cervantes of Colombia. For 15 rounds, Benítez displayed the footwork of a salsa dancer and evaded nearly every one of Cervantes’s jabs, showing a defensive acumen that will earn him the nickname El Radar.

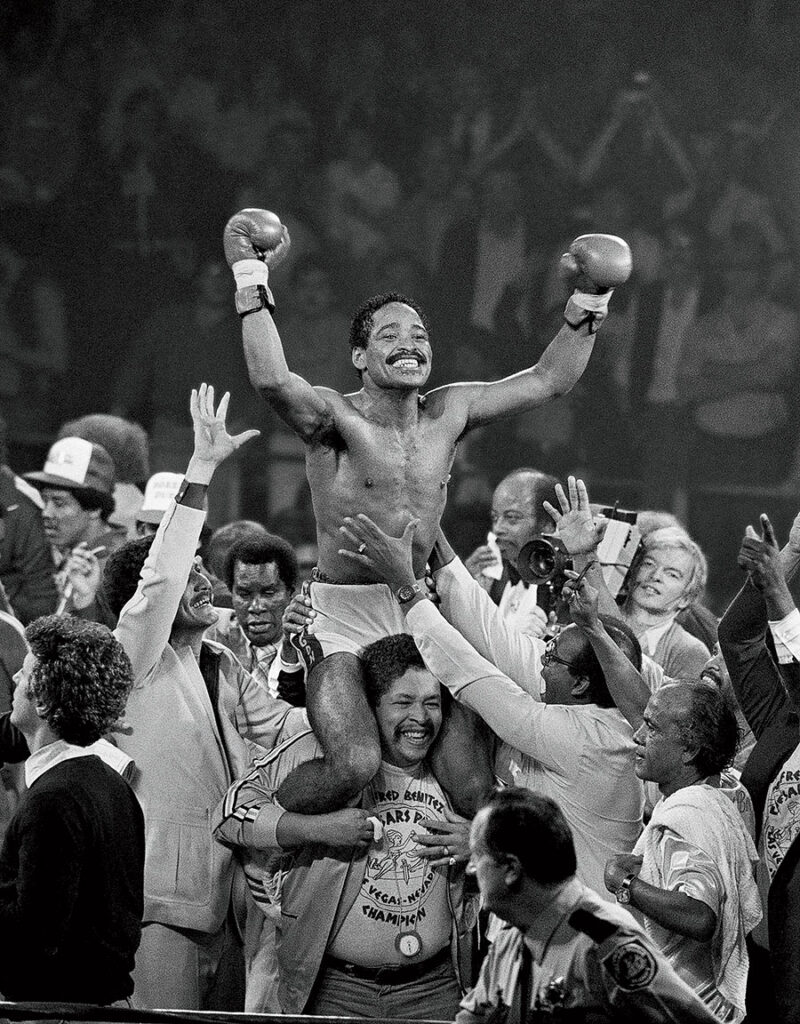

When the ring announcer declares him the winner in a split decision, Benítez raises his fists in triumph. His cornermen lift him high above the crowd and set a sparkling paper crown on his head. The theme to Chico and the Man, sung by Puerto Rico’s José Feliciano, blares in the stadium. At 17 years old, Benítez has just become the youngest world champion in boxing history — a record that will never be broken, now that 18 is the minimum age for a professional fighter.

“I feel happy, because since I was born, I have dedicated all of myself to boxing,” Benítez tells a TV broadcaster as his fans mill around the ring. “I dedicate this fight to Puerto Rico, Colombia, and all the countries that saw this fight. I dedicate it to my mother and especially to my father, who was the one who went through all the trouble for me.”

Three years later, in the same stadium, Benítez, who’d moved up in weight classes, would win another title, the welterweight championship, from Carlos Palomino. Howard Cosell, calling the fight for ABC, would praise the victory as “a sterling boxing demonstration.” Benítez, he would say, was “quicker with his hands, quicker with his feet.”

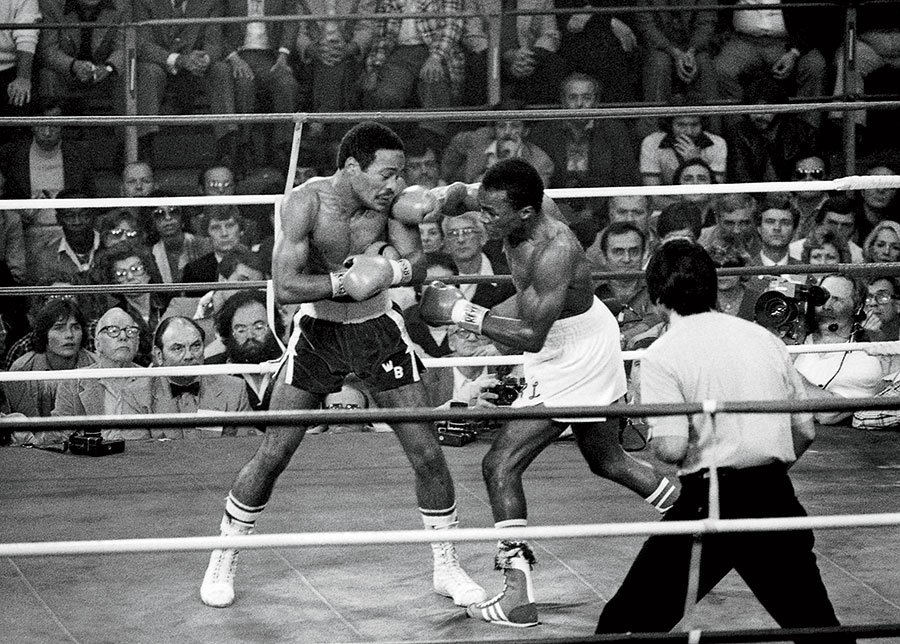

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, after the decline of Muhammad Ali, the welterweight and middleweight divisions were the most glamorous and competitive in boxing. They were dominated by the Four Kings: Roberto Durán, Marvin Hagler, Thomas Hearns, and Sugar Ray Leonard. To many boxing fans, though, Benítez was the fifth king. Ten months after defeating Palomino, he lost the title to Leonard, but he beat Durán and went the distance against Hearns. He won championships in three weight divisions.

Benítez earned millions of dollars as a boxer — $1.2 million alone for fighting Leonard (at the time the biggest purse ever for a nonheavyweight) and even more for Durán and Hearns. Puerto Ricans paraded through the streets of San Juan in his honor. But like so many fighters, he fought too long, pursuing dwindling purses that were still more generous than anything he could have earned without using his fists. After a 1986 bout in Baltimore, a doctor detected neurological damage and warned him to retire. Most states in the U.S. banned him from boxing, so he wandered the world looking for a fight: first in Argentina, finally in Canada, where he lost a decision to a no-name club fighter. After that last match, he returned home to Puerto Rico, shuffling slowly, slurring his words, showing signs of dementia pugilistica. Eventually, his condition would turn him into an infant in an old man’s body — speechless, confined to a wheelchair, dependent on an older sister and her husband to meet his every need.

CHICAGO, 2023

It’s Friday afternoon, and Yvonne Benítez is getting her little brother ready for his monthly visit to the doctor at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Yvonne’s husband, Efraín Crespo Díaz, hooks a swing lift to the sling on which Wilfred lies and ratchets him out of the hospital bed that dominates the living room of the apartment in the Humboldt Park greystone where the former champion has lived for the past five years. Efraín lowers Wilfred into his custom-made wheelchair, taking care to set his urine collection bag in his lap.

On a windowsill, a framed photo of Benítez at 17, his arms raised in celebration after winning the welterweight title, is flanked by a pair of boxing gloves — reminders that the 65-year-old man in the chair, groaning, sticking out his tongue, lifting a gnarled hand, once had the fastest fists in the fight game. Also in the narrow room is a table cluttered with figurines of the biblical Three Kings and a stuffed bear with “Kind People Are My Kind of People” stitched on its belly. A Puerto Rican flag droops on the wall behind the big-screen TV.

Wilfred registers no reaction, other than to look in the direction of his big sister’s voice. He cannot speak. He cannot walk. He wears a diaper because he cannot control his bodily functions. A tube protrudes from his belly because he cannot feed himself.

Yvonne eases the feet at the ends of Wilfred’s withered legs into padded boots: After a recent hospital stay, Wilfred came home with a sore on his left foot. To make sure she never misses a call regarding his medical treatment, Yvonne wears her cellphone on a lanyard around her neck. Now she uses it to summon an Uber minivan and call 911 for assistance getting Wilfred down the steep, cracked front steps.

“Good afternoon, fire department,” Yvonne says. “Will you help me please go down the stairs with my brother? He’s in a wheelchair.”

Yvonne then straps a mask over her brother’s face.

“Wilfred, I know you don’t like this, but I have to put it on you,” she says. “I put it on so you can breathe.”

Wilfred registers no reaction, other than to look in the direction of his big sister’s voice. He cannot speak. He cannot walk. He wears a diaper because he cannot control his bodily functions. A tube protrudes from his belly because he cannot feed himself.

A short, stout woman with a calm, gentle voice, Yvonne, 72, retired as a payroll supervisor for the University of Puerto Rico’s medical school. Caring for Wilfred now consumes her life. She wakes every morning at 5 o’clock to administer his medications and doesn’t go to sleep until midnight, after she has settled him into his bed with a tablet playing the salsa music that soothes him. In between, she bathes him, shaves him and trims his mustache, rubs his chest, moves his arms and legs to prevent them from atrophying, and feeds and gives him medicine through a tube in his stomach. Yvonne leaves the apartment on Francisco Avenue only to go to the grocery store or pharmacy or to accompany Wilfred to the doctor. It’s no sacrifice, she says: “I don’t regret taking care of him. He’s like my baby.”

Wilfred demands of Yvonne the same attention that a newborn does of its mother, but Wilfred will never grow up to take care of himself. He will always be this way, and Yvonne will stay with him.

For as long as she can remember, since well before her brother was in this state, Yvonne has viewed Wilfred as her “baby doll,” someone she needed to look after. When he was 7 and she was 15, they moved with their family from the Bronx, New York, to Carolina, Puerto Rico, a suburb of San Juan. There, their father, Gregorio, began schooling his four sons in the science of boxing. Wilfred’s older brothers Gregory and Frankie had brief prizefighting careers, but nothing like that of Wilfred, the youngest, who had the quickest hands, the quickest feet, and the quickest reflexes, ducking and sliding from every punch.

“You couldn’t hit him,” says Johnny Turner, who lost to Benítez by technical knockout in 1980. “You couldn’t touch him. I caught one shot. In the fifth round, I caught him with a perfect right hand. He’s the only guy who ever hurt me in the body. He was throwing body shots.”

Benítez was not known for his punching power. He was, says boxing historian Thomas Hauser, a “finesse fighter,” bobbing and weaving until he could set up the perfectly timed jab. Harold Weston, who fought Benítez twice — one draw, one loss — calls him “the Bible of Boxing,” a title Benítez gave himself as a young fighter, because he knew every aspect of the sport. “A majority of the fighters are just one-dimensional,” Weston says. “They know one way of fighting. That’s all they do. Benítez could change up. He could go into a slugfest, then turn into a boxer. Not many fighters can do that.”

Despite his skills, Benítez lacked discipline. He preferred partying to training. After he won the welterweight title from Palomino, says Weston, “he thought he ain’t got to worry about drinking, he ain’t got to worry about having sex and all that before a fight. If you don’t toughen your body up, when you do get those hits, your body can’t absorb those punches. They really stay in your system, where they make damages to your head and your body. He paid the price for not training.”

In his autobiography, The Big Fight: My Life in and out of the Ring, Sugar Ray Leonard related a story about visiting Benítez in a nursing home in Puerto Rico after both of their careers were over. At first, Benítez didn’t recognize Leonard, but as they watched their 1979 bout together, he remembered the man who dealt him his first loss in his 39th fight and took his welterweight belt.

“Su … gar, Su … gar,” he said slowly, almost in a whisper, Leonard recounted. “I want … you to know … that I no train for that fight.”

Benítez did train hard, though, for the 1982 fight to defend his title against Durán, who had lost only once in the previous 10 years — to Leonard. By that point, Benítez had moved up in class to super welterweight and won the belt from Maurice Hope, making him the youngest fighter to win world titles in three divisions. To prepare Benítez for Durán, promoter Don King sent him to Chicago to spar with a local fighter named Luis Mateo, who was a top 10 contender but never a champion. “The promoter said I had the same style as Durán and could help him,” Mateo recalls. “I’m a brawler.”

For three and a half months, the two fighters sparred at the old U.S. Arena, at Division and Damen in Ukrainian Village. They became close friends. Benítez took Mateo to Michigan Avenue and bought him $900 worth of clothes. “Do I look homeless?” Mateo joked to him. After Benítez wound up beating Durán to improve his record to 44-1-1, he called Mateo to thank him.

In his next fight, Benítez lost the title to Thomas Hearns, whose long arms were able to penetrate El Radar’s defense. Benítez, then 24, would never wear a championship belt again. He fought a succession of lesser-known fighters, losing almost as often as he won. In 1986, in Baltimore, Benítez fought for a $10,000 purse against Harry Daniels, a middleweight whose career record was 16-37-1. Benítez won by unanimous decision, but his reflexes were noticeably slower. The Washington Post reported that Benítez was tentative, lacked aggression, “sleepwalked through the early rounds,” and “did nothing to dispel suspicions that his career is on the decline.”

The doctor who examined Benítez after the fight was concerned. “He told me not to box anymore, but I’ll go somewhere else to box,” Benítez told the Post. “This is my life. They can’t treat me like this. I’ll fight again.”

Benítez set out for Argentina, where he would lose to middleweight Carlos Herrera by technical knockout in seven rounds. By then, Benítez was no longer being trained by his father, who had broken with his son because he disagreed with his choice of a wife. (In 1983, Benítez had married Elizabeth Alonso, whom he had known since they were children.) After the fight, as Benítez told it, the promoter left the country with the boxer’s passport and purse, stranding him in Argentina. (The promoter claimed Benítez chose to stay in Argentina.) For a year, he lived on the streets of Buenos Aires, panhandling, crashing with strangers, running through the streets until he collapsed. Benítez’s wife reportedly told him not to come home without his $25,000 prize. Finally, someone recognized him and notified the Puerto Rican government, which dispatched its secretary of sports and recreation to bring him home just before Christmas 1987.

When Benítez returned from Argentina, “he couldn’t say his name like usual,” recalls Yvonne. “He couldn’t talk like you and me. He could repeat words.” Even so, “he never accepted his condition. He didn’t think there was a problem.”

But his mother, Clara, did. “Wilfred, this must stop!” she scolded him when she noticed his stuttering and forgetfulness. “No more. This boxing must stop!”

The Puerto Rican Boxing Commission revoked Benítez’s license but put him to work training aspiring Olympians. For the next two years, he stayed out of the ring. In 1989, doctors confirmed Benítez’s symptoms were consistent with chronic traumatic encephalopathy. (The disease can only be definitively diagnosed posthumously.) Once known as dementia pugilistica or “punch-drunkenness,” CTE affects as many as 40 percent of retired fighters, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Its symptoms include memory loss, difficulty planning or carrying out tasks, aggression, depression, and motor neuron disease, which hinders walking, speaking, swallowing, and breathing. A progressive disorder, CTE cannot be treated, and its effects, which often lead to dementia, cannot be reversed.

But boxing was Benítez’s livelihood. So the following year, he fought four times — twice in Arizona, then in Colorado and Winnipeg, Canada, jurisdictions that ignored letters from Puerto Rican authorities stating that Benítez should not be allowed back in the ring.

Benítez finally retired from boxing in 1990, the same year he filed for divorce, and moved in with his mother. Most of the millions he had earned in the ring was gone — to slot machines, promoters, hangers-on, his ex-wife. Clara blamed Gregorio for squandering Wilfred’s winnings on racehorses, although Yvonne says their father bought the horses with his own money. (The parents separated in 1994.) What remained was consumed by Wilfred’s medical care.

In 1996, Benítez attended his induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York. Later that year, he collapsed in his mother’s living room and fell into a coma. Doctors thought he would die, but Wilfred regained consciousness three days later. The violent outbursts he had afterward — throwing fits, attempting to break furniture — led his mother to commit him to a nursing home.

Ten years later, a Chicago Tribune reporter looking to chronicle the boxer’s faded fortunes found Benítez again living with his mother in her rundown two-bedroom concrete house in Carolina. Their only income was $1,100 a month in boxing pensions from the Puerto Rican government and the town of Carolina. They were too poor to repair their plumbing or pay their water and electric bills. Clara sold part of the house’s metal roof to a scrap dealer for $200 and used the money for food.

Wilfred was deep into dementia. “Where am I?” he’d ask. “What have you done with my mother? What is my name?” Compounding his medical problems, he had also been diagnosed with diabetes.

“My mother used to say, ‘What will happen if I pass away?’ ” Yvonne recalls. “I said, ‘Don’t worry, Mother. I’ll be there.’ ”

When Clara died in 2008, Yvonne kept her promise and took over as Wilfred’s full-time caregiver. That task became even more challenging in February 2017, when Wilfred had a seizure. “It was a big one,” Yvonne says. “I thought he was going to die. He grabbed my hand, begging me, ‘Help me, don’t let me go.’ ” The seizure seemed to escalate his deterioration. Eventually, his condition would rob him entirely of his ability to walk and speak.

A storm brought Wilfred Benítez back to Chicago, this time for good. On September 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico, killing nearly 3,000 people, flattening 300,000 homes, and leaving the island without electricity for months. The devastation led Luis Mateo, Benítez’s old Chicago sparring partner, to visit his ancestral home on a mercy mission that December, accompanied by Fres Oquendo, a retired local heavyweight who once fought Evander Holyfield.

Mateo had neither seen nor heard from Benítez in more than 20 years, not since El Radar’s visit to Chicago in the mid-1990s to march in the Puerto Rican Day Parade, and had no idea his old friend was sick. But when Mateo and Oquendo arrived and met up with Félix “Tito” Trinidad, another three-time titleholder from Puerto Rico, Trinidad told them Benítez had only a month to live. He took them to the house Benítez shared with Yvonne. There, Mateo and Oquendo saw the former champion curled up in bed in a fetal position.

“We both started crying,” Mateo remembers. “He had all kinds of machines on top of him. He was like dead, completely dead.”

Mateo is telling this story at Oakley Fight Club & Fitness in West Town, inside a trainer’s office decorated with fight posters and photos of boxers crouching behind gloves. The gym is right out of Fat City or Rocky. A spacious brick-walled room at the top of a flight of scuffed stairs, it contains only the elements necessary to prepare for the essentials of fighting: heavy bags, speed bags, practice rings. Boys as young as 9 are lacing up gloves to learn the sweet science.

“He was having some issues with his insurance in Puerto Rico. They were cutting down his meds,” Yvonne says. “If I would have stayed in Puerto Rico, he would already be in the grave.”

During his 62-fight career, Benítez was officially knocked out only once, in 1986 by Matthew Hilton, a Canadian who would go on to win a junior middleweight title. El Radar absorbed fewer punches than most longtime fighters, but suffered mightily from the blows that landed. Mateo wonders whether he contributed to Benítez’s condition, because he knocked him out during one of their training sessions. Mateo sees in Benítez the consequences of a career that goes on too long, the fate all fighters fear. Mateo, 62, is solid and muscular, though he speaks with the off-kilter cadence common to old fighters. He gets up at 4:30 every morning to work out, to occupy his body and brain, to keep the damage from the ring at bay. “I get scared because I see a lot of my friends who are not doing too good,” Mateo says. His advice to the young boxers he trains: “Make your money, invest in real estate, and quit.”

During his trip to Puerto Rico, Mateo realized that if Benítez was going to survive, he had to get to the mainland, where he could receive better medical care.

“What’s your goal with Wilfred?” he asked Yvonne.

“I want to take him out of Puerto Rico,” she said.

“If I bring him to Chicago, will you accept it?” asked Mateo.

Yvonne had been thinking about Philadelphia, but when she researched Chicago online, she learned that Northwestern Memorial Hospital has one of the best facilities in the nation for dementia patients. “He was having some issues with his insurance in Puerto Rico,” Yvonne says. “They were cutting down his meds. The doctor used to tell me, ‘You gotta take him out of Puerto Rico.’ If I would have stayed in Puerto Rico, he would already be in the grave.”

By June 2018, everything was in place. Mateo had returned to Chicago, found the Humboldt Park apartment for Benítez, Yvonne, and Efraín, and helped buy them tickets to fly here. Mateo, Oquendo, and Frank Velez, a Chicago Fire Department commander, carried Benítez’s wheelchair onto a commercial flight in Puerto Rico, then took him from O’Hare to the apartment. The next day, he was examined at Norwegian American Hospital, a block from his new home. Yvonne and her husband had left Puerto Rico so quickly they only had time to pack a few suitcases full of clothes.

The Uber minivan pulls in front of the greystone on Francisco Avenue. The same firefighters who carried Wilfred down the steps a few hours ago now carry him back up. His arm is stickered with Band-Aids from blood draws. Yvonne would like to buy her own minivan. She’d like to buy a house that she could wheel Wilfred in and out of, too. But there’s not enough money — hardly enough to keep up with the $1,700 a month she pays in rent. She has looked at houses in Joliet, where her daughter lives, but she hasn’t found anything affordable. They live on her pension, Wilfred’s pension, and Efraín’s Social Security benefits. Medicaid covers almost all of Wilfred’s medical bills, but there are additional costs for his care. A few years ago, Yvonne held a fundraiser with help from the Latin American Motorcycle Association. It didn’t bring in as much as she spent to organize it. John Scully, a retired light heavyweight boxer in Connecticut, sends Yvonne proceeds from the sale of boxing memorabilia: $1,000 here, $2,500 there. She uses the money to buy Wilfred food, clothing, and miscellaneous items, such as the squeeze balls that help him move his muscles.

Yvonne wheels Wilfred into the living room. It’s 5 o’clock, feeding time. Yvonne pours Osmolite, a nutrition liquid, into a plastic bag hanging from an IV pole, lifts Wilfred’s shirt, flushes out his feeding tube with water, attaches the bag, and turns on a machine that drips the Osmolite into Wilfred’s stomach. Wilfred is missing most of his top teeth, a result of diabetes, so he can eat only soft foods that Yvonne spoons into his mouth — mashed potatoes, applesauce, ice cream — something they do on special occasions. Last Christmas, Yvonne puréed him a Puerto Rican meal of pork, rice, lettuce, and tomatoes.

Yvonne and Efraín do this all themselves, seven days a week. They don’t get many visitors. Mateo stops by from time to time. An older sister from New York came in 2019, a niece from Puerto Rico in 2021. Wilfred’s ex-wife and daughter, who still live in Puerto Rico, have never been to Chicago. A fan from Alaska flew in three times. Roberto Durán promised to visit but hasn’t yet. The couple doesn’t get out much, either. Last fall, Yvonne went to the Skydeck at Willis Tower with her daughter — one of the few sights she’s seen during her five years in Chicago. And last year, Yvonne and Efraín pushed Wilfred in his wheelchair in the Puerto Rican Day Parade. Yvonne is religious, but she doesn’t go to church because that would mean leaving Wilfred’s side.

The bag of Osmolite is nearly empty. Yvonne perches on the edge of the couch, anxiously monitoring it.

“I cannot go to the bathroom because it will finish,” she says.

The machine beeps. Feeding time is over. Wilfred presses his hand against his waist, one of the few signals he can still give to his sister.

“I think he wants to go to bed, because when he does like that, he wants to have a bowel movement,” Yvonne says. Once that happens, Yvonne will have to change her brother’s diaper. She has boxes and boxes of them, stacked in a backroom of the apartment.

Wilfred smiles as Yvonne pulls off his shirt and dresses him in a hospital gown. Efraín scratches Wilfred’s bristly chin and asks in Spanish if he wants to go to bed: “Para cama, si?” Efraín hooks the lift to the sling, ratchets him out of his chair, and swings him toward the bed. When Wilfred is settled, Efraín rubs his belly and pulls a blanket over him.

“You see that?” Yvonne says. “He’s smiling. That means he’s going to bed. That means he was tired, sitting down.”

“Gracias, un beso,” Yvonne says, kissing her brother on the lips. “That’s my baby. My big baby.”

Efraín raises the head of the hospital bed so Wilfred can see a Women’s World Cup soccer match on TV. Wilfred watches with one eye open. He likes sports. Sometimes, Yvonne will put on one of Wilfred’s old fights or another boxing match.

When Wilfred could still speak, he’d comment on the action. “He used to say, ‘Oh, that’s me,’ ” Yvonne recalls. “When we used to see anybody who was going to fight that day for the first time, when they started the first round, he’d say, ‘The one in the white is gonna be the winner.’ ” When Wilfred watches boxing now, “sometimes when he sees a punch, he smiles. I don’t show his own fights a lot to him because he starts crying.”

In spite of what it has done to her brother, Yvonne refuses to condemn boxing. She and Efraín both enjoy the sport, although she attended only one of Wilfred’s fights, against Hearns in what was then the Louisiana Superdome, because “to see him boxing or one of my brothers, I feel that they are hitting me, too.”

While Wilfred watches soccer, Yvonne makes a powder of his pills with a mortar and pestle: metformin for diabetes, enalapril for blood pressure, and Seroquel, phenytoin, and Vimpat to prevent seizures. In Chicago, Wilfred gets all the medicine he needs. He hasn’t suffered a seizure in more than a year. For a while, he was able to see a physical therapist, which improved his mobility, but those visits stopped during the COVID pandemic, and now Medicaid won’t pay for them. Earlier this year, he spent a week at Northwestern Memorial when his sodium levels dropped, causing him to sleep more and move less.

Yvonne dissolves the powder in water, pours the solution into a syringe, and injects it into Wilfred’s feeding tube. It’s 8 p.m., and this is his fifth injection of the day. Yvonne will medicate him again at 11, then turn in at midnight. But even her five hours of rest belong to Wilfred. On her nightstand is a baby monitor so she can check on her brother.

“Sometimes, if he cannot sleep at night, I have to stay up with him,” Yvonne says. “He gets up and he don’t want to be alone. Sometimes, something hurts and I have to find out what it is.” Yvonne touches a finger to the bag under her right eye. “That’s why I look like this. I don’t have a deep sleep, but when I’m real tired, you can believe I’m standing with my eyes closed.”

The doctors tell Yvonne that everyone should have a sister like her. She’ll go on like this as long as Wilfred goes on. And if Wilfred outlasts her, her daughter will take over his care.

“He’s my brother, he’s my son, I’m his nurse, and I’m his doctor,” Yvonne says, wiping away a tear. “My satisfaction is I did all what I can, because he hasn’t died.”

When Wilfred Benítez’s boxing career ended, everyone who made a living off him went away: the cut men, the trainers, the agents, the promoters, the groupies, the ex-wife. But for this last fight of his life, the most important person remains in his corner.