My decades-long friendship with Bill Zehme began as a professional partnership. In the fall of 1995, after discovering that the renowned profile writer had moved back to Chicago from Los Angeles, I found his address, wrote him a letter, and mailed it with some of my very best (in retrospect, very amateurish) freelance clips. I’d been reading his work since high school, in Rolling Stone and then Esquire, and I asked if he’d meet with me to impart his writerly wisdom. To my surprise and delight, he agreed.

Not long after we linked up and hit it off, I began helping him streamline and organize transcripts for a memoir he was working on with Jay Leno. Eventually, that morphed into a gig as Bill’s first-ever research assistant — “legman” in crusty journo parlance. Over the next few years, we worked together on an homage to Frank Sinatra and a biography of the late comic-provocateur Andy Kaufman, among other collaborations. Every project was different, but with a common thread: Bill’s preternatural reportorial thoroughness. No detail was too small, no source too insignificant. Bill brought that mindset to every endeavor he undertook, but never more so than when he set forth to write a book on Johnny Carson — the culmination of a lifelong fascination with the longtime Tonight Show host.

At 15, Bill was already a full-blown Carson fanboy who holed up in his South Holland bedroom (always alone, door locked) most weekday evenings to watch, study, the undisputed lord of late night on a tiny black-and-white television — a birthday gift from his parents. “I think it was a deep, private connection,” recalls Bill’s younger sister, Betsy, who bore witness to this sacred ritual. He even named his high school newspaper column Monologue. As he’d one day write in a letter to Carson protégé David Letterman, “For me, as with so many others, [Johnny] was sort of a ‘third parent’ — that dependable happy constant presence, there no matter what.”

By 1991, as Carson entered the final year of his Tonight Show tenure, Bill had become a fast-rising star in the magazine world thanks to his stylish, funny, and intimate portraits of entertainment luminaries — Robin Williams and Madonna, Tom Hanks and Eddie Murphy, Warren Beatty and The Simpsons — in Rolling Stone. At 32, he belonged to an elite group of new New Journalists, successors to literary nonfiction OGs like Gay Talese, Tom Wolfe, and Joan Didion. He tried to land Carson back then, but it wasn’t to be. A decade would pass before Bill was finally granted a sit-down with his late-night idol.

Shortly after Carson’s death in late January 2005, Bill started work on the biography. Building on the foundation of his reporting for a 2002 Esquire profile of Carson, he began interviewing and reinterviewing friends, family members, ex-wives, costars, poker pals — anyone who had even a modestly meaningful relationships or run-ins with his subject. He also began expanding his already sizable collection of Carsonia: Anything Carson-related, he had to have.

Here’s a sampling of the jam-packed miscellany that came to fill most of a large storage locker on Chicago’s North Side: rows of fat binders stuffed with interview and show transcripts; piles of newspaper and magazine clippings; every book ever written on Carson; scads of photos; crates of videotapes, cassette tapes, and DVDs; tax returns, accounting records, and financial ledgers; marriage agreements and divorce settlements; personal notes and handwritten jokes; a canceled $1,500 check, big and pink, from Carson to his band leader, Doc Severinsen; one polyester paisley necktie, ’70s (or maybe ’80s) fugly, from the Johnny Carson Apparel clothing line. “He wanted everything we could get,” one of Bill’s more recent legmen, Layton Ehmke, recalls. “Every magic moment of Carson’s life; every aspect of the effects of those moments, in full context; every meaningful conversation and interaction, both on and off the air.”

Bill surely felt the weight of public expectation, and he fretted about doing right not only by his subject, Johnny Carson, but by the scores of people in Carson’s orbit.

But what began with such energy and enthusiasm eventually became burdensome. In early January 2007, bookmaking came to a halt. It was more than just work-related. Bill was also stymied by the suddenly unrepressed grief he had managed to keep at bay since his mother’s death. When she died only three weeks before Carson, he hadn’t allowed himself to fully process the loss, so as to stay on task with his writing and reporting. His mood was further blackened by growing consternation that was rooted in an earlier realization: Johnny Carson was no Frank Sinatra — reserved versus expressive, interior versus exterior. Which made him trickier by far to capture in prose. Several months later, Bill vented his discouragement in glum emails to Carson sources, including former Tonight Show writer Michael Barrie:

I will tell you that [Carson] vexes me in countless ways. Unlike Sinatra, he was not an exciting guy living life in big bold strokes; instead, he was — like I need to tell you — the ultimate Interior Man, large and lively only when on camera. He was the inscrutable national monument on constant full view, ever occluded nonetheless.

Before signing off, Bill also remarked that he had “somehow absorbed [Carson’s] perfectionism and inner depressed spirit, I’m fairly sure — not to mention his hiding in plain sight.” He eventually reentered the fray and charged on for six more years, all the while growing his mountain of material and tussling with self-doubt.

In general, magazine profiles are to biographies as inland lakes are to oceans: far less sprawling and easier to navigate. For Bill, Carson started as a lake and became the Pacific (or at least the Atlantic), complete with dark and unfathomable depths. Writing about his post–Tonight Show life for Esquire had been limited in scope and guided by a central clarifying theme: Johnny’s retirement. Documenting Carson’s existence from birth to earth came to feel impossible, in no small part because there was always more to be gleaned. As Bill’s friend and fellow Chicago author Robert Kurson told the Chicago Sun-Times, exaggerating slightly for effect, Bill “always felt compelled to interview a third cousin he’d just discovered, or a friend of a friend of a friend who’d emerged from his research and had a wonderful anecdote to add.” And so the mountain kept growing. “It’s mind-blowing, it’s overwhelming,” Bill said in 2016. “You can never have too much information, but in this case, yes, you can.” Nonetheless, he admitted, “There’s always this nagging thought: What if I’m missing something? That makes me nuts.”

Bill surely felt the weight of public expectation, and he fretted about doing right not only by his subject but by the scores upon scores of people in Carson’s orbit who shared memories and insights and resources. And he began questioning his own abilities, journalistic and creative, as never before. Bill was highly skilled at probing and humanizing public figures — especially talk show hosts, and perhaps most of all Letterman, whose psyche he described as “squirming, dark, and exquisite.” But Carson proved to be, in Churchillian terms, the proverbial “riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Consequently, the most important undertaking of Bill’s career became the most frustrating and intimidating.

In December 2013, eight years into his Carson toiling, Bill received a dire health diagnosis: stage 4 colorectal cancer. As a result, he became primarily focused — at first, solely focused — on surviving. With the help of major surgery, potent medication, and as much humor as he could muster, he managed to regain a semi-normal existence. But it was a very different existence from his previous one — more fraught, more tenuous, more precious — and every day was a struggle. Though he vowed to rally and continue his Carson chronicling, the mental and physical wherewithal required to do so was gone. So was his initial book advance, whittled down by debts and living expenses and health care costs. Money was a constant concern — had been for years, even before the cancer came.

“Life is a tidal wave,” Bill once said as the subject of a Loyola University alumni profile. “It’s a wave you’re caught in and the waves have just taken me where they’ve taken me.” He was talking there about his career, but it’s also true more generally. Cancer, though, was a crushing tsunami that made it far tougher to simply go with the flow. But Bill learned to do just that, partly through sheer willpower and partly by erecting psychological barriers that allowed him to cope with daily trials and indignities. He never Googled his disease, for instance. Ignorance was bliss. And, as ever, he leaned on language. In texts and emails, chemo was renamed “keemo.” He was also fond of “hot sauce” and “glow juice.” Those terms, he thought, made cancer sound “more fun.” “You better bring some levity to this,” he told Chicago in 2016. “And you better laugh every day. Because if you forget how to laugh, cancer will just spin you out.” But despite his best efforts over the course of more than nine years, it finally overtook him.

Bill’s death on March 26, 2023, at age 64, spawned a flurry of local and national obits that paid tribute to him and his unique body of work. “Mr. Zehme bridled at being identified as a celebrity biographer,” Sam Roberts wrote in the New York Times, “although most of the people he profiled had been famous long before he wrote about them. They had not, however, seemed as familiar as next-door neighbors until Mr. Zehme wrote about them.”

This project has kept me connected to a close pal with whom I can no longer communicate in any traditional sense.

Social media was also rife with remembrances. “I wish you love and godspeed old friend,” Nancy Sinatra wrote in an Instagram post. Former Chicago Tribune columnist Eric Zorn tweeted, “All Chicago writers stood in awe of Bill Zehme.”

What most of it boiled down to was this: For a long stretch of time, no one did it better. No one elevated his art form, in Bill’s case celebrity journalism (I’m cringing for him), in such an engaging and, yes, meaningful way. Of course, the same can be said (and often is said) of Carson. Even now, many would argue — including those, like Letterman and Conan O’Brien, who have done, to great acclaim, what Carson did — the King has yet to be dethroned. For resting and restless millions, including an almost-lifelong megamaven from suburban Chicago, Carson’s steadiness brought solace, his humor buoyancy, his very presence assurance that the world would keep turning — that, in Bill’s words, “tomorrow will come and we can laugh about what just happened today, and we can get up in the morning, and it’ll be alright, here we go again.”

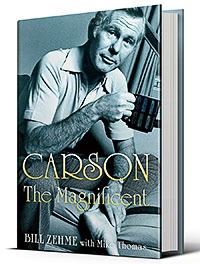

Bill completed the first three-quarters of Carson the Magnificent before his diagnosis. After his death, I was asked to finish it. Nearly 20 years in the making, the book will finally be published in early November. My part in making that possible was itself made possible by the extensive groundwork Bill laid. Everything I needed (and so much more) was there, somewhere, stashed in long-unopened binders and torn envelopes and dusty bins. It was mostly a matter of sifting through the stockpile, extracting and sorting the relevant material and reaching out to a handful of Bill’s sources, all of whom were eager to help, for further illumination. But I’ve never lost sight of the fact that, despite my contributions, this is Bill’s book.

More than just a challenging and engrossing endeavor, and more than I ever anticipated, this project has kept me connected to a close pal with whom I can no longer communicate in any traditional sense. I can’t text him about some podcast episode he’d dig, or shoot the shit with him over slabs of zesty ribs at our favorite joint, Twin Anchors in Old Town. But his influence remains ever-present, and I spent many months surrounded by artifacts from his life and career. In those ways, he’s still near. There’s also a surreal full-circle element in that, after nearly a quarter century, we’re back working together like in the old days, when Bill let a 20-something wannabe inside his rarefied world, shared knowledge, opened doors, and made me feel like I had a future in journalism. Like I could even do something akin to what he did, if maybe not how he did it. Because no one did it how he did it. Of course, I never imagined then or ever that one day he’d essentially be my legman, but here we are. A tidal wave indeed.